Upload your cat, your homework, your lifestyle — just make sure it’s straight.

Cat Tax, Free English Tutors, and Cultural Imposition

One of the biggest online trends in January 2025 was without a doubt the arrival of the “TikTok refugees.” As the U.S. government was about to enforce a TikTok ban, a wave of desperate users fled the app and settled on a new platform — RedNote, known in China as Xiaohongshu. Also run by a Chinese company, RedNote shared a similar content style and algorithm-driven vibe, becoming a new home for these users who jokingly called themselves “TikTok refugees.”

The first ticket to board this new Noah’s Ark was paying the “cat tax” — a playful rule invented by Chinese users asking the newcomers to share cute photos of their cats (dogs, hamsters, or any other pet were accepted too).

Besides paying the cat tax, TikTok refugees started offering free English tutor services to Chinese users. They helped correct English homework, exchanged stories about living costs, and shared fun cultural differences. Everything seemed unusually open, warm, and friendly — almost like the concept of a global village was coming back to life after the 2000s.

Then, as expected, discordant voices began to appear.

On January 14, 2025, a U.S. user who identified as non-binary published a post: “Is it true rednote doesn’t like gay people?” Within hours, the post was deleted.

The next day, they uploaded a follow-up saying they would leave the platform. But this time, they received homophobic comments, some accused them of “cultural imposition.” Not long after, this post was also removed by the system.

That same day, another TikTok refugee was also censored. She had written, “Hello everyone, I am a lesbian from the United States.” The post was taken down shortly after, and her account was suspended.

(Of course, LGBTQI+ users weren’t the only ones being censored. Other targets, according to users, included Jewish people, anime series like My Hero Academia banned in China for referencing wartime history, and user’s cleavage.)

Zero-Cost Homophobia vs. Silenced Posts

If you search “同性恋”(homosexual) on RedNote, you’ll see a lot of related posts. So the topic isn’t completely forbidden…

But it’s definitely sensitive.

As mentioned earlier, some TikTok refugees got censored just for coming out or asking if the platform “likes gay people.” There are even more examples from native users. Below is one I found after searching for just three minutes:

I fully believe this user’s experience because I had a similar one. On March 2, 2024, I posted “Happy Mardi Gras🌈” — it only received 6 views. For comparison, another post I made around the same time titled “Selling IKEA lightbulbs,” which also had zero likes, was viewed 465 times.

And if you scroll a bit more through the “同性恋”(homosexual) search page?

You’ll also see lots of hate speech, like this one:

This time it took me even less time — just one minute — to find the comment above. I reported it right away.

Luckily, the platform responded fast and told me the comment had been handled. I checked the post — and yes, the comment was gone.

But when I switched accounts and checked again, it was still there.

So I searched “what’s the problem with rednote’s report system” — and found lots of similar complaints. Yes, this is how RedNote works: when you report a comment, it may be hidden from your view, but that doesn’t mean it’s actually removed. Often, the user who posted it faces no consequences. In other words, posting homophobic content on RedNote costs almost nothing — even though the platform’s community guidelines call for “kind and respectful communication.”

Because RedNote’s moderation system is a black box, it’s hard to say whether this behavior specifically targets LGBTQI+ users. It’s possible the platform shows the same passive attitude toward other types of content that aren’t politically sensitive. As a profit-driven platform, it may simply lack the incentive to regulate more strictly. Still, this kind of passivity aligns with what Gillespie (2010, 2015) describes: platforms often present themselves as neutral technologies, yet intervene in public discourse in selective and biased ways. In RedNote’s case, a weak reporting system lets hate speech spread, while its filters quietly shrink the space for LGBTQI+ voices. And this kind of intervention comes at almost no cost — the platform “enjoy[s] all the right to intervene, but with little responsibility about how they do so and under what forms of oversight” (Gillespie, 2018, p. 278)

Platform Nine and Three-Quarters for Lesbians

If we go deeper into the experience of queer users, we find even more signs of technical suppression.

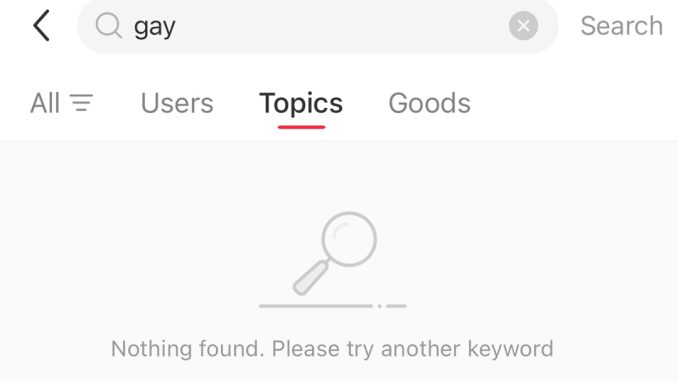

Searching “gay,” “lesbian,” or “queer” still brings up many posts. Everything looks fine — if you ignore the occasional hate speech.

But once you switch to the “Topics” tab, the system says: “nothing found.”

Were the topics deleted? No — they’re still there, just hidden.

To find them, you need to search for a post with one of these hashtags, then click into the tag from there.

And bam! — a hidden world opens up.

This “search trick” is like finding Platform Nine and Three-Quarters. It shows the platform’s blurry strategy — giving LGBTQ+ users a little space, while reducing their visibility.

Actually, #gay, #lesbian, and #queer are not the main spaces where Chinese lesbians gather. These words are too “direct,” too “attention-grabbing,” and attract both hate speech and censorship.

For example, on RedNote, the most common tag for “lesbian” is #le — a shortened version. Compared to #lesbian, #le has 133 times more views (2.2 billion vs. 16.6 million).

“Le” is a smart shortcut — it avoids triggering moderation but still carries a clear identity. It’s also easy to remember and spread. Today, #le is the most used lesbian tag across major Chinese platforms.

Another popular tag is #陈乐 (Chen Le), a famous Chinese lesbian influencer. Users often use #陈乐 to replace or supplement #lesbian and #le. Its view count is nine times that of #lesbian.

After TikTok refugees arrived, #wlw (women who love women) also caught on in Chinese lesbian spaces. This tag is low-profile and carries a small “knowledge gate,” which makes it harder to find but safer to use. It has already gained 252 million views and over 2 million posts.

These hidden tag strategies and the large gap in view counts reflect how LGBTQI+ users are carving out small spaces to breathe under platform pressure. Using coded expressions—like abbreviations, metaphors, or softer wording—has been a long-standing way for queer communities to survive censorship. In a space filled with hate speech, these strategies also serve as a form of protection.

However, as hashtags like #le and #wlw grow, the algorithm still finds them. Today, searching these tags on the RedNote topics page will again show “nothing found.” They’ve become the new Platform Nine and Three-Quarters.

Platform Homophobia…or State Homophobia?

Matamoros-Fernández (2017) proposed the idea of “platformed racism.” She argued that racism becomes more structured and widespread with the help of social platforms. Platforms act both as amplifiers — using algorithms, policies, and feeds to spread hate — and as governors — using opaque moderation systems that make things worse.

This idea fits RedNote’s treatment of LGBTQI+ users too. I call it “platform homophobia”:

Algorithmically, the platform monitors and limits posts with LGBTQI+ keywords.

Technically, it hides search paths to tags like #gay and #queer.

In governance, it lets hate speech go unpunished and offers no real oversight.

In short, the silencing of LGBTQI+ users is built into the system.

But blaming only “platform homophobia” isn’t enough. RedNote’s actions reflect deeper ideological values from the Chinese state.

Since launching the “Great Firewall” in the late 1990s, the Chinese government has kept strict control over online speech (Flew, 2021, p. 187). In 2015 and 2016, China passed the National Security Law and the Cybersecurity Law. These require platforms to censor content that “goes against the Party’s direction,” including criticism of the government, sensitive human rights and religion issues, and LGBTQ topics (Pacalon, 2023).

In this context, platforms are no longer neutral — they’re tools for state ideology. The suppression of LGBTQ content becomes “normal.” Meanwhile, hate speech often faces little regulation. For example, research by Guan and Chen (2025) on Weibo found that hate speech targeting LGBTQ groups often avoids censorship because it lacks “political sensitivity.”

Why? Because in official discourse, homosexuality is framed as a “symbolic threat” to Chinese culture — a foreign ideology seen as harmful to Confucian gender roles, collective values, and social stability (Guan & Chen, 2015). This official homophobia gives legitimacy to everyday homophobia, allowing hate speech to flourish on RedNote and reinforcing gender norms and prejudice.

So back to the original question: “Is it true rednote doesn’t like gay people?”

Maybe a better question is:

“Is it true China doesn’t like gay people?”

An Unwelcome Present and a Bleak Future

In 2021, a 26-year-old Chinese photographer named Zhou Peng (online name: Ludao Sen) ended his life. In his note, he said he was bullied since childhood for being too feminine — called a “sissy boy” — and lived in fear and isolation for years. That same year, China’s Ministry of Education and broadcasting regulator released documents calling to “prevent boys from becoming too feminine” and to eliminate “abnormal aesthetics” like “sissy” behavior. These policies turned social prejudice into national policy.

Today, if you search “娘炮” (sissy boy) on RedNote, you’ll still see many posts promoting “masculine values” and calling to reject femininity in men. This is happening on a platform with 80% female users — a platform already considered relatively inclusive. Even here, hate speech still thrives. On male-dominated platforms like Douyin or Weibo, attacks around “sissy boys” are even more common.

In this environment, LGBTQI+ people are not just dealing with personal bias — they are facing systemic hostility supported by platforms and even encouraged by the state. If things keep going this way, the future will bring more hate and more emotional damage. This damage isn’t always loud — it’s often quiet and constant. Many LGBTQI+ users may grow afraid to express themselves, retreat from public spaces, and start blaming themselves for all their struggles (Guan & Chen, 2025). This kind of internalized repression weakens both individual voices and collective strength.

So what can we do?

There may be no clear answer.

Before a bigger storm arrives, maybe the only thing we can do is hold onto each other tightly — in our own small Platform Nine and Three-Quarters.

References

Allen, K. (2021, February 4). China promotes education drive to make boys more ‘manly’. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-55926248

Cheung, E. (2025, January 16). As US TikTok users move to RedNote, some are encountering Chinese-style censorship for the first time. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2025/01/16/tech/tiktok-refugees-rednote-china-censorship-intl-hnk/index.html

Ewe, K. (2025, January 14). TikTok users flock to Chinese app RedNote as US ban looms. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c2475l7zpqyo

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. Polity Press.

Gillespie, T. (2010). The politics of ‘platforms’. New Media & Society, 12(3), 347–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444809342738

Gillespie, T. (2015). Platforms intervene. Social Media + Society, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115580479

Gillespie, T. (2018). Regulation of and by platforms. In The SAGE handbook of social media (pp. 255–278). SAGE Publications.

Guan, T., & Chen, X. (2025). Threat perception, otherness and hate speech in China’s cyberspace. Journal of Contemporary China, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2025.2475051

Lutkevich, B. (2025, February 18). TikTok bans explained: Everything you need to know. TechTarget. https://www.techtarget.com/whatis/feature/TikTok-bans-explained-Everything-you-need-to-know

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: The mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1293130

Mondal, M., Silva, L. A., & Benevenuto, F. (2017). A measurement study of hate speech in social media. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media (pp. 85–94). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3078714.3078723

Pacalon, T. (2023, July 4). LGBT cyber-activism in China: Between censorship and freedom. IGG. https://igg-geo.org/en/2023/09/08/lgbt-cyber-activism-in-china-between-censorship-and-freedom/#f+14884+3+14

Roberts, E. (2011). China’s Great Firewall. Stanford University. https://cs.stanford.edu/people/eroberts/cs181/projects/2010-11/FreeExpressionVsSocialCohesion/china_policy.html

State Council of the People’s Republic of China. (2015, July 1). National security law. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2015-07/01/content_2893902.htm

State Council of the People’s Republic of China. (2016, November 7). Cybersecurity law of the People’s Republic of China. https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-11/07/content_5129723.htm

Timmins, B. (2021, September 3). China’s media cracks down on ‘effeminate’ styles. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-58394906

Xiaohongshu. https://www.xiaohongshu.com/

Yip, W. (2021, December 15). China: The death of a man bullied for being ‘effeminate’. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-59576108

Be the first to comment