When was the last time you read a privacy policy carefully?

Probably never. Especially when people open a fun app like TikTok, who would read the thousands of words of terms and agreements when registering? But at the moment of clicking “I agree”, we may quietly hand over the use of private data.

In the digital age, control seems to be in our hands, but this is just an illusion created by the platform. What we should pay attention to is not who owns the platform, not the “promise” of the platform, but whether we really have control over our own privacy.

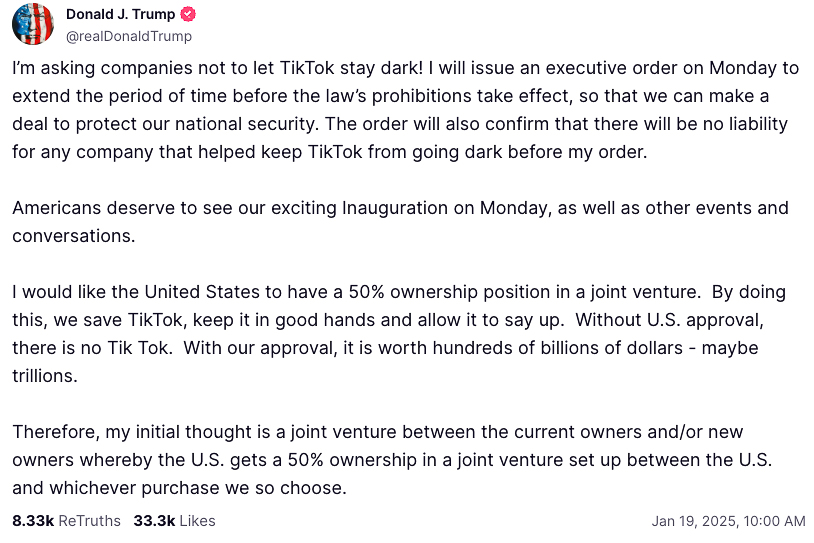

On January 19, 2025, TikTok was banned in the United States because the US government believed that TikTok was suspected of illegally collecting and using user data and there might be huge privacy and digital security issues. However, just 12 hours after the ban was issued, the ban was lifted with the intervention of President Trump, and TikTok resumed its services, and stated that the US investor might hold a 50% stake in the TikTok joint venture. Interestingly, even though the US government has been emphasizing the privacy issues it brings, it was still widely opposed when the ban was issued, especially among young people in the United States. This dramatic scene actually reflects several issues about privacy and digital rights: In the practice of privacy protection, does it matter who controls the platform? Why are people willing to “trade privacy for happiness”? Does the platform really give us the power to control privacy?

Does it matter who controls the platform?

In the above incidents, the US government strengthened the protection of user privacy and security through legal and capital intervention in Tik Tok. Although this solves some problems about TikTok’s national data security, it is still difficult to solve the fundamental problem of user privacy. Because this measure only changes “who controls the platform” rather than enhancing the power of users to control their own private data. In other words, this is a political means of responding to public anxiety through structural adjustments, rather than strengthening the digital rights of platform users. Users still find it difficult to choose whether their data can be collected, stored, analyzed or used for other commercial and political purposes.

It is worth noting that after the ban was lifted, the US government did not promote a substantive and systematic user data protection bill for TikTok, and TikTok’s user data collection mechanism, business mechanism, and algorithm model were not changed. If the Tik Tok joint venture is 50% owned by American investors, then only part of the control of the platform will be changed. Therefore, we should think about whether this change can really solve the concerns of citizens about privacy and data security? Is the new capital improving the privacy protection mechanism from the user’s perspective, or is it simply changing the beneficiaries of commercial interests? Obviously, what we should care most about is not who has the dominant power to manage the platform, but whether we have the dominant power over our own private data.

If a platform’s collection and use of user data is still imperceptible, mandatory, and vague regardless of who controls it, it means that we still lack privacy protection and digital rights when using this platform. On the contrary, if a platform’s data collection logic is clear and open, and can be decided by users themselves, then it respects users’ digital rights more than most “compliant platforms”. In the digital age, digital rights as part of human rights have become an important topic of political and academic debate, and a new order needs to be established to address public concerns (Karppinen, 2017).

A truly effective user privacy protection plan should not only focus on who controls the digital platform, but should focus on the user’s actual use process and experience. Simply put, it should make people truly feel that “I decide whether my private data can be used and how it can be used.” For example, users can quickly and clearly know what they have authorized when registering, can freely adjust privacy preferences at any time, and can completely delete their data when exiting the platform. These specific and easily perceived links are the standards for testing whether the platform is truly centered on user privacy. However, these simple wishes actually require the joint efforts and exploration of governments, enterprises, and individuals to be realized.

Why are people willing to “trade privacy for happiness”?

Although there have been many criticisms of TikTok’s data collection and use behavior, it still has a huge user base of nearly 1.1 billion worldwide, especially among young people. It is a mainstream platform. So why are people willing to sacrifice privacy in exchange for user experience?

One of the obvious reasons is that its algorithmic logic makes users addicted. By analyzing user data, the content it recommends is highly personalized and the feedback is immediate, which greatly optimizes people’s user experience. In other words, people can clearly feel that “the platform understands me very well and always gives me the content I want.” Moreover, its behavior manipulation ability is actually far beyond our daily cognition. It repeatedly stimulates people’s senses through the algorithm push mechanism, and users form usage habits and even become dependent in this process. This is an attention economy, which means that all our data and browsing and usage behaviors will be converted into commercial interests, such as accurately pushing advertisements based on how often users click on specific content (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [ACCC], 2021). The platform will do everything it can to make people dependent on it. It is difficult for people to realize that privacy has become the price of their every use behavior when they are immersed in it.

Another important reason is people’s numbness to privacy and security. In today’s digital age, facing the continuous emergence of data leaks, the public is gradually tired of digital privacy and data security issues. TikTok’s problems are not a special case, but a microcosm of the broader privacy crisis. Some people even think that since privacy cannot be protected, they should ignore it and immerse themselves in the entertainment provided by the platform. Instead of resisting, it is better to get rewards. This submissive mentality is extremely dangerous. If everyone maintains this attitude, the platform can continue to expand its right to use user privacy in an environment without effective supervision, and we unknowingly give up the digital rights we should have.

In addition, compared with the security risks in real life, the risks and consequences of privacy loss are often invisible and lagging. This has led to many people lacking a sense of crisis about privacy and digital security issues. For example, we clearly know the consequences of crossing the road, but it is difficult to know what specific harm our “stolen privacy” on the platform will cause us. In many cases, we are not even aware of this harm. But not being aware does not mean that it will not happen. People always wait until the crisis comes to truly realize its horror.

In fact, we are not born not caring about digital privacy, but the platform’s addictive mechanism, the cost of privacy leakage is difficult to perceive, the lack of a comprehensive regulatory environment, the lack of digital rights education and other factors have continuously weakened people’s privacy protection awareness and rights. Privacy leakage, abuse of personal data and other issues have caused widespread concern around the world (Flew, 2019). To change this situation, it is far from enough to rely on individuals alone. The entire social mechanism is needed to empower users and shape the common value concept of “privacy data belongs to users”.

Does the platform really give us the power to control privacy?

Almost every platform claims that they protect user privacy, but how to protect, how to supervise, where the data will be used, and how long to keep it are all difficult to clearly verify. At the same time, the platform will provide users with a series of privacy settings options, as if we can control where the data goes. But is it really so? Actually not, because most people do not fully understand the platform’s collection and use of private data, and at the same time, many designs of the platform also make this process obscure and hidden.

First of all, taking the interface design of Tik Tok as an example, most of the privacy settings are in the complex settings menu and involve some professional terms. As an ordinary person, it is almost impossible to really understand every setting. Sometimes people can’t even find the menu where the privacy settings they want to change are. It’s like hiding the key and then telling you that you can use the key to open the door at any time. Moreover, many people still do not have a sense of control over the data after setting the privacy settings (Goggin, 2017). The platform may still obtain and analyze the user’s private data through background tracking and other methods.

It is worth noting that the platform will use a design to “legalize” its data collection and use behavior, which is the privacy terms mentioned at the beginning of the article. For example, to register a Tik Tok account and use the platform’s functions, you first need to click to agree to all the terms of the platform, otherwise you will not be able to use it normally. This makes users face a 2-choice situation, either agree or give up using the platform. In fact, most people will directly click “Agree” without really reading the thousands of words of privacy terms (after all, even if they read it, they can’t understand a lot of professional terms), let alone give up using it directly. This design of the platform guides users to agree to some data collection behaviors by default. This step alone legalizes large-scale information collection and turns it into “users agree to provide data.” But we don’t actually understand what we specifically agree to.

Therefore, “voluntarily providing data” is a lie and the price we have to pay for using these platforms. On the surface, we have the power of choice and control over our privacy data, but in fact we have just fallen into a carefully designed trap.

Nowadays, our lives are very dependent on various data platforms, such as reading news, chatting, shopping, learning and so on. Therefore, we are not only users and consumers, but also inevitably become objects of observation and analysis. Our privacy data has become an “add-on” to our participation in contemporary life (Marwick & boyd, 2018). Perhaps some people think that exchanging privacy data for platform experience is not a major problem, which underestimates the influence of these data platforms. The good experience they provide makes many people only see its advantages, but reduce their sensitivity to privacy issues. If we do not re-examine the power relationship between users and platforms, privacy issues will only become more and more serious in the future.

Let privacy return to the hands of users

The protection of privacy rights is not about who controls the platform, nor is it a few options in the privacy settings, nor is it the “promise” made by the platform. It should be user-centric, protect the user’s right to know and right to choose, establish an effective regulatory mechanism, and jointly protect the digital order by the government, platforms, and the public, so that everyone can be the master of their own privacy. Otherwise, our privacy will only gradually and completely disappear in one compromise after another.

Please don’t forget that we have the right to say “no”. We don’t need to be technical experts, nor do we need to memorize every privacy clause. We just need to have the power and opportunity to say “no”. When privacy rights are truly returned to users, digital life will no longer be just observed and calculated, but a space that can be chosen and controlled. That is a truly free future worth fighting for together.

Reference List

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. (2021). Digital advertising services inquiry Final report (ACCC 08/21_21-58, pp. 1–197). Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. https://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/Digital%20advertising%20services%20inquiry%20-%20final%20report.pdf

Flew T. (2019). Platforms on Trial. Intermedia, 46(2), 18–23. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/120461/

Goggin, G. (2017). Digital Rights in Australia. The University of Sydney. https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/17587

Karppinen, K. (2017). Human rights and the digital. In H. Tumber & S. Waisbord (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Media and Human Rights (pp. 95–103). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315619835

Marwick, A. E., & Boyd, D. (2018). Understanding Privacy at the Margins: Introduction. International Journal of Communication, 12, 1157–1165.

Be the first to comment