Violence in Twitch streams?

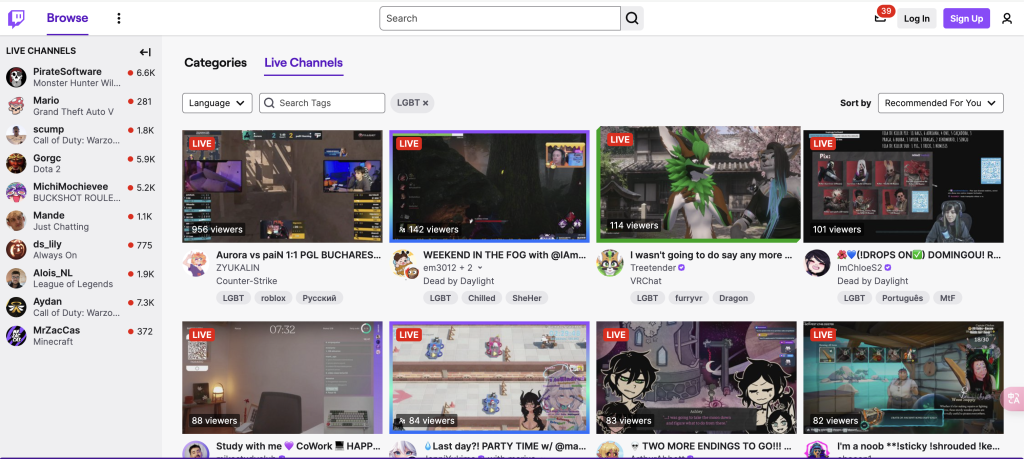

If you watch a lot of Twitch streams, you’ve probably seen the scene where an LGBTQ+ live streamer is happily interacting with viewers, and then suddenly the chat area is filled with ‘41%,’ ‘pervert,’ ‘get out,’ and other vicious comments. Seconds later, the studio was temporarily banned due to a ‘violation’ – not because the streamer had done anything wrong, but because someone had deliberately attacked them with hate speech and false reports.

This wasn’t just a random incident; it was a planned attack. Why has the world’s largest live-streaming gaming platform become a ‘digital battleground’ for the LGBTQ+ community? Is it just Twitch, or are other platforms facing a similar issue? What has been done to change this kind of situation? And what else can be done?

Most people think of the internet as an inclusive and friendly space, but the reality is disappointing: hate speech, online harms and moderation are always seen but rarely banned. In Regulating Platforms, it is mentioned that, in the United States, the Pew Research Centre reported that, in 2017, 41% of internet users claimed to have experienced online harassment, which in 18% of the cases was severe and included physical threats, harassment over a sustained period, sexual harassment, or stalking. Reasons for online harassment featured political or religious beliefs, physical appearance, race or ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation. Online harassment has evolved into hate speech on a large scale (Terry Flew,2021). Hate speech is eroding the health of the digital space.

Here are some examples.

Example 1: Snapscube, who is a non-binary, was playing the video game named ‘Among Us’ live on the internet when the chat area was flooded with ‘41%’. This number comes from a fact about the suicide rate of trans people, but people used it as an offensive taunt: ‘You’re in so much pain, why don’t you join the 41%?’ At first, Twitch’s AI review didn’t stop the messages because the system thought ‘41 percent’ was just a number, not a swear word. Then Twitch finally banned some accounts when people started complaining. Still, they didn’t do a good job of dealing with the problem.

Example 2: Keffals (Clara Sorrenti), a transgender streamer, was targeted in a hate speech raid on live stream. Attackers used robot accounts to swipe anti-trans comments such as ‘you are a man’ and ‘41%’. Sorrenti’s Twitch account was banned on 18 July 2022 for 28 days (later reduced to 14 days). This was because of ‘repeated use of hateful language or symbols’ on the cover of the stream. Sorrenti said that the so-called hate language was a screenshot of past harassment she had received, and that she had been banned for ‘talking publicly about the abuse she had received.’ Then, she even received real-life death threats and had to stop broadcasting for a while. Actually, the attack was not a random incident but organized. Keffals later found out that the people who planned it were from an anti-trans forum. This forum told people how to get around Twitch’s vetting system. Twitch updated its rules a few months later, adding ‘hate raiding’ to the list of things it was against.

Example 3: During a ‘valorant’ livestream, a group of gay live streamers were repeatedly subjected to insults and slurs during voice chat. Twitch, a live streaming platform, did not take prompt intervention. In another incident, during an ‘Among Us’ livestream, the streamers from the LGBTQ+ community faced voice harassment from players including death threats and sexualized insults. One player said: ‘I’ll kill the gay one first because he shouldn’t exist.’

Twitch’s ‘Struggle’: Did the update of the rules work?

In 2022, Twitch updated its policies about banning ‘Hate Raiding’. After the live streamers like Keffals protested, Twitch finally updated its policy to explicitly state that ‘hate raiding’ is a kind of violation, and at the same time tried to strengthen account verification and reduce robot attacks. The result is, this was initially effective, but soon attackers switched to small-scale harassment like slowly swiping with real accounts.

In 2023 came out the testing of the AI voice verification feature. Twitch started experimenting with real-time voice recognition AI, trying to catch in-game abuse. But here came the problem: Some comments were falsely blocked. For example, someone saying ‘kill the enemy’ was misclassified as ‘violent speech’. However, some hate speech in other languages went unpunished.

We can say that Twitch is improving, but it’s too slow and too full of bugs.

It is true that in today’s digital age, the LGBTQ+ community is facing a lot of hate speech and discrimination on social media, live streaming platforms and in online communities. This can be anything, from extreme speech on Twitter to real-time interactive harassment on Twitch, and from implicit censorship on Instagram to violent organizations on Telegram. The different platforms have governance gaps, which have allowed hateful content to spread and even evolve into real threats.

Why does hate speech always get past the censorship loophole?

Hate speech has been defined as speech that ‘expresses, encourages, stirs up, or incites hatred against a group of individuals distinguished by a particular feature or set of features such as race, ethnicity, gender, religion, nationality, and sexual orientation’ (Parekh, 2012) Moderation means that the platform reviews the content posted by users by manual or algorithmic means and decides whether to remove or restrict distribution. This does not sound like a difficult thing to do, but these definitions are actually ambiguous, resulting in platforms and governments often being caught in the dilemma of ‘what to regulate and how to regulate’. Social platforms such as Facebook, X, TikTok, process billions of pieces of content every day. They usually rely on AI auditing and then manual review, but there are still many problems.

Most of the main social platforms have introduced a range of policies to improve how they manage their platforms and deal with hate speech. This is to try to reduce the negative impact. But there are still some problems left to be solved.

Let’s take Facebook as an example.

According to Facebook: Regulating Hate Speech in the Asia Pacific, Facebook provided an outline of LGBTQ+ initiatives in the APAC region. It worked with the LGBTQ+ groups to protect the right of LGBTQ+ people; and to hear concerns and consult on platform and product policies. Facebook indicated that these consultations have led to concrete policy changes: for example, it now prohibits conversion therapy content that promotes claims to change or suppress one’s sexual orientation, or to suppress one’s gender identity. (Sinpeng, 2021). However, research reveals substantial implementation challenges. The one-size-fits-all approach of the platform does not take into account the linguistic nuances, the cultural contexts and the different legal frameworks in the APAC countries.

In investigating Facebook LGBTQ+ related pages in Myanmar, it was found that almost no one of the LGBTQ+ page administrators are aware of the community standards of Facebook regarding hate speech. Their hate speech monitoring training was provided by international third party organizations. According to the research, the preferred way to deal with hate speech is to deliberately leave such content shown on the page alone. Page administrators found that because the volume of unfiltered hate speech is so small, it is better to leave it on their pages for other members to see whenever it occurs. Often, members themselves have directly engaged with the content and attempted to remedy it with explanations that have not resulted in additional hate speech comments or replies.

On the contrary, according to the research, Australia has the strongest anti-discrimination protections for LGBTQ+ communities. Some, but not all of the anti-hate speech laws include incitement against sexuality, homosexuality and transgender as a basis for legal action. In addition, other areas of law can also protect LGBTQ+ communities from discrimination. For example, in 2017 the federal government amended marriage laws to achieve marriage equality for same sex couples. It can be said that Australia has a relatively robust legislative framework to prevent discrimination and hate speech. In 2020, Facebook established the Combatting Online Hate Advisory Group to fight against hate speech in Australia. It seems that whenever hate speech posted would be quickly removed by the site administrators of these large public accounts, given Australia’s relatively stronger speech protections for LGBTQ+ rights than other countries studied in the research. An administrator of the Mardi Gras Festival Facebook page said in an interview that they checked the page daily for offensive language, with alerts on their smart phone ‘all the time’. They used the site’s profanity filter, hiding comments when it gets too intense and blocking some accounts, although rarely for hate speech. They have reported posts to Facebook, although they forgot that it is in some way a satisfactory response. They said they followed the community’s guidelines and norms rather than trying to enforce the platform’s rules.

In countries like Myanmar, page administrators tended to leave hate speech alone, while Australian admins actively report, hide and remove hate speech. Besides, there are some commonalities across these region. Firstly, there is a disconnect between policy and enforcement. Although Facebook has worked with LGBTQ+ organizations in the Asia-Pacific region (APAC) and banned hate content, the actual vetting has been ineffective, with automated systems failing to identify new types of hate speech such as the ‘deprivation hate speech’ in the Philippines. Secondly, most of the audits are relied on user self-management. It is found that LGBTQ+ community administrators in the Philippines, Australia, and Myanmar have taken on a major role in cleaning up hate speech, but Facebook’s response mechanisms have been ineffective, with auto replies but no real action. Thirdly, regional laws can influence platform governance. The effect of Facebook’s audits is directly related to the strength of local legal protections, which can be learned from the difference between faster processing in Australia due to well-established laws, and lack of support in Myanmar.

It seems that Facebook’s rules about hate speech are not being used properly in Asia-Pacific. Facebook is not adapting to local realities, which creates dangerous gaps in governance that mostly affect marginalized communities.

So, what are the main issues that have led to this situation? What can be done?

The technology is limited. AI review systems often have trouble understanding cultural context such as different languages or special spellings. They also don’t effectively monitor real-time content like live streaming, voice and so on.

The rules on the platforms are confusing and contradictory. The platforms’ commercial interests like advertising are sometimes prioritized over user safety. They rely too much on automation, which sometimes blocks LGBTQ+ related contents or misses hate speech.

There are gaps in laws and enforcement in different parts of the world. Some countries don’t have specific laws to deal with hate speech and online harms. Platforms sometimes compromise in conservative areas. For example, YouTube restricts streaming of LGBTQ+ supportive videos to comply with local regulations.

Facing the above problems, it seems urgent to find ways to balance the inclusive online space with reducing the negative impact of hate speech.

In response to the first issue, upgrading technology seems important. We can develop AI that understands local slurs like the culturally specific hate speech in the Philippines. Pop-up warnings such as ‘This may be hurtful’ can be displayed before posting, and there should be punishment according to severity. There can be warnings for mild insults or bans for violent threats. About the governance of the platform, policy improvements should be taken. For example, it will be better if governments can adapt hate speech rules for different countries. Besides this, we can form local oversight groups with LGBTQ+ representatives. These groups can do many things to clean up the online environment. They can prioritize extreme cases such as death threats for review within 24 hours, and they can publish quarterly reports showing how many hate posts were removed, the average response time and the success rates of user appeals. Users can have the right to choose whether to delete or hide flagged content and to view safety reports for their networks. This is important because transparency is vital. Researchers can be allowed to study moderation data and there should be independent audits of platforms’ systems. We can give group administrators dashboards to track harmful content, so that some of the specific offensive words and phrases can be blocked.

To make more people aware of this situation, working together to solve these problems, offering training programs is a good method. Through training programs, we can train community leaders to deal with online abuse and create emergency response guides for sudden spikes in hate speech. Besides, legal advocacy may be effective. Pushing for stronger anti-harassment laws in Asia seems beneficial, and it is necessary to balance freedom of expression with protection for marginalized groups.

Conclusion

Cyberspace should be a place where everyone is welcome and safe, but the current way that platforms are governed still puts the LGBTQ+ community at a disadvantage. To solve this problem, we need to make a lot of different changes. These include new technology, changes to the rules, getting the community involved, and legal protections. Platforms should put user safety before making money. Then the internet can be a place where everyone, no matter their sexual orientation or gender identity, can express themselves freely.

Reference List

Flew, T. (2021) ‘Issues of Concern’, in Regulating Platforms. Cambridge, UK: Polity, pp.115.

Parekh, B. (2012). Is there a case for banning hate speech? In M. Herz and P. Molnar (eds), The Content and Context of Hate Speech: Rethinking Regulation and Responses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, (pp. 40).

Sinpeng, A. (2021). Facebook: Regulating Hate Speech in the Asia Pacific.(pp.22)

Asia-Pacific Regional Forum (APRF), 2020. Integrated Asia-Pacific Recommendations: Asia-Pacific Regional Forum on “Hate Speech, Social Media and Minorities”, October 19-20, 2020. Minority Forum Info. https://www.minorityforum.info/page/asia-pacific-regional-forum-on-hate-speech-social-media-and-minorities

Gach, E. (2022, July 21). Banned Her For ‘Openly Talking’ About Abuse She Receives. Kotaku. https://kotaku.com/twitch-ban-keffals-destiny-trans-hate-speech-slur-1849315462

Blake, V. (2024, Nov.5). Twitch streams about “political and sensitive issues” including “reproductive and LGBTQ+ rights” now require a label. Eurogamer. https://www.eurogamer.net/twitch-streams-about-political-and-sensitive-issues-including-reproductive-and-lgbtq-rights-now-require-a-label

Be the first to comment