Now, in the digital era, online hate speech has become a global cause of concern. A 2023 UNESCO/Ipsos survey indicated that 67% of internet users in 16 countries reported experiencing online hate speech, with 85% of them being concerned with its social impacts (UNESCO&Ipsos, 2023). According to the eSafety Commissioner’s 2025 report, drawn from a nationally representative survey of over 5,000 adults interviewed in November 2022, 18% of adults had personally experienced online hate speech in the last 12 months. It was even higher at 24% in targeted communities—those who are sex-diverse, those with disability, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples (eSafety Commissioner, 2025).

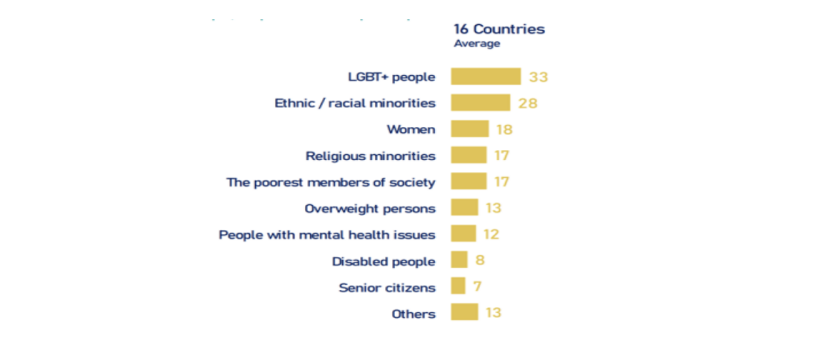

Biggest victims of hate speech on social media across 16 countries were LGBT+ people (33%), ethnic/ racial minorities (28%), women (18%), religious minorities (17%), the poorest members of society (17%), overweight persons (13%), people with mental health issues (12%) etc.

Despite known links to real-world violence, most platforms still fail to moderate hate speech effectively. We will examine the nature of online hate speech in greater depth, discuss the underlying cultural dynamics that drive such a phenomenon, and critically review the effectiveness of contemporary platform regulation in combating such issues.

How Hate Speech Functions as a Tool of Marginalisation

Online hate speech is not merely a matter of offensive or objectionable language—rather, it is a particular type of damaging expression that targets a person because of their group membership or their personal identity. Hateful speeches need to be considered as speech that can harm immediately and over time,” as well as one which “discriminates against people on the basis of their perceived membership of a group that is marginalised” in a specific social setting (Sinpeng et al., 2021, p. 6). In contrast to offensive speech, however, which may offend, online hate speech is legally and morally actionable because it reinforces and reduplicates structural inequalities.

Scholars then subdivide the harms that accrue on account of hate speech into two types: causal and constitutive. Causal harm involves practical effects like heightening prejudices, discrimination, or incitement of violence—effects that are contingent on exposure to hate speech. Constitutive harm, by contrast, accrues on account of the fact that such words are uttered at all; it comprises acts of subordination, humiliations, and symbolic exclusions that reaffirm societies’ hierarchies as well as deny marginalised parties a place equal to others in the public sphere (Sinpeng et al., 2021, pp. 6–7).

Labeling women as ‘inferior’ or immigrants as ‘insects’ dehumanises them and justifies exclusion. Because of this, we understand hate speech not as a personal affront, but as a “discursive act of discrimination” that plays a part in structural patterns of oppression (Sinpeng et al., 2021, p. 6). The former aims at, or has the effect of, oppressing marginalised groups, whereas the latter may provoke offence, challenge, or merely annoy, but has no subjugating power.

Therefore, platform and policy moderation needs to get beyond surface-level offence to confront the structural and contextual elements of hate speech—something that the platforms like Facebook, by the findings, tends not to do on a regular basis (Sinpeng et al., 2021, pp. 5–7). Online hate is, quite simply, more than a matter of words; it is a system of harm built into vocabulary, magnified by digital media reach, and naturalised by a tolerant culture.

Trolls, Memes, and ‘Just Joking’: When Harassment Becomes Culture

Online hate speech isn’t always delivered as open slurs or threats. It can be packed in irony, memes, as well as performative internet troll banter. Reddit, a site self-described as a forum for free expression, has become a powerful case study in how certain forms of online harassment are legitimised through platform design, algorithmic culture, and a highly gendered user base. Scholars refer to such spaces as “toxic technocultures”—digital spaces of interaction where hate speech as well as concerted harassments aren’t just tolerated, but promoted (Massanari, 2017).

Moderation frameworks often reflect biased platform values. Posts that conform to dominant (often white male) users are promoted by being upvoted and highlighted; those that seem contrarian, especially the postings of women and users of colour, get downvoted or trolled into silence (Massanari, 2017).

This performative trolling ethos was evident full force during the 2014 #Gamergate campaign. In the guise of a campaign promoting “ethics in games journalism,” participants organised a mass harassment campaign targeting feminist women such as Zoe Quinn and Anita Sarkeisan. Many were doxed, threatened with sexual assault, and driven underground. The ease of creating subreddits, the reluctance of the platform to delete offending content, and a karma-based system of rewards on Reddit helped Gamergate go viral. Subreddits like /r/KotakuInAction masked abuse as political discourse (Massanari, 2017).

The primary risk is how that behaviour becomes normalised. According to Massanari (2017), not only does the structure of Reddit accommodate toxic speech, it actually amplifies it by systematically promoting popular (i.e., conformist) content and limiting recourse for victims of abuse (Massanari, 2017). This has a chilling impact where those most at risk from hate speech are forced offline, with those conducting it becoming emboldened by platform inertia.

Ignored and Exhausted: Facebook’s Failures in the Asia-Pacific LGBTQ+ Community

Although Facebook claims it is a global leader when it comes to moderation of hate speech, its approach in the Asia-Pacific region – particularly towards LGBTQ+ communities – demonstrates extreme differences between policy and practice. A 2021 regional study conveyed that LGBTQ+ users across the Asia-Pacific region, regularly received hate speech addressed at or directed towards them, which either fell beyond Facebook’s narrow definitions of policy or never removed, despite being reported, causing the user feeling disempowered and distrustful in the moderation processes (Sinpeng et al.2021, pp. 4-5).

Being LGBTI in Asia and the Pacific | United Nations Development Programme

The researchers undertook a series of interviews with administrators of LGBTQ+ group pages from Myanmar, Indonesia, and the Philippines. Volunteer moderators, with no formal training, reported persistent targeting. Even more worryingly, moderators who flagged such hateful content through their reporting tools would note, “it went nowhere,” and then fostered what was described as “reporting fatigue” (Sinpeng et al., 2021, p. 40).

In Myanmar, lacking LGBTQ+ legal protections, moderators often left posts active due to fear of escalation. For Indonesia and the Philippines, there were reports that Facebook’s automated filters for ongoing moderation would often fail to identify or detect hate speech when it was written in dialect or culturally specific bigotry expressions. In the absence of the administered local dialects/languages, the contents were left unattended (Sinpeng et al., 2021, pp. 34-35).

Many admins also shared that even if hateful posts were successfully flagged or removed, those posts would reappear again on the original or other community page sometimes facilitated by the same user. When the non-removal of post publications happened, other admins communicated the privacy in which reporting or appeal process was convoluted and were disappointed or dissatisfied in the process when content criticisms were similar in violation towards themselves other Tier 1 hate speech content moderation standards.

What the experiences represent is not merely an enforcement issue, but more a broader structural neglect of marginal voices in a non-Western context. Facebook’s content regulation in the Asia-Pacific are still inadequate in language, cultural sensitivity, or engagement with their local community or populations and without concerting reforms including hate speech moderation in local languages, and trust networks made public to engage users and the community to monitor, the vision for all users in Facebook’s “safe community” will remain deeply unequal.

Platforms on the Edge: Self-Regulation or Systemic Evasion?

Platforms often invoke free speech to justify moderation inaction. While major platforms like Facebook claim to operate a globally-informed, locally responsive moderation system, their practices betray a lack of a complex system. Inside the platform, Facebook outsources a substantial portion of its moderation labour to third-party contractors under a system where poorly-paid contractors manage high cognitive loads, language barriers and video and photo rules (Roberts, 2019, pp. 34–35). Then for the publishing user, reporting hate speech usually receives a wild response or nothing, or worse—the user sees published hate speech as being temporarily flagged and then reinstated without explanation (Sinpeng et al., 2021, p. 4).

Roberts (2019) notes that pre-screening content is rare; most harmful content now goes unchecked until after the post, giving hate speech and disinformation time to circulate unregulated until an intervention is sanctioned (Roberts, 2019, pp. 35–37).

For example, during the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar, Facebook received significant criticism from human rights groups and the UN for inaction on growing online hate speech that resulted in violence. Facebook then put together a comprehensive Burmese translation for Myanmar and improved its detection of hate speech in minority languages (UN IIMM, as cited in Sinpeng et al., 2021, p.35).

Despite their resources, platforms still see moderation as an afterthought. This ongoing failure of action—disguised in neutrality shade—has allowed online hate speech to flourish, while the platforms are profiting from user engagement. Without looking to a stronger regulatory framework, the responsibility falls unfairly to users and civil society to clean up the mess.

AI, Human Moderators, and the Limits of Technology

As attempts to combat hate speech continue to grow on the Internet, more and more platforms have begun to utilize artificial intelligence (AI) in order to identify and decrease harmful content. Although AI is useful for strategic scale, it often falls short of understanding the nuances when analyzing context, the use of irony, and changing slang, which can lead to false positives and negatives in its response. Human moderators are vital where AI fails.

Federal Reserve Governor Lisa D. Cook speaks at the Economic Club of New York in New York City, U.S., June 25, 2024. REUTERS/Shannon Stapleton

A vivid example of the flaws of the moderation systems currently employed occurred in April 2025, during a live-streamed speech by Federal Reserve Governor Lisa Cook, which was held at the University of Pittsburgh. The video feed was hacked by a group that inserted racist comments, Nazi symbols, and pornographic images into the feed. The event was in-person and went on as always, but the online event had to cut the Q&A portion because of the disruption from the feed. This incident demonstrates the challenges of real-time moderation (Reuters, 2025).

Rethinking Regulation: Local Expertise, Human Moderators & Real Accountability

Curbing online hate speech cannot—and should not—be left to platforms alone. Such a multifaceted issue necessitates a multi-stakeholder governance modality that extends beyond corporate commitments and upholds accountability from a wide range actors—tech firms, civil society, regulators, and users too. “Although platforms have the technical capacity, without third-party pressure or oversight, meaningful change remains unlikely.”

One positive means to make progress in this regard is through the enlargement and formalisation of stakeholder engagement mechanisms, incorporating stakeholders from civil society organisations (CSOs), academia, journalism, and community groups. For example, Facebook’s stakeholder engagement team in the Asia Pacific region is involved with the input of multiple stakeholders to attempt to reconcile definitions of hate speech, which can be contested notions that differ by cultural and legal context. The lack of transparency over stakeholder identities and impact remains a concern (Sinpeng et al., 2021, p. 22).

In a similar vein, the Trusted Partner programme on Facebook, which was originally designed in response to Facebook’s role in the Myanmar crisis, was intended as a direct channel for civil society organisations (CSOs) to escalate or report cases of hate speech. In practice, however, the criteria for eligibility, lack of advertising, and low transparency around its functions meant that across numerous Asia-Pacific states no partners were declared in country, meaning there were no rapid-response mechanisms when digital attacks took place and vulnerable communities were left without protection (Sinpeng et al., 2021, p. 21).

As Sinpeng et al. (2021) describe, “the task of combating hate speech online is now a collaborative project, which involves corporate, civil society and government actors in various internet governance arrangements” (Sinpeng et al., 2021, p. 3).Platforms must rebuild trust through transparency, clearer moderation guidelines, and open stakeholder collaboration.

Conclusion

To say online hate speech is a digital rant is an understatement; it is part of a systemic problem that echoes into the real world. From Reddit’s toxicity to Facebook’s LGBTQ+ failures, the impacts are clear. Platforms are not neutral; they actively shape online harm. Despite vast resources, platforms still prioritise engagement over safety. Systemic change requires shared responsibility and continued public pressure. The future of digital spaces depends not just on whether we act, but how urgently and collectively we respond.

References

eSafety Commissioner. (2025). Fighting the tide: Encounters with online hate among targeted groups.

Ipsos. (2023). Survey on the impact of online disinformation and hate speech. UNESCO. https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2023-11/unesco-ipsos-online-disinformation-hate-speech.pdf

Massanari, A. (2017). #Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures. New Media & Society, 19(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815608807

Reuters. (2025, April 3). Online feed event with Fed’s Cook hit with porn, Nazi images. Reuters.

Roberts, S. T. (2019). Behind the screen: Content moderation in the shadows of social media (pp. 33–72). Yale University Press.

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021, July 5). Facebook: Regulating hate speech in the Asia Pacific (Final report). University of Sydney & University of Queensland.

Be the first to comment