The concern of online abuse

In July 2022, a 23-year-old girl Zheng Linghua posted pictures of herself with her grandfather on the Chinese social media platform Xiaohongshu, sharing her joy of receiving her graduate admission letter and making her grandfather proud. However, because Zheng had her hair dyed pink in the pictures, she became the target of online abuse on various Chinese social media platforms like Xiaohongshu, Weibo, and Tiktok, receiving numerous insulting, misogynist hates where others linked her pink hair to being a slut, a whore, should not be admitted to graduate school, and so one (Lu, 2023; Yao, 2023). As a result of the online abuse, her life became miserable, and she suffered from depression; in February 2023, people learned of the tragic news that she had committed suicide (Lu, 2023).

This is only one of the incidents of online abuse in China, which often lead to tragic consequences. As we have seen on the Internet, every time they happen, the media and the public would express sympathy for the victims, indignation at the abusers, and the initiative that digital platforms should take more responsibility to prevent such harm (Yao, 2023). After Zheng passed away, users left comments under related posts on Xiaohongshu, which received thousands of likes, tagging the official account of this platform @ShuGuanJia and questioning what role the platform played in this incident, why it allowed online abuse to exist here, and if Xiaohongshu did not mean to be one of the “murderers,” they should take some actions (ChouPiWangyeah, 2023). Flew (2021) indicates that the large-scale circulation of hate speech and other forms of online abuse on digital platforms have become significant and growing issues of concern. They exacerbate hostility, discrimination, contempt and so on in society, negating the human dignity of the targeted groups, and leaving them to live in fear and harassment. Regarding this concern, whether platform companies can moderate their content for the public interest and whether it points to government involvement are crucial (Flew, 2021).

We are concerned, we speak out, and we pay attention to the platform and government; then what? We want to know, over the years, facing online abuse on Chinese digital platforms, whether there have been more actions taken and progress made. If the answer is yes, witnessing the tragedy of Zheng just happened, what can they do better? Combining academic works and relevant information, I will further study the case of Xiaohongshu, a popular Chinese social media platform with 200 million monthly active users that has grown rapidly in recent years (CBNData, 2022), governing online abuse under the guidance of the Chinese government, exploring the soundness and/or insufficiency of their specific measures.

The notice from the Cyberspace Administration of China

In China, how is the Chinese government involved in platform moderating content? There is an agency regulating, censoring, overseeing, and controlling the nationwide Internet — Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), a subordinate office under the State Council Information Office (State Council, 2014). It is responsible for Internet content management and supervising and administering law enforcement, to promote the healthy and orderly development of Internet information services (State Council, 2014). As online abuse became increasingly rampant in China, in November 2022, the agency issued a notice on effectively strengthening the governance of online abuse, stating that to target such behaviours that violate the rights of netizens and destroy the online environment, platforms should well implement the responsibility and improve the working mechanism (Secretariat of the Cyberspace Administration of China, 2022). Multiple specific requirements were put forward in this regard.

The criteria of content related to online abuse

The CAC requires platforms to establish and clarify the criteria for content related to online abuse, improve the accuracy of recognitions, and continuously improve and update the classification and criteria based on the characteristics of the platform and specific cases; they should also provide efficient reporting channels and promptly address the reported content that clearly involves online abuse (Secretariat of the Cyberspace Administration of China, 2022). On Xiaohongshu, all user-generated content needs to comply with the “Xiaohongshu Community Standards” (Xiaohongshu, 2021) effective from December 24, 2021, and users can report the comments, private messages, and posts that they believe are violations. When reporting violations, users also need to choose a category based on the “Standards,” where the one related to online abuse is “unfriendly, trolling,” corresponding to 4.1.1 “Posting content containing personal attacks and harassment of others, such as abuse, insults, deliberate trolling and harassment, etc.” in “Standards”. This item does not have further breakdowns, descriptions, or examples.

Indeed, “nearly all platforms impose their own rules, and police their sites for offending content and behaviour” (Gillespie, 2017, p. 263), and with unavoidable issues increasingly emerging on the platforms, they have to refine their rules accordingly and develop their logics underpinning how and why they intervene—it is often after they have to confront an unprepared, contentious issue (Gillespie, 2017). For example, after Zheng’s incident, there has been a surge of public attention and criticism on Chinese social media platforms regarding misogynistic hate speech and online abuse. Meanwhile, 70 per cent of the users on Xiaohongshu are female, and the platform affords a large number of feminine user-generated content (CBNData, 2022). Protecting females from misogynistic online abuse is critical for Xiaohongshu, and it is necessary to make users clear about the platform’s criteria regarding the interventions, not allowing such violations to escape by excuses. Accordingly, in the current context, Xiaohongshu should refine the “Standards,” further elaborating on the related items, which is also in line with the CAC’s requirements.

For example, In the “Facebook Community Standards” (Meta, 2023), users can click into every category to view very detailed descriptions and examples: in the “Bullying and harassment” section, among many specific actions that are not allowed, there is “Attacking someone through derogatory terms related to sexual activity (e.g. whore, slut);” a similar one is also stated in the “Hate speech” section. Based on the “Community Guidelines” of Tiktok (2023), abusive behaviours that would not be tolerated include “Content that insults another individual, or disparages an individual on the basis of attributes such as intellect, appearance, personality traits, or hygiene”, and content that promotes or supports the hateful ideology of misogyny is also incompatible with the platform. These are just a small part of the items on these two platforms, but they are clear enough to define that the large number of vicious comments towards Zheng are direct, undoubted violations. Unfortunately, for such a key and common issue, those clarifications are nowhere to be found on Xiaohongshu. In addition, the reporting logic of Xiaohongshu could also be added corresponding clearer, more targeted categories instead of using the general “unfriendly, trolling,” which may improve the efficiency of processing the numerous reports or allow the flexible adjustment of priorities of processing when necessary, such as facing some certain serious case.

The removal of violations

The CAC also requires platforms to strengthen the management of comments, promptly intercepting or removing the ones related to online abuse, violations, and illegal content, address the accounts involved in online abuse, enhance the disclosure of violations, and announce the actions taken to the public (Secretariat of the Cyberspace Administration of China, 2022). It is observed that since March 6 2023, that is, shortly after Zheng’s incident trended, the official account of Xiaohongshu has posted “The announcement of Xiaohongshu’s governance of the online abuse violations” (ShuGuanJia, 2023) every week—each one starts with stating that Xiaohongshu actively implements the requirements from CAC, resolutely cracking down on online abuse, then announces the total numbers of comments suspected of online abuse that the platform intercepts, of such comments that they removed, and of the accounts silenced or removed within the past week. It is common for platforms to remove content deemed offensive or violated, and the actions of Xiaohongshu demonstrate the platform’s decisive commitment to protecting the public, signalling its intolerance to such content or behaviours, which also helps them less associate with something offensive in the future (Gillespie, 2017) and not be penalised by CAC as being held accountable.

However, Gillespie (2017) argues that removal as a blunt instrument also comes with challenges—users who have had content or accounts removed are sometimes disgruntled, questioning the platform as subjective, hypocritical, self-interested, and biassed; especially since for large platforms, moderation cannot be complete or consistent, users are likely to believe that their removed content is unproblematic and can easily find the one they think is worse but still on the platform—who knows if the platform just removes whatever they want under the guise of protecting the community? Such scepticisms are not rare on Xiaohongshu as well, and there are constant complaints in the comment section of those announcements. I also wonder whether the only point for users to just know the total number of removals is to be informed that the platform has done some work against online abuse. What kind of posts, comments, and accounts are behind those numbers?

I believe that regarding the disclosure to the public, Xiaohongshu can take a simple, feasible step forward: for example, the weekly announcement posted by the official account can include some selected samples of the typical violations or the ones that show nuance, which is more convincing and informative. Otherwise, seeing those numbers, users’ perceptions of the threat of removal or the possibility of feeling criticised are ubiquitous but unexplained, which would discourage their active participation. Besides, in this way, users who really are potentially inclined to conduct online abuse but are not yet aware of the consequences may feel valid threats when they see specific cases of punishment. It also helps if Xiaohongshu has a public “Community Management Centre” like Weibo where all Weibo users are able to access the information of each reported content, the progress of processing, the announcement of the platform’s judgement and its rationale based on specific platform’s standards.

The protection of the targets of online abuse

The companies constructing the platforms also make design choices that impact the content and the way it is shared, wherein one of the main points that can influence the occurrence of harm is the mechanisms where recipient users engage with content, such as choosing not to engage with it—in this regard, defaults and ease of use on the platform are important (Woods & Perrin, 2021). Responsible platforms also can strengthen the protection of the targets of online abuse through specific designs, minimising their exposure to abusive messages. The CAC requires platforms to set a “one-click prevention” feature, which users can activate in an emergency when being at risk of online abuse; the function allows them to turn off private messages, comments, and shares from stranger users with one click to protect them from being abused or harassed (Secretariat of the Cyberspace Administration of China, 2022).

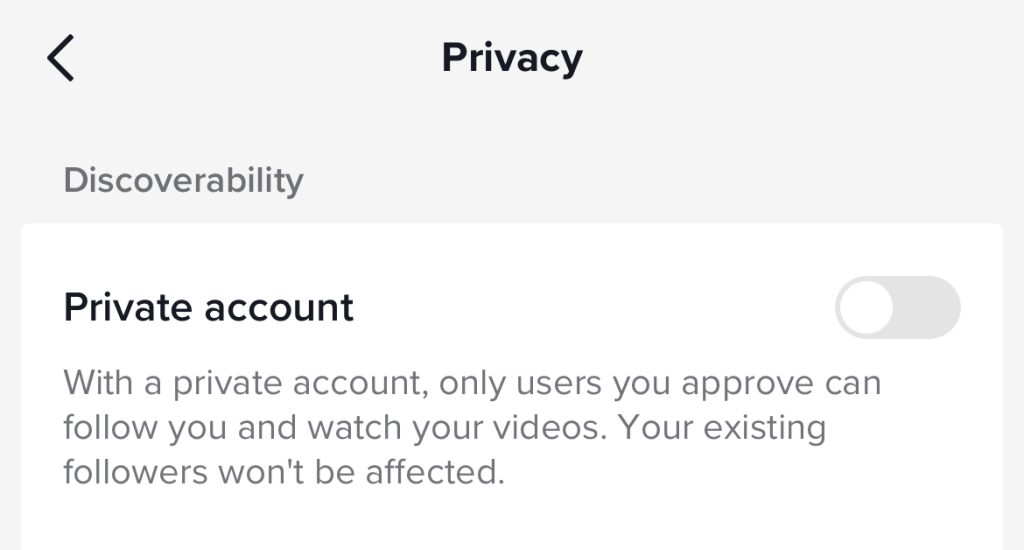

Xiaohongshu has complied with this call and set up this feature: Xiaohongshu users can turn on “one-click prevention” in the privacy settings page after four steps, and it is valid for the next seven days. Many other popular Chinese platforms like bilibili and Weibo also have this feature set. In my opinion, they can go a step further from the temporary, limited protection. For example, according to “Bullying prevention” on Tiktok (2023), the platform offers the feature of “private account”, which users can set in the account settings—if one chooses to set their account private, only people approved can follow the account and access its content, and would not be able to download any content; the accounts for individuals under 16 are set to private by default. This deeper privacy protection and abuse prevention is more powerful than the feature that needs to be reset every seven days on Xiaohongshu.

A final note

Overall, in the current online environment in China, it is imperative to make more effective efforts to govern online abuse, preventing tragedies like Zheng Linghua’s incident from happening. Studying the case of Xiaohongshu, this blog explores how this platform has taken some specific actions to crack down on online abuse following the notice from the Chinese government. However, as we see, there is still much room for progress. Platform companies should continue to develop more practical and powerful measures for the public interest based on the characteristics of the platform and typical cases rather than merely complying with the requirements in superficial ways. Learning feasible measures from other domestic or foreign platforms can also be a good way to achieve improvement.

References

CBNData. (2022). 2022 trend report on active user profiles (Xiaohongshu). Retrieved April 8, 2023, from https://www.cbndata.com/report/2891/detail?isReading=report&page=1

ChouPiWangyeah. (2023, February 20). @ShuGuanJia @GuanLiShu In this incident, may I ask what role did Xiaohongshu official play in this environment, what responsibility it took [Comment on the blog post Demand letter]. Xiaohongshu. Retrieved April 8, 2023, from http://xhslink.com/bt9DUo

Gillespie, T. (2017). Governance by and through Platforms. In J. Burgess, A. Marwick &T. Poell (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Social Media (pp. 254-278). London, England: SAGE.

Flew, T. (2021). Hate speech and online abuse. In Regulating platforms (pp. 91-96). Cambridge, MA: Polity Press.

Lu, F. (2023). ‘Pink hair prostitute’ taunts drive woman, 23, to suicide following 6 months of online abuse; millions in China mourn death. South China Morning Post. Retrieved April 8, 2023, from https://www.scmp.com/news/people-culture/trending-china/article/3210853/bullied-death-millions-chinese-mourn-after-prostitute-pink-hair-taunts-drive-woman-23-suicide

Meta. (2023). Facebook community standards. Transparency Center. Retrieved April 8, 2023, from https://transparency.fb.com/en-gb/policies/community-standards/

Secretariat of the Cyberspace Administration of China. (2022). Notice on effectively strengthening the governance of online abuse. Retrieved April 8, 2023, from http://www.cac.gov.cn/2022-11/04/c_1669204414682178.htm

ShuGuanJia (2023, April 3). The announcement of Xiaohongshu’s governance of the online abuse violations (Five). Xiaohongshu. Retrieved April 8, 2023, from http://xhslink.com/wgRNUo

State Council. (2014). Notice on the State Council empowering the Cyberspace Administration of China to be responsible for Internet information content management work. Retrieved April 8, 2023, from http://www.cac.gov.cn/2014-08/28/c_1112264158.htm

Tiktok. (2023). Bullying prevention. Retrieved April 8, 2023, from https://www.tiktok.com/safety/en/bullying-prevention/

Tiktok. (2023). Community guidelines. Retrieved April 8, 2023, from https://www.tiktok.com/community-guidelines?lang=en#31

Woods, L., & Perrin, W. (2021). Obliging platforms to accept a duty of care. In M. Moore & D. Tambini (Eds.), Regulating big tech: Policy responses to digital dominance. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197616093.003.0006

Xiaohongshu. (2021). Xiaohongshu community standards. Retrieved April 8, 2023, from https://agree.xiaohongshu.com/h5/terms/ZXXY20221213003/-1

Yao, Y. (2023). Death of pink-haired woman underlines threat from cyberbullying. China Daily. Retrieved April 8, 2023, from https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202302/21/WS63f47e6ba31057c47ebb000e.html

Be the first to comment