1 Introduction

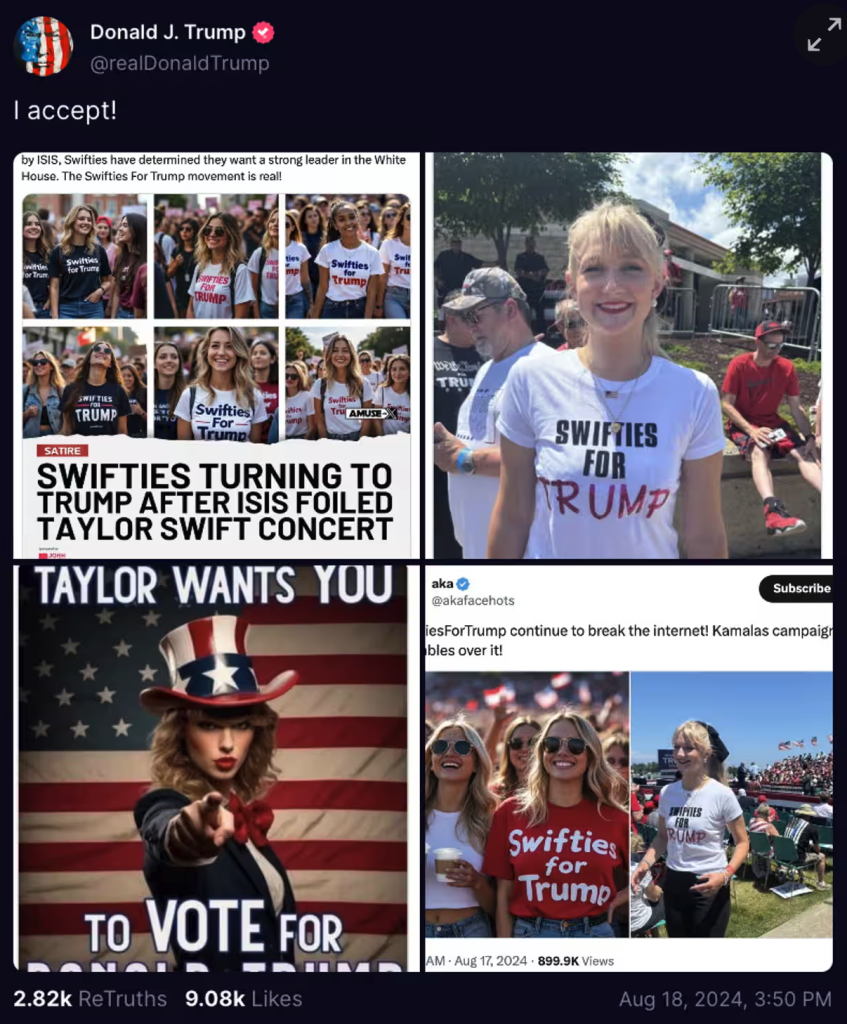

In 2024, when a photo of Taylor Swift appearing to support Donald Trump went viral online, people were stunned. Was it real? A joke? Something made by a fan? Before fact-checkers could catch up, the image had already flooded social media—sparking confusion, laughter, and outrage (Guardian, 2024).

Figure 1: Taylor Swift support Donald Trump (Guardian, 2024)

It turned out the photo was fake, generated by artificial intelligence. Just one more entry in a growing archive of AI-made images spreading online. It may have seemed harmless, but it pointed to something deeper: a cultural turning point. In a world where anyone can generate hyper-realistic visuals in seconds, the line between what’s real and what’s fake is starting to blur.

From celebrity gossip to political propaganda, from memes to media hoaxes. AI-generated images are no longer rare novelties. They’re changing how we understand reality itself. But this technology’s impact doesn’t stop at the evening news. It’s also transforming the world of visual art, putting enormous pressure on illustrators, designers, and digital creatives, whose work is now being mimicked—or even replaced—by AI.

In this blog, we’ll explore two growing concerns raised by AI-generated images:

- How human creativity is being undermined when artists see their work copied by AI.

- How our visual trust is breaking down, making it harder to tell truth from misinformation.

We’ll look at what’s at stake: for creators, for media consumers, and for society as a whole. And we’ll ask why, in this brave new visual world, one simple question matters more than ever: Is this image real? And does that still matter?

2 When Art Isn’t Human — The Crisis for Creators

In the past few years, AI-generated images have surprised many people and shaken up creative industries. Tools like Midjourney, DALL·E, and Stable Diffusion make it easy for anyone to create impressive visuals just by typing a few words. You don’t need to be an artist. For hobbyists and marketers, this feels like a dream. But for professional illustrators and designers, it feels more like a crisis.

The biggest concern is not just how fast or realistic these images are. It’s how these AI systems are trained. Most of them learn by using huge amounts of data taken from the internet. That data includes millions of artworks made by real people. Many of those artists never agreed to have their work used. They didn’t give permission, and they didn’t get paid. Yet their art was fed into machines to help those machines “learn.”

This situation is similar to an old story about a horse named Clever Hans. People believed he could do math and understand language. But later, scientists found out the horse was simply picking up tiny signals from the people around him, like facial expressions. He wasn’t actually solving anything. He was just reacting. AI does something similar. It doesn’t create from emotion or inspiration. It doesn’t understand beauty or meaning. It simply copies, mixes, and reflects what it has seen from human work. When we give it a prompt, it gives us back something that looks smart. But it’s just echoing the things we’ve already made. As the book Atlas of AI explains, artificial intelligence doesn’t think for itself. It reflects the systems, labor, and culture behind it. And often, it hides where the real knowledge came from (Crawford, 2021).

Figure 2: Clever Hans (Crawford, 2021)

2.1 Learned from us, but not ours.

Many artists feel hurt by this. On platforms like PIXIV, some creators have spent years developing their own styles. Now, anyone with the right keywords or AI tools like LoRA can copy those styles in seconds. Some artists even found their names being used as prompts in AI programs. It feels like they’ve become free consultants for the very thing that could replace them. This is more than a copyright problem. It’s about consent, ownership, and respect for creative labor. In the traditional world, artists get credit and protection. In the AI world, their work becomes just more data. Nobody asks them. Nobody tells them. Their art gets pulled into a system labeled as “open web data,” and that’s it.

The book Atlas of AI calls this the extractive logic of AI. It treats human creativity, labor, and even raw materials as things that companies can take and turn into profit. The people behind the work often stay invisible (Crawford, 2021).

2.2 The Legal Lag

In 2023, Getty Images sued the company behind Stability AI (Gilbert + Tobin, 2024). They said their copyrighted photos had been used without permission. Other artists have taken similar action. But the legal situation is unclear. Some people argue that using public images to train AI counts as “fair use.” Others say creators should have the right to say no, or at least to give permission in exchange for payment. For now, most artists have no protection. Some platforms like PIXIV allow users to tag their work as “AI-Generation” but there’s no strong system to enforce that rule (Pixiv Help Center, 2024). Meanwhile, AI-generated art is showing up everywhere—on websites, in competitions, even in job applications. It’s faster and cheaper than human-made work, and that’s making things harder for real creators.

Figure 3: AI-Generation Tag (Pixiv Help Center, 2024)

2.3 What We Lose

This isn’t just about jobs. There’s also something cultural at stake. We could lose visual diversity. AI doesn’t invent new styles. It repeats the patterns it already knows (Yiu et al.,2023). That usually means the most popular styles win—like anime, cyberpunk, or fantasy. Smaller, experimental, or culturally unique styles may be pushed aside. If we’re not careful, the future of creativity might become a loop of AI copying what it learned from humans, over and over again.

3 Seeing Isn’t Believing — AI Images and the Collapse of Visual Trust

When AI-generated images first started showing up online, many of them were just weird or funny. Fake celebrities, surreal landscapes, strange body shapes…It all felt like a harmless internet joke. But the technology matured quickly. Within just a year, the ability to create realistic visuals at scale began reshaping not only the world of art and media, but also something much deeper: our basic trust in what we see.

3.1 From Satire to Panic: The Rise of Synthetic News

In 2024, a fake image of Taylor Swift appearing to support Donald Trump spread quickly on social media platform X. The photo looked real. Her expression, the lighting—it all seemed believable enough to fool many people. Some even saw it as a genuine political endorsement.

Eventually, it was confirmed to be completely fake. But that didn’t slow it down. The image spread faster than any fact-check could catch up. And that’s the real issue. This wasn’t just a meme. It showed how the look of truth and the truth itself are drifting apart. In a digital world that rewards clicks and shares more than accuracy, AI-generated photos can shape what people believe long before the facts come in.

Terry Flew uses the terms “datafication” and “dataveillance” to describe this shift, where human behavior is turned into data and then constantly monitored, often for unclear purposes. In today’s algorithm-driven media systems, synthetic images aren’t just viral. They’re designed to go viral, pushed by platforms that aim to trigger emotional reactions and keep users engaged (Flew, 2021).

3.2 What Happens After the AI Image Is Made?

Once an AI-generated image hits the internet, its spread isn’t random. Social media platforms use algorithms to decide which posts to promote, hide, or show to specific users. These algo- rithms aren’t neutral. They’re built to increase engagement, which often means boosting the most emotionally charged content.

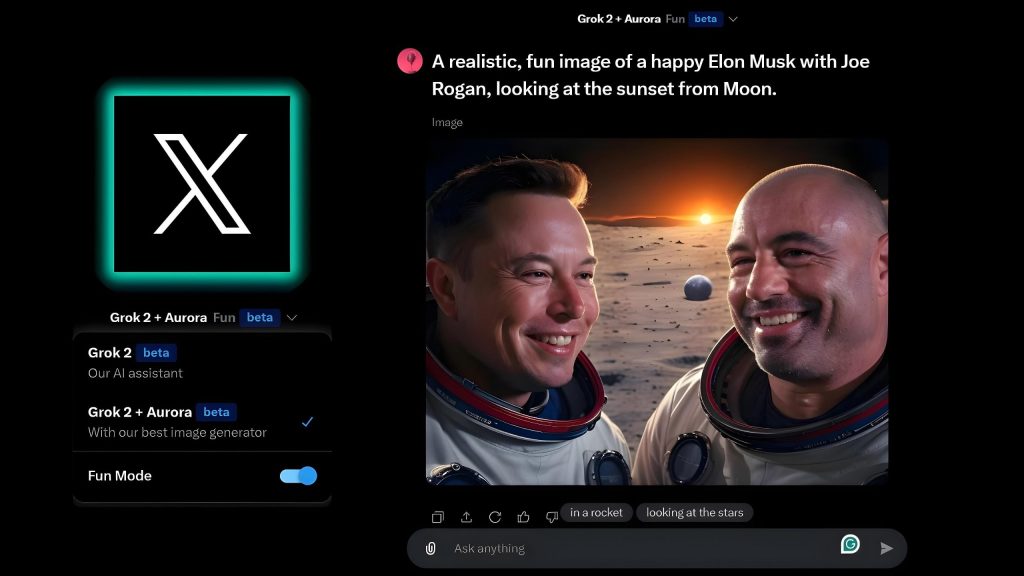

Figure 4: AI Image on X (Nishant, 2024)

In the case of the fake Trump–Swift photo, it wasn’t just the realism that made it go viral. It was the reaction—political outrage, confusion, laughter. The more people interacted with it, the more platforms like X, Facebook, or TikTok pushed it. Whether it was true didn’t matter. What mattered was that it got a reaction. This is how AI-generated misinformation slips past traditional gatekeepers. It doesn’t need to appear on the news to feel real. It just needs to trend (Zhou et al., 2023). And because algorithms show us content based on what we’ve liked or searched for in the past, the same image can mean very different things to different people. One person sees satire. Another sees a political scandal.

As Flew explains, this creates what he calls “carefully curated publics.” These are online com- munities shaped by what the algorithm thinks people want to see. When that content is AI-generated and intentionally misleading, we’re not just consuming fake news. We’re helping it evolve. Every time we share it, comment on it, or even pause to look at it, we help it spread (Flew, 2021).

3.3 The Erosion of Public Trust

All of this has serious consequences. Journalism relies on a shared understanding of what’s real. But when that shared sense of reality breaks down, meaningful public discussion becomes almost impossible. If any photo might be fake, if any video could be generated, people start to doubt everything.

In that kind of world, power doesn’t belong to the people who tell the truth. It belongs to the people who control what others see. Images become weapons. While journalists, fact-checkers, and platforms race to catch up, the tools of deception are developing faster than the tools of truth.

4 What Now? Regulation, Responsibility, and the Path Forward

So what do we do when we can no longer trust our eyes? What happens when AI-generated images spread faster than the truth, and the systems that deliver them are designed for en- gagement, not accuracy?

The answer isn’t to panic. It’s to push the right institutions—governments, tech companies, and regulators—to step up and build stronger rules and protections. We need clear laws and updated policies that can catch up with the speed of this technology.

4.1 Build Stronger Guardrails

Governments and regulators need to move faster than the technology itself. That’s not easy—but it’s necessary. Right now, many countries, including Australia, still lack specific laws for AI. Instead, they rely on voluntary ethical guidelines, which often have no real enforcement power.

But change is possible. The European Union’s AI Act officially came into effect on August 1, 2024. It introduces a risk-based approach to regulation. Some high-risk uses of AI are banned entirely, while others must meet strict transparency rules. This includes clear label- ing for AI-generated media used in politics and public communication (European Union, 2024).

Other countries don’t have to copy the EU’s approach exactly, but they can learn from it. With enough political will, it’s realistic to make things like AI content labels mandatory, give artists legal protection, stop unauthorized data scraping, and demand more transparency from algorithms.

4.2 Hold Platforms Accountable

Social media companies play a central role in spreading AI-generated visuals. But too often, they hide behind the complexity of their algorithms or the vague idea of “user-generated content.” That’s no longer acceptable. As Atlas of AI reminds us, these platforms are not neutral. They are extractive systems, built to profit from our attention, our data, and now, even our confusion (Crawford, 2021).

That’s why, moving forward, we need to demand more from these platforms. For example:

- Clearly label AI-generated visuals, especially in news or political contexts.

- Use visual warnings to mark manipulated or misleading content.

- Slow down the spread of unverified viral images with friction-based tools, like warning messages before sharing.

Some steps are already happening. Meta, Google, and OpenAI have announced watermarking or origin-tracking technologies. But these efforts are still early and mostly voluntary. Public pressure also works. It’s how we got fact-checking partnerships, content moderation policies, and bans on political deepfakes. Now we need to keep pushing.

4.3 Empower People, Not Just Systems

Finally, and maybe most importantly. We can’t leave the solution entirely to governments and tech companies. This is also a cultural shift. In a world flooded with synthetic media, media literacy becomes a basic survival skill.

As everyday citizens, we need to:

- Teach people how to question images—not just whether they’re real, but why they were made and what they’re trying to do.

- Support creators who make real, original, and traceable work.

- Reward transparency, not just viral success.

Across the world, artists, educators, journalists, and technologists are coming together to demand better standards for AI-generated images. If we join them, we can help shape the future, before it shapes us.

5 Conclusion

AI-generated images are dazzling and incredibly efficient. But when used carelessly, they can be dangerously persuasive. They challenge our ideas of creativity, authorship, and truth. These images are not going away. They’re changing how we create, how we report, and how we trust.Even as the technology moves fast, we still have choices. We can support real artists. We can question viral visuals. We can push platforms and lawmakers to take responsibility. The tools may be new, but the challenge is old—knowing what to believe, and why.

In conclusion, our job isn’t to fear AI. It’s to stay sharp, stay curious, and keep looking at the world with a critical eye.

References

Crawford, K. (2021). Introduction. In The atlas of ai: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence (pp. 1–21). New Haven, Yale University Press.

European Union. (2024). Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence [Accessed: 2025-04-07]. https : / / eur – lex . europa . eu / legal – content / EN / TXT / ?uri = CELEX : 32024R1689

Flew, T. (2021). Issues of concern. In Regulating platforms (pp. 79–86). Cambridge, UK, Polity.

Gilbert + Tobin. (2024). Getty images v stability ai: Navigating copyright in the age of gener- ative ai [Accessed: 2025-04-07]. https://www.gtlaw.com.au/insights/getty-images-vs- stability-ai

Guardian, T. (2024, August 24). Trump and taylor swift deepfakes raise alarm over ai-generated misinformation [Accessed: 2025-04-07]. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/ article/2024/aug/24/trump-taylor-swift-deepfakes-ai

Nishant, N. (2024). Xai launches aurora ai image generator for grok 2: Create ultra-realistic ai images [Accessed: 2025-04-07]. https://aitoolsclub.com/xai-launches-aurora-ai-image- generator-for-grok-2-create-ultra-realistic-ai-images/

Pixiv Help Center. (2024). What is the ”ai-generated” option in my work settings? [Accessed: 2025-04-07]. https://www.pixiv.help/hc/en-us/articles/11866194231577-What-is-the- AI-generated-option-in-my-work-settings

Yiu, E., Kosoy, E., & Gopnik, A. (2023). Transmission versus truth, imitation versus innovation: What children can do that large language and language-and-vision models cannot (yet)? Perspectives on Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916231201401

Zhou, J., Zhang, Y., Luo, Q., Parker, A. G., & De Choudhury, M. (2023). Synthetic lies: Under- standing ai-generated misinformation and evaluating algorithmic and human solutions, In Proceedings of the 2023 chi conference on human factors in computing systems. https: //doi.org/10.1145/3544548.3581318

Be the first to comment