Introduction: When Hate Speech Becomes the New Normal

Have you ever logged into social media, excited to share something fun or interesting only to feel drained after a few minutes of scrolling? Maybe you posted an opinion and were suddenly overwhelmed by rude, aggressive replies. Perhaps you watched a friend being targeted by hateful remarks simply because of who they are. Sometimes it starts with criticism or disagreement, but it can quickly escalate into something more violent and personal.

Why is this happening so often? The internet allows everyone a voice, but it also provides a mask of anonymity. People feel free to express themselves behind screens in ways they would never do in person. According to Terry Flew (2021), common reasons people face online harassment include their appearance, race or ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and political or religious views. In some high-profile cases, online harassment has turned into widespread hate speech, illustrating how digital platforms can amplify hostility and aggression (Flew, 2021).

At the same time, the internet’s promise of free expression is complicated by inconsistent legal protection and enforcement. While most countries around the world recognise free expression, its application differs greatly. In India, Article 19(1) of the constitution guarantees citizens the right to free speech and expression, although this right is not unconditional. Section 153A of the Penal Code prohibits speech that incites animosity between religious or racial groups, illustrating the extent to which free expression can be restricted in order to preserve social harmony (Sinpeng et al., 2021). In the same line, Indonesia’s Electronic Information and Transaction Law (ITE) of 2008, amended in 2016, is frequently employed to curb the dissemination of content considered “harmful” or “negative.” However, critics argue that these restrictions often suppress dissent rather than genuinely harmful communication (Sinpeng et al., 2021).

Hate speech remains a significant problem, and obstacles to addressing it include inconsistent enforcement, political bias and unclear legal standards. A balance must be struck between preserving freedom of expression and regulating speech if the online environment is to be protected.

Switzerland “Stops Hate Speech”: How Empathy Becomes a Weapon?

In 2018, the Swiss Federation of Women’s Associations (Union F) launched the ‘Stop Hate Speech Project’ to combat online hate speech with compassion. The project encourages people to respond to hate speech with compassion and understanding and promotes respectful and constructive dialogue. This strategy is particularly important for the protection of vulnerable groups such as women and ethnic minorities.

The project is a collaboration between the S-Institute, ama-sys, the Laboratory for Digital Democracy Lab (UZH), the Public Policy Group, and the Migration Policy Laboratory (ETH). It was financed by InnoSuisse (2020-2022) and the Swiss Federal Office of Communications (BAKOM) (2021-2022). Together, these organisations hope to improve technology and research approaches for detecting and combating hate speech.

Since its inception, the project has gone through three phases. The first phase (2018-2020) focuses on data collection and civil society engagement to better understand the nature of online hate speech. The second phase (2020-2022) focuses on developing algorithms and evaluating alternative ‘counter-speech’ strategies. A non-profit organisation that collaborates with media businesses and civil society organisations to enhance and investigate public discourse on the Internet. Entering phase three (2022-2024), the scope expanded with the foundation of the non-profit Public Discourse Foundation (PDF) in 2023. This phase focuses on not only suppressing hate speech but also promoting valuable online contributions, combining research findings with practical solutions through collaboration with media firms and civil society organisations.

“Stops Hate Speech” Core Strategies

Empathetic Response

The Stop Hate Speech initiative employs empathy as a strong technique for combating online hate speech. Empathy-based approaches, rather than criticising or shaming someone, seek to inspire contemplation and raise awareness of the harm their comments can cause.

“Empathy-based counter-speech messages can increase the retrospective deletion of xenophobic hate speech by 0.2 SD and reduce the prospective creation of xenophobic hate speech over a 4-week follow-up period by 0.1 SD.” -Hangartner et al. (2021)

The study with 1,350 Twitter users found that people who got empathetic replies were 8.4% more likely to delete hateful comments. Also, their negative posts decreased in the next month (Hangartner et al., 2021).

Stop Hate Speech volunteers use this method by replying to harmful comments with empathy and understanding. The goal is to turn harmful conversations into thoughtful and kind discussions by appealing to people’s better side and letting them rethink their actions.

Technological Support

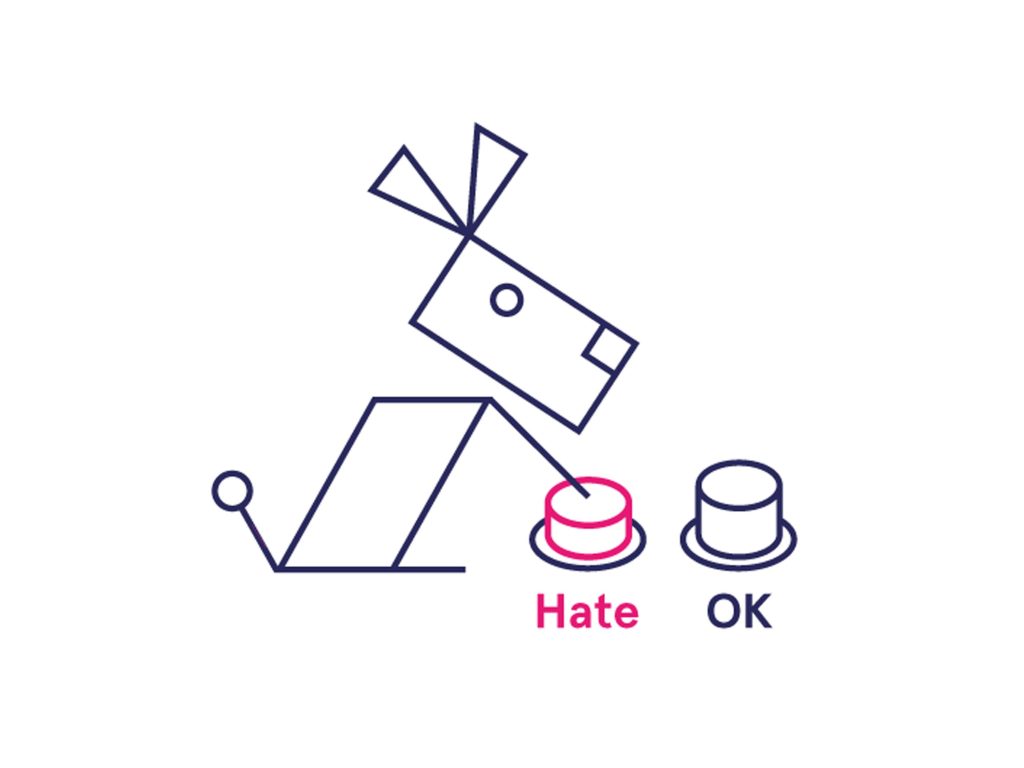

The Stop Hate Speech project uses tech tools to spot hate speech online. Its most well-known tool, Bot Dog, was developed with help from InnoSuisse, BAKOM, ETH Zurich, and others. Trained on over 420,000 labeled comments, it is one of the most accurate hate speech detectors in German-speaking areas.

Bot Dog uses NLP (natural language processing) and machine learning to check text for hate speech patterns. It relies on deep learning to pull text data, apply NLP methods, and update its model with new inputs. The system gets better by using keyword lists, sentiment checks, and human reviews.

A unique feature is Bot Dog’s fun design. It looks like a cute puppy, and users can rate comments by swiping left or right on phones or computers. This game-like method keeps users involved and makes moderating comments less boring. Sasha Rosenstein, a staff member at Alliance F, said: “We aim to calm online tensions by combining tech and public efforts.”(Deutsche Telekom AG, 2023)

Collaborative Efforts

Collaboration activities in the Stop Hate Speech initiative are centred on combining human oversight and intervention to improve the effectiveness of technical solutions. While algorithms such as Bot Dog provide automated detection, human reviewers are crucial in analysing and filtering flagged content to ensure accuracy and impartiality.

Over the last three years, Alliance F organised over 1,200 volunteers to review around 300,000 comments. This human interaction guarantees that the project’s automated systems are complemented with context-aware moderation, hence improving the algorithm’s ability to detect nuanced or context-dependent speech.

In addition, researchers from ETH Zurich and the University of Zurich help to evaluate and improve various counterspeech tactics. This continual collaboration helps to align the project’s objectives with real-world difficulties, ensuring that both technology tools and human interventions are constantly polished and enhanced.

Empathy Strategies: What Works and What Doesn’t

Why Empathy Matters

Empathy can be a powerful tool for changing minds. When people feel understood, they are more likely to think about their actions and reconsider offensive remarks.

The Science Behind Empathy

According to Khalid and Dickert (2022), empathy works by prompting moral contemplation. It involves both experiencing another person’s emotions (affective empathy) and understanding their perspective (cognitive empathy). This combination allows individuals to perceive the consequences of their behaviour, motivating them to change. Khalid and Dickert argue that empathy promotes reflection and encourages prosocial behaviour.

Faster and Friendlier Than Legal Measures

One big advantage of empathy-based strategies is speed. Unlike legal actions that can take months or even years, empathy-based responses are immediate. They happen right where the harmful comments are made, often within minutes.

This contrasts dramatically with Germany’s Network Enforcement Act (NetzDG), which mandates that social media networks remove “manifestly unlawful” content within 24 hours and all illegal content within 7 days. According to Tworek (2019), NetzDG establishes clear deadlines, but enforcing them can be difficult and time-consuming. Platforms must determine the legality of reported content, which frequently requires legal expertise and advice. Furthermore, platforms are expected to publish transparency reports outlining how they handle complaints, which can further prolong the process. Tworek (2019) emphasises that these requirements, despite their well-meaning, can render the process ineffective and time-consuming in terms of delivering timely assistance.

Empathy-based tactics are less confrontational. They prioritise discussion and understanding over punishment. This makes them more acceptable to the public and less likely to elicit a backlash.

The Limitations of Empathy

Empathy-based methods for fighting hate speech have real challenges. How well these approaches work depends a lot on the responder’s skills, awareness, and emotional state. This makes empathy-based interventions unpredictable and hard to measure. Khalid and Dickert (2022) explain that empathy involves both feeling someone else’s emotions (affective empathy) and understanding their perspective (cognitive empathy). But not everyone is equally skilled at empathy, and even the same person’s ability to respond can change based on things like stress, fatigue, or emotional distress. Because of these differences, empathy-based methods often feel inconsistent and hard to evaluate.

Social media platforms make things worse. Sites like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube thrive on user engagement, and their algorithms are built to amplify content that grabs attention. Unfortunately, anger, conflict, and controversy attract far more clicks and reactions than kindness or understanding. When algorithms prioritize sensational or divisive content, empathy-based strategies struggle to create calm, thoughtful conversations in an environment designed for conflict.

The deeper problem is that empathetic response alone cannot solve deeper social problems such as racism, misogyny or political polarisation. While empathy can stimulate reflection, it cannot solve prejudice, and while empathy can change a person’s mindset, it cannot change the structured social conflicts that arise because of prejudice. In the face of these problems, empathy is far from adequate as a solution.

The Path Forward: Empathy, Technology, and Policy

Making Technology Work for Kindness

Technology can do more than just block bad content; it may also foster empathy. For example, AI technologies can now recognise remarks like “This remark may hurt the disabled community,” replacing strict censorship with polite cautions that persuade users to examine their words before sending them.

Advanced algorithms can also identify potentially harmful information and allow volunteers to review it first. According to Windisch et al. (2022), early detection of harmful content and prompt response are critical for combating hate speech. Rapid action enables volunteers to intervene with empathy before situations worsen.

Supportive Policies that Encourage Change

Governments can play a big role in promoting empathy-based methods. The European Union, for instance, backs projects like the No Hate Speech Movement by the Council of Europe. This program teaches young people to fight hate speech through online campaigns, workshops, and school programs (No Hate Speech Youth Campaign Website, n.d.).

Teamwork across countries is also key. The EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA) forces tech platforms to be transparent and accountable, aiming to make the internet safer. It also pushes for shared rules across borders to avoid uneven laws and ensure consistent action against harmful content (European Commission, 2022).

Empowering Users to Make a Difference

Regular users are key to a safer internet. Providing ready-to-use replies like, “I get you’re upset, but being aggressive won’t solve anything,” can make online talks more helpful.

Another idea is encouraging users to support kind comments. A “Like Justice” campaign could push people to “like” empathetic posts, which might also train social media algorithms to favor positive content over hate.

Working Together for Change

There’s no single solution to stop online hate speech. But combining empathy-based methods, new tech, smart policies, and daily user actions can make a big difference. Governments, tech companies, nonprofits, and users all have roles to play in building a kinder internet.

Conclusion: Building a Better Internet Together

Stopping hate speech online is complicated. It’s about finding the right balance between free speech, empathy, technology, and smart rules. Switzerland’s Stop Hate Speech project shows that when you mix empathy with good tech, like the Bot Dog algorithm, you can make a real difference.

No plan is perfect. But when governments, tech companies, regular people, and communities work together, it’s possible to build a safer and kinder internet. Every time you respond with kindness instead of anger, you’re making things better.

So, what’s next? How can empathy, technology, and good policies work together to stop online hate? Your voice matters. What you do today can help create a better internet tomorrow.

References

Deutsche Telekom AG. (2023, January 12). Countering hate speech on the Internet with “Bot Dog. Telekom.com. https://www.telekom.com/en/company/details/countering-hate-speech-on-the-internet-with-bot-dog-1023756

European Commission. (2022, October 27). The EU’s Digital Services Act. European Commission. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/digital-services-act_en

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating Platforms. John Wiley & Sons.

Hangartner, D., Gennaro, G., Alasiri, S., Bahrich, N., Bornhoft, A., Boucher, J., Demirci, B. B., Derksen, L., Hall, A., Jochum, M., Munoz, M. M., Richter, M., Vogel, F., Wittwer, S., Wüthrich, F., Gilardi, F., & Donnay, K. (2021). Empathy-based counterspeech can reduce racist hate speech in a social media field experiment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(50), e2116310118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2116310118

Khalid, A. S., & Dickert, S. (2022). Empathy at the Gates: Reassessing Its Role in Moral Decision Making. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.800752

Kubli, M. (2024). Digital Democracy Lab. Digital Democracy Lab. https://digdemlab.io/

lang.footer-gds. (2025). Switzerland Strategy – Measures. Switzerland Strategy. https://digital.swiss/en/action-plan/measures/stop-hate-speech-identifying-online-hate-speech-using-algorithms-and-strengthening-public-discourse

No Hate Speech Youth Campaign Website. (n.d.). No Hate Speech Youth Campaign. https://www.coe.int/en/web/no-hate-campaign

Press Release. (2002). Resuscitation, 55(3), I. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0300-9572(02)00412-4

Public Discourse Foundation. (2023). Public-Discourse.org. https://www.public-discourse.org/

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F. R., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021). Facebook: Regulating Hate Speech in the Asia Pacific. Ses.library.usyd.edu.au. https://doi.org/10.25910/j09v-sq57

Stop Hate Speech. (2021, June 9). UZH – Digital Society Initiative – Democracy. https://democracy.dsi.uzh.ch/project/stop-hate-speech/

Stop Hate Speech. (2025). Stophatespeech.ch. https://stophatespeech.ch/

Tworek, H. (2019). An Analysis of Germany’s NetzDG Law †. https://www.ivir.nl/publicaties/download/NetzDG_Tworek_Leerssen_April_2019.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Windisch, S., Wiedlitzka, S., Olaghere, A., & Jenaway, E. (2022). Online interventions for reducing hate speech and cyberhate: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 18(2). https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1243

Be the first to comment