Introduction

With the continuous development of the Internet, anyone can speak in the online world and pay almost nothing for their speech. With the simplification of speaking on online platforms, hate speech has exploded.

Hate speech has been defined as speech that ‘expresses, encourages, stirs up, or incites hatred against a group of individuals distinguished by a particular feature or set of features such as race, ethnicity, gender, religion, nationality, and sexual orientation (Herz & Péter Molnár, 2012).

There may be more people who are being or have been attacked by hate speech than you think in the world. The Pew Research Center mentions that 41% of Americans surveyed had experienced some form of online harassment (Vogels, 2021). The actual number will always be higher than the statistics, but why have so many people experienced hate speech?

This brings us to the issue of “freedom of speech”.

Freedom of speech was initially intended to encourage people to express different opinions and seek common ground while preserving differences. However, nowadays many people use “freedom of speech” as a get-out-of-jail-free card, constantly typing out hate speech on their keyboards to attack others.

So where is the line between hate speech and the collision of ideas? What kind of freedom of speech is acceptable, and what kind of freedom of speech is a disguise for hate speech? Should all speech suspected of being hateful be banned? While ensuring that we are not harmed by hate speech, how do we ensure our freedom of speech?

If we can understand hate speech from different perspectives and the boundaries between freedom of speech, we may be able to control the increase of hate speech while maintaining the balance between freedom of speech and legal restrictions.

Let’s think about the questions, start with understanding hate speech, and gradually lift the veil that blurs the dividing line.

The first step to governing hate speech: understanding it

How can we recognize if we are being attacked with hate speech?

If you notice that someone is using certain terms or nouns to define you, that they consider you to be inferior to others, and that they are trying to legitimize discrimination against you to disempower you (Sinpeng et al., 2021), then you can be sure that you are in the grip of hate speech.

Hate speech and public violence are often linked and can promote intimidation, discrimination, contempt, and prejudice (Flew, 2021). The more common types of hate speech are racial hate speech, gender hate speech, and LGBTQ+ hate speech etc. Some of this hate speech will appear directly, such as female politicians being harassed and verbally attacked during elections, on the X platform abusive words targeting transgender people and an increase in homophobic and racist posts, etc.

Some hate speech is closer to metaphors and symbols. For example, the OK sign is linked to right-wingers and white supremacy, and the use of numbers (13, 52, 90, etc.) reinforces racist views and discriminates against people of a certain race.

Source: USC Viterbi

Source: ADL

To reduce the capacity of people being attacked by hate speech, most online platforms are using AI to assist human reviewers in reviewing and monitoring hate speech. A large amount of posted content is screened using AI.

However, sometimes even the victims are not aware that they are being attacked by subtle hate speech, let alone artificial intelligence.

On online platforms, explicit hate speech is relatively easy for AI to identify and ban, but subtle hate speech can confuse them and make them unsure whether it needs to be dealt with. This is where human moderators come in to screen it, but they may have a chance of missing offensive content. At that time, the users who see such content need to report it to the moderation system using the report button.

Therefore, it is essential to understand what constitutes hate speech to successfully moderate it.

Different regions, different laws, different regulatory approaches

Hate speech must cause a sufficient degree of harm to its target in order to be regulated (Sinpeng et al., 2021), and insulting and offensive speech does not fully meet the standard of “harm”, which leads to a very vague scope of hate speech.

Moreover, the languages of different countries are created in their own cultures and traditions, and countries define the scope of hate speech differently, which leads to different ways of regulating hate speech.

The European Union has a fairly strict regulation of hate speech. On January 20, 2025,The Code of conduct on countering illegal hate speech online + was revised and incorporated into the framework of the DSA (European Union, 2025). The United States does not have effective laws against hate speech, and its balance undoubtedly tilts towards freedom of speech (Walker, 1995). Some Asian languages cannot directly translate the term hate speech or use it in the same legal sense as in English. As a result, there is almost no specific legislation on hate speech in the Asia-Pacific region, and compared with it, Facebook’s definition of hate speech is even more comprehensive (Sinpeng et al., 2021).

Hate speech is called “online violence” in China. Hate speech that attacks people will be censored and deleted, but invisible hate speech, such as memes, satire, and AI-generated black humor videos, is not easily regulated. In Japan, there is only relatively little legal intervention against hate speech, and it is almost impossible to clean up hate speech without relying on social opinion and people’s self-awareness.

The different legal and linguistic environments make it difficult to define hate speech, and there are still significant gaps in the regulation of hate speech worldwide.

Although online platforms have a certain number of rules against hate speech, their enforcement is not as strong as we might think. Facebook is rapidly developing its internal system for handling hate speech, but the regulatory efforts in the Asia-Pacific region still need to be strengthened (Sinpeng et al., 2021).

The gray area of freedom of speech – what is freedom and what is hate?

If you post a monkey meme on Facebook because you find it funny, that is your freedom. But if you maliciously splice a monkey meme with a human face and post it, then I’m afraid you are posting hate speech disguised as humor.

What is free speech, and what is a hate crime? The following examples will give you a quick overview of the difference.

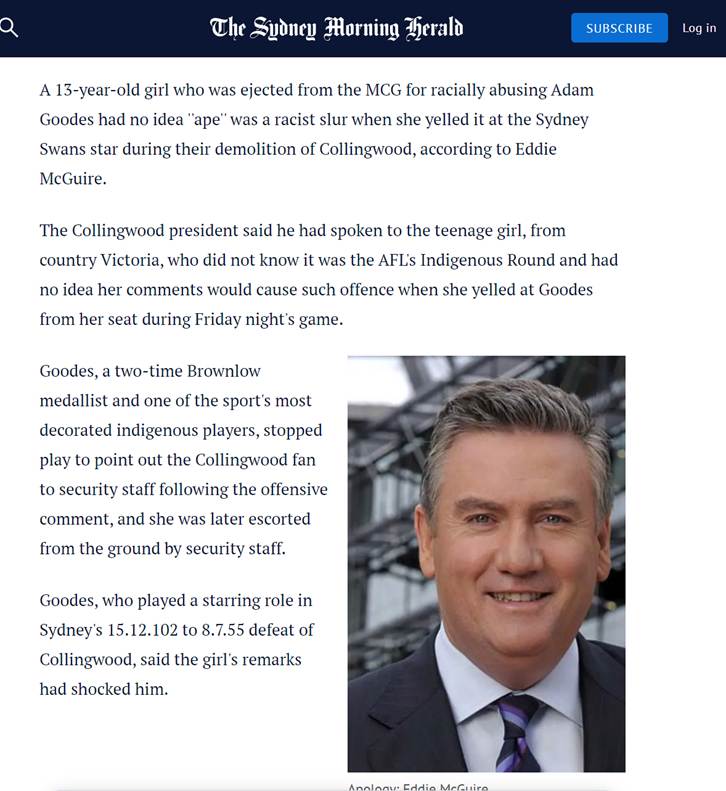

Adam Goodes, a former Australian rules football player, is also an Aboriginal. He does not tolerate any hate speech against Aborigines and has applied to have a young fan who called him an “ape” removed from the stadium, even though the fan claimed to be unaware of the racist connotations of the word.

Source: The Sydney Morning Herald

Another example is Pepe the Frog, an internet meme. Its essence is to express different emotions, but since 2015, Pepe has suddenly been used as a symbol of “alternative right-wing white nationalism” (Mihailidis & Viotty, 2017), and right-wing social media users love to associate Trump with Pepe.

In 2019, the video game Jesus Strikes Back: Judgment Day was released. The game is about killing groups of people which including feminists, minorities, and liberals. One of the characters that players can play is Pepe (Joyner, 2019).

Although the ADL has clarified that most Pepe memes are not racist (BBC, 2016), it has gone from an innocent meme to a weapon for racists to attack others. There are still people using Trump memes with Pepe’s face in 2024.

Source: Facebook

Ape, Pepe the Frog is essentially just an animal and an emotive meme, but some people have used associations and innuendo to transform it into a vehicle for hate speech. This kind of hate speech is difficult to define because users can argue that they “didn’t mean it that way”. But for the discriminated and the attacked, this metaphorical hate speech causes no less harm than direct hate speech attacks.

In addition to internet memes, hate speech can also be found in some satirical talk show. Talk show is often referred to as the “art of offense,” but where is the line between using reasonable offense to generate comedy and actual offense?

Who decides whether “offense” is a reasonable effect of the show or an entertaining expression of hate speech?

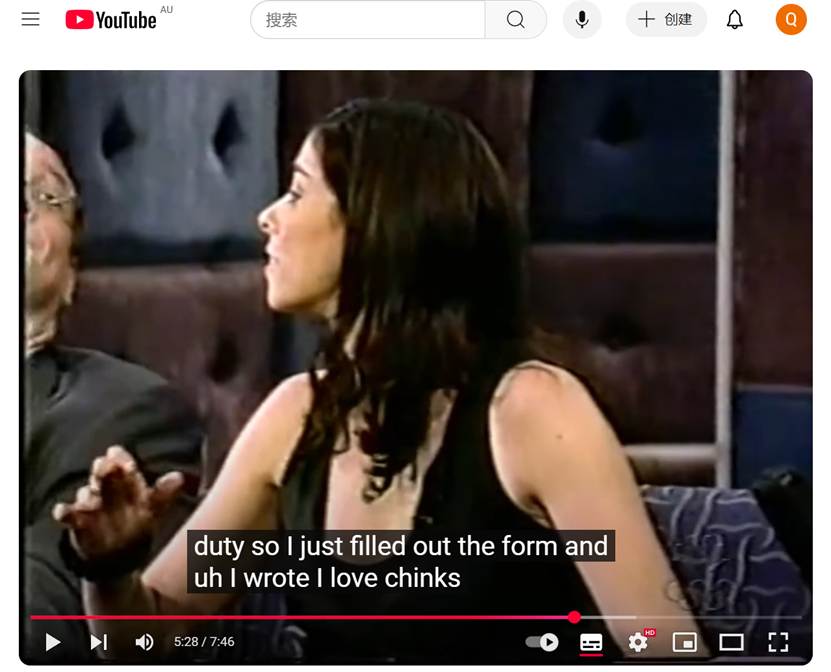

In a 2001 episode of Late Night with Conan O’Brien, comedian Sarah Silverman used the term “chink,” a well-known racial slur against Asians. While Sarah Silverman was only mocking bigotry, should talk show be more sensitive and confront so-called “jokes” when it comes to racism and other social issues? (Bootie Cosgrove-Mather, 2005)

Source: YouTube

The satire and offense of stand-up comedy indeed contain a certain artistry, but when it touches on sensitive parts, especially race, gender, and LGBTQ+, artistry cannot be used as a shield against offense, especially when the so-called “offense” is subtle discrimination and hate speech.

Standing in the gray area between freedom of speech and hate speech, people need to think carefully about the boundaries of “jokes” before speaking, rather than hurting others in the name of “freedom”.

Conflict between supervision and freedom – what can I say?

After we understand hate speech and know the relevant regulations in our region, the boundary between hate speech and freedom of speech becomes less ambiguous. This shows that we can regulate it more accurately.

But who should be responsible for regulating hate speech? Governments, platforms, or individuals?

Regulating hate speech is not a task that can be accomplished by a single person. The challenge we face is that concerns about hate speech coexist with the right to freedom of expression (Flew, 2021). To regulate it effectively, we need to unite the efforts of everyone.

Governments, platforms, and civil society organizations can collaborate on hate speech monitoring projects (Sinpeng et al., 2021), and governments can set rules that make speech more expensive. Starting in 2022, posting on all social media in China will display the IP address, which has reduced harmful speech to some extent.

Source: Weibo

The platform can guide and remind users of the content they post on the display interface. For example, TikTok Chinese version comment posting area displays the sentence “Kind words create good karma, and evil words hurt people’s hearts” to remind users not to post hate speech and encourage positive interactions between users. This ensures a healthy user community environment and reduces conflicts caused by hate speech.

Source: TikTok

Platforms can also enhance the training of platform page administrators who work for protected groups (Sinpeng et al., 2021) and combine manual review with algorithmic review to improve review accuracy.

Continuous optimization of social media algorithms to monitor hate speech is also very important.

In terms of recognition, the existing algorithms used on media platforms mainly target majority languages, and some languages cannot be recognized (Sinpeng et al., 2021). In the future, platforms should continue to optimize recognition systems to reduce missed information.

In terms of recommendations, sharing and liking on the platform affect the algorithm’s ranking of content (Matamoros-Fernández, 2017), which can result in users who don’t want to see this content being forced to view it. The platform should mark posts suspected of containing hate speech, thereby reducing their push weight.

However, over-regulation may lead to a loss of freedom of speech. How to strike the right balance is something that governments and platforms need to discuss together.

In addition, individual action is also essential.

Individual users can use the reporting function to monitor and report hate speech. When expressing personal views, pay attention to your words and attitude, respect others, and help create a positive online environment.

Individuals should also be responsible for their speech while enjoying their freedom.

Everyone is taking action, and hate speech will be effectively controlled.

Although the boundary between freedom of speech and hate speech cannot be completely clear, we still need to regulate hate speech, but not at the expense of freedom of speech.

Regulating hate speech requires the efforts of governments, platforms, and individuals. Governments formulate rules based on local culture and regulations. Platforms control the spread of hate speech by managing users and optimizing algorithms. Individuals help regulate hate speech by understanding and identifying it.

As long as everyone acts and fulfills their responsibilities, the gray areas of freedom of speech can be illuminated, and hate speech can be effectively regulated.

Reference

BBC. (2016, September 28). Pepe the Frog branded a “hate symbol.” BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-37493165

Bootie Cosgrove-Mather. (2005, November 23). The Joke’s On Us. Cbsnews.com; CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/the-jokes-on-us/

European Union. (2025). The Code of conduct on countering illegal hate speech online +. Shaping Europe’s Digital Future. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/code-conduct-countering-illegal-hate-speech-online

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating Platforms. Polity Press.

Joyner, A. (2019, June 3). Anger Over “Sick” Video Game That Allows You to Play As Trump Gunning Down Migrants, Feminists and Antifa. Newsweek. https://www.newsweek.com/anger-over-sick-video-game-that-allows-you-play-trump-gunning-down-migrants-feminists-antifa-1441745

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: the mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2017.1293130

Mihailidis, P., & Viotty, S. (2017). Spreadable Spectacle in Digital Culture: Civic Expression, Fake News, and the Role of Media Literacies in “Post-Fact” Society. American Behavioral Scientist, 61(4), 441–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764217701217

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F. R., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021). Facebook: Regulating Hate Speech in the Asia Pacific. Ses.library.usyd.edu.au. https://doi.org/10.25910/j09v-sq57

Vogels, E. (2021, January 13). The state of online harassment. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/

Be the first to comment