“There has been growing concern worldwide about the use of digital communication platforms for the dissemination of disinformation, misinformation, and ‘fake news’.”— Flew,Terry

The concern of disinformation and fake news

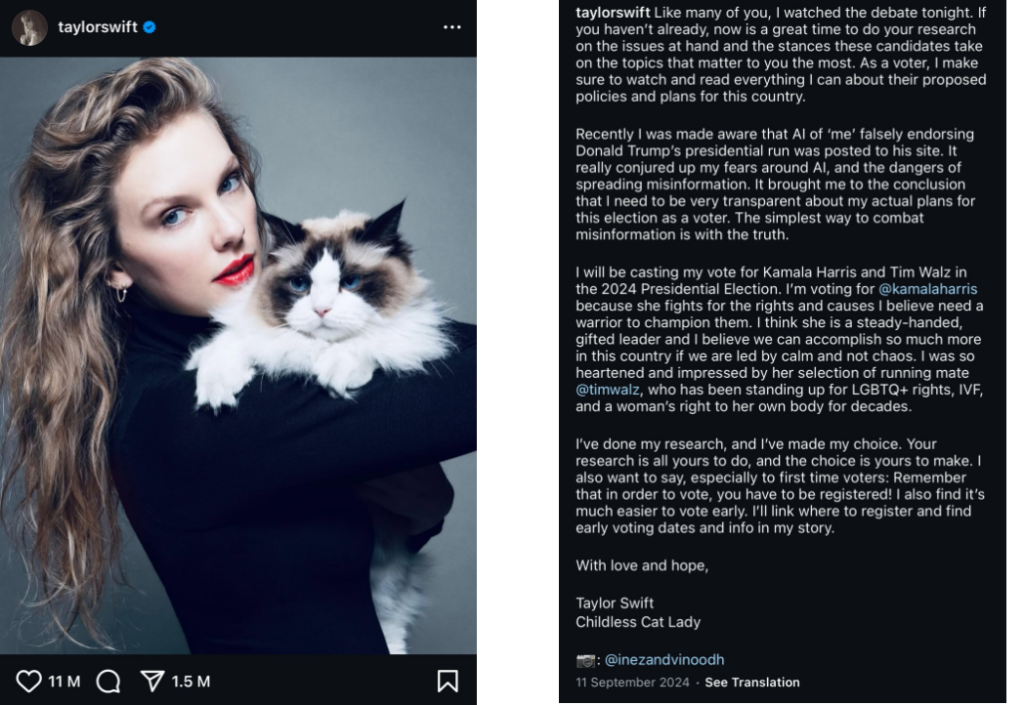

In August 2024, the photo of Taylor Swift voting for Donald Trump went viral on social media. The image looked convincing—crisp, well-lit, and emotionally charged. Swift stood near a ballot box, MAGA hat in hand, with a subtle smile that suggested political pride. But there was one major problem: it wasn’t real. This photo was made using AI, and it quickly stirred up a storm online, confusing voters and adding fuel to the misinformation fire during a key moment in the election.

Figure 1: Screenshot of Donald Trump’s post (from Truth Social)

After the U.S. presidential debate on September 10, 2024, Taylor Swift announced her political support for Kamala Harris and Tim Walz’s campaign by posting on Instagram. And she criticized the AI-generated images that Trump’s shared before, and expressed concern about the potential dangers of spreading misinformation.

Figure 2: Screenshot of Taylor Swift’s post (from Instagram)

This is a typical example of AI’s power to create misinformation that deceives and defrauds voters (Merica & Swenson, 2024). Due to the rise of digital platforms as the primary source for news, they’re also increasingly being exploited to spread false information. The line between truth and false is getting harder to see, especially when images, once trusted as evidence, can be easily edited to look incredibly real something have gotten tricky. According to Flew (2021) , stated that the widespread use of AI and deepfake tools has fueled the global surge in misinformation and so-called “fake news,” blurring the boundaries of credibility in digital communication.

Therefore, as AI technology becomes more advanced and accessible to use, distinguishing what’s real and what’s fake is no longer straightforward. From fake political endorsements to fabricated news footage, these are challenging public trust in media and shaping real-world decisions—from voting behavior to social unrest.

In this case, the Taylor Swift photo is more than just a viral moment—it’s a warning sign. In a world where seeing is no longer believing, the fight against digital misinformation has become more urgent, and more complex than ever before.

The growing threat of visual misinformation

In the fast-paced world of digital media, the rise of visual misinformation stands out as a major concern. Nowadays, the ability to edit images and videos has reached incredibly realistic levels. From deepfakes to edited visuals, distinguishing fact from fabrication is becoming harder and harder.

What makes this problem even more serious is that these digital platforms are becoming easily accessible to individuals (Flew, 2021). He also mentioned that, digital platforms now offer user-friendly interfaces, making it possible for anyone to produce convincing fake content. As these tools become more widespread, the risk for misuse in harmful ways increases rapidly.

For example, in September 2014, a disinformation campaign falsely claimed there was an explosion and toxic fumes at the Columbian Chemicals plant in Louisiana. These fake reports spread widely through fake Twitter accounts, YouTube videos, and spoofed news sites. However, no such incident occurred. The journalist Adrian Chen linked this “highly coordinated disinformation campaign” to a Russian organization, which is known as the Internet Research Agency (Jack, 2017). Thus, the creation of disinformation behaviors is no longer limited to experts and state actors, anyone with a mobile terminal can generate fake news in minutes. This technological shift has taken disinformation to an incredibly dangerous new level, particularly on digital platforms such as X(formerly Twitter), YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram, where visual content dominates.

Figure 3: Screenshot of YouTube video from the Columbia Chemicals misinformation campaign. (from JACK, 2017, p.2)

A significant increase in ‘social news’ is also the reason for the rising of fake news (Flew, 2021). The news acquired media platforms—Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp, WeChat, TikTok. According to the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, in 2017, 51% of U.S. news consumers rely on social media for their news, and across the thirty-six countries surveyed, this figure ranged from 29% in Germany to 66% in Brazil (Flew, 2021). Thus, the way individuals share news is changing fast, and social media is reshaping how stories spread around the world.

Can We Trust What We See?

“Artificial intelligence is now a player in the shaping of knowledge, communication, and power.“— Crawford, Kate

1.Difficulty in Detecting AI-Generated Images

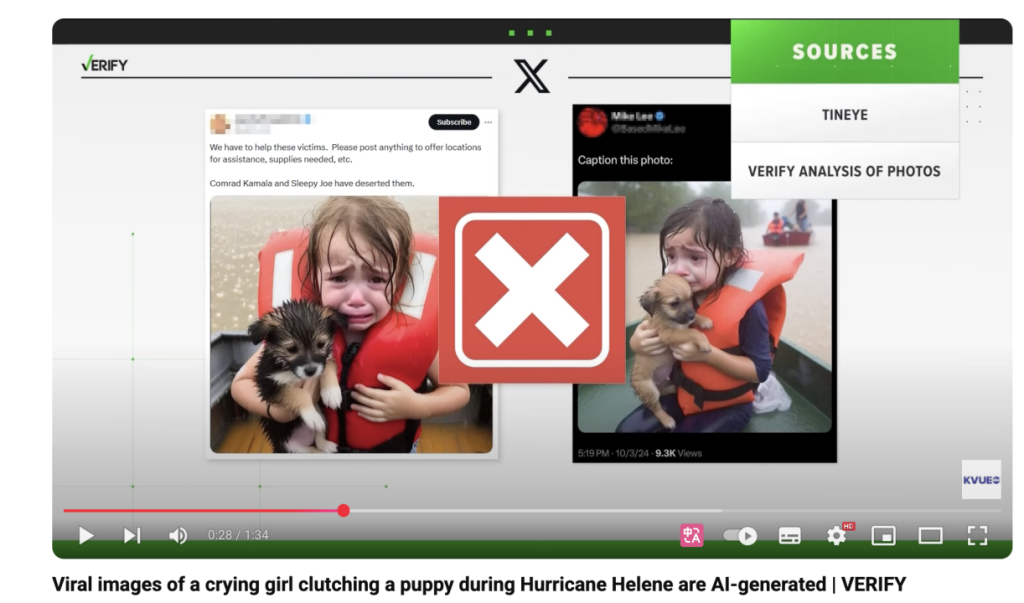

Deepfake technology, which can make AI-generated images become a serious problem. It utilize machine learning to create hyper-realistic photos and videos.These images can wrongly show political leaders, famous people, or past events.This level of realism is hard for ordinary viewers to see. It is also hard for professionals. They cannot tell if the image is real or fake right away. As shown in the figure 3, An AI-generated image showed a young survivor of Hurricane Helene. It got millions of views online, people around the world questioned where it came from. But it kept spreading and attracting individuals’ attention.

Figure 4: Screenshot of YouTube video from a crying girl clutching a puppy during Hurricane Helene (from YouTube)

2. Lack of Context Information

Fake photos are put in the wrong place or given false captions to trick people. The image looks real. But its meaning changes when the description is wrong or when it is not in the right context. People see these images and think they are real. They do not ask if they are true. This makes events unclear, especially in politics and social issues. People believe pictures more than words. These false images spread fast. They change opinions and create wrong ideas.

3. Rapid Spread

Social media and online platforms focus on content that gets attention. This helps fake images spread fast. People notice the problem late. By then, many have already shared these false pictures. This makes misinformation grow stronger.

4. Psychological Impact

People believe images that match their own ideas, even when they are not true. This makes fake pictures easy to accept and share. As they spread, they create false stories and misinformation.

The real threat isn’t just false information. It’s that people don’t know what to believe anymore.

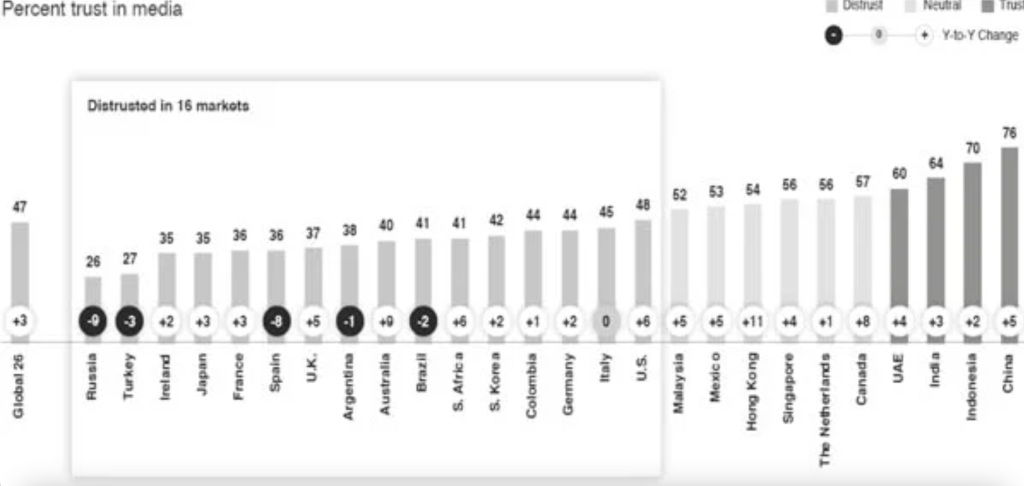

Trust in Media: A Global Perspective on Declining Confidence

Flew(2021) indicated that, people’s trust and confidence in traditional news media have been steadily decreasing. For instance, The Edelman Trust barometer stated that traditional media ranks as the least trusted major public institution, with the most respondents in sixteen out of twenty-six surveyed countries expressing distrust in news media (Edelman Data & Intelligence, 2020; see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Trust in Media across 26 Countries.(from Edelman Data & Intelligence, 2020, p. 42)

Futhermore, the pursuit of profit has fundamentally fueled the spread of fake news (Jack, 2017). He also mentioned that, digital platforms create structured systems that encourage the distribution of misleading or harmful content. For example, in the 2016 election cycle, thriving questionable news websites have published numerous unsourced, unreliable, or fabricated news reports (Jack, 2017). A significant number of these were profit-focused businesses, which is driven primarily by the opportunity to make money from clicks rather than by political motives. Apparently, Digital platforms themselves have also raised serious concerns about the reliability of information”.

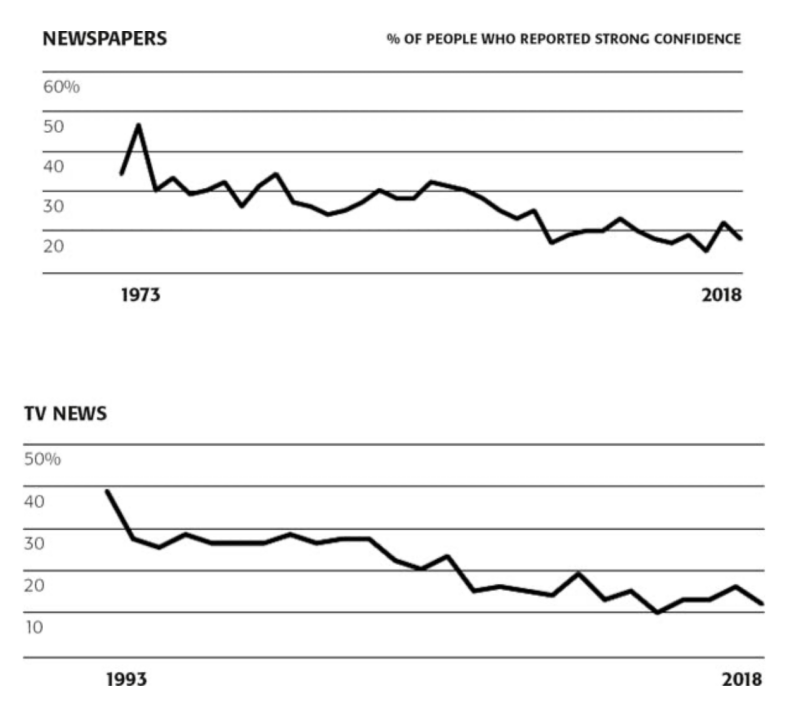

Flew (2021) states that the Gallup Confidence in Institutions Survey shows a steady drop in public trust in newspapers and television news in the United States. Zuckerman (Gallup, 2018; Zuckerman, 2019) also notes this decline, which has continued from the 1980s to today.

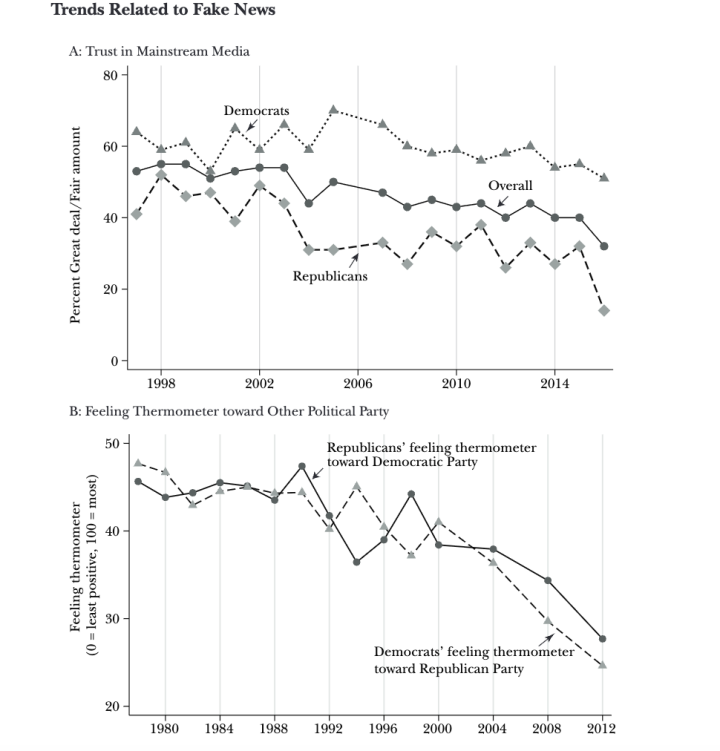

Public trust in institutions like the WHO, courts, and election offices is shrinking. Society is becoming more divided. Political polarization shows how each side views the other more negatively. In 2016, Gallup polls showed that Republicans’ trust in mainstream media fell sharply. Some link this to the rise of fake news.

Figure 6: Declining Trust in Newspapers and TV News in the United States. Source: Zuckerman, 2019, p.106.

Figure 7: Declining Trust in Newspapers and TV News in the United States. Source: Zuckerman, 2019, p.106.

But, on the other hand, the real threat isn’t just false information. It’s that people don’t know what to believe anymore.

Fighting Back: What’s Next in the Battle Against False Information?

To fix misinformation and fake news, journalism , governments, and users need to take action and make changes.

Stronger media literacy in digital spaces

It is essential for both journalists to develop stronger media literacy skills. They must check images before publishing, and they should look at the source, check metadata, and compare the image to known facts. It helps prevent the unintentional spread of false information. They cannot spread false or misleading pictures. They must show the truth and protect people from harm.

Users need to “do the check research”

Users must learn how to stop our foots before sharing, and question before trust.

Tools for Identifying Fake News Photos such as Snopes, FactCheck.org, and PolitiFact plays a important role in examining the accuracy of claims in news articles, social media, and political discussions. They can help us to tell the difference between what’s true, misleading, and completely false news.

Additionally, we need to critically think the digital media, we should question original sources, check the claims accuracy, which can help us become more responsible consumers of information. This YouTube video titled “How to Spot Fake News” provides many practical tips can be used in daily life, teaching individuals how to identify ‘fake news’ on how to identify false or misleading information in news stories.

Government must rebuild communication

Governments play a crucial role in regulating misinformation and misleading images, as these can shape public opinion, influence elections, and even incite harm. Across the world, policymakers are working to implement stricter controls, while navigating the delicate balance between security and free speech.

Germany’s NetzDG law is a strong example. It tells tech companies to take down illegal content in 24 hours or they will get up to of 50 millions fines. But there are still questions about how well platforms follow these rules and if these strict laws might cause too much content to be taken down.

Additionally, Australia also tried a law to deal with misinformation. It wanted to give big fines to tech companies that did not handle the risks of false information. The problem felt urgent after false stories spread online following violent events like the Bondi Junction stabbing. About 75% of Australians said they were concerned about the disinformation. However, in November 2024, this bill did not pass, because different political groups did not agree. The argument was mostly about choosing between rules and free speech. Some political factions were afraid the government would have too much control over what people say online.

Figure 8: Screenshot of Bill scrapped video (from ABC news)

Finding the right balance between rules and free speech is hard. But one thing is clear. Governments should not do nothing. New rules will probably need help from lawmakers, tech companies, and community groups. They will need to work together to make fair and useful plans.

Reference

Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211–235. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211

Crawford, K. (2021). Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. Yale University Press.

Denniss, E., & Lindberg, R. (2025). Social media and the spread of misinformation: infectious and a threat to public health. Health Promotion International, 40(2). https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daaf023

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating Platforms. Polity Press.

Government declares war on big tech, but can it actually win the battle? – ABC News. (2024, September 12). ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-09-12/david-speers-on-social-media-disinformation/104337130

Human Rights Watch. (2018, February 15). Germany: Flawed Social Media Law. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/02/14/germany-flawed-social-media-law

Jack, C. (2017). Lexicon of lies: Terms for problematic information. Data & Society. https://datasociety.net/library/lexicon-of-lies/

Merica, D., & Swenson, A. (2024, August 20). Trump’s post of fake Taylor Swift endorsement is his latest embrace of AI. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/trump-taylor-swift-fake-endorsement-ai-fec99c412d960932839e3eab8d49fd5f?

Peter, L. (2022, May 1). How Ukraine’s “Ghost of Kyiv” legendary pilot was born. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-61285833

Rancourt-Raymond, A. de, & Smaili, N. (2022, June 23). How to combat the unethical and costly use of deepfakes. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/how-to-combat-the-unethical-and-costly-use-of-deepfakes-184722

Be the first to comment