In today’s digital world where everyone has a platform and information is just a scroll away, news seems to be everywhere. But have you ever paused to wonder: Is what I just saw actually true? Has that ‘breaking story’ been verified by anyone, or are we just taking it at face value? Fake news and disinformation are no longer just a media concern, but a social crisis that shakes the foundations of democracy. Especially in the ‘post-truth’ era, people are judging truth less by facts and more by how it makes them feel (Waisbord, 2018).

What is Fake news, Disinformation, Misinformation?

Fake news refers to content that looks like real news but is not. It is often not vetted through any editorial process, which means there is no way to ensure the accuracy and credibility of the information. Sometimes it is meant to mislead, other times it is for profit or entertainment.

Misinformation is false information shared by mistake. There is no intent to deceive, but it can still do harm.

Disinformation, on the other hand, is intentionally false and often related to political, economic, or ideological agendas. It is the kind of content deliberately crafted and spread, especially on social media, to manipulate public opinion, sway elections, or sell lies. Think government propaganda or corporate spin dressed up as news (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017).

The Perfect Storm for Fake News: Platforms, Algorithms, and Ourselves

You might be wondering: ‘Why does fake news seem to be everywhere these day?’

The short answer? Because in the digital age, everyone can be a ‘media outlet.’

All you need is a smartphone and a social media account. You do not need fact-checkers, editors, or any background in journalism. And thanks to ad revenue models driven by clicks and views, even the most outrageous, misleading content can make serious money. The more shocking or emotional headline, the more likely it is to go viral, and then directly translates into profit.

What’s more, social media has become a primary news source for millions. According to the Reuters Institute Digital News Report (2017), 66% of Brazilians and 51% of Americans were getting their news primarily from platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. That trend has only grown in recent years.

To be honest, we are not just passive consumers, we are active participants in the spread. Likes, shares, comments, all the engagement features we love, do not reward truth. They reward emotion. Social media algorithms are designed to amplify what gets a reaction, not what gets it right. Studies have shown that false news spreads faster and further than true news, not because it is better, but because it is more clickable (Lazer et al. 2018).

In short, the system is not broken. It is working exactly as designed, and fake news is thriving because of it.

On top of that, in highly antagonistic societies, people are more likely than ever to trust information that aligns with their existing beliefs, regardless of whether it is true. This phenomenon is not just about personal bias, it is deeply reinforced by the digital platforms we use every day.

Social media algorithms are built to keep us engaged, and they do that by feeding us more of what we already like. The result? Filter bubbles and echo chambers. Digital environments where we are surrounded by voices that sound just like ours. Over time, this insulates us from opposing viewpoints, reinforces our preconceptions, and drives us deeper into ideological corners. The more divided we become, the easier it is for misinformation to thrive (Kreiss, 2018).

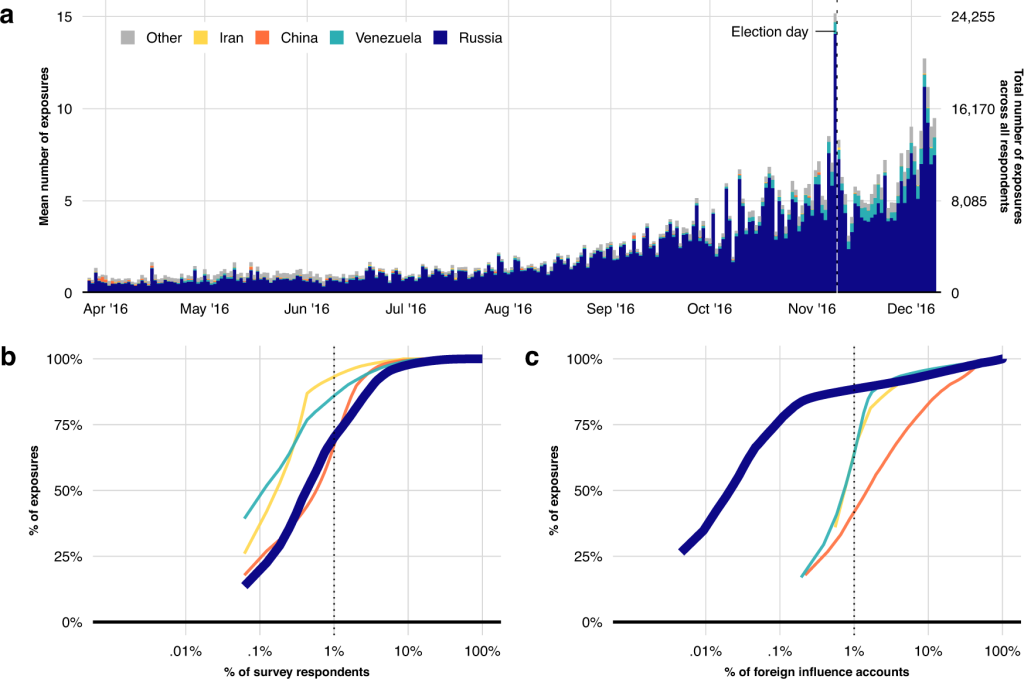

But the stakes go beyond personal opinion. In recent years, social media has been weaponized as a geopolitical tool. Take the 2016 U.S. presidential election, for example. Russia’s Internet Research Agency (IRA) created thousands of fake accounts posing as American citizens. These accounts did not just push support for one candidate while discrediting another. They deliberately targeted hot-button issues like race, religion, and immigration to stir outrage and deepen existing rifts in American society.

That same year, during the Brexit referendum, a similar pattern emerged. Investigations later revealed coordinated efforts again linked to Russian influence campaigns to sway public opinion and amplify pro-Brexit sentiment through misleading or polarizing content on social media.

This kind of state sponsored disinformation is far more dangerous than a viral fake news or an individual spreading a rumor. It is organized, strategic, and designed to destabilize democracies from within, by exploiting the platforms we rely on to stay informed. The result? A public increasingly skeptical of traditional news sources, and a society more fragmented than ever before (Benler et al.2018).

Who Creates Fake News? And Who Pays the Price?

The motivations behind creating fake news boil down to two things: money and ideology.

Let’s start with profit. During the 2016 U.S. presidential election, a group of teenagers in Veles, Macedonia, discovered they could make a small fortune by running pro-Trump websites filled with sensational but false headlines. Their goal was not to sway the election or spread propaganda. They just wanted clicks that meant ad revenue. As one teen told a reporter, they did not care about politics, they just wanted to make money. But the content they created ended up being shared millions of times, influencing real political discourse far beyond what they imagined (Subramanian, 2017).

Then there is ideology. Some fake news producers are deeply motivated by their political or cultural beliefs. Take InfoWars, for example, an American far-right media platform founded by conspiracy theorist Alex Jones. It has pushed everything from Sandy Hook shooting denialism to anti-vaccine rhetoric. By feeding into the fears and biases of its audience, InfoWars has built a loyal following, and a lucrative business model (van den Bulck & Hyzen, 2020). The more extreme and controversial the content, the more engagement it drives, and the more money it makes.

But fake news does not spread itself. We, the audience, play a big role too. Even when we think we are just “searching for the truth,” studies show we are more likely to engage with content that feels right emotionally, even if it is factually wrong. One of the big reasons fake news keeps spreading isn’t just because people are fooled — it’s because it feels good. For some, it is the relief of finding something that confirms what they believe. It is emotional comfort, outrage, or moral satisfaction that makes fake news keeps thriving. It is not only related to misinformation, but also psychological rewards we get from seeing the world the way we want it to be.

How Does Fake News Challenge Digital Governance?

In the world where truth and false are hard to distinguish and ideological polarization is rampant, digital policies are confronted with unprecedented challenges.

On the one hand, if governments force platforms like Facebook and Twitter to delete fake news and disinformation, they may be accused of censorship or infringement of freedom of speech. On the other hand, if governments do nothing, disinformation will spread fast. This may make people to become more divided, and no longer trust each other, or even lead to violent. This is a high-risky balancing act to protect free speech and prevent the harm that fake news can cause.

Besides, the lack of algorithmic transparency also makes the problem worse. Social media platforms do not explain how their recommendation systems work, so the public is also unaware of which contents will be given priority for recommendation. But studies and leaked documents have given us some clues. They show that the algorithms often push content that is emotional or extreme, because that kind of content keeps people clicking and scrolling. Sadly, this also creates the perfect space for fake news to spread.

Even more complicated is the global nature of misinformation. Fake news does not care about national borders. For instance, during the 2016 U.S. election, Russia’s Internet Research Agency used fake accounts and posts to try to influence American voters. Similar tricks have been used in places like Europe, Latin America, and Asia. Some people have also accused China of spreading misleading stories about COVID-19 and global politics. All of this raises a big question: in a world so connected online, who really controls what we see and share? And who has the right to protect?

Based on this situation, many democratic countries are trying to find the best balance: How should we protect freedom of speech while not becoming an accomplice in the spread of lies? The answer is not straightforward, but the urgency of taking action is unprecedented.

How Should We Respond?

One of the most important things we need to do to prevent fake news is to have better rules. The government should hold social media companies accountable for more, ensuring that the content disseminated on their platforms complies with relevant laws and ethical norms. Meanwhile, they still need to safeguard the right of the public to express freely. Balancing this is not an easy task, but some countries have already taken strong actions.

Take the EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA) as an example. This landmark law forces tech giants to remove illegal and harmful content, including fake news and disinformation more quickly and transparently. It also requires platforms to explain the working principles of their algorithms. This is an important step towards making them accountable for the content they present to us.

At the same time, Australia’s News Media Bargaining Code requires companies like Google and Facebook to pay news outlets for their content. This helps support the production of reliable journalism. Not only does this assist struggling media organizations, but it also shifts some of the financial power away from tech giants and toward reporting that serves the public interest.

But just regulation is not enough. We also need to build a media ecosystem that is independent and trustworthy, one that values fact-checking, transparency, and strong editorial standards. Independent journalism still plays a vital role in holding power to account and providing reliable alternatives to the noise we hear online (Waisbord, 2018).

And finally, we must invest in digital literacy. In an age where anyone with a smartphone can publish and share content, everyone of us has become part of the information supply chain. That means we all carry some responsibility. Schools, communities, and even news outlets should prioritize media education, teaching people how to verify sources, recognize bias, and reflect critically before hitting “share.”

Next time you see a viral headline or emotional post, pause for a moment and ask yourself: Is this really true? Why am I sharing it? In that small act of reflection lies the beginning of a healthier information culture.

In a Post-Truth Era, Let us Not Give Up on the Possibility of Collective Truth-Seeking

We are living in what many scholars call a “post-truth society” a world where facts are fragmented, narratives are polarized, and truth often takes a back seat to personal beliefs. In this environment, what is considered “true” often depends more on who you ask than on what the evidence says.

But just because truth has become harder to pin down does not mean we should stop striving for it. As media scholar Silvio Waisbord puts it, “to oppose the idea of a shared information space is to deny the possibility of truth as a collective goal” (Waisbord, 2018). In other words, when we give up on common ground, we also give up on building a better, more informed society.

Every time we choose to speak rationally, resist spreading a rumor, or fact-check a sensational headline, we are helping to protect something essential, our shared reality. And in an age where disinformation travels faster than ever, that small act of resistance matters more than we think.

Digital governance is not just a matter for governments or tech platforms. It is about all of us. It is about the kind of public space that rooted in trust, accountability, and a collective pursuit of truth we want to build.

References

Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211–236.

Benkler, Y., Faris, R., & Roberts, H. (2018). Network propaganda: Manipulation, disinformation, and radicalization in American politics. Oxford University Press.

Derakhshan, H., & Wardle, C. (2017). Information disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making. Council of Europe.

Edelman Data & Intelligence. (2020). 2020 Edelman trust barometer. Edelman.

Lazer, D. M. J., Baum, M. A., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F., … & Zittrain, J. L. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359(6380), 1094–1096.

Subramanian, S. (2017, February 15). Meet the Macedonian teens who mastered fake news. Wired.

van den Bulck, H., & Hyzen, A. (2020). Beyond fake news: The media logic of alternative facts. Communication, Culture & Critique, 13(1), 157–173.

Waisbord, S. (2018). The elective affinity between post-truth communication and populist politics. Communication Research and Practice, 4(1), 17–34.

Be the first to comment