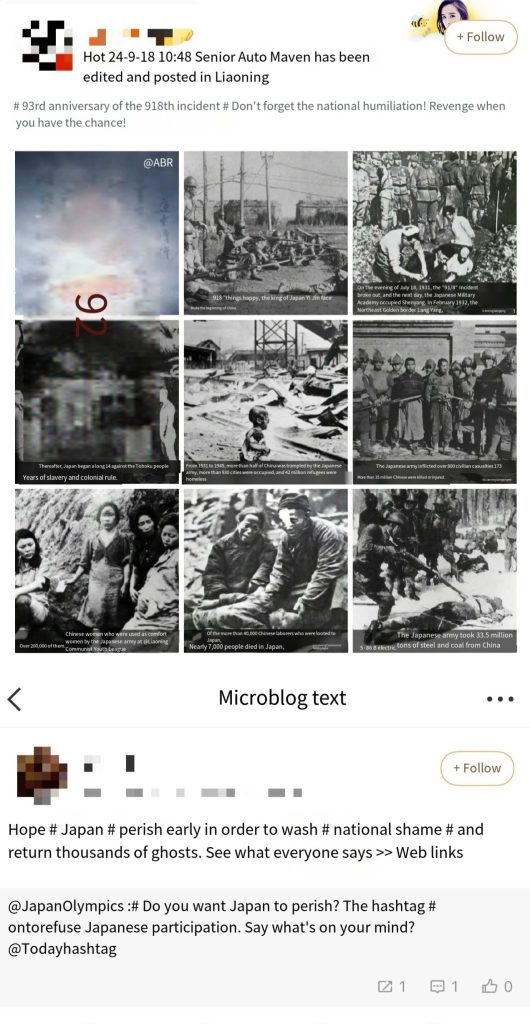

The 18th of September 2024 is not an ordinary day but a heavy historical memory in the heart of every Chinese person—the 18th of September 1931, when Japan launched its aggression and occupied the Manchurian region in the northeast of China. This event came to be known as the ‘September 18th Incident’. For every Chinese person, this day means national humiliation and the beginning of the long war of resistance against Japan.

On such a sensitive day, a 10-year-old Japanese boy in Shenzhen was stabbed by a stranger on his way home from school and died from his injuries. According to the police report, the attacker was a 44-year-old Chinese man, Zhong Changchun, who was sentenced to death on 24 January 2025 by the Shenzhen Intermediate People’s Court.

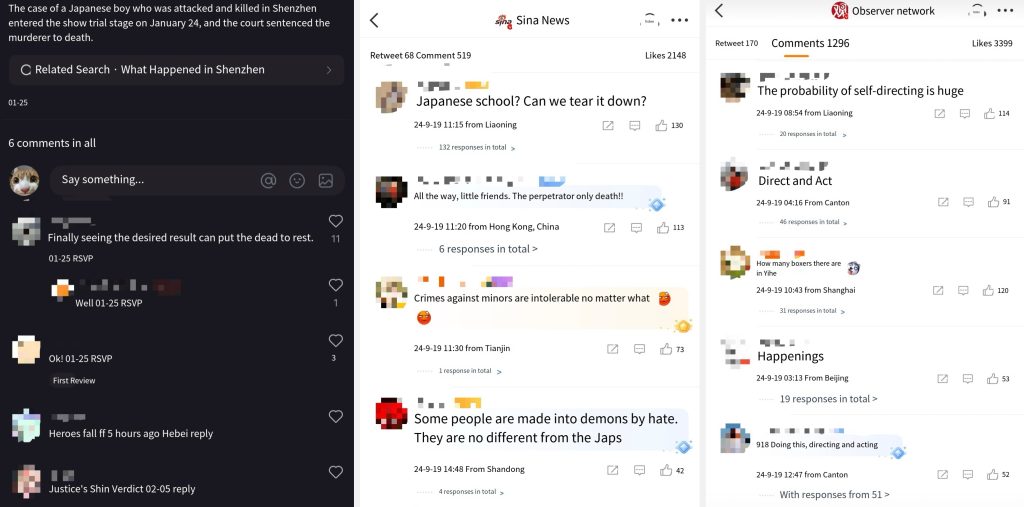

Although the court stated at the trial that the murderer’s motive was to gain attention on the Internet rather than explicit national hatred, the Japanese foreign minister stated directly that the murderer’s actions had been motivated by ‘malicious anti-Japanese’ comments that had long existed on the Internet. Meanwhile, Chinese online public opinion was extremely divided, with some netizens expressing shock and anger and condemning the violence while observing a moment of silence for the victims, while others openly expressed support for the perpetrator, even calling him a ‘national hero’ and the violence a ‘righteous judgement’. Some even suspected that it was a self-directed conspiracy theory by the Japanese. Such distorted hate speech makes people reflect on how cyberspace magnifies the latent malice in society.

Algorithms amplify hate: when platform logic meets nationalist sentiment

In recent years, nationalist sentiments on the Chinese Internet have been on the rise, especially when it comes to Japan, and much of the rhetoric has long since moved beyond discussions of historical controversies to open hostility and hatred. The assassination of students at a Japanese school in Shenzhen was not an isolated incident; in June of the same year, a Japanese mother and son were attacked outside their school in Suzhou. These incidents are not only shocking but also reveal a grim reality: the long-term accumulation of anti-Japanese sentiments in cyberspace is gradually overflowing into the real world and is even being transformed into violence by some extremist individuals.

As a matter of fact, Chinese netizens may not be very aware of the fact that there is some kind of algorithmic push behind the content they see when they are browsing social media apps such as Weibo, TikTok, and Xiaohongshu daily. Matamoros-Fernández (2017) once proposed a concept called ‘platformed racism’, which simply means that social media platforms are not a completely neutral messaging tool. Instead, the way these platforms operate-including their technical design, content recommendation algorithms, management policies, and the culture of interaction between users-combines to enable certain racially biased statements to be spread, amplified, and even repeated on the platforms and reinforced. In the case of the stabbing of a student at a Japanese school in Shenzhen, many comments with extreme anti-Japanese tendencies quickly became hot searches. In his study of Reddit, Massanari (2017) found that content that is offensive, extreme or emotionally charged is more likely to be pushed to the front of the platform and seen by more people. This is because the platform is more concerned with the ‘interaction rate’ and ‘number of clicks’ than whether the content itself is reasonable. Over time, this mechanism has created a ‘toxic culture’: as long as you speak strongly enough and take a hard stance, people will like you and the platform will give you traffic. This algorithmic push has given hate speech the appearance of ‘traffic justice’, making it seem like a ‘mainstream consensus’. It has even been mistaken by some as a form of ‘political correctness’, thus providing a kind of ‘moral endorsement’ for violent behaviour in reality.

Flew (2021) also provides an in-depth critical analysis of this. He points out that the business logic of social media platforms drives them to favour recommending content that quickly elicits a strong emotional response from users and can quickly generate a high level of interaction. While these algorithmic mechanisms are not initially designed to spread hate, but rather to maximise user engagement and platform revenue. However, this cost-effective design inevitably leads to a tendency for algorithms to promote controversial and emotionally provocative content, which in turn amplifies the nationalistic and hateful sentiments that already exist. Worse still, once such sentiments are consistently amplified, they can create a highly hostile climate of opinion in online communities. In the aftermath of the assassination of a Japanese school student in Shenzhen, some Chinese netizens who tried to speak out for the murdered Japanese children on social media, calling for a humanitarian stance and rational restraint, became targets of siege. They have even been labelled as ‘country-haters’ and ‘Jing-Ji elements’. This kind of attack on rational voices has evolved from an expression of emotions to organised and labelled cyber violence.

Online harm is essentially a form of group behaviour in which the platform’s algorithm plays the role of ‘amplifier’ and ‘catalyst’. Some users even take the initiative to organise ‘human flesh searches’ and ‘reporting actions’, making public the real identities, schools and work units of those who speak out, and then carrying out harassment and coercion in reality. This kind of public opinion violence not only puts the voices under great psychological pressure, but also further strengthens the ‘spiral of silence’ on the platform, making more rational voices choose to retreat. As Carlson and Frazer (2018) point out in their study of Aboriginal social media use in Australia, online violence tends to be collectivised, with those who are attacked being more likely to fall into a state of ‘digital silence’ while suffering from verbal abuse and stigmatisation. Over time, it is not that there is a lack of dissenting voices online, but that many people no longer have the courage to speak out.

The dilemma of digital governance: cultural and political games beyond technology

In the face of growing cyberhate and nationalism, the importance of digital governance policies has become increasingly evident. However, the effectiveness of governance remains limited in reality, not only because of technological lags, but also because of cultural perceptions and political positions in the governance environment.

Sinpeng et al. (2021) note that the governance of hate speech has become particularly complex in the Asia-Pacific region, especially in countries like China where politics and culture are highly intertwined. While platform technological tools can identify and filter specific types of content, they often appear powerless or even inactive when the speech is closely related to the country’s historical memory or dominant ideology. According to Jiang Ying (2012), online nationalism in China is often not entirely motivated by the spontaneous emotions of the people but is a form of expression that is highly attuned to the national narrative. In other words, this kind of ‘anger’ is sometimes encouraged, and even used as a means of responding to the outside world. Over time, although the platform can see the problem, it does not dare and is unwilling to intervene because it touches a politically sensitive line.

The stabbing of a student at a Japanese school in Shenzhen epitomises this governance dilemma. Although the police quickly characterised the case as an ‘isolated incident’ and attempted to ‘depoliticise’ it from the social level. However, discussions on the platform were quickly dominated by emotions, shifting to frames such as ‘patriotism’, ‘revenge’ and ‘national justice’. Some netizens openly viewed the attackers as ‘national heroes’. This rationalisation of violence is not accidental, but rather the result of a prolonged climate of hate speech.

What is more worrying is that although the Chinese government has in recent years launched campaigns such as ‘Operation Clean Slate’ to regulate the online order, the actual regulation has focused more on relatively ‘less politically sensitive’ areas such as vulgarity, rumours, and the culture of the rice circle, with little intervention in ultra-nationalist speech. There has been little systematic intervention in extreme nationalist discourse. On certain historical issues, officials even acquiesced to the existence of certain ‘hardline’ sentiments, and some social media platforms also chose to be permissive or silent in such a political atmosphere.

Behind this gesture of governance lies a deeper historical legacy. In Chinese society, the question of whether Japan has truly repented of its historical crimes has always been a lingering topic in public memory. The delay in real historical reconciliation between countries has left many people with no outlet for their emotions. This unresolved emotion is constantly evoked and spread on the Internet, and eventually, amplified by platform algorithms, it evolves into the legitimacy of violence in the name of ‘justice’, providing a psychological and moral basis for extremist behaviours.

What truly touched people’s hearts was a letter written by the father of the murdered boy after the incident. In the letter, he wrote: “I don’t hate China, nor do I hate Japan… I just want to prevent such a tragedy from happening again.” However, this letter was soon taken down in China’s cyberspace. Such a restrained and gentle expression failed to gain wide circulation. The disappearance of this letter is itself a form of social suppression of rational voices—a dangerous signal of ‘default extremism’.

When hatred can be liked, shared, and promoted by platform recommendation mechanisms, it is no longer just emotion—it becomes a product of intertwined commercial logic and social risk. Online violence does not stay online; it corrodes social trust, intensifies real-world confrontation, and ultimately creates immense pressure that the digital governance system cannot withstand.

The Triple Path to Breaking Down Hate: Platforms, Policies, and the Public

In the face of out-of-control nationalist sentiments and the spread of hate speech, it is far from enough to rely solely on platforms to delete and block posts. If governance always stays at the level of patchwork and incident-based emergency treatment, the next tragedy will only be a matter of time. Truly effective governance requires a systematic reconstruction of platform mechanisms, policy design and public awareness, starting from the fundamental structure.

Platforms, as ‘gatekeepers’ of content distribution, cannot continue to pretend that they are ‘neutral’ technological tools, as Gillespie (2018) has pointed out, platforms are not simply ‘conduits’, they are themselves shapers of culture and politics. The more platforms emphasise ‘neutrality’, the more likely they are to allow harmful content to gain dominance. Therefore, platforms must assume genuine social responsibility at the design and institutional levels.

Today’s recommendation systems automatically push the most controversial and emotionally charged content to more people. Once these contents become ‘traffic codes’ on the platform, it is difficult to be curbed. Therefore, platforms should establish a ‘high-risk content warning’ mechanism, such as identifying which topics are too emotionally charged and spread at an abnormal rate, and then proactively reduce the recommendation of such content. At the same time, platforms should set up content review teams with the ability to understand history and culture, so as to avoid misjudging nationalist-packaged hate speech as ‘user consensus’. For users who are attacked for expressing rational views, platforms should also set up a rapid response mechanism, such as assisting in reporting, hiding sensitive information, and even providing legal help.

Moreover, relevant laws and regulations should also be formulated at the policy level. If the law fails to clearly define what constitutes ‘cyber hatred’, platforms will have no way to deal with it, and governance will lack vigour. The government should promote the formulation of specific rules, such as setting up a special mechanism for guiding public opinion during historically sensitive periods (e.g., anniversaries and diplomatic disputes) to prevent emotions from getting out of control.

Finally, to change the situation, the public first needs to enhance their basic media literacy. Schools should teach students from an early age how to judge true and false information, how to recognise emotional manipulation, and how to distinguish between ‘patriotism’ and ‘hatred’.

A healthy cyberspace is one in which not everyone says the same thing, but in which everyone can express different opinions in a safe and secure environment. There must be a mechanism for platforms, a bottom line for policies, and judgement on the part of the public. Only when these three parties work together can hatred on the Internet be truly reduced.

Conclusion

The violence against innocent Japanese children is not only a personal tragedy, but also a mirror reflecting the long-standing backlog of hatred in cyberspace, the emotions amplified by algorithms, and the system’s and society’s indifference to the voice of reason. When hate speech in the name of “justice” to get approval, when the platform algorithm will be pushed to anger on the hot search, when the human voice instead of needing courage, we need to seriously reflect: a society’s digital environment has deviated from the proper track. Governance of online hate, not just a technical problem, but also a value problem. To avoid another tragedy, we must redefine what is tolerable expression and what is the true basis of consensus. Only when the system is no longer evasive, the platform is no longer permissive, and the public is no longer silent, will hatred lose its room to grow, and true humanity and rationality may be heard again.

References

Carlson, B. & Frazer, R. (2018) Social Media Mob: Being Indigenous Online. Sydney: Macquarie University. https://researchers.mq.edu.au/en/publications/social-media-mob-being-indigenous-online

Flew, Terry (2021) Hate Speech and Online Abuse. In Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity, pp. 91-96 (pp. 115-118 in some digital versions)

Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the internet: Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions that Shape Social Media. Yale University Press.

Jiang, Y. (2012). Cyber-Nationalism in China. https://doi.org/10.1017/9780987171894

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: the mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1293130

Massanari, Adrienne (2017) #Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures. New Media & Society, 19(3): 329–346.

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021, July 5). Facebook: Regulating hate speech in the Asia Pacific. Final Report to Facebook under the auspices of its Content Policy Research on Social Media Platforms Award. Dept of Media and Communication, University of Sydney and School of Political Science and International Studies, University of Queensland. https://r2pasiapacific.org/files/7099/2021_Facebook_hate_speech_Asia_report.pdfLinks to an external site.

Be the first to comment