We often follow similar sets of procedures like this when using our phone: we download an app from app store, click on the icon, set up an account, tick on “Agree to Terms of Use”(sometimes it is a pop-up menu with Agree and Refuse button below wordy paragraphs, sometimes it kindly provide a Skip or Next button at the page corner), wait a few seconds and we are free to use the platform with our individual account.

Done. Simple and easy.

But, if we choose to read all the information, avoid all the fast path “kindly” provided by platform, what did the Terms of Use said? What right do the Privacy Police protect? What consent did we give to the platform?

Let’s take a try what we can see.

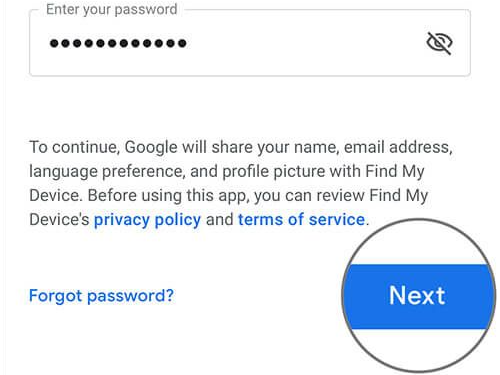

We take google as an example. After we filling in the gmail address, we could see a paragraph right below with “Next” button:

If we click on the hyperlinks and try to look into detail about Terms of Services and Privacy Policy, most of the people would be scared off by the large, complex and difficult text that can hardly to understand, not to mention those hyperlinks inserted in the text for full descriptions.

Those paragraphs and paragraphs in hyperlinks are all the data we allow Google to collect, use, and disclose. However, normally no one would waste more time on those descriptions. We click Next, and can’t wait to enjoy the services provided by the platform.

In the past decade, we watch the rise of information technology industry and the form of dominant companies in this industry that shape our life and change our world. The American-based digital platform market including Australia and many areas around the world are mostly monoplised by Big Five: Google(Alphabet), Amazon, Meta(Facebook), Microsoft, and Apple(also called GAFAM)(Van Dijk & Jose, 2020).

In this digital era, our daily life are so heavily rely on basic services provided by these platforms that the “Refuse” button would never be a choice for ordinary people. The choice of “opt-out” of data-oriented systems like digital platforms is increasingly unattainable (Marwick & Boyd, 2018).

Is free digital platforms really “free”? What are included in user privacy? Do we really well informed about the consent given to the platforms? Do we have free choices about how the data collect, use, and disclose from our account data and personal information? Where do our data go? What are the major concerns from users’ perspective? Does governance of platforms at present effectively regulate platforms from violations of privacy and issues relate to the monopoly power, or it need certain adjustment? Maybe you could find some useful answers when we take a close look at our privacy on platforms and issues when it comes to regulating digital platforms.

Are Free Platforms Really “Free”?

We have become accustomed that most of the digital platforms on our devices are free for use. It is confusing, since we only need to press download button and create an account without any monetary cost. It seems that those digital platforms provide a wide range of valuable services that already become fundamental for everyone in daily life.

The payback is invisible: platforms get huge amount of data from user account and personal information during the use of these platforms (ACCC, 2019).

From Tristan Harris (a former Google Design Ethicist, and now co-founder of the Center for Humane Technology), Netflix, documentary The Social Dilemma, 2020“ If you are not paying for the product, then you are the product.”

Digital platforms mainly focus on:

- – Engagements by the customers

- – Growth of the platform

- – Advertisement and the revenue generated

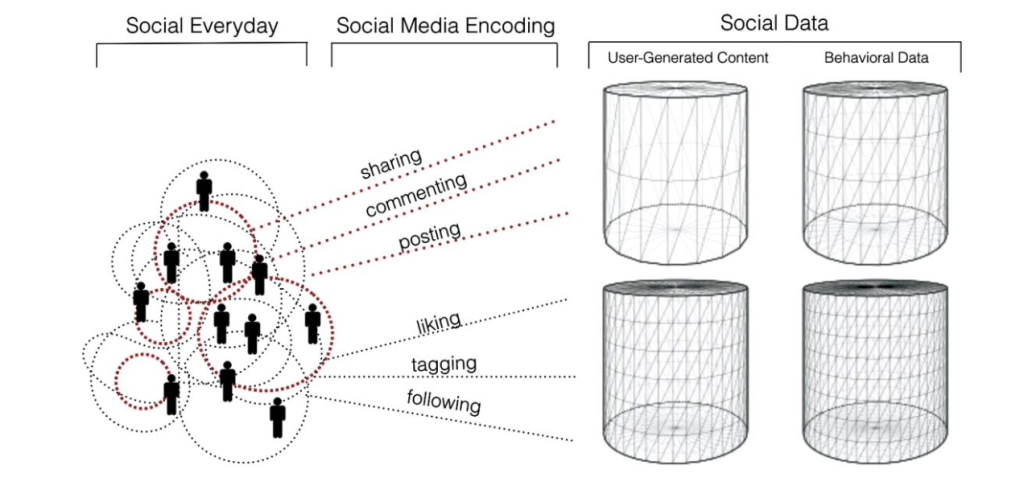

Platforms enfold people thought, behaviour, organisation and expression into the logic of big data and large-scale computation(Striphas, 2015). User participations are designed and organised by stylised activity corridors such as clicking, sharing, following, commenting and tagging, to turn those participation into standard social data which computer can understand and operate(Cristina & Kallinikos, 2017).

Based on stylised and standardised data aggregated from user participation on platforms, now it is easy to determine the success of the content. For example, it is easy to distinguish whether a brand write a successful post, or its popularity in the market. Just compare the number of likes, reposts, and comments with posts from other competitors, the answer would be clear and precise.

On the basis of this, platforms can now provide personalised content for users and other commercially oriented strategies such as targeted advertisement (Cristina & Kallinikos, 2017).

Don’t forget, platforms like Google are business companies who earn a large part of their profit from advertising business. Google, especially, its business was built around advertising from the beginning. Many small and medium companies as third-party in this information technology market heavily rely on services and target advertisements provided by those giant tech.

In addition, platforms can collect more than those user activities. Personal information such as location tracking, IP address, device identifier and other individual information are also in the collection of the data (OAIC, 2022). We could hear the lawsuits around these topics gradually more frequent than in the past few years, and we would talk deeper about this later in this article.

What is Privacy for Us?

As Nissenbaum (2009) mentioned in the book, “privacy is a messy and complex subject”. We could consider two approaches from Nissenbaum (2009) to understand privacy: access and control.

Access relate to the state that you are not “observed or disturbed by

other people”, or “being apart from other company or observation” (Nissenbaum, 2009). Other people do not have the access to “either some information about you or some experience of you” (Nissenbaum, 2009).

Control is a component or a particular form of your privacy within the scope of most scholarship, law, and policy conceptions (Nissenbaum, 2009). Therefore, you have the right to have some control over how your personal information is collected and used on digital platforms.

For users, we can apply the concept of privacy into various contexts in our life(Nissenbaum, 2009):

- – Technology platform or system

- – Business model or practice

- – A sector or industry

- – Social domain

- – Context of a relationship

Concerns of Privacy Imbalance

Do We Well Informed by Platforms?

As more and more people now are raising concerns about the privacy, data collection and data usage on platforms, we could receive many tips to limit the access from platform settings and control some of the data collection and usage that available for us.

The most frequently appeared suggestion is read privacy policies and privacy notices. The company should explain how the handle with your personal information, and provide when and why they collect the information from you(ACIC, n.d.-b).

However, think about what we found out in the story at the beginning. Many platforms’ privacy policies like the one from Google, share similar problems(ACCC, 2019):

- – Long, complex, vague

- – Difficult to navigate

- – Full of interlinked web pages

- – Use different descriptions for fundamental concepts and cause significant confusion for consumers

- – Become longer and longer after every updates

- – The tendency to understate data collection, use and disclosure

Those factors exacerbate information asymmetries between consumers and the collection of their personal information(ACCC, 2019). Google’s Privacy Policy keeps extending, and the policy updated in May 2018 increased to incredibly more than 4000 words long, with only 0.03 per cent of Australian users spent more than 10 minutes on Privacy Policy web page(ACCC, 2019).

One remarkable changes for this overhaul of Google Privacy Policy in 2018 was that, in respond to Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation(GDPR), Google rewrote the policy to be clearer, make pages easier for navigation, inserted explanatory videos, and use colourful logos and images(Charlie & Ngu, 2019). Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation is the toughest privacy and security law at present in the world, to fine against the violation of privacy and security standard in EU, no matter where the company is located in the world(GDPR, n.d.-b).

Bargaining Power of Platforms as Monopoly

The Big Five of digital company: Google, Amazon, Meta, Apple, and Microsoft are also called as “digital landload” in exaggerated extent. However, their dominance of the information technology industry is the actual steep uphill for both users and other small and medium third-party companies.

The capital and power accumulated in the past decade allowed those giant platform create their own platform ecosystems—they absorb data and turn them into nutrients, gain revenues from other third-party companies, and take over other smaller companies to expand horizontally and vertically(Van Dijk, 2020).

Such intensive competition environment dramatically rises barriers of entry for this industry, which helps those giant tech to maintain their dominance.

The design of clickwrap agreement with take-it-or-leave-it terms bundle a wide range of consent link with user privacy and personal information, which also raises platform’s bargains power and reduces from providing meaningful consents(ACCC, 2019).

Platforms such as Apple uses clickwrap agreement. On the Apple sign-up page, we can find that Apple does not have “Accept” options, as they consider users agree with their terms of use and privacy policy when users press sign-up button.

If we press “Refuse” button in the story at the beginning, we would found that we were automated return back to our phone desktop: platform do not negotiate with users about their terms of use of the data. You cannot use this platform, unless you agree with all their terms of use. This is the bargaining power of platforms.

Google’s lawsuits: Location-tracking

As the laws and regulations around online privacy and personal information in the world keep trying to follow the expansion and development of digital platforms, we can realise more combats between public authorities and giant tech companies about the violation of privacy and data security from news.

In the past five years, Google was fighting with lawsuits from all round the world.

One of the most famous lawsuit was the location-tracking issues which attorneys general say the payout is the largest-ever multistate privacy settlement and a historic win for consumers.

In November 2022, Google has agreed to a $391.5 million settlement with 40 states over allegations that Google can still track users’ location data through their devices even after they turn off the “Location History”.

For Australia, court found Google to have breached a number of statutes in the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), including sections 18, 29(1)(g), and 34, all of which relate to deceptive behavior(William, 2023).

Google did not clarify that “Location History” wasn’t the only application that was collecting and tracking users location data. The private location data is one part of the personal information that Google should provide users choice to control their data, whether to give consent to platform to collect or not. However, Google did not informed well to the users, as it misled users by leaving out crucial information regarding its settings. Location data is valuable as it provide support to the target advertising business for google. It links with users’ online activities in physical world, not only provide user preferences to advertisers, but also improves mapping services such as GoogleMap.

The Future Direction of Platform Governance on Privacy

We could see that in recent years, the amendment and new laws and regulations came out in a high speed to catch up the development and expansion of digital platforms.

We can see amendments of Privacy Act since 1988 from Australia to protect privacy under human right, new law of Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation(GDPR) from EU in 2018 to fine violation of privacy, Personal Information Protection Law(PIPC) from China to protect personal information, State Data Privacy Laws from America for legislation improvement. In Australia, Communication and Media Authority(ACMA)(2021) in 2021 also adapted News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code to amend Competition and Consumers Act in 2010.

Setting up strict laws are the common directions and effective deterrent to punish and regulate digital platforms. However, the growth of company and revenue still attract companies to violate the laws. Between 2020-2021, Google had been fined more than 180 million dollars for user privacy issues(William, 2023). The chaos led by new regulation and existing regulation model in information technology industry did not stop in the past five years.

We should always be aware that platforms are always chasing for revenue for their companies. The battlefield of privacy and human right on network would not end in the recent future.

Reference

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC). (2019). Digital Platforms Inquiry – Final Report. Canberra: ACCC. Retrieved from https://www.accc.gov.au/focus-areas/inquiries- ongoing/digital- platforms-inquiry/final-report-executive-summary

Charlie Warzel & Ash Ngu. (2019). Google’s 4000-Words Privacy Policy Is a Secret History of Internet. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/07/10/opinion/google-privacy-policy.html

Communication and Media Authority(ACMA). (2021) Treasury Laws Amendment (News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code Act 2021. Retrieved from www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2021A00021

Cristina Alaimo & Jannis Kallinikos. (2017). Computing the everyday: Social media as data platforms, The Information Society, 33:4, 175-191, DOI: 10.1080/01972243.2017.1318327

Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation. (n.d.-b). What is GDPR, the EU’s new data protection law? GDPR. https://gdpr.eu/what-is-gdpr/

Marwick, A. & boyd, d. (2019) ‘Understanding Privacy at the Margins: Introduction’, International Journal of Communication, pp. 1157-1165.

Netflix. (2020). The Social Dilemma.

Nissenbaum, H. F. (2009). Privacy in context : technology, policy, and the integrity of social life. Stanford Law Books.

Office of the Australian Information Commissioner. (2022). Privacy Act Review Report 2022. https://www.ag.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-02/privacy-act-review-report_0.pdf

Office of the Australian Information Commissioner. (n.d.-b). Online Safety. Social Media and Online Safety, Your Privacy right. https://www.oaic.gov.au/privacy/your-privacy-rights/social-media-and-online-privacy/online-safety

Striphas, T. (2015). Algorithmic culture. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 18(4-5), 395–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549415577392

Van Dijk, Jose. (2020). Seeing the forest for the trees: Visualizing platformization and its governance’, New Media and Society, DOI:10.1177/14614448209402932.

William Blesch. (2023). Google vs. Australia ACCC: What it Means for Your Privacy Practices. TermsFeed. https://www.termsfeed.com/blog/google-vs-australia-accc-privacy-practices/

Be the first to comment