Have you ever tried to track your weight loss progress on a health-tracking app, only to find weight-loss advertisements flooding your social media platform feed the next day? Tech companies have made your health information a precision marketing chip—and that is just the tip of the iceberg.

In recent years, data breaches have become a significant issue. Over the past decade, the global number of breaches has nearly tripled, compromising a shocking 2.6 billion records over the course of two years. In the US, data breaches increased by over 20% compared to any previous year within the first nine months of 2023. Besides, the threat of ransomware has grown alarmingly, with more attacks occurring in the first three quarters of 2023 than the entire previous year (Apple, 2023). These statistics revealed a cruel reality: both corporate and personal data are facing unprecedented threats.

With the development of technology, various types of health-tracking apps have shown up, covering everything from sleep and exercise tracking to period management, expanding even further into multiple niche fields, and shifting from smartphones to more private wearable devices such as smartwatches. While these innovations offer convenience enhancing the user experience, they also complicate the privacy risks. Did you know that your weight, exercise habits, and even your menstrual cycle could be secretly shared with third parties without your notice?

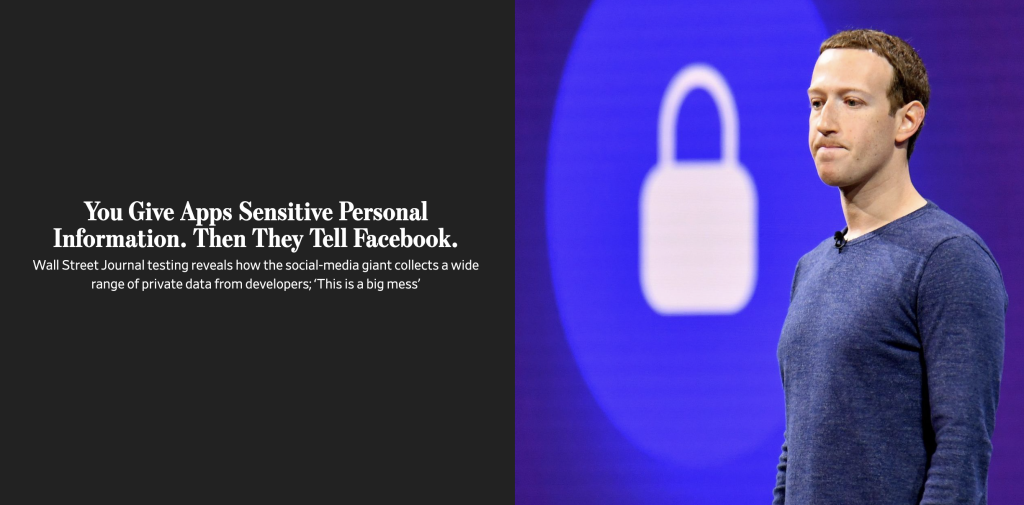

In 2019, The Wall Street Journal disclosed a piece of shocking news, i.e. Facebook was able to access large amounts of personal data through third-party health-tracking apps even if users did not actively authorise it. It mentioned Flo Health Inc., a well-known health-tracking app developer, shared user’s period information and even pregnancy attempts with Facebook without the user being explicitly told (Dow Jones & Company, 2019). Many users started to realise that the data they thought was only visible to them may have already become a commodity in the hands of Internet giants.

In this data-dominant era, is privacy protection a control or an illusion? Do we still have real control over our personal information when facing data sharing and security risks?

Definition and complexity of privacy

In the digital age, privacy is no longer just a matter of whether your data is seen, it is more about the control you have over your information. Solove (2006) argues that the key point of privacy is not simply hiding information but more about taking control of its flow. Under this framework, Marwick and boyd (2019) further suggest that privacy is not just a matter of restricting who can see the data, but is rather a social strategy, where individuals can trade off between disclosing, hiding, and sharing information to adapt to the changing technological environment.

However, this dynamic control becomes complex because of the introduction of network technology, especially when designing the collection and sharing of sensitive information such as health data. Even if users actively choose to share some data, it is difficult to control how information is spread across platforms, or even to detect whether it is being resold or abused, thereby increasing privacy risks.

Special sensitivity of health data

Health data is more sensitive than ordinary personal information, which is strictly regulated by laws in various countries. For example, the Australian Privacy Law And Practice classifies health information as ‘sensitive information’ — the same categories as race, political views, and religious beliefs — which is subject to a higher level of privacy protection than other ‘personal information’ (Australian Law Reform Commission [ALRC], 2008). Moreover, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) also emphasises the importance of health data. Article 35 of GDPR clearly states that health-relating personal data may reveal the data subject’s past, present, or future physical or mental health (General Data Protection Regulation [GDPR], 2016, Recital 35). The breaches of this data can lead to identity theft, extortion, and even being used by bad actors to conduct ‘human flesh searches’ (Looi et al., 2024).

However, in the digital age, users have less and less control over their data. Tech companies and platforms not only collect and analyse this data on a large scale, but also share it with third parties or even profit from it — often without users’ full knowledge or clear understanding of how their data is being used. It’s worth noting that the complexity not only stems from users’ own choices, but is also influenced by platform rules, algorithms, and policy transparency. These factors further weaken individuals’ ability to protect their sensitive information. In addition, platform algorithms can create detailed user profiles from health data, enabling advertisers to target users more accurately — a practice that significantly increases privacy risks.

Flo Health scandal

In 2019, The Wall Street Journal exposed a major privacy scandal involving a health-tracking app owned by Flo Health Inc., Flo Period & Ovulation Tracker, currently used by more than 100 million consumers. It was revealed that Flo Health was sharing millions of users’ health data with third parties, including Facebook’s analytics division, Google’s analytics division, Google’s Fabric service, AppsFlyer, and Flurry (Federal Trade Commission, 2021a).

The gap between Flo Health’s privacy policy and what it actually does

Flo Health’s privacy policy promised users that it would not send users’ sensitive data (such as period logs, pregnancy status, symptom records, etc.) to third parties unless users explicitly authorised it (Flo Health, 2019). However, the investigation revealed that Flo Health still transferred this sensitive data to third-party platforms, including Facebook, without user consent. Although Flo Health claimed that the data is ‘depersonalised’ and ensures privacy and security, in fact, some of the information is still leaked, breaking its promise (“You Give Apps Sensitive Personal Information,” 2019). It shows that Flo Health has a serious implementation bias in terms of privacy protection.

What’s even more alarming is Flo Health transmits user health data to advertisers and data analytics companies through an ‘app event’ mechanism, but does not effectively restrict the use of them (Federal Trade Commission, 2021a). An ‘app event’ is triggered when users take certain actions, like logging their information about periods or pregnancy details. These actions can cause an app to transmit data to a third party automatically. The data can not only be utilised for precision marketing, but could also be passed further across without users’ knowledge, raising serious privacy concerns.

It unfolds a major failure of Flo Health in privacy protection. Not only is its privacy out of line with actual practices, but its data-sharing mechanisms, such as ‘app event’, make the exposure of users’ data more widespread and harder to detect.

Flo Health scandal investigation and legal consequence

Federal Trade Commission (FTC) investigated after the news report. The result showed that Flo Health had serious opacity in the data sharing issue, and even misled users to think their information was private. Flo Health and the FTC reached a settlement agreement, including:

- Flo Health MUST obtain users’ express consent before sharing users’ health data.

- Flo Health MUST instruct all third parties who obtain health data from it to destroy the relevant information within 30 days.

- Flo Health is prohibited from making any false or misleading statements in the data collection, usage, and sharing stages (Federal Trade Commission, 2021b).

How platforms hold legal power while users are left with little choice

At the same time, Suzor (2019) pointed out in A Taxonomy of Privacy, that social media platforms are controlled by the company behind them. Users are able to utilise them, but cannot really decide how to handle their own data. Most platforms’ user agreements state that the platform has the right to change its rules at any time, or even is able to terminate a user’s access without explanation. This governance model is closer to a ‘private governance’ than a public system, where platform companies both set the rules and enforce them, with little real choice for users.

In this situation, a privacy policy is more like a ‘take-it-or-leave-it terms’ — once you click the AGREE button, seems like signing a contract that never gets read. While tech companies keep the right to change the rules at any time, making users’ privacy choices passive and vulnerable. It means users can never choose how their data is genuinely used, and the promise of privacy rules would become invalid because of the changing of platform policy, further aggravating privacy risks.

The case of Flo Health is a classic example of the problem. Despite its privacy policy promise to protect user data, the investigation revealed that the platform continues to share sensitive information with third parties, and the way the data is used remains opaque and even contrary to users’ expectations. It not only exposes flaws in platform governance, but also further heightens public concerns about health data security.

The limitation of legal penalties

Although the FTC investigated and required Flo Health to make corrections, unfortunately, the agency did not impose fines or other substantial penalties on Flo Health. This raises an important question — if tech companies can still easily escape tough penalty when they are found to have misused user data, will such violations continue?

Even more concerning is Flo Health changed its privacy policy, but still did not provide clear enough information to ensure users can completely know where the data flows to. It proved that some tech companies may just adjust their privacy agreements, making data sharing more hidden but not improving privacy protection. Thus, even though regulators take steps, without strong Implementation and accountability mechanisms, user health data will still be at risk of abuse, which reminds us privacy protection and platform governance need to be further strengthened.

Conclusion

The Flo Health scandal exposes the harsh truth that protecting your health data is unlikely to be a priority mission for tech companies. Except for strengthening the legal framework to force change, or else ‘privacy protection’ would be no more than a marketing slogan. Under the ‘private governance’ model, even if the platform promises to safeguard users’ sensitive data, but because of the lure of commercial profit and supervision loopholes, often leads to the erosion of users’ rights.

According to the platform governance concept introduced by Flew (2021), tech companies are not only platforms for providing content, but also the owner and regulator take over rules-making and implementation. The Flo Health scandal is typical evidence of the type of governance mode.

We cannot expect tech companies to take our privacy data seriously unless laws and regulations force them to. In the future, the responsibility to protect personal data lies not only in lawmaking, but also in the transparency of the platform’s governance and the users’ active consciousness. We have to:

- Advocate for stronger legal safeguards for privacy.

- Understand how to read the privacy policy and how to proactively manage your data rights.

- Urge tech companies to assume responsibility for the flow of data, making the process transparent and controllable.

Have you got ready for control over your own health data, or do you just still believe in ‘the illusion of privacy’? The first step in protecting your privacy starts with knowing where your data goes.

Reference

Apple. (2023, December 4). Report: 2.6 billion records compromised by data breaches in past two years. Apple Newsroom. https://www.apple.com/newsroom/2023/12/report-2-point-6-billion-records-compromised-by-data-breaches-in-past-two-years/

Australian Law Reform Commission. (2008). Sensitive information. In For your information: Australian privacy law and practice (ALRC Report 108). https://www.alrc.gov.au/publication/for-your-information-australian-privacy-law-and-practice-alrc-report-108/6-the-privacy-act-some-important-definitions/sensitive-information/

European Parliament & Council. (2016). General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Official Journal of the European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32016R0679

Federal Trade Commission. (2021a, January 13). Developer of popular women’s fertility tracking app settles FTC allegations that it misled consumers about data privacy. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2021/01/developer-popular-womens-fertility-tracking-app-settles-ftc-allegations-it-misled-consumers-about

Federal Trade Commission. (2021b). In the matter of Flo Health, Inc. [Decision and order]. https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/cases/flo_health_order.pdf

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. Polity Press.

Flo Health. (2019, January 19). Privacy policy [Archived web page]. Internet Archive Wayback Machine. https://web.archive.org/web/20190119031501/https://flo.health/privacy-policy

Looi, J. C. L., Allison, S., Bastiampillai, T., Maguire, P. A., Kisely, S., & Looi, R. C. H. (2024). Mitigating the consequences of electronic health record data breaches for patients and healthcare workers. Australian Health Review, 48(1), 4–7. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH23258

Marwick, A., & boyd, d. (2019). Understanding privacy at the margins: Introduction. International Journal of Communication, 13, 1157–1165.

Solove, D. J. (2006). A taxonomy of privacy. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 154(3), 477–564. https://doi.org/10.2307/40041279

Suzor, N. P. (2019). Lawless: The secret rules that govern our digital lives. Cambridge University Press.

You give apps sensitive personal information. Then they tell Facebook. (2019). Dow Jones Institutional News. Dow Jones & Company Inc.

Be the first to comment