What should platforms actually do when someone messes up on a livestream and the internet explodes? If the Li Meiyue situation tells us anything, it’s that they don’t really do much at all.

During a livestream in China with the American streamer IShowSpeed, Li Meiyue (hereafter referred to as Li) was helping translate. But things quickly spiraled. Li made a few comments—joking that local fans were acting like “animals,” asking if Speed wanted to find a “chick” in China, and misrepresenting a barber’s words about dreadlocks. It didn’t take long for social media to light up. Screenshots, reposts, hashtags—you name it. And while the backlash came fast, so did the views.

Li put out an apology video, saying it was all just a misunderstanding. Still, he reportedly lost over 200,000 followers within days. But here’s the twist: even as people called him out, the videos of his comments kept spreading. Not in spite of the backlash, but because of it. The algorithm saw people talking and pushed the content harder. And while Li’s PR took a hit, the platforms themselves scored big in attention.

This isn’t a one-off. We’ve seen it time and again: someone sparks outrage, the internet responds, and platforms rake in the clicks while staying totally silent. So it’s worth asking—why do they allow this cycle to continue? And what does it say about how they handle controversial or harmful moments?

What Actually Happened?

It’s also important to note the broader context of this livestream. Li has gained popularity for navigating East-West content online, often acting as a cultural bridge. But with that role comes responsibility—and scrutiny. When those watching perceive that someone is not representing a culture respectfully, the criticism hits harder. This isn’t just about one joke or one mistranslation; it’s about a pattern that some viewers have seen before, where Chinese voices or perspectives are sidelined or caricatured in front of a global audience.

While the incident itself might seem small to outsiders, to many viewers—especially those familiar with both Western and Chinese cultural codes—it felt like a tipping point. Li wasn’t just cracking awkward jokes; he was a cultural middleman, and the way he translated and framed interactions shaped how an international audience perceived China. This adds another layer to why the backlash was so intense. Viewers weren’t just reacting to the content—they were reacting to how it positioned Chinese people in a global spotlight.

Li wasn’t the main host of the stream. He was mostly there to translate and entertain. Even though his comments were made in English, they struck a nerve with Chinese viewers due to how they clashed with local cultural expectations. What sounds like casual slang in one language can feel downright disrespectful in another. Especially considering how he misrepresented a barber’s neutral comment. When a local barber, who couldn’t speak English, gestured that dreadlocks were difficult to style, Li translated it as the barber refusing to touch them because they were ‘too messy’—which many viewers saw as unnecessarily twisting the meaning.

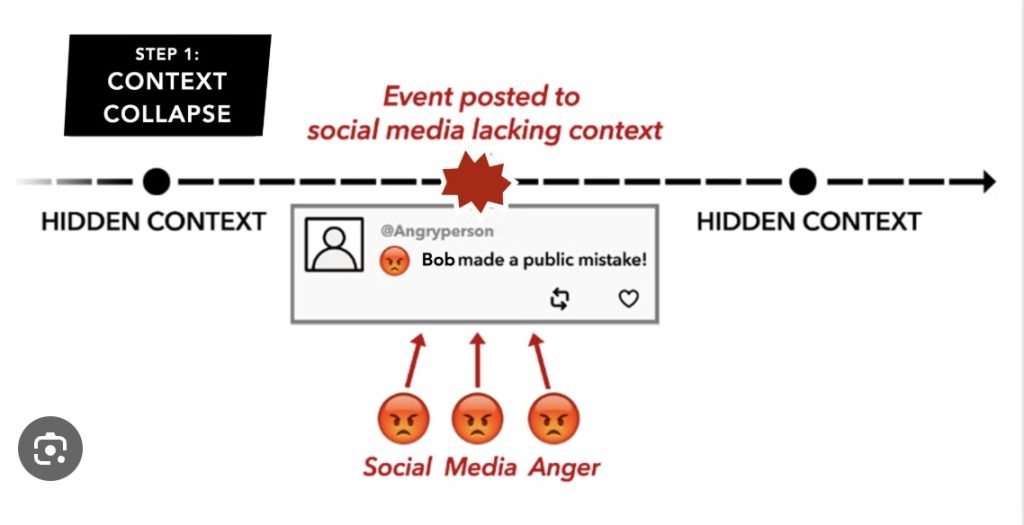

As soon as the clips started gaining traction, people started asking: why does content like this spread so easily? It wasn’t just about what Li said—it was about how quickly the internet picked it up, dissected it, and shared it everywhere. The conversation moved from criticizing Li to questioning the platforms themselves.

Some users began wondering: do these platforms even care? Did the algorithms push this stuff on purpose? Or is this just what happens when the only thing the system cares about is engagement? Either way, the result is the same: massive attention, zero accountability.

Why the Internet Keeps Amplifying Outrage

“Outrage is the most profitable emotion on the internet—and platforms have figured it out.”

Let’s face it: platforms like TikTok and YouTube aren’t in the business of nuance. They want your time and attention. And one of the fastest ways to get both? Drama.

Platforms are designed to “amplify that which grabs attention, regardless of whether the consequences… are good or bad” (Flew, 2021, p. 91). That means if something’s getting clicks—whether it’s funny, offensive, or just plain messy—it’s getting boosted.

So even after Li posted an apology, the content didn’t die down. It kept showing up in people’s feeds. Not because it deserved more attention, but because it was still getting reactions. And that’s all the algorithm needs.

And this goes way beyond one livestream. Every day, creators and users are rewarded for content that provokes—whether it’s a joke that lands poorly or a hot take that goes viral. The system isn’t broken. It’s working exactly as it was built: reward whatever gets the most engagement.

This turns online platforms into emotional slot machines. The more reactive the content, the bigger the payout. Over time, it changes how people behave online—and not necessarily for the better.

The Problem with Context-Free Moderation

It’s worth stepping back and asking: why haven’t we fixed this yet? Moderation isn’t new. The internet has been dealing with offensive or inappropriate content for decades. But what’s changed is the scale—and the stakes. Platforms now cater to billions of users across hundreds of cultures and languages. It’s no longer enough to have a global rulebook. What works in one country may completely miss the mark elsewhere. And yet, many companies still rely on generic policies instead of investing in truly localized strategies.

A big reason for this is cost. Training human moderators, paying for cultural consultants, and developing nuanced AI tools all require serious money. But when the goal is keeping users engaged—not necessarily safe—those investments often get pushed down the list. That leaves huge moderation blind spots, especially in regions outside North America and Europe. It’s not a coincidence that much of the research pointing out these failures comes from the Global South.

Now let’s talk moderation—or the lack of it. Whether or not something is offensive often depends on context: who said it, where they said it, how it was received (Anderson & Lepore, 2013). Global content policies are “usually created in English and translated afterward,” which leaves a lot of room for error (Sinpeng et al., 2021, p. 6).

In Li’s case, even though the comments were in English, the blowback happened in a Chinese cultural context. That difference matters. But platforms weren’t equipped to deal with it. According to the same study, companies like Facebook (and by extension, others) have consistently underinvested in moderation teams across Asia-Pacific (Sinpeng et al., 2021, p. 10).

That means moderators often aren’t fluent in local languages, or trained in cultural nuance. So content that’s obviously upsetting in one place might seem totally fine to someone judging it from another.

Even worse? Sometimes moderation systems punish the wrong people. Poorly designed moderation can end up silencing marginalized communities instead of protecting them (TrustLab, 2022). Automated filters often misread slang, tone, or dialects used by minority groups, flagging them unfairly.

So you get a double failure: harmful content that slips through the cracks, and real voices that get shut down. And once again, platforms avoid taking responsibility by blaming the “system.”

Why Didn’t the Platforms Take Action?

https://tapfiliate.com/blog/cancel-culture-influencer-marketing/)

In today’s platform playbook, silence isn’t an oversight—it’s a strategy.

This part really got to people. After all the backlash, Li’s still active. No ban, no suspension, not even a public statement from the platforms. Just… silence.

Most people weren’t asking for him to disappear. But they did expect some kind of response. And when none came, it looked like the platforms were just waiting for things to blow over—while they kept collecting clicks.

It’s not hard to see why. Engagement-based algorithms are great at surfacing divisive or emotional content—even when users say they don’t want it (Milli et al., 2023). Controversy keeps people glued to their screens, and the platforms profit off every second of it.

It all adds up to the same problem: moderation that’s out of touch, algorithms that reward outrage, and platforms that stay quiet until the storm passes.

Looking at the Bigger Picture

There’s another layer to this: the role of platform influence on public norms. Platforms don’t just reflect culture—they shape it. When creators like Li go viral for the wrong reasons and still face no real consequences, it sends a message to others. It teaches them what’s acceptable, or at least what they can get away with. Over time, that affects how people talk, what they joke about, and what kinds of content they feel empowered to share. It subtly reshapes the boundaries of public discourse, normalizing behaviors that would’ve once been flagged or criticized.

This is particularly worrying in an era when many users—especially young ones—get their news, entertainment, and community interactions from the same platforms. When controversy is rewarded and accountability is rare, users may internalize the idea that backlash equals success. That’s not a healthy online ecosystem. It’s one that thrives on provocation, not participation.

There’s also the issue of visibility. While some people like Li get dragged into the spotlight, others who are doing harm in quieter, less public ways often go unnoticed. This selective amplification means platforms are not only inconsistent, but reactive instead of proactive. They address problems when they blow up, not before. And that leaves marginalized communities to carry the burden of flagging bad behavior, often at their own emotional cost.

This kind of pattern isn’t accidental. Research shows that social learning in online networks tends to amplify certain moral violations while leaving others ignored—especially when they don’t provoke strong public outrage (Crockett, 2021). That makes the system not just reactive, but deeply selective.

Let’s also be honest—platforms aren’t just struggling to catch up. In many ways, they benefit from staying behind. Putting serious money into culturally informed moderation, building local teams, and actively intervening in controversial content isn’t cheap. Doing nothing, however, is free—and profitable. And that’s why these cycles repeat.

There’s also a growing sense of platform fatigue. Users are starting to recognize the pattern: outrage happens, nothing changes. We’ve seen it with influencers, political content, harmful trends—you name it. What used to spark real public outcry now just becomes another scrollable moment. That’s dangerous, because it numbs people to the very issues that deserve attention.

Li’s case isn’t just a social media slip-up. It’s a reminder that our platforms are built to prioritize what spreads, not what’s responsible. And when controversy becomes content, real people get hurt.

From Flew’s warning about the attention economy, to Sinpeng’s research on underfunded moderation in Asia, to TrustLab’s findings about algorithmic bias—the message is clear. The current system isn’t protecting users. It’s protecting engagement.

Until platforms start making decisions based on ethics rather than just traffic, we’ll keep seeing the same cycle: someone messes up, the internet explodes, and platforms sit back and count the clicks.

And those harmed by it? They’re left wondering why no one ever steps in.

Because on today’s internet, outrage isn’t a red flag—it’s a feature.

Moving Forward: What Needs to Change?

So, where do we go from here? If platforms want to rebuild trust and reduce harm, they have to stop pretending neutrality is an option. Silence may protect business in the short term, but in the long run, it chips away at user confidence. People aren’t just scrolling—they’re watching, remembering, and talking.

Public pressure can—and should—lead to better accountability. We’ve seen moments where community pushback forced companies to rethink policies, issue statements, and change course. But that kind of shift requires sustained attention, media literacy, and the willingness to call out the systems behind the slip-ups—not just the individuals caught in them.

This isn’t about cancel culture. It’s about asking for better: better standards, better enforcement, and better care for the diverse people who make these platforms what they are. Because without that, the internet will keep rewarding the wrong things—and failing the people who matter most.

Rreference:

Brady, W. J., McLoughlin, K., Doan, T. N., & Crockett, M. J. (2021). How social learning amplifies moral outrage expression in online social networks. Science Advances, 7(33). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abe5641

Flew, T. (2021). Hate speech and online abuse. In Regulating platforms (pp. 91–96). Polity Press.

Milli, S., Carroll, M., Wang, Y., Pandey, S., Zhao, S., & Dragan, A. D. (2025). Engagement, user satisfaction, and the amplification of divisive content on social media. PNAS Nexus, 4(3). https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgaf062

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021). Facebook: Regulating hate speech in the Asia Pacific (Report No. 2021-APAC-HS). R2P Asia Pacific. https://r2pasiapacific.org/files/7099/2021_Facebook_hate_speech_Asia_report.pdf

TrustLab. (2022, March 15). The impact of content moderation on marginalized communities [Blog post]. https://www.trustlab.com/post/the-impact-of-content-moderation-on-marginalized-communities

Be the first to comment