Last month, your job application got rejected – not by a hiring manager, but likely by an automated decision system. Last week, your dating app matched you with someone it called “the perfect match.” Were you satisfied? And just this morning, during your commute, you scrolled through dozens of TikTok videos – have you ever wondered: why this one and not another?

More and more, our lives seem like a pre-packaged, “personalised” menu – but we don’t seem to have any part in making it. If we don’t make the decisions ourselves, then who is? Why are we so willing to hand over decisions to platforms and algorithms? And if AI is “lying” to us while making those decisions, can we dismantle it?

Introduction

Algorithmic recommendations, automated content moderation, generative AI, and predictive systems… Artificial Intelligence has infiltrated every aspect of our lives, influencing the experience of the digital world and reshaping the rules of the real world. We rarely question it – accepting the terms and conditions, trusting its guesses about our preferences, allowing its takeover of what we browse in the digital world…

But what if it’s all an illusion?

This blog reveals four of the most common “lies” about AI: it’s not all-powerful, neutral, understanding, nor here to serve us. In reality, AI is shaping what we see, think and do, and is even quietly participating in the governance of the world. And if we want the future to remain in human hands, it’s time to confront these illusions and reshape our relationship with AI.

Smart? Not Really – The Myth Begins

“AI is not artificial, and not intelligent.” – Kate Crawford (2021)

To uncover the lies of AI, we must first dispel the lies about AI and rebuild a more proper understanding.

As Crawford (2021) points out, artificial intelligence is neither “artificial” nor particularly “intelligent” as we often think. AI systems rely on vast physical resources: data centres, lithium mines, and poorly paid workers. Most AI systems don’t learn independently or understand human emotions; they are trained on data to simulate intelligence – like parrots repeating commands without understanding the words. Worse, when those patterns contain errors or biases, AI replicates them without question or awareness. This is the “Clever Hans effect” – AI is just a machine that follows instructions, while we wrongly attribute to them the ability to think and be neutral. (Crawford, 2021).

So why are we so misinformed about AI? Who really benefits when we believe that AI is smarter than us?

Tech companies certainly want us to think so. The more we rely on AI, the more profit they generate. Media hype and even science fiction films also play a role in reinforcing an atmosphere of ‘AI is smarter than us’. And once these myths take hold – that AI is neutral, intelligent, and dependable – we become more willing to surrender our choices and control (Boodsy, 2023). That’s exactly what justifies the growing use of algorithmic recommendations, decision-making, and AI-driven governance.

And that’s the danger: the myth of AI doesn’t just misunderstand – it creates the conditions for AI to shape our thoughts, choices, and lives.

The Algorithm Knows You – Or Does It?

In fact, we’ve “accepted” AI into our lives for a long time. We move between digital platforms like TikTok, Netflix, and Instagram, where algorithmic recommendations shape our experience – they track our platform usage data, infer our preferences, and provide us with content they think we’ll like. We enjoy this process because we enjoy the convenience of being “understood”.

But this closeness with algorithms is a gentle illusion, one that encourages us to give up control over our digital lives without resistance.

As Andrejevic (2019) warns, our cultural experience is now governed by algorithms. They filter and sort what we see, constructing a “filter bubble” – a narrow information environment that reduces diversity, diminishes our capacity for critical judgment, and threatens the civic disposition of democratic societies.

This is not abstract threatening. Think about TikTok.

TikTok’s “For You” page seems to offer decentralised content aimed at enhancing user experience, but in reality, it serves the platform’s interests. The 2023 Forbes report notes that the TikTok platform can manually “boost” or “suppress” content to manipulate virality, often suppressing non-mainstream content and artificially creating trends (Baker-White, 2023). In 2024, the European Commission launched a formal investigation into TikTok, stating that TikTok’s algorithmic design may stimulate addictive behaviours, which also suggests that the platform may harm users when profiting from algorithmic recommendations (Brussels, 2024). Recent findings by Baumann et al. (2025) suggest that TikTok reinforces specific content within the first 200 videos of “For You”, leading to biased themes and reduced content diversity, which forms filter bubbles.

We think algorithms understand us – but they only see our data. We think they aim to enhance our experience – but they are just driven by profit, competing for our attention. Ultimately, what you see becomes what you believe, and what you don’t see becomes “non-existent” – your vision, opinions and judgements are all shaped by algorithms (Just & Latzer, 2016).

While algorithms seem to provide convenience, in many ways, they subtly and “comfortably” control us. Under the guise of personalisation, platforms shape the world we mistake for reality. The more we trust that algorithms “know us”, the easier it is to become trapped in a “Truman Show” reality, no longer exploring the world beyond what algorithms present.

Code Can’t Be Fair – And That’s the Problem

AI isn’t just manipulating our digital lives – it’s reinforcing inequality on a societal level.

Many people assume algorithms are objective and neutral, without personal emotion or biases. But in fact, algorithms are designed by humans and trained on historical datasets. Like history, code reflects and often amplifies existing inequalities.

This illusion of neutrality has real-world consequences. Perhaps you’ve heard of Amazon’s abandoned AI hiring tool, which was found to favour male applicants and amplify gender bias (BBC, 2018). And that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

In 2024, researchers at the University of Washington analysed three top Large Language Models (LLMs) and found clear bias in the automated hiring process. Across more than three million comparisons, these systems show an 85% preference for names associated with white men, while names perceived as female are selected just 11% of the time (Wilson & Caliskan, 2024). This aligns with findings from Yin et al. (2024), who identifies consistent biases in ChatGPT’s hiring recommendations.

Even more concerning is the “intersectional bias”, where discrimination against individuals – like Black men – is harder to detect when looking at gender or race alone. As Wilson and Caliskan (2024) point out, these algorithmic biases are especially hard to monitor because of the complexity of the analysis, the lack of effective regulation further makes racial and gender discrimination difficult to address.

And this problem isn’t limited to hiring. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) notes that medical AI systems perform worse when diagnosing women and people of colour due to a lack of diverse data (Yang et al., 2024). Amnesty International (2024) also reports that the risk-scoring algorithms used by France’s Social Security Agency’s National Family Allowance Fund (CNAF) give lower scores to marginalised groups, stigmatising vulnerable groups such as the poor and disabled.

Algorithmic discrimination already perpetuates social inequity, and the lie of AI’s neutrality makes this inequity harder to see, challenge or reverse. As Noble (2018) reminds us, algorithms themselves aren’t racist — but they can carry embedded racial logic that becomes automated and invisible. That’s the danger: AI makes discrimination look like data.

If we don’t remain critically aware of how algorithmic decisions are designed, and if we fail to dismantle the illusion of algorithmic neutrality, we may ultimately live in a world where technology determines who gets an offer in the future world and who gets left out.

When AI Becomes Power, Not a Tool

Of all the lies about Artificial Intelligence, perhaps the most dangerous is the belief that AI is “just a tool.” Even if we realise it’s capital-driven and potentially biased, we often assume its job is to help us complete tasks and improve efficiency.

But AI doesn’t just assist us. It also quietly defines our position in society and the rules we must follow. As Crawford (2021) argues, AI is a “political cartography” – a system that defines, filters, and recreates the world, resetting the distribution of value and reshaping human cognition.

Take content moderation for example. We discussed how algorithms shape our personal experiences in the first section, but on a larger scale, AI governs the global digital public sphere. Opaque moderation algorithms can suppress certain political views, controversial labels, or sensitive topics (Pasquale, 2015). German public broadcasters have accused TikTok of “shadow banning” posts containing terms related to Nazism or LGBTQ+ culture, allowing users to publish them but preventing others from seeing them (Walsh, 2022). Dorn et al. (2024) also find that sexual minorities are less active on digital platforms because their language is misclassified as harmful.

But who decides what’s harmful?

AI builds barriers in the name of protection, thereby isolating some views from mainstream consciousness and marginalising some groups. So we must consider: who does AI serve and who does it rule?

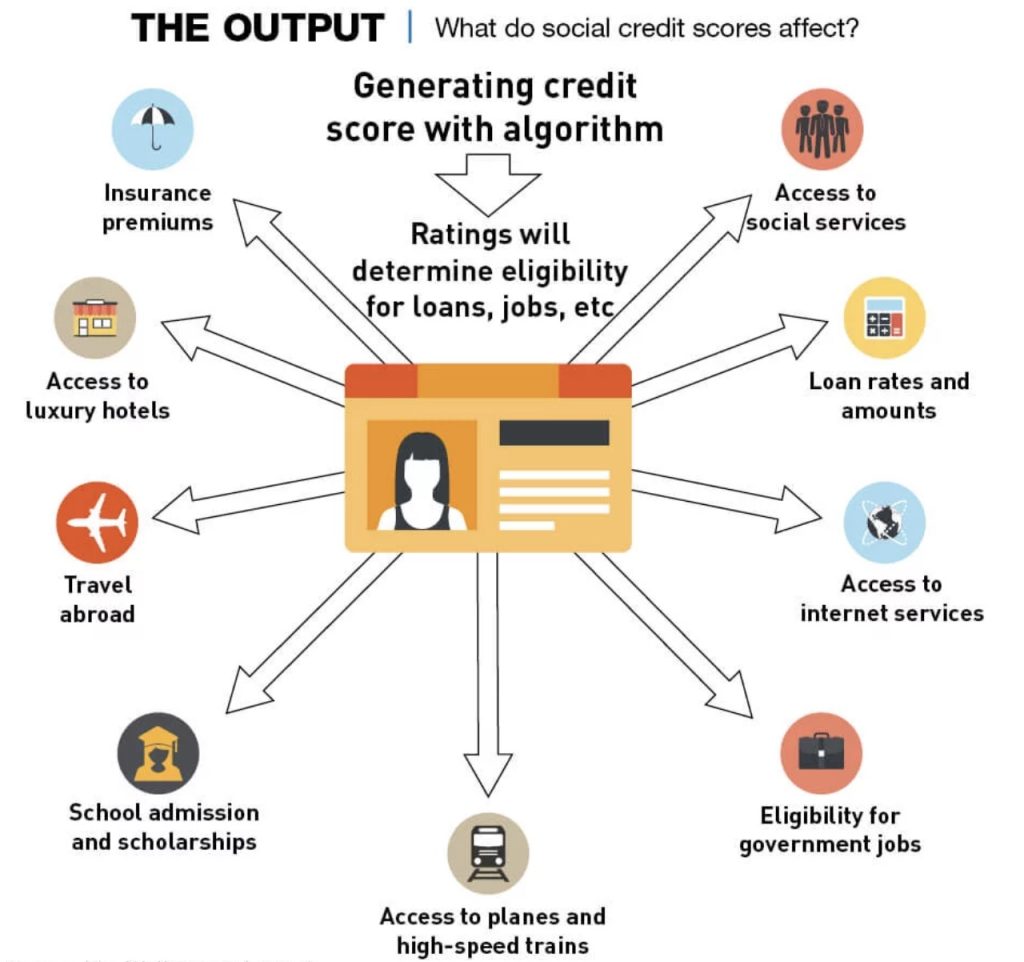

Beyond platforms, AI is reshaping rules in the real world. In China, the Zhima Credit system calculates scores for citizens based on their spending habits, credit history, and even online comments. This score affects an individual’s access to tickets, travel, rent, and loans: high scores unlock privileges, while low scores limit opportunities (Kostka, 2019). Here, This isn’t just assessment – it’s automated governance, influencing individuals’ opportunities. However, given the biases of algorithms, how can we trust such a system to make fair rules or equitably distribute power?

These examples show that AI has moved beyond the role of a neutral tool – it has become a central player in shaping social power structures. As Just and Latzer (2016) remind us – algorithms don’t just represent reality, they construct it. They determine what becomes visible, how resources are distributed, and subtly reinforce hierarchies and surveillance.

So we must realise that AI is deeply embedded in economic, political and environmental power systems, creating new hierarchies in every aspect. If we fail to recognise the nature of AI, we’ll find ourselves in a world dominated by algorithms – designed for the few, but ruling the many.

Seeing Through the Lie, and Taking Back Control

The lies of artificial intelligence are not just about “misunderstanding”, it’s also about “misinformation”.

We’ve been told to believe that AI is intelligent, neutral and can assist humans. But as we mentioned earlier, AI often redefines the distribution of power and social rules based on biased datasets.

This isn’t a technological issue — it’s a problem of power (Wanless, 2019).

AI’s lies are so deeply embedded, because too many powerful forces are invested in it: media hype, cultural fantasy, corporate promises. The public, on the other hand, is left out of the system, with no right to know, no right to monitor, and no right to choose (Boodsy, 2023). If we continue to believe the lies of AI, we will continue to hand over our voice and autonomy to opaque “black boxes”.

So what can we do?

Algorithms collect user data from every corner of people lives, but never explain how it’s used or who is accountable when something goes wrong (Amnesty International, 2024). That has to change. We need transparency – how data is collected, how algorithms are designed and how the system works. And these explains must align with public understanding, not hide behind unreadable terms of service. Only when we understand how these systems affect our lives can we further monitor whether they are operating ethically.

And those spreading the myths must be held accountable. As Flew (2021) argues, platform governanceneeds more than technical fixes, but needs social oversight. Tech companies must take responsibility for ethical controversies of AI development and deployment, and open themselves to public and third-party scrutiny (Akram et al., 2024). Researchers must rigorously evaluate the fairness of datasets rather than blindly trusting AI-generated outputs (Dorn et al., 2024). Governments must act in the public interest – by strengthening protections, raising public awareness, and including citizens in the rule-making process.

AI is not neutral or harmless. But it can be changed – if we are willing to dismantle the lies, demand more, and stay engaged.

The future doesn’t belong to machines. It belongs to us – if we are willing to take it back.

Reference

Akram, O., Krison Hasanaj, Kaya, A., Hamid Jahankhani, & El-Deeb, S. (2024). Unpacking the Double-Edged Sword: How Artificial Intelligence Shapes Hiring Process Through Biased HR Data. Emerald Publishing Limited EBooks, 97–119. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-83549-001-320241005

Amnesty International. (2024, October 16). France: Discriminatory algorithm used by the social security agency must be stopped. Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/10/france-discriminatory-algorithm-used-by-the-social-security-agency-must-be-stopped/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Andrejevic, M. (2019). Automated media. Routledge.

Baker-White, E. (2023). TikTok’s Secret “Heating” Button Can Make Anyone Go Viral. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/emilybaker-white/2023/01/20/tiktoks-secret-heating-button-can-make-anyone-go-viral/

Baumann, F., Arora, N., Rahwan, I., & Czaplicka, A. (2025). Dynamics of Algorithmic Content Amplification on TikTok. ArXiv.org. https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.20231

BBC. (2018, October 10). Amazon scrapped “sexist AI” tool. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-45809919

Boodsy. (2023). The Shadow Side of AI Part 2: Hallucinating Humans. Substack.com; The System Reboot. https://boodsy.substack.com/p/the-shadow-side-of-ai-part-2-hallucinations

Brussels. (2024). Commission opens formal proceedings against TikTok under the Digital Services Act. European Commission – European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_24_926

Crawford, K. (2021). Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. Yale University Press.

Dorn, R., Kezar, L., Morstatter, F., & Lerman, K. (2024). Harmful Speech Detection by Language Models Exhibits Gender-Queer Dialect Bias. In Preprint. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1145/3689904.3694704

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating Platforms. Polity Press.

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2016). Governance by algorithms: reality construction by algorithmic selection on the Internet. Media, Culture & Society, 39(2), 238–258.

Kostka, G. (2019). China’s social credit systems and public opinion: Explaining high levels of approval. New Media & Society, 21(7), 1565–1593. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819826402

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York University Press.

Pasquale, F. (2015). Black box society : the secret algorithms that control money and information. Harvard University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt13x0hch

Walsh, A. (2022, March 23). TikTok censoring LGBTQ, Nazi terms in Germany: report. Dw.com; Deutsche Welle. https://p.dw.com/p/48whO

Wanless, A. (2019). We have a problem, but it isn’t technology. Www.linkedin.com. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/we-have-problem-isnt-technology-alicia-wanless

Wilson, K., & Caliskan, A. (2024). View of Gender, Race, and Intersectional Bias in Resume Screening via Language Model Retrieval. Aaai.org. https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/AIES/article/view/31748/33915

Yang, Y., Zhang, H., Gichoya, J. W., Katabi, D., & Ghassemi, M. (2024). The limits of fair medical imaging AI in real-world generalization. Nature Medicine, Nat Med 30(2838–2848 (2024)), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03113-4

Yin, L., Alba, D., & Nicoletti, L. (2024, March 8). OpenAI’s GPT Is a Recruiter’s Dream Tool. Tests Show There’s Racial Bias. Bloomberg.com. https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2024-openai-gpt-hiring-racial-discrimination/?utm_source=website&utm_medium=share&utm_campaign=copy

Be the first to comment