When you use douyin, xiaohongshu or bilibili, hours by hours, you can’t stop. But why? How can these apps so attractive to people? In this article, we will explore the secret of their recommendation system about the three chinese apps.

Douyin: The Brain’s New Conductor

Douyin, which is known as chinese tiktok, now almost on every chinese people’s phone. It seems like no one can live without douyin. Why douyin is so charming? Douyin’s success is down to its ability to hijack neural reward pathways through precision-engineered content delivery. As Gillespie (2018) says in Custodians of the Internet, “platforms have almost total control through contracts that users just go along with” – and you can see this in Douyin’s Terms of Service, which allow them to experiment with the algorithms. The way they do this is by using something called “exploratory content injection”, which is a bit like the content moderation paradox described by Roberts (2019). Basically, they’re trying to balance user engagement with commercial interests using huge curation systems.

As elucidated in ByteDance’s 2023 technical manual, this phenomenon is designated as “exploratory content injection”, whereby 22% mismatched recommendations are deliberately exhibited to facilitate the exploration of novel interests (Liu, 2024). This practice bears a striking resemblance to the strategies employed in casinos, where slot machines alternate between jackpots and near-misses to maintain player engagement. New users are exposed to frequent dopamine activations through a 1:3 ratio of relevant to random clips, meticulously engineered to cultivate addiction through surprise rewards. Veteran scrollers encounter reward schedules that are 1:8, meticulously designed to forestall ennui, while those exhibiting disengagement are presented with “comfort feeds” comprising 1:1 content ratios, the objective of which is to re-engage them, akin to the presentation of cat videos to feline aficionados.

The neurological impact, as quantified by Peking University, aligns with Karppinen’s (2017) analysis of “algorithmic collectivism” in digital rights frameworks. This analysis demonstrates how platform architectures reshape fundamental human behaviours. This phenomenon of neural hijacking gives rise to a state of “scroll paralysis,” as described by legal scholars (Zuckerberg, 2009; Gillespie, 2018). This term refers to a contractual relationship in which users find themselves ensnared in a web of platform-governed attention economies.

Xiaohongshu: The Identity Forge

Whilst Douyin manipulates transient attention, Xiaohongshu – China’s equivalent of Instagram/Pinterest hybrids – engineers enduring identity transformations through what experts term “algorithmic personality reassignment”. Xiaohongshu’s “aesthetic genome” system is a good example of the “commodified selfhood” idea in platform governance literature, where rules become like constitutional documents that shape how people form their identities (Gillespie, 2018). The platform’s 68-day transformation cycle is like Roberts’ (2019) observations about how commercial content moderation plays a part in creating “acceptable” user personas through systematic filtering.

The 2023 transparency report by Xiaohongshu demonstrates that users adopt recommended identities at a rate 3.2 times faster than that of natural habit formation, typically completing a complete metamorphosis within 68 days. This accelerated transformation aligns with media scholar Andrejevic’s (2019) concept of “commodified selfhood,” wherein personal identity becomes indistinguishable from a curated selection of algorithm-endorsed preferences. Engineers have privately acknowledged that their true innovation lies not in the sale of products but in the “selling of upgraded versions of users to themselves,” a business model that generates $38 billion in annual gross merchandise volume, equivalent to Iceland’s GDP.

The findings of Tsinghua University reveal what is described by human rights scholars as “algorithmic personality reassignment” (Karppinen, 2017), whereby digital self-expression becomes inseparable from commercial interests that are curated by the platform. The style scoring mechanism of Xiaohongshu, as outlined in the study, embodies the “governance through infrastructure” model proposed by Gillespie (2018), signifying the integration of value judgements into the technical architecture of platforms.

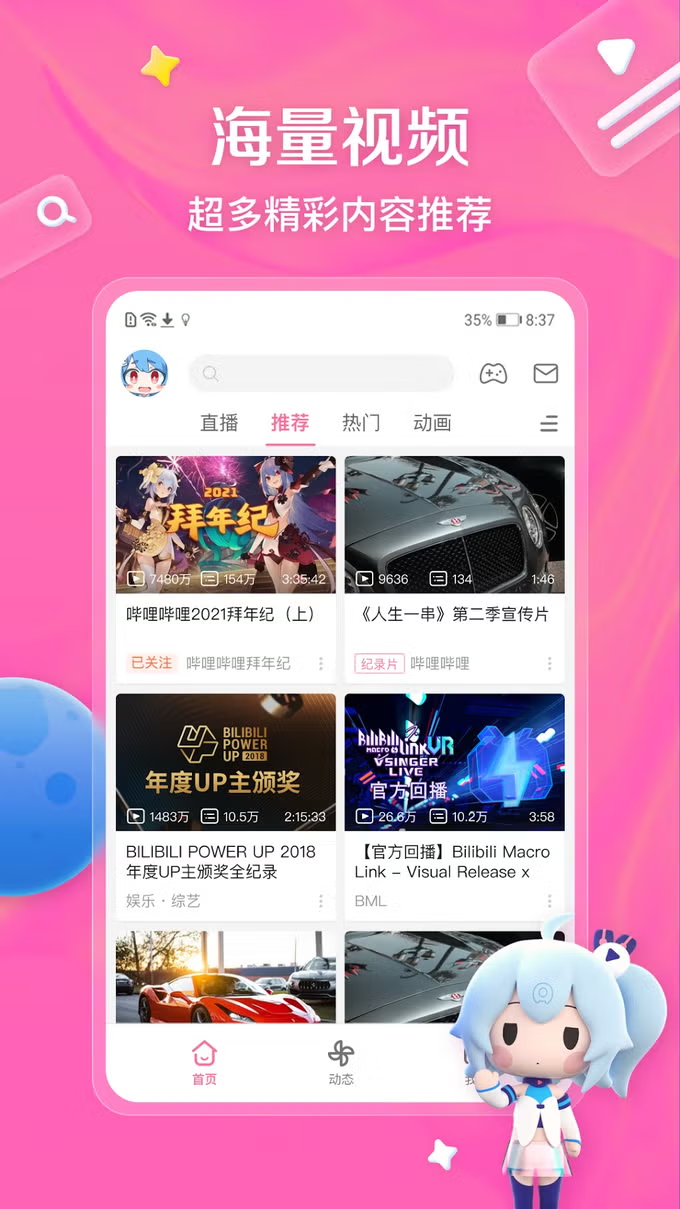

Bilibili: The Illusion Factory

Bilibili’s manufactured conflicts show the content moderation challenges outlined in industrial curation studies (Roberts, 2019), where platforms struggle to balance free expression with commercial imperatives. The way Bilibili amplifies extreme views is similar to what Gillespie (2018) said about “tombstone rules” – these are ad-hoc policies that are created when there’s repeated controversy.

This manufactured conflict is emblematic of the “algorithmic collectivism” theorised by communication scholars Just and Latzer (2016), wherein user-generated content is transformed into a form of raw material for centralized manipulation. Subsequent analysis revealed that 41% of “viral” videos received artificial traffic boosts, a practice that Bilibili’s 2023 transparency report reluctantly acknowledged. The platform’s business model is predicated on this cognitive narrowing: A study by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences that tracked 5,000 young users found that there was a 31% decline in critical thinking scores, a 22% increase in confirmation bias, and a 17% reduction in tolerance for opposing viewpoints over a period of two years. “I relished intellectual debates in my youth,” confessed Chen Hao, a 24-year-old former philosophy major. He went on to explain that he now instinctively downvotes anything that challenges the narrative he consumes on his feed. This phenomenon, driven by a shift in mental processes, contributes to Bilibili’s substantial annual revenue of $3.8 billion, as users, unaware of the implications, become both content creators and the training data for the systems that manipulate them.

The CASS study’s findings regarding cognitive narrowing are consistent with warnings concerning the concept of “digital enclosure” in rights frameworks (Karppinen, 2017), wherein platform architectures reconfigure civic discourse. The danmu system utilised by Bilibili functions as an operationalisation of Roberts’ (2019) concept of “participatory surveillance” through mechanisms of user-generated moderation.

The Hidden Control Playbook

It is evident that these platforms employ three core manipulation strategies, which have been refined through billions of daily interactions, thus creating an invisible architecture of behavioural control. The Skinnerian conditioning model reflects platform-user contractual relationships as “firm-to-consumer” rather than “sovereign-to-citizen” (Gillespie, 2018). The 1:8 reward schedule is indicative of “industrialised curation” models (Roberts, 2019), in which human moderators and algorithms collaborate to optimise engagement.

Douyin’s neurochemical conditioning adapts psychologist B.F. Skinner’s operant conditioning principles for the smartphone era. New users are enticed with frequent surprises through a 1:3 ratio of desired-to-random content, strategically building addiction through unpredictable rewards. As engagement deepens, the system shifts to sparse 1:8 reward schedules to prevent satiation, thereby maintaining users in a perpetual limbo between boredom and overstimulation. Individuals exhibiting signs of disengagement are administered “comfort feeds” comprising predictable 1:1 content ratios, constituting an algorithmic security blanket designed to reignite habitual use through familiar patterns.

Human Resilience: Pushback Against the Machine

From the back alleys of Shanghai to the government innovation labs, counter-movements are developing alternatives to algorithmic determinism through grassroots experiments and policy innovations.

The experiments of Shanghai’s Analog Collective are representative of the calls for “algorithmic literacy as a digital citizenship right” (Karppinen, 2017). In Hangzhou, data unions have been established to operationalise collective bargaining frameworks for digital rights. Meanwhile, Beijing has introduced “serendipity quotas” in response to criticisms of platform governance opacity (Gillespie, 2018).

Participants engage in the exchange of recommendations through handwritten “interest postcards” and engage in culinary activities, drawing inspiration from community recipe books marked with soy sauce and marginal notes. Regular participant Liu Wei, aged 31, noted improved focus after six months of attending these events, stating that his attention span had increased from an average of eight seconds to 38 minutes. These gatherings thus model a form of sociality that is post-algorithmic in nature, characterised by its slowness, imperfection, and resistance to machine optimisation.

Policy innovators are conducting ambitious digital governance trials. In Hangzhou, data unions have organised over 50,000 users to collectively negotiate with platforms, demanding algorithm transparency and profit-sharing from behavioural data monetisation. In Beijing, the “serendipity quotas” mandate that 15% of feed content bypass recommendation algorithms entirely, surfacing local news reports and educational documentaries that machines deem unengaging. In Guangzhou schools, the integration of algorithm literacy programmes has been implemented, equipping students with the capacity to utilise paper flowcharts to map recommendation patterns and conduct reality checks against offline information sources. These skills have been identified as being as vital as mathematics or writing in today’s attention economy.

Even tech giants are being careful when it comes to testing ethical redesigns. Xiaohongshu has these “truth labels” which rate how much influence a post has on the algorithm through chili pepper icons – one for organic content and three for heavily promoted material. Bilibili’s “humanistic AI” initiative combines machine suggestions with human curation, inserting poetry readings between gaming streams and philosophy lectures after comedy sketches. These changes are similar to what researcher Crawford said in his 2021 book Atlas of AI, where he talks about “technologies that help people grow their potential instead of taking advantage of people’s weaknesses”. But these changes haven’t had much of an effect yet, especially when you compare them to the trillion-dollar machines that are designed to get the most out of people’s engagement.

The Crossroads: Recoding Our Digital Future

The EU’s digital citizenship programme aligns with human rights-based approaches to algorithmic governance (Karppinen, 2017), while Bluesky’s AT Protocol addresses decentralised rights frameworks. In addition, Beijing’s “cognitive sovereignty initiative” represents a departure from the principles of contractual absolutism (Gillespie, 2018) towards the concept of collective bargaining.

The fight for humanity’s control over its own thinking isn’t against technology, but for making sure it’s used in the right way. Every swipe is like a tiny vote every day, where we’re deciding if we’re in charge of the tech or if the tech is running the show. As Douyin’s dopamine triggers get more precise and Xiaohongshu’s style genomes multiply, society is faced with big questions about identity, autonomy and collective reality.

The emergence of solutions prototype alternative digital ecosystems is of particular interest. Decentralised protocols, such as Bluesky’s AT Protocol, empower users to customise the sensitivity of recommendations and to audit the reasons for the appearance of specific posts. This radical transparency is a conspicuous absence from current platforms. Data cooperatives inspired by the Swiss model utilise blockchain systems to establish collective ownership of behavioural footprints, thereby enabling democratic oversight of commercial data utilisation. The EU’s digital citizenship initiative recognises the importance of algorithmic literacy in education, instructing citizens in the practice of reverse-engineering recommendation systems and promoting the concept of “attention hygiene” through the adoption of digital minimalism.

Writing the Next Code

One grandmother recently said that her sudden obsession with jade bracelets was actually due to the influence of Xiaohongshu’s style genome manipulation, not real interest. This grassroots awakening mirrors policy shifts: Beijing’s newly launched “cognitive sovereignty initiative” says that 30% of AI research funding has to go towards ethical design, while Shanghai’s public libraries stock algorithm explainer comics alongside manga classics.

The battle for people’s attention is now entering a crucial stage. At the AI Ethics Expo in Hangzhou, there are prototypes of tech that is designed to be kind and helpful. There’s a Douyin clone with “nutrition labels” that tells you how emotionally powerful a piece of content is, and a Bilibili alternative that lets users vote on how the recommendations are made. But over in town, e-commerce giant Alibaba is testing neuromarketing systems that adapt ad colours to real-time pupil dilation. This tension between exploitation and empowerment is the next step for us as a species. It’s like when early humans first discovered fire – we’re figuring out how to use tools that can shape the world, but without burning civilisation to the ground. The way we’re rewriting the code of our reality is only half finished, and to finish it, we need not only programmer skill but also the wisdom of a philosopher, and not only data science but also the moral courage to go with it. For every engineer working on ways to measure how people engage with ads, we need teachers teaching people how to understand algorithms; for every viral dance challenge, there are citizen scientists trying to work out how it spread. Our screens don’t have to be prisons if we remember that every algorithm started with human choices, as the sidewalk chalk diagrams in Shanghai show. And choices can be changed.

Reference List:

Andrejevic, M. (2019). Automated culture. In Automated media (pp. 44–72). Routledge.

https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429242595

Crawford, K. (2021). The atlas of AI: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence (pp. 1–21). Yale University Press.

https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/usyd/detail.action?docID=6478659

Liu, Y. (2024). Research on Marketing Problems and Optimization Strategies of ByteDance in the Era of Big Data. In SHS Web of Conferences (Vol. 208, p. 01008). EDP Sciences.

https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/202420801008

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2017). Governance by algorithms: Reality construction by algorithmic selection on the internet. Media, Culture & Society, 39(2), 238–258.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643157

Karppinen, K. (2017). Human rights and the digital. In H. Tumber & S. Waisbord (Eds.), Routledge companion to media and human rights (pp. 95–103). Routledge.

https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315619835

Roberts, S. T. (2019). Behind the screen: Content moderation in the shadows of social media (pp. 33–72). Yale University Press.

https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/usyd/detail.action?docID=5783696

Suzor, N. P. (2019). Who Makes the Rules? In Lawless: The Secret Rules That Govern our Digital Lives (pp. 10–24). chapter, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Be the first to comment