Introduction: The Illusion of Privacy?

It’s a familiar feeling: you mention something in a chat with a friend, and the next day, an eerily specific ad shows up on your social media. It almost feels like your phone is listening—but what’s actually happening is often far more sophisticated. Through things like shared location data, browsing behavior, mutual app usage, and even Wi-Fi connections, companies can predict your interests without ever hearing a word. This kind of data-driven inference illustrates just how little control we have over our digital presence. While we routinely agree to long-winded terms and conditions, most of us have no real understanding of what we’re giving away. This blog explores how digital platforms quietly shape our online experiences and argues that real privacy reform—rooted in enforceable rights and public accountability—is urgently needed.

What Are Digital Rights? Why Should We Care?

To get to the heart of the issue, let’s start by unpacking what digital rights actually mean. Whenwe think about online life, it’s easy to focus on things like fast internet or being able to post freely. But digital rights go deeper. They include your right to control your data, be protected from surveillance, work in fair online environments, and speak freely without fear.

Goggin et al. (2017) categorise these rights as falling into four main areas: privacy, surveillance, work, and free expression. These aren’t abstract ideas—they shape how we live, communicate, and even protest online. If you’ve ever worried about who’s watching your messages or how your online history might be used against you, you’ve already bumped up against digital rights.

However, here in Australia, the situation isn’t great. Compared to Europe’s comprehensive data protection frameworks—especially the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)—Australia significantly lags behind in safeguarding citizens’ digital rights. We don’t have a national Bill of Rights, and our privacy laws are outdated. As Flew (2021) points out, tech giants like Meta and Google have become incredibly powerful, outpacing our ability to regulate them. In short, the internet’s evolving fast—our rights, not so much.

Privacy Under Platform Capitalism

Apart from the core elements of data collection, Platform capitalism operates largely behind the scenes, making most of its mechanisms invisible to users. In the example of TikTok, the user’s watch time as well as their content preoccupation determines their scrolling speed, and the type of content that holds their attention drives micro-interactions, including content they watch before scrolling away. Instagram also monitors what their users hover on and screenshot alongside likes. These actions, which appear inconspicuous, are logged for algorithm training that feeds ultra-customized content–algorithms that deepen digital silos—and ruthlessly target focus sabotage precision.

To build on this digital statement, face it: the economy of today uses personal information as financial assets. Packages are prepared and sold, from the clicks and scrolls to the posts one likes or hovers on. The major tech corporations do not provide free-of-charge services with altruistic intents; they exchange data for convenience.

Flew (2021) analyzes this by explaining the methods platforms use algorithms alongside predictive analytics to monetize our actions. Srnicek (2017) goes on to argue once a user is within a platform ecosystem, escaping becomes increasingly difficult—they depend on network effects that create a greater retention than departure incentive. Zuboff (2019) describes this famously as “surveillance capitalism” wherein users are under constant monitoring, tracking, and analysis of their online activities and this data is used to subtly steer our decisions—from what we buy to what we believe.

Here’s the worrying part: most of us don’t even realize it’s happening. Targeted ads, news recommendations, political messaging—it’s all shaped by our data. This isn’t just about selling products. It’s about shaping choices, often without us knowing. That’s not just a business issue; it’s a democratic one.

Case Study: RoboDebt and the Price of Profiling

Let’s bring it home to see the actual implications. The RoboDebt debacle in Australia demonstrates what can go wrong when governments begin acting like technology platforms. Centrelink used automated data-matching during 2016–2017 to identify welfare recipients purportedly owing money. The issue? The algorithm made mistakes—frequently. Thousands of people received debt letters with no checks, and many of them didn’t actually owe anything.

As reported by Goggin et al. (2017), the situation was a textbook example of poor transparency and computerized systems run amok. The consequences were serious, ranging from financial stress to emotional distress, with some tragic outcomes. It was not a system glitch—rather, a failure to safeguard citizens from harm.

Ultimately, the plan was shelved following public protest and a class-action lawsuit. In 2020, the Australian Government openly acknowledged that the debts were illegal and agreed to pay back over $700 million to over 400,000 citizens who had been unfairly targeted. A Royal Commission was undertaken to examine the collapse of the scheme, which concluded with a scathing final report in 2023. The report not only exposed the systemically flawed design and implementation of the RoboDebt program, but also criticised key public officials and ministers for negligence. But the harm was done. When governments employ platform-style models without checks, it’s ordinary citizens who end up paying the cost—along with their privacy, their wellbeing, and their trust.

The “Nothing to Hide” Myth: Public Perception vs Reality

Many people still claim, “I’ve got nothing to hide.” In Goggin et al. (2017) research, 65% of Australians agreed with that opinion. However, that same study also found 78% of respondents wished to know how data was being collected and utilized by companies. Clearly, people do care—it is just that the risks seem distant and muddled.

This nuance is further explained by Marwick and boyd (2014) with the term “networked privacy.” It encapsulates the notion that privacy is not only determined by one’s willingness to share personal insights, but also by how others choose to commemorate them online. Even the most private accounts are only one public tag away from exposure, and it is impossible to maintain complete obscurity in a world where one is being watched at all times. The idea that privacy exists purely as an individual phenomenon is impractical.

Privacy has become an impossible, unattainable goal. Data may be compiled and leveraged in unfair and exploitive ways. Algorithms might place undue scrutiny on a single user with incomplete data and individuals have no clear way to challenge these invisible decisions—if they are even aware of them in the first place. This is an extraordinary violation of someone’s privacy. It is also an astonishingly unjust thing to do.

Platform Responsibility and the Limits of Self-Regulation

Even when tech platforms claim to prioritize ethics, their actions often fall short. Take Meta’s Oversight Board, for instance. Although Meta presents its Oversight Board as an independent system for content review, all decisions ultimately remain under Meta’s control—undermining the idea of neutrality. It shatters all misconceptions surrounding impartiality.

This casts doubt on its neutrality. In the same context, numerous companies issue comprehensive sounding AI ethics policies that are not legally binding. Critics argue that these efforts are more about reputation management than true accountability. In the absence of legal benchmarks, self-regulation becomes more a way to buy time rather than initiate action.

For years self-regulation has been claimed by various technology companies. They publish internal privacy policies, transparency reports, and even have ethics boards. These are, at least from a distance, responsible actions. However, in the absence of legal repercussions or independent scrutiny, there is no oversight and business interests disproportionally outweigh user rights. When controversies arise like the Cambridge Analytica controversy or algorithmic discrimination, companies are quick to publicly apologize and pledge to do better with little meaningful action. Regulation has failed to keep pace with the astonishingly rapid development of digital technologies enabling platforms to construct their own rules with little pushback.

Self-regulation encourages public trust in companies, but without mechanisms to challenge potential misuse, that trust can be easily exploited. This imbalance of power makes clear why external, enforceable regulation is urgently needed.

Policy Failure and What Should Change

Given these challenges, what’s being done to fix all this? Honestly—not enough. Australia’s Privacy Act is over three decades old and doesn’t give individuals strong legal rights. Unlike Europe’s GDPR, which includes things like the right to be forgotten and clearer data consent rules, our laws rely on broad principles that don’t always hold up.

Flew (2021) argues that regulation simply hasn’t kept up with how fast platforms have grown. And that’s a big problem. Without updated laws, people are left to figure things out on their own—which usually means clicking “accept” and hoping for the best.

We require a rights-based approach to privacy. Clear rules, with real enforcement, and platforms that are actually held to those rules. Governments also need to invest in digital literacy. People shouldn’t need to be technology experts to understand their rights.

International Perspectives: Australia, the EU, and the US

Considering the global picture as a whole, it becomes apparent where Australia’s position is—and why it has plenty of room to improve. The European Union has taken the leadership role in establishing privacy standards through the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

It provides citizens with a set of rights over their personal information, including the right to grant or refuse permission, examine stored details, and ask that it be deleted. No less important, the regulation has effective enforcement mechanisms in place along with the potential for heavy fines, which serve to make it meaningful in practice. Whereas the GDPR is far from perfect, it has nonetheless become a model globally for privacy protection.

Conversely, the United States takes a piecemeal approach. In the absence of a general federal privacy act, the nation relies on sector-specific regulation—like HIPAA for healthcare information—creating uneven coverage. States like California have attempted to provide greater protection, yet enforcement is uneven and gaps persist. Since several key technology companies are headquartered in the US, the absence of unified national legislation has also spurred broader questions regarding how information is treated internationally.

Australia is in a precarious mid-position. Despite growing public pressure and repeated recommendations from government reviews, the privacy framework continues to be outdated and is rarely enforced in practice.

Compare this to international initiatives: it’s increasingly evident that greater protection is not just possible, but well within reach. All that’s missing is the political will to place public interest over corporate convenience.

Everyday Action: What Can the Public Do?

Though meaningful reform itself rests with governments and technology firms, that doesn’t preclude individual agency. Public pressure and involvement are still vital to driving reform. At a practical level, measures such as examining privacy controls, switching to encrypted messaging apps like Signal, or employing browser extensions such as Privacy Badger or uBlock Origin can provide control over information collection and dissemination.

Contributing to advocacy organizations—like Electronic Frontiers Australia or Access Now—also supports overall efforts towards accountability.

Outside of personal behaviors, political action is also important. Regardless of it being advocating with elected officials, signing on to policy-related petitions, or voting for those who support digital rights, individual actions can compound momentum towards comprehensive change. Community-based workshops and digital literacy initiatives further promote public awareness, allowing citizens to better understand their rights and insist on greater protections. Change is seldom decreed from above; it tends to result from persistent public pressure. And as more speak out, it becomes increasingly challenging for platforms and policymakers to turn a blind eye.

Conclusion: Towards a Rights-Based Digital Future

In conclusion, it’s worth taking a step back to see just how intimate—and simultaneously, how ubiquitously shared—digital privacy has become. It was something previously relegated to tech geeks or privacy champions, something that has grown to reach almost every individual’s existence, usually in discrete, unseen manners. The lengthening roster of scandals, breaches, and harms facilitated by data all point to a single conclusion: that digital spaces are highly surveilled, and the mechanisms in place are not user-centric.

If we’re to have a digital world based on trust, fairness, and self-empowerment, we must then start creating it with deliberateness. The truth is that privacy these days is about a lot more than app permissions or browser controls—At its core, privacy is about power—and that power remains firmly in the hands of platforms, not people.

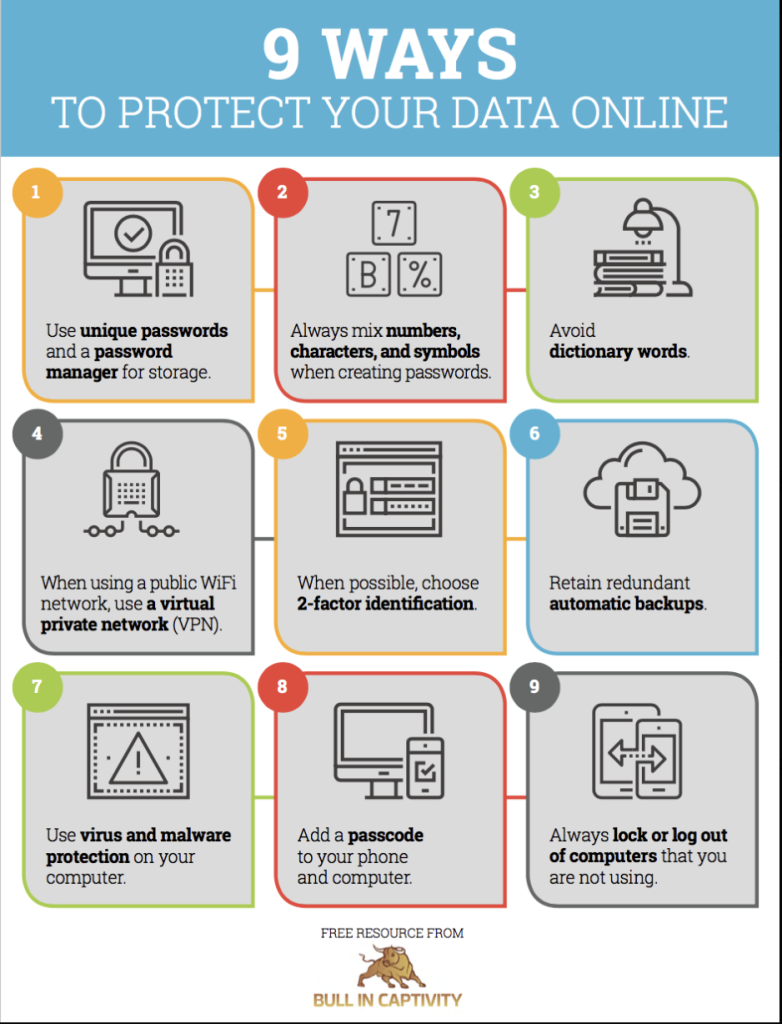

Solutions such as VPNs or private browsers provide temporary respite, short of solving the underlying issue: a digital ecosystem based on extraction and not on consent. Real progress means a fundamental realignment about how we value privacy—less as a secondary feature, but as a fundamental right.

As everything increasingly goes online—healthcare, schooling, money, participation in the lives of their cities—there will be a greater need for strong, rights-based privacy mechanisms. It’s not that we need improved technology, however. It’s improved governance: evolving legal norms, responsible platforms, and a cultural climate that sees privacy as a kind of dignity, a kind of agency, rather than as a secret.

References

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. Polity Press.

Goggin, G., Martin, F., & Dwyer, T. (2017). Digital rights in Australia. University of Sydney.

Marwick, A. E., & boyd, d. (2014). Networked privacy: How teenagers negotiate context in social media. New Media & Society, 16(7), 1051–1067. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814543995

Srnicek, N. (2017). Platform capitalism. Polity Press.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism. Profile Books.

OpenAI. (2024). ChatGPT (April 2024 version) [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com/chat

Be the first to comment