(Picture: Google)

You may not realise that when you stayed up late last night watching short videos, there was an “invisible referee” scoring your life. It records whether you’ve parked in the right spot on a shared bike, how many times you’ve returned an online purchase, and even what articles you’ve retweeted on your social media. It ultimately determines whether you can qualify for a loan, rent an apartment, and travel abroad. In China, one such system affects the lives of hundreds of millions of people. Known as the “social credit system”, it uses artificial intelligence (AI) and big data to monitor and score individual behaviours, in a way that inversely “governs” society.

China’s social credit system: the combination of AI governance and social credit

(Picture: Google)

In China, the social credit system is becoming a new paradigm for digital governance, establishing a trust mechanism based on “credit” by recording and evaluating the behaviour of individuals and enterprises and with the progress and development of artificial intelligence (AI) and big data technology under the realization of large-scale, automated operation, reflecting a new algorithmic governance logic. Digital platform governance is no longer about legal or administrative control in the traditional sense, but more about guiding and disciplining behaviour through algorithms, code and platform architecture. (Flew, 2021)

From Credit Records to Behavioral Discipline: The Evolution of Social Credit Systems

The system’s objectives were initially very clear: to enhance financial transparency, encourage trustworthy behaviour, and combat “old liars.” It was first used in credit and other scenarios, such as whether a loan was paid on time and whether there was a record of court enforcement.

However, with the expansion of technological capabilities, the scope of coverage of this system has become broader and broader: whether to travel in a civilized manner, whether to pay the bill on time, and whether to post inappropriate comments on the Internet …… In the process, credit has changed from an “economic attribute” to a “social label”.

Key to this evolution is the ability of technology to “encode” social order – the role of AI in governance.

What role does AI play in the social credit system?

Crawford (2021) emphasizes in The Atlas of AI that AI is not a neutral technological tool, but rather an infrastructure embedded with politics, power, and social values. It not only executes instructions but also participates in the judgment of “defining what is normal and abnormal”. In China’s social credit system, AI has assumed just such a role.

The first is data integration and capture. AI can collect behavioural data about individuals from different platforms and sectors, including shopping records, travel trajectories, social discourse, legal records, and so on.

Next are behavioural analytics and pattern recognition. AI not only records what you do, but also models it through algorithms that predict what you might do, and this predictive analytics can directly impact credit scores. For example, a person who frequently changes his cell phone number or address may be flagged as a “risky user” even though he has not violated any laws.

Finally, automated decision-making and social stratification. Once the scoring system is linked to loans, rentals, and even educational resources, the AI’s “judgment” becomes a real-life ‘threshold’, and once labelled as a “bad faith”, it’s often very difficult to turn around.

Case study – The “old-liar” phenomenon: AI labelling of defaulters

(Picture: Google)

“Old-liar” are those individuals or enterprises who willfully fail to comply with court judgments and refuse to pay the sums or liabilities established in court judgments. In China, the courts will place an executor on a list of ‘bad faith executors’, commonly known as the ‘old-liar’ list, based on the executor’s breach of trust.

According to the 2023 Annual Report on Enforcement Work of Chinese Courts released by the Supreme People’s Court, the number of bad faith enforcers has continued to grow in recent years. By the end of 2023, courts nationwide had announced a cumulative total of 8.02 million defaulters.

Here’s an example of “Old-liar” that can help us better understand how AI governance works.

The Zhejiang Provincial Higher People’s Court has developed an artificial intelligence system called ‘Execution Brain’ in cooperation with Ant Group, Ali Cloud and other companies since 2019. The core objective of the system is to use AI and big data technology to identify and combat the concealment of property “old-liar”.

In 2021, the Hangzhou Intermediate People’s Court (Hangzhou Intermediate Court) discovered through its ‘Execution Brain’ AI system that Zhang, a defaulter, had evaded execution by concealing his property through improper means. Zhang hid his property in several ways:

- Virtual currency trading: Zhang used a virtual currency trading platform to transfer funds, attempting to conceal his property through the anonymity of virtual assets.

- Holding property through another person: Zhang registered the property in another person’s name to avoid seizure and execution by the court.

With the help of the ‘Execution Brain’ AI system, the court tracked down these behaviours and ultimately succeeded in recovering the 12 million yuan owed by Zhang.

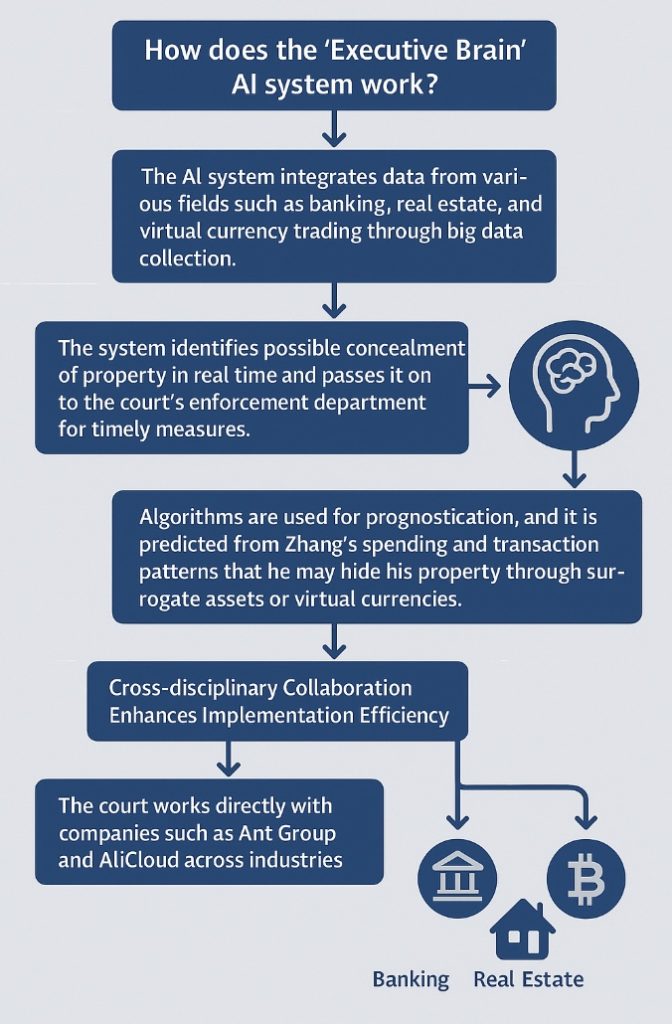

How does the ‘Executive Brain’ AI system work?

- Big Data Analytics and Prediction

The AI system integrates data from various fields such as banking, real estate, and virtual currency trading through big data collection. The system identifies possible concealment of property in real time and passes it on to the court’s enforcement department for timely measures. Algorithms were also used for prognostication, and by analysing Zhang’s spending and transaction patterns, it was predicted that he might hide his property through surrogate assets or virtual currencies.

- Cross-disciplinary collaboration enhances implementation efficiency

This case also demonstrates how AI can integrate resources. The court is able to work directly with companies such as Ant Group and AliCloud across industries and is able to access a large amount of data from a wide range of fields, including finance, real estate, and virtual currencies. This breaks down traditional industry boundaries, reduces court labour costs and time, and improves the accuracy and speed of enforcing judgements

(Generated by AI)

The key to AI governance: governor or control?

As Artificial Intelligence (AI) develops at a rapid pace, its role in social governance is becoming more complex. AI governance has raised controversies over privacy and technological ethics while enhancing judicial efficiency. Through an in-depth exploration of AI governance, we can’t help but ask: is AI a tool for ‘ governance’ or has it unwittingly become a means of controlling individual freedoms?

Boundaries of governance and control

In China’s social credit system, AI’s role seems to be to help the government better manage society by disciplining breaches of trust through behavioural monitoring and credit scoring. However, with the deep involvement of technology, the question has gradually surfaced: the role of AI in social governance, in the end, is to serve the public interest, or gradually become a ‘monitoring’ and ‘control’ of individual behaviour?

On the surface, AI governance looks like a ‘regulatory apparatus’ that monitors citizens’ behaviour in real-time to ensure that they comply with laws and social norms. However, the monitoring of such behaviour is often followed by potential infringements on individual freedoms. Some may question whether AI governance has gone beyond ‘governance’ and become a tool for ‘control’, limiting people’s right to privacy and autonomous decision-making.

The conflict between privacy and freedom

One of the most notable issues in AI governance is the conflict between privacy and freedom. When AI systems collect personal information through big data and use it to rate individual behaviour, is the individual’s right to privacy effectively safeguarded? Personal privacy should be respected and protected by the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) and the growing concern for privacy protection worldwide. In reality, however, these legal protections are often blurred in the face of AI and algorithms.

Under China’s social credit system, a person may be judged as ‘high risk’ because of frequent business trips or too many returns on purchases, which may have a direct impact on his or her credit score. Such data-based assessments, while seemingly ‘objective’, may exacerbate the oppression of individual freedoms and ignore the diversity behind individual behaviour.

Risks of technology misuse

While AI in social governance has demonstrated great potential, it also poses a non-negligible risk of misuse of the technology. As Kate Crawford (2021) reveals in The Atlas of AI, AI systems are essentially a ‘technological infrastructure embedded in historical power relations and social structures’ (p. 8). The algorithmic models behind AI systems are often not flawless and are not neutral tools; their design and execution are often subject to data bias, algorithmic bugs and even human manipulation.

If there is a lack of transparency in the collection and analysis of data in the social credit system, or if the data sources are inherently biased, then the judgements made by AI can lead to serious unfair consequences. This technological bias doesn’t just affect an individual’s credit score, it can also lead to group inequality, which in turn can exacerbate social divisions.

Finding the balance: how to optimise the use of AI governance in social credit systems

(Picture: Google)

As Artificial Intelligence (AI) becomes an increasingly important player in social governance, the question of how to balance technology with individual privacy, freedom, and fairness has become a key issue in current AI governance.

Privacy transparency and protection mechanisms

The first need is to introduce stricter data transparency mechanisms in the collection and use of AI data. Data transparency means that governments and relevant organisations should be open and clear about how they collect, store, use and share personal data. Citizens should know exactly what information will be collected and how this data will affect their credit scores and social behaviour. Transparency of data not only helps to increase citizens’ trust but also enhances the fairness of the system.

Second, privacy protection mechanisms must be more robust. This includes technical means such as data encryption, anonymisation and access control to ensure that personal information is not misused. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) enacted by the European Union provides an important reference for data protection globally, emphasising that all data processing activities must follow the principles of legality, fairness and transparency (European Union, 2016). The GDPR also introduces the principle of ‘data minimisation’, whereby only data that is directly relevant to credit scoring is collected, avoiding the over-collection and storage of unnecessary personal information. This not only reduces the risk of privacy breaches but also reduces the potential for data misuse.

Balancing control and freedom

Firstly, the boundaries of governance need to be clarified. The core objective of a social credit system should be to encourage trustworthy behaviours and reduce dishonest behaviours, rather than restricting the freedom of individuals through excessive behavioural monitoring, without the need to pay excessive attention to behaviours such as personal privacy or irrelevant behaviours (e.g. daily consumption habits).

At the same time, governance measures should be flexible. Credit scoring systems should be designed to be ‘people-centred’, introducing appropriate flexibility to respect individual diversity. For example, ratings of trustworthy behaviour could take into account contextual factors, rather than a broad-brush view of certain behaviours as ‘trustworthy’.

Finally, establishing robust grievance and feedback mechanisms and governance mechanisms must ensure that individuals have the right to be informed and to complain to avoid the injustices associated with opaque technological decisions (Wachter, 2017). Once an individual has been labelled as a ‘trustworthy’ person due to certain behaviours, he or she should be given ample opportunity to rebut or rectify the situation. Such a mechanism can, to a certain extent, circumvent the side effects of technological bias and safeguard the personal rights of individuals in the credit assessment system.

The future of AI governance: globalisation trends in social credit systems

(Picture: Google)

Now that AI governance has swept the globe, social credit systems may no longer be a governance tool ‘with Chinese characteristics’. More and more countries are exploring how to introduce AI technology into social management: from financial credit to public safety, from smart cities to individual behavioural scoring, AI is practically affecting the lives of all of us.

So, will other countries ‘learn’ from China’s social credit system model in the future? As it stands, some countries do invoke similar models for social governance.

- Singapore has introduced large-scale facial recognition and public behavioural surveillance systems as part of its ‘Smart Nation’ programme (Accenture, 2020; CBS News, 2021).

- Dubai, UAE, has launched the AI Governance City Index, which also uses a scoring system to quantify the ‘civic responsibility performance’ of city residents (U.AE, n.d.).

- In the EU, however, more emphasis is placed on ‘data protection’ and ‘individual freedom’. The EU’s draft Artificial Intelligence Bill (2021) explicitly prohibits the use of AI for ‘universal behavioural scoring’ systems, showing a striking difference from societies where collectivism is the cultural underpinning.

Therefore, a unified global AI governance model is almost impossible to achieve. What we will face in the future is a situation of ‘one technology, multiple governance logics’.

Conclusion

AI governance is a double-edged sword, acting as a catalyst for social development, but also potentially as a tool for power concentration and social control. The key to the future lies in how to grasp this ‘double-edged sword’ – we cannot ignore the potential risks of technology because of the convenience it brings, nor should we dismiss its positive value out of concern. By strengthening privacy transparency, safeguarding individual freedom, and improving the rule of law mechanism, we hope we can build an AI governance system that balances efficiency and fairness, technology and ethics.

AI governance is not a technical issue, but a social choice. How we design, use and regulate AI will determine the future direction of social governance.

Reference

Accenture. (2020). Singapore revolutionises national ID. [Case study].

https://www.accenture.com/ca-fr/case-studiesnew/public-service/singapore-revolutionises-national-id

CBS News. (2021, October 6). Singapore patrol robots stoke fears of surveillance state. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/singapore-robots-patrol-police-undesirable-behavior-robocop/

Crawford, K. (2021). The atlas of AI: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press.

European Union. (2016). General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). EUR-Lex. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj

European Union. (2021). Artificial Intelligence Act. https://artificialintelligenceact.eu/article/5/

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. Polity Press.

Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. (2021). Personal Information Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China. http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/c30834/202108/758b8fb62c2d4f1b9813e1e58b49d5d7.shtml

Supreme People’s Court of China. (2023). Annual report on Chinese court enforcement work. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2023-12/25/content_xxx.htm

UAE Government. (n.d.). Smart and sustainable cities. https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/digital-uae/digital-cities/smart-sustainable-cities

Wachter, S., Mittelstadt, B., & Floridi, L. (2017). Why a right to explanation of automated decision-making does not exist in the General Data Protection Regulation. International Data Privacy Law, 7(2), 76–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/idpl/ipx005

Zhejiang Daily. (2021). Hangzhou court’s “Execution Brain” solves the problem of dishonesty cases, recovering 12 million yuan. Zhejiang Daily. https://www.zjol.com.cn

Be the first to comment