Introduction: Facebook’s Role and Impact in Modern Society

As digital platforms become integral to our daily lives, Facebook has grown into the world’s largest social network. It has evolved far beyond being just an information intermediary. From news consumption and social interaction to political communication and commercial marketing, Facebook is deeply embedded in people’s everyday routines. It has significantly reshaped the way information circulates. Today, with a simple tap on a screen, information can travel across borders instantaneously, spreading with remarkable speed.

However, Facebook’s influence extends far beyond this. While many might assume social media platforms merely transmit user-generated content, Facebook has actually evolved into vast ‘platform ecosystems’. These tech giants have effectively become ‘online gatekeepers’ (van Dijck et al., 2018).

Facebook not only determines which content can be stored and disseminated, but its complex algorithms also influence information visibility through recommendations, manipulate topic prominence, and can even sway public opinion. Facebook is more than just a social platform. It acts as a centralized hub of information. It decides which content gets promoted and which gets hidden.

Digital platforms like Facebook play an important role in social governance. At the same time, they also face serious challenges in how they are managed. As van Dijck et al. (2018, p. 15) highlight, any company not central to this platform ecosystem “can hardly profit from its inherent features: global connectivity, ubiquitous accessibility, and network effects.” This suggests that Facebook not only controls global information flows but may also, to some extent, monopolize the public discourse space. Facebook has a huge number of users and strong algorithms. This gives it an unusual level of influence. But when it comes to handling data and managing content, the platform has a serious problem with transparency.

Facebook has faced ongoing criticism for many issues. These include hate speech, misinformation, cyberbullying, and extremist content. Its rules and decisions are often questioned by the public. In light of these problems, can Facebook fight hate speech just by deleting harmful posts? Does this seemingly simple solution mask deeper underlying challenges?

Background: The State of Facebook’s Governance

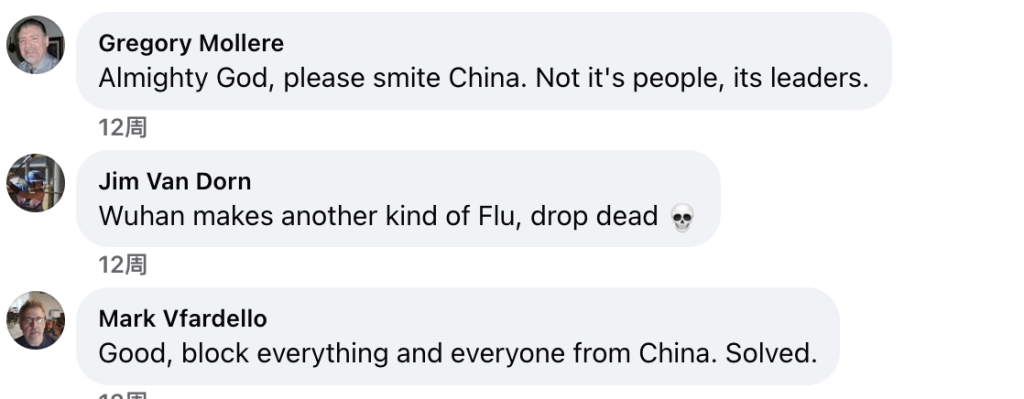

The COVID-19 pandemic, which began in early 2020, was not only a sweeping global public health crisis but also rapidly ignited a parallel ‘infodemic.’ Within this information storm, Facebook, as a core platform connecting billions worldwide, unfortunately became one of the primary breeding grounds for the generation, incubation, and viral spread of anti-Chinese and anti-Asian hate speech. During both the early and later stages of the pandemic, a large amount of harmful content appeared on Facebook. Much of this content was directed at Chinese and other Asian communities, often taking different and damaging forms.

- Stigmatization: Discriminatory terms like “China Virus” “Wuhan Flu” and “Kung Flu” were widely used. These labels wrongly linked the virus to specific countries and ethnic groups.

- Misinformation: False claims spread quickly, including accusations that the virus was a bioweapon made by China or had leaked from a lab. Other harmful content blamed the virus on Asian diets or cultural traditions.

Although Facebook relies on a combination of AI and human moderation to control hateful content, AI’s ability to recognize subtle or coded expressions remains limited, allowing significant amounts of harmful information to evade timely removal. Some users made the situation worse by using private groups or hiding hateful content in disguised formats. This allowed such content to avoid detection. The online hate speech didn’t just increase public bias against Asian communities. It also led to real-world discrimination and violence. Anti-Chinese hate speech on Facebook moved beyond the screen and had serious offline effects. During this time, hate crimes against Asians rose sharply. These included physical attacks, being refused service, and property damage. In some tragic cases, Asian families were even attacked with knives (Ellerbeck, 2020).

In the case of COVID-19-related anti-Asian hate speech on Facebook, we observed a pattern similar to the ‘Tweet and Delete’ phenomenon (Matias et al., 2015), which further complicates governance efforts. Some malicious users or groups used this strategy by posting inflammatory anti-Chinese or anti-Asian content, then quickly removing it after it gained attention. The aim is likely to avoid detection by Facebook’s systems and prevent account suspension while ensuring the harmful message spreads before removal, contaminating the information environment. This ‘Tweet and Delete’ behavior undermines governance models that rely on user reporting and post-incident moderation. By the time the platform intervenes, the original post may have vanished. This not only makes accountability difficult but also renders the platform’s deletion actions seem like merely addressing surface symptoms rather than tackling the underlying behavior. It starkly reveals the limitations of relying predominantly on ‘deletion’ as the primary governance tool. Faced with this guerilla-style propagation of hate, platforms require mechanisms that are faster, more proactive, and better equipped to predict and identify potentially malicious behavioral patterns. Otherwise, they will struggle to effectively counter this tactic.

The Role and Impact of Content Removal Policies

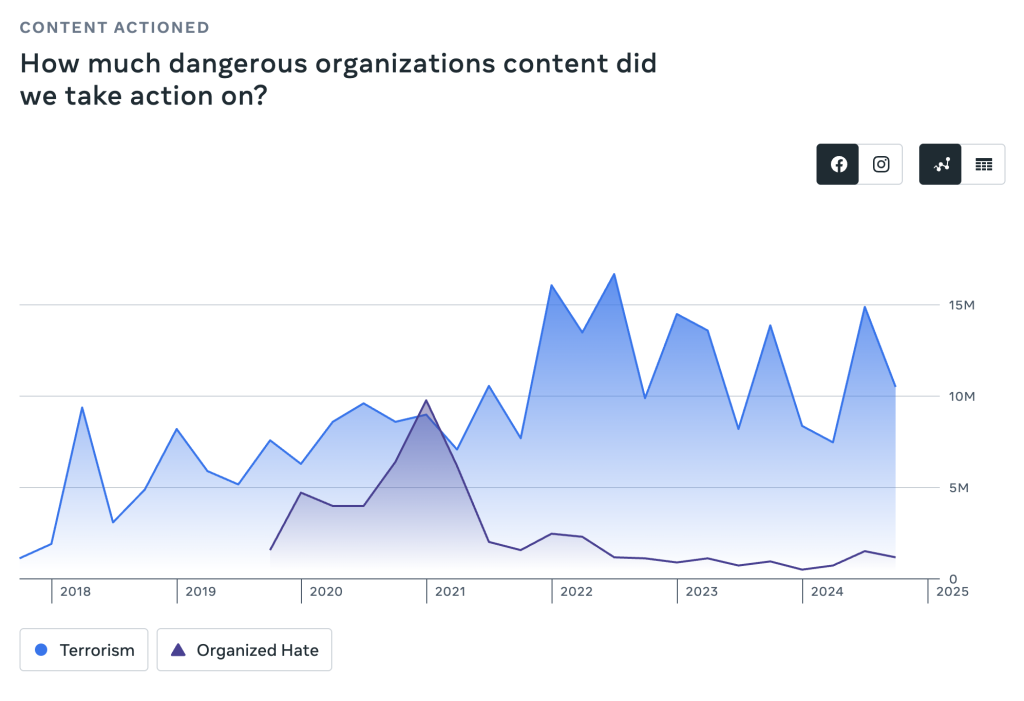

Within Facebook’s vast social network, content removal is often presented as a direct solution for tackling harmful content like hate speech. Indeed, Facebook’s transparency reports showcase staggering removal statistics, seemingly demonstrating the platform’s commitment and efficiency in its governance efforts.

Deletion often only addresses the symptoms, not the underlying issues. While removing an inciting post or shutting down a violating account deals with the immediate instance, it fails to eradicate the deeper motivations and ideologies that produce such content. As revealed by the Facebook Files disclosed by The Wall Street Journal, malicious actors are highly adaptive.

When public speech is suppressed, they quickly shift tactics, leveraging Facebook’s vast ecosystem to evade moderation:

- Moving to Private Spaces: Some extremist content migrates to Facebook’s private groups, which are shielded from public view and make oversight significantly more challenging.

- Using Coded Language: Users learn to employ techniques like ‘dog-whistling’ (e.g., substituting letters with numbers or symbols) to bypass the platform’s content detection systems.

Simultaneously, Facebook often maintains a lack of transparency regarding its governance strategies. The rationale, as suggested by Roberts (2019, p. 37-38), is that fully disclosing the specific criteria for identifying and removing hate speech could potentially be exploited by bad actors to game the system or allow competitors to replicate internal mechanisms. While this logic of secrecy may stem from commercial and security considerations, it also makes it difficult for external observers to scrutinize whether the platform enforces its rules fairly and consistently. Consequently, Facebook finds itself caught in a ‘whack-a-mole’ governance dilemma. It struggles to eradicate the roots of hate while failing to provide sufficient transparency to build user trust.

“What did we do? We built a giant machine that optimizes for engagement, whether or not it is real,”

– Presentation from the Connections Integrity team, 2019

This over-reliance on removal tends to overlook the inherent propagation dynamics within Facebook’s own ecosystem. The platform’s algorithms often favor content that evokes strong emotional responses, inadvertently amplifying inflammatory, divisive, or even extremist rhetoric by pushing it towards users. This mechanism unintentionally magnifies the reach and impact of hate speech.

Furthermore, a strategy focused solely on deletion fails to address gaps in user cognition and media literacy. Facebook boasts an enormous user base, many of whom may not accurately identify hate speech or might even participate in its spread unknowingly. If platform governance remains limited to post-hoc removal without investing in user education, enhancing transparency, fostering critical thinking, and promoting healthy public discourse, the fertile ground for hate speech persists. Malicious actors simply adapt, shifting from overt attacks on public platforms to covert planning within private groups or niche forums, thereby increasing the complexity of platform governance (Massanari, 2017). This reactive approach merely treats symptoms and cannot curb the deeper roots of the problem.

Is Facebook a ‘Public Utility’? Should We Regulate It?

Digital platforms have deeply permeated our daily lives, influencing our social interactions, consumption habits, and even how we access information. Consequently, a growing number of scholars (Flew, 2021) are debating whether these platforms should be considered ‘public utilities’ and subjected to stricter regulation. Traditional public utilities, such as water and electricity providers, typically exhibit characteristics of being foundational, monopolistic, and serving the public interest. They are generally operated by government entities or heavily regulated private institutions to ensure service accessibility, fairness, and social stability.

If applying this framework directly to Facebook presents significant challenges. While it has consolidated a quasi-monopolistic position in the social sphere through acquisitions like Instagram and WhatsApp, Facebook originated in the highly competitive internet industry. Its core driver remains a rapidly evolving business model, making it fundamentally a private, profit-maximizing enterprise.

Facebook’s influence on society extends far beyond that of a typical tech company. With algorithms that dictate what billions of people see in their News Feeds, the platform doesn’t just reflect public opinion but actively shapes it. Some perspectives are amplified while others are quietly pushed aside. At the same time, Facebook’s flaws have become increasingly difficult to ignore. As hate speech and online harassment continue to rise, the platform’s approach to content moderation and governance has drawn growing criticism. So should we be pushing for stricter regulation? It’s not a straightforward call. Leaving Facebook to police itself or relying solely on market dynamics risks allowing the company to keep prioritizing profit over public well-being, potentially sidelining user safety and mental health. But swinging too far in the other direction by treating Facebook like a public utility subject to heavy government oversight raises its challenges. It could stifle innovation, create thorny issues around international regulation and trigger legitimate concerns about free speech and state overreach.

Transparency is Key

It may seem like a quick fix to remove harmful content such as hate speech, but it’s not really a long-term solution. All we really need is a deeper rethink of how content audits work from the ground up. The most important step is transparency. Facebook should make it clear what its moderation rules are, how they’re applied and what happens when a rule is broken. Removing posts without any real explanation just leaves users confused.

Transparency isn’t only about clarity. It’s also about trust. Clear rules and consistent enforcement help users see the system as fair. This perception is key to encouraging active and meaningful participation. That matters even more on Facebook where algorithms shape what people see and don’t see. If we really want to understand how ideas move online we need clear and honest information. Otherwise it’s hard to see how platforms are influencing what we think and share. That’s a lot more effective than the vague and inconsistent approach Facebook uses now.

- This is Facebook’s current practice. When content is removed, users might see vague messages like “This page may have been removed.” “The link may be broken.” or “You do not have permission to view this.” It doesn’t have any explanation.

This lack of clarity doesn’t just confuse users about the platform’s rules. It slowly chips away at web user’s confidence in the entire system. As Pasquale pointed out in 2015 more transparency in how content is managed can also reduce the chances of online defamation and targeted attacks. A system that’s truly transparent gives users more control keeps platform power in check and helps create a safer online space. That kind of openness is especially important now when social media often traps people in fragmented information bubbles.

As one of the founding members of the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism(GIFCT), Facebook has experience publishing relevant transparency information related to combating terrorist content. The value of such transparency has been corroborated by research, showing that more transparent platforms tend to demonstrate more proactive and effective measures when dealing with specific types of harmful content (Thorley & Saltman, 2023). This practice of transparency should not be limited. Facebook need to deepen and expand it, especially in highly scrutinized areas like hate speech and misinformation.

- Publish more detailed content moderation standards and enforcement guidelines.

- Increase transparency regarding algorithmic recommendations and content ranking, while appropriately safeguarding legitimate trade secrets.

- Provide clearer, more informative notifications about enforcement actions and feedback on appeals.

By building upon existing transparency practices within its framework and committing to enhancing their depth and scope, Facebook can more effectively address public concerns about its power and move towards more responsible platform governance.

Reference

Community standards enforcement. Transparency Center. (n.d.-b). https://transparency.meta.com/reports/community-standards-enforcement/dangerous-organizations/facebook/

Ellerbeck, A. (2020, April 28). Over 30 percent of Americans have witnessed covid-19 bias against Asians, poll says. Over 30 percent of Americans have witnessed COVID-19 bias against Asians, poll says. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/over-30-americans-have-witnessed-covid-19-bias-against-asians-n1193901

Issues of Concern. (2021). In T. Flew, Regulating platforms (pp. 91–96). Polity.

Matias, J. N., Johnson, A., Boesel, W. E., Keegan, B., Friedman, J., & DeTar, C. (2015). Reporting, reviewing, and responding to harassment on Twitter. Retrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2602018(open in a new window)

Massanari, A. (2017). Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures. New Media & Society, 19(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815608807

Pasquale, F. (2015). The black box society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press

Roberts, S. T. (2019). Behind the Screen : Content Moderation in the Shadows of Social Media . Yale University Press,.https://doi.org/10.12987/9780300245318

The Facebook Whistleblower, Frances Haugen, Says She Wants to Fix the Company, Not Harm It. (2021). In Dow Jones Institutional News. Dow Jones & Company Inc.

Thorley, T. G., & Saltman, E. (2023). GIFCT Tech Trials: Combining Behavioural Signals to Surface Terrorist and Violent Extremist Content Online. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2023.2222901

van Dijck, J., Poell, T., and de Wall, M. (2018). The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Be the first to comment