“Females don’t deserve to play games” – Very Toxic player on CS GO – YouTube

“Shut up and go back to the kitchen.”

On the voice channel of the game, a man shouted at the female players in the team without hesitation, his tone was full of sarcasm. She just said a tactical advice, but the result is the ridicule of the teammates. No one spoke up for her, no one reported men, and no one stopped them. This is not an “extreme example” or a niche culture in some corner. On Steam, a gaming platform with hundreds of millions of users worldwide, this happens every day. Just as others did not stop the man, this culture was acquiesced. But the question is: why has this become so common?

Platform background

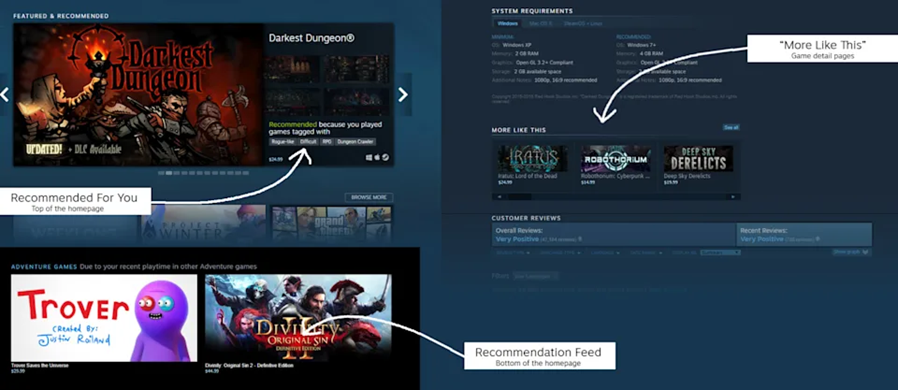

Steam is the world’s most popular open marketplace for online games, and its inherent services go beyond simply providing games. It fits into Terry Flew’s (2021) concept of new media as a global, highly engaged social network. The Steam Community is an optional social media component of Steam. It is a fully functional social media platform. Users can freely edit user profiles and create groups to interact and discuss with others. You can show anything you are interested in on your homepage. As van Dijck (2013) put it, the platform is not only a technical structure, but also a part of the “socio-technical order”, which reorganizes social relations and power dynamics, making the platform itself a producer of cultural meaning. Steam is such a typical cultural intermediary platform.

(Image 1. Steam Community Example)

Steam became a hotbed of hatred

Steam is theoretically an open, even liberal utopia – it connects players around the world, supports thousands of languages and thousands of games; But it is also in this open structure that racism, sexism, homophobia, transgender exclusion, malicious labeling, negative criticism bombardment… In the name of “entertainment”, “joking” and “free speech”, it is constantly amplified.

On this highly interactive platform, the daily behavior of these users reflects the dominant tendencies of the platform culture, rather than the contingencies of individual behavior. In a platform environment like a community, where offensive language occurs frequently and goes unchecked, it’s not just about someone saying the wrong thing. As shown in the previous video, the phrase “Go back to the kitchen” itself is a symbol, which limits women’s identity to the home and the kitchen, excluding women from appearing in the male-dominated gaming occasions, and its essence is the implicit continuation of patriarchal culture on the digital platform. In fact, this is the crushing of one culture over another, and these dominant cultures occupy the space of public expression through jokes and insults, forcing marginal cultures to constantly give way.

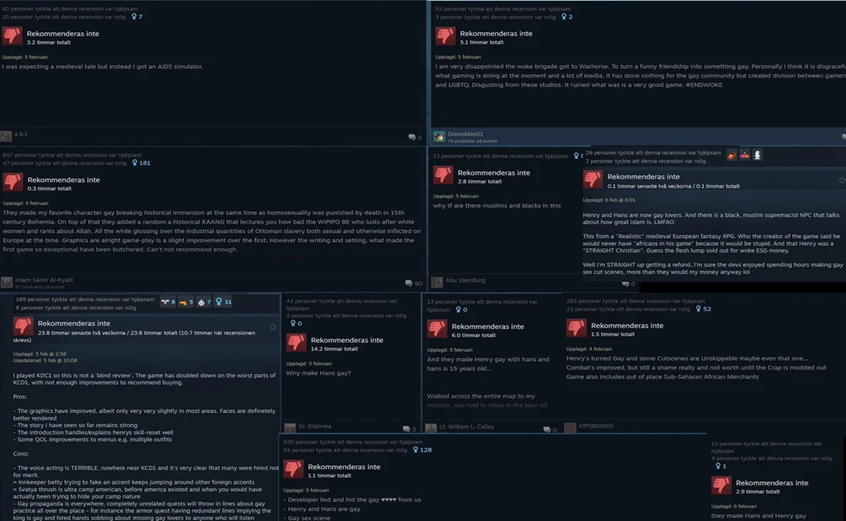

(Image 2: Hate Speech)

What this phenomenon causes is not simple offense, but a deep digital harm…

As defined by Sinpeng et al. (2021), hate speech should not be understood as merely unpleasant speech, but speech that is likely to cause harm either immediately or over time. This harm may not immediately manifest as violence, and it can offend the feelings of others while continuing to undermine the expression rights of marginalized groups at the cultural level. Female players, for example, often choose to hide their identities or even withdraw from the game space after enduring stigma and gender stereotyping, which is a silent exclusion mechanism.

Further, such verbal violence can occur in any interaction between a majority group and a minority group. Parekh (2012) pointed out that hate speech is usually a form of expression aimed at groups with specific identity characteristics (such as race, gender, religion, sexual orientation, etc.) aimed at inciting hatred.

The characteristic of hate speech is that it does not need to be violent and does not necessarily lead to direct violence; Its harm lies in its continued destruction of social identity and cultural repression of minority groups. The hate speech spread on the Steam community fits precisely into this pattern of non-explicit but structured attacks. They make discriminatory language continue to be normalized under the guise of “interaction”, “entertainment” and “satire”, and ultimately constitute the negation and expulsion of the group.

Of course, such daily attacks reflect a collective lack of user responsibility. Although most users may not agree with the offensive comments, without clear community guidance and effective feedback mechanisms, they are more likely to choose to stay silent or watch. This psychological mechanism can actually be explained by the Online Disinhibition Effect in psychology. Suler (2004) pointed out that in the network, it is easier for people to say what they dare not and will not say in real life because of the anonymous environment. At the same time, due to the lack of timely feedback, the threshold of network attack has been significantly lowered, and their awareness of consequences will be diluted accordingly. So attacks on the web don’t always stem from bad users, but from platform structures that make it extremely cheap for users to say bad things.

Overall Proliferation of Extremist and Hateful Content

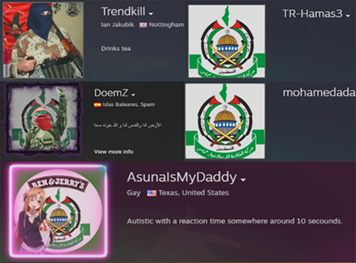

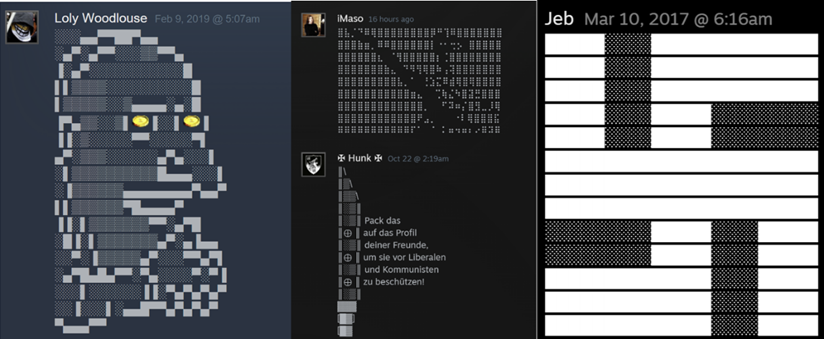

(Images 3 and 4: The Spread of Extremism)

In November 2024, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) published an in-depth study of extreme content in the Steam community, which sparked widespread discussion. ADL claims to have analyzed 1.2 billion pieces of public Steam content through machine learning tools and found more than 1.83 million of them to be extremist or hateful. These include anti-Semitic and white supremacist symbols in user profiles, accounts featuring Nazi and terrorist group logos, and text art promoting hateful ideas (Chalk, 2024).

The problem is not just that some users use Nazi symbols or set up racist groups, but that such content can persist and gain interaction in the community. This suggests that Steam’s platform structure has not only failed to suppress extremism, but has enabled it to spread in a way that is communalized and labeled. In the above extremist example, their cost of learning is almost zero, you just need to copy the text or image on your homepage, you can become one of them.

In a system devoid of mandatory regulation and guidance on the value of content, hateful content would be accepted by default as part of users’ free expression and would no longer be challenged.

As Matamoros-Fernandez (2017) points out in her research on platform racism, simple forms of expression like memes and pictures make it easier for bias to spread and harder for algorithms to see it as a problem. What’s more, the effects are not limited to the targeted. In the Toxic Speech of Tirrell (2017), it is pointed out that the reason why they are dangerous is not the level of violence on the surface, but that they wear the coat of humor and satire, are constantly repeated and imitated within the platform, and finally accepted as “part of everyday expression”. When Nazi jokes appear frequently and without consequence in the comments section, players begin to feel that these things are “okay” and even “funny,” which is the first step in “normalizing” hate culture. Ultimately, it’s not just about platforms, it’s about public culture. As Waldron (2012) put it, if a society allows the public space to be occupied by hate words, it is tantamount to acquiescing in the “denial of dignity” of some citizens. The existence of extreme content on Steam shows that the platform has not only failed to fulfill its role as guardian of the digital public sphere, but has quietly become the digital infrastructure for a culture of hate.

Images 5: The Spread of Extremism)

Push mechanism of Steam platform

If a user tends to browse and participate in communities on certain extreme topics, then he will mainly receive content from the stratosphere, which in turn reinforces his views. Gillespie (2010) argues that platforms are not neutral conduits, but rather biased amplifiers. Any engagement metric will give more controversial content more weight.

This explains why “provocative humor” is recommended more often than good-natured expressions. Under this mechanism, the platform’s algorithm will actively choose to push content to users. According to Matamoros-Fernandez(2017), platformed racism has the structural effect of amplifying specific discourse and marginalizing others, making the platform’s design, content ranking, etc., not neutral. Hate speech that is provocative and emotional is more likely to be liked and imitated, so the platform mechanism makes hate speech easier to spread than rational discussion, and more likely to attract users’ attention, thereby unconsciously contributing to the culture of hostility.

It’s worth clarifying that Steam’s recommendation algorithm itself doesn’t necessarily aim to promote extreme content; it doesn’t aim for provocative content to get attention, as some social media algorithms do. However, because Valve (Steam’s parent company) does not strictly censor content, the algorithm is blind when it comes to games and user content: as long as the content fits its model of interest, it is likely to be pushed.

(Image 6: Algorithm, Promotion Reflection)

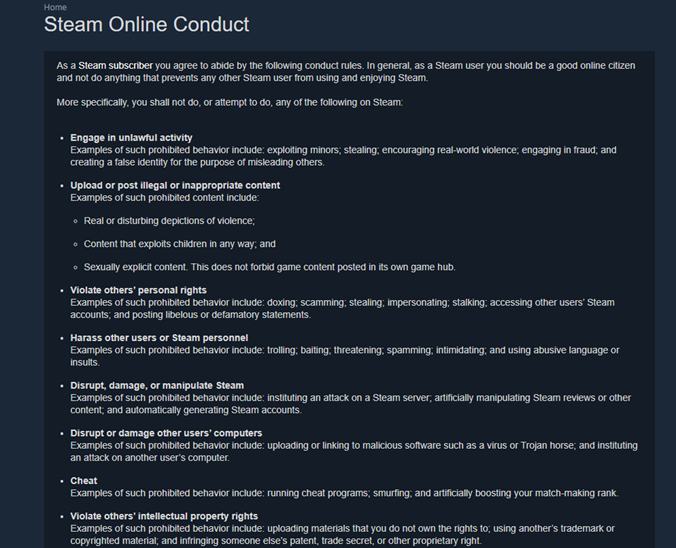

The regulatory mechanism of the platform

(Image 7: limitation)

According to official documents, Valve does not have a complete policy on hate speech, and Steam users are required to abide by the Online Code of Conduct, which prohibits harassing others and abusive behavior. Its community Content rules also clearly list the categories of content that cannot be published. Although Steam’s rules prohibit hate speech and have a mechanism for users to report it, the problem is that Steam’s apparent rules, but the lack of enforcement, hardly constitute an effective governance system.

As Sarah Roberts (2019) points out, platform governance cannot only rely on vague rules and passive reporting, but also needs clear audit processes and institutionalized support. However, Steam’s review did not specify the details of the punishment, only mentioning in general terms that Valve can suspend violators’ accounts. This opaque and inactive regulatory mechanism also makes it difficult to control hate speech on the platform.

At the same time, Steam’s multinational operating structure has further aggravated the difficulty of governance. As a platform for the global market, Steam has not set up a localized regulatory mechanism for content review according to local conditions. As Sinpeng et al. (2021) point out, the “contextual” nature of hate speech is one of its most difficult features to identify, with a comment that may be seen as satire in a US context but may constitute an explicit discriminatory attack in other countries. When the platform lacks a local language review team and a sensitive understanding of the local political culture, it is prone to misjudgment or even “invisible” phenomenon, which further weakens the ability to identify and respond to hate speech.

Methods for handling on other platforms

Take PlayStation for example. SONY has a very strict code of conduct in its player community that explicitly prohibits all forms of harassment, discrimination, threats of violence, and inflammatory speech. After reporting, users usually receive official feedback within 48 hours, and violators may face a ban, temporary ban or even permanent ban.

Microsoft’s Xbox has also rolled out a more detailed “code of safe conduct” in recent years, using both human moderation and automated detection systems to block potentially hateful content in the first place. They even set up an annual Player Safety Report to publicly explain the breach data.

Steam, by contrast, has always lacked this kind of transparency. The reporting system is extremely slow, and the platform hardly publishes any data reports on the handling of violations. To make matters worse, Steam has taken a decentralized approach to content moderation, leaving most of their community management in the hands of developers or user groups. This also leaves the content of hate speech undisturbed for a long time.

Conclusion

Steam is not the only platform where hate speech is rampant, nor is it the source of the problem. But its “non-governance” attitude points us to a very dangerous trend: When platforms shirk their responsibilities, hatred finds a crack and takes root.

Platforms always say “we’re just neutral tools,” but we know that algorithms are biased, communities are paced, and the weak are always silent. Citron (2014) said Well that the most frightening thing about hate speech is not that it destroys anyone at once, but that it makes people no longer willing to speak out.

Tirrell (2017) also reminds us that biased “jokes” and “hijacks” are quietly changing our understanding of what “normal” is.

Can Steam really do nothing? If the platform doesn’t want to be an enforcer, it can at least be a “security designer” – optimizing recommendation logic, enhancing transparent reporting processes, and working with local communities to build protection mechanisms. This is not to punish anyone, but to remind the player that what you say can be seen and has consequences.

The moment you shut down your game, ask yourself: Is your platform a truly inclusive space? Can we still make “games” just games and not habitats for hate?

Refernce list:

Banet-Weiser, S. (2018). Empowered: Popular feminism and popular misogyny. Duke University Press.

Chalk, A. (2024, November 14). Steam accused of “normalizing hate and extremism in the gaming community” in new ADL report. PC Gamer. https://www.pcgamer.com/software/platforms/steam-accused-of-normalizing-hate-and-extremism-in-the-gaming-community-in-new-adl-report/

Citron, D. K. (2014). Hate crimes in cyberspace. Harvard University Press.

Flew, T. (2021). The end of the libertarian internet. In Regulating platforms (pp. 1–41). Polity.

Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the internet: Platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media. Yale University Press.

Marwick, A., & Lewis, R. (2017). Media manipulation and disinformation online. Data & Society Research Institute.

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: The mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930–946.

Parekh, B. (2012). Is there a case for banning hate speech? In M. Herz & P. Molnar (Eds.), The content and context of hate speech: Rethinking regulation and responses (pp. 37–56). Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, S. T. (2019). Behind the screen: Content moderation in the shadows of social media. Yale University Press.

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F. R., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021). Facebook: Regulating hate speech in the Asia Pacific. Facebook Content Policy Research on Social Media Award: Regulating Hate Speech in the Asia Pacific.

Suler, J. (2004). The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 7(3), 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1089/1094931041291295

Tirrell, L. (2017). Toxic speech: The social costs of hate speech. The Southern Journal of Philosophy, 55(S1), 161–191.

Van Dijck, J. (2013). The culture of connectivity: A critical history of social media. Oxford University Press.

Waldron, J. (2012). The harm in hate speech. Harvard University Press.

Be the first to comment