“Mark Zuckerberg F8 2018 Keynote” by Anthony Quintano CC BY 2.0

Early proponents of the internet conceived of a virtual mega-space free from government leash and control. Prevailing debates of the time described a perfect canvas where every Joe, Mei, and Amina could belong and participate, hold and express thoughts, and trade relationships without hindrance (Flew, 2022).

In his famous espousal, “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” American essayist and cyberlibertarian activist, John Perry Barlow, markedly shooed any ideas of external governance because from “ethics, enlightened self-interest, and the commonweal, our governance (of the internet) will emerge.” It was the libertarian internet (Flew, 2022), one characterised by openness, freedom of thoughts and transactions, and spontaneous ordering.

These libertarian ideas would go on to define internet culture and governance for many years. When, in 1996, the United States Congress enacted a suite of measures known as the Communications Decency Act (CDA) to regulate ‘indecent’ and ‘obscene’ content on the internet in the interest of minors, it took just a year for the Supreme Court to void them as unconstitutional and anti-free speech. Also, in what seemed like an echo of Barlow’s declaration, the Court ruled that the Internet is unique and that the Decency Act did not have the legal fortitude to regulate its content.

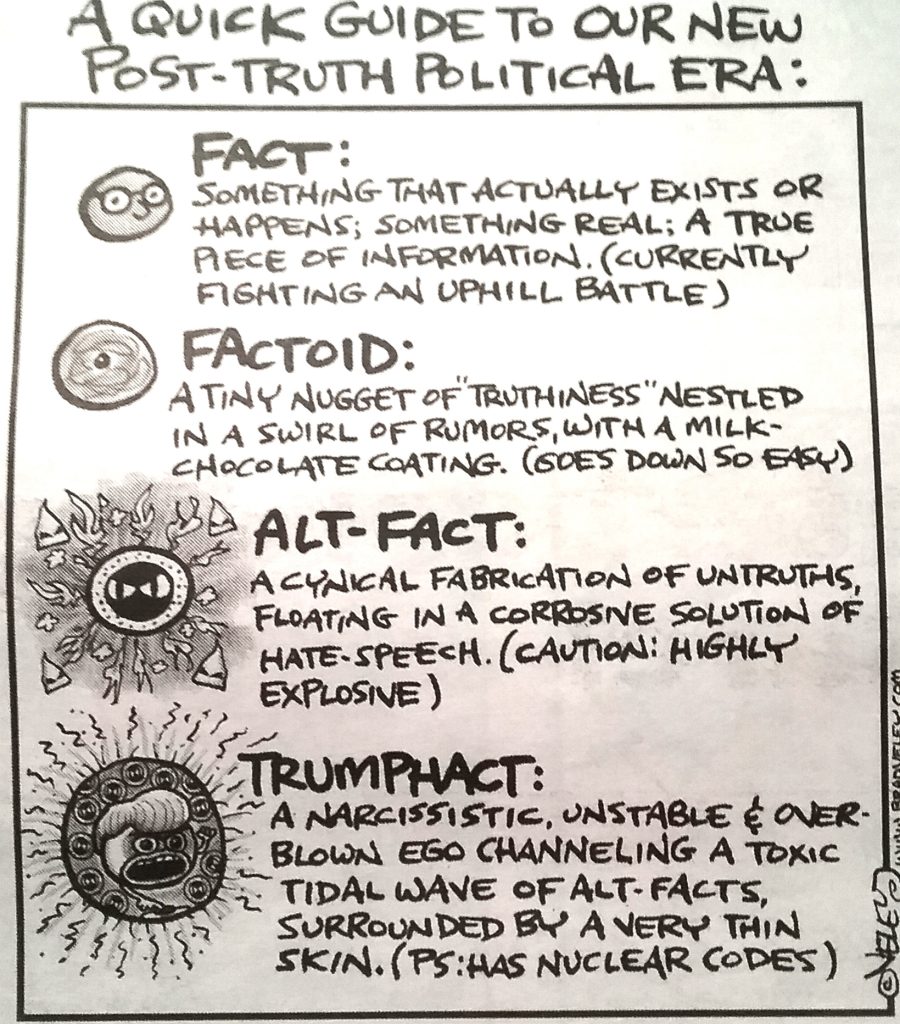

The very concept of objective truth is fading out of the world. Lies will pass into history.

– George Orwell–

“Cartoon–Politics–A quick guide to our new post-truth political era. Fact: Something that actually exists or happens; something real; a true piece of information.” by LittleRoamingChief is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

In recent times, however, many events have called into question the place of truth in the content-driven landscape of the internet, and with the popularity of populist politics that attacks established arbiters of facts, what’s the fate of the world? Free expression and a degenerate society or moderation that keeps society healthy?

Social Platforms and Content Democratisation

After about fifteen years of the Internet as an open cyberspace for all, access and participation increasingly began to be facilitated by digital intermediaries or platforms. This meant that, unlike the early practice of wandering the wilderness of the internet for individual services, users began to access aggregated services such as information search, relationship and community building, and content creation through dedicated platforms that provide the needed affordances for such, and at scale (Srnicek, 2017).

With the rise of platforms and the proliferation of content, the libertarian ideas of the early internet and the safe harbour principles that remained of the Decency Act became the favourite invocation of platforms. According to Srnicek (2017), platforms thrive on positive network effects, meaning the more (users and content on a platform), the merrier (for the platform), and such effect is factored by scale of exchange or what you might call traffic and ease of use.

It is convenient for platforms to say, “hands off us, governments, and do not hold us to account for whatever goes on our platforms. We are mere conduits and there is free speech.” In his speech about the importance of free expression at Georgetown University in 2019, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg said he believed people (users), and not tech companies should be the arbiter of truth. Narratives such as this, even while illusionary, are promoted by platforms to ‘avoid legal and cultural responsibility’ (Gillespie, 2018).

In truth, however, platforms must moderate users’ content and, broadly, activities to remain a desired choice for their users and advertisers. Brands do not want to advertise on a platform where antisocial content can latch onto their ads, and user experience is damaged where abuse and disinformation persist (Gillespie, 2018).

Since the maturity of Web 2.0, amplified by platforms with affordances for interactivity, social networking, and user-created content, the internet has been faced with a myriad of reimagined challenges at an unprecedented scope– from privacy and data mining to intellectual theft, deepfakes, and ‘disruptive communication’ (“fake news,” disinformation, and misinformation) (Livingston & Bennett, 2020). This is, in part, because of the business model of platforms which is premised on attention capture, data, and the cultures of “virality” and content recommendation. Nick Srnicek (2017) calls this platform capitalism.

When these events happen, these ‘public shocks’ (Ananny & Gillespie, 2017), such as the unfettered racial attacks on England footballers in 2020 and the spread of violent fake news on social media about the conflict in Syria, users reevaluate the responsibility of the platforms and demand accountability. And how do platforms react?

The Scare of Too-little-too-much Moderation

In recent times, the consequences of no moderation by social platforms have become unthinkable. On the one hand, there is renewed activism from all corners for the regulation of social media sites and their practice of content distribution. On the other hand, platforms are on edge by user attrition and are reviewing their moderation policies to remain competitive. Quoting Burgess et al. (2017), “platforms face a double-edged sword: too little curation, and users may leave to avoid the toxic environment that has taken hold; too much moderation, and users may still go, either because what was promised to be an open platform feels too intrusive or too antiseptic.”

The volume of user-generated content published on modern social media platforms is staggering and makes it impossible to efficiently sort through all, even with the use of machine detection systems. Efficient moderation will mean that not just the nature of the content is checked, but also its intent, unintended consequences, and meaning(s). Then, it must be checked against the policy of the platform itself (Roberts, 2019). The sheer complexity of this pushes platforms to shroud their moderation process in secrecy and devise easy, often questionable, means to do the ugly business of moderation.

Sometimes, they run a tier system, like Facebook’s leaked prioritisation system, preferentially moderating content from certain countries and not others. Often, they adopt a combination of machine-detection systems and hired human reviewers (click workers) who are situated on the frontline to receive the barrage of unwholesome content. Often based in countries where labour is cheap, these click workers are handed a blanket policy document on what can and cannot stay on the platform to decide on content in seconds. Many large-scale platforms reserve their internal team for policymaking and adjudication in hard cases.

Following the United States 2016 Presidential Election that took Donald Trump to the Presidency, Facebook was accused of data misuse in events that influenced the outcome of the election and was slammed with a $5 billion fine for privacy violations. Later that year, its founder Mark Zuckerberg announced the launch of an independent fact-checking programme to stem the tide of fake news and disinformation. Eight years later, in January 2025, he announced a sudden about-turn, accusing the hired independent fact-checkers of being politically biased; hence fired. But one name appears in both episodes of Facebook’s (now Meta) moderation policy change– Donald Trump.

Meta’s Case Study: “We didn’t want to be the arbiter of truth”

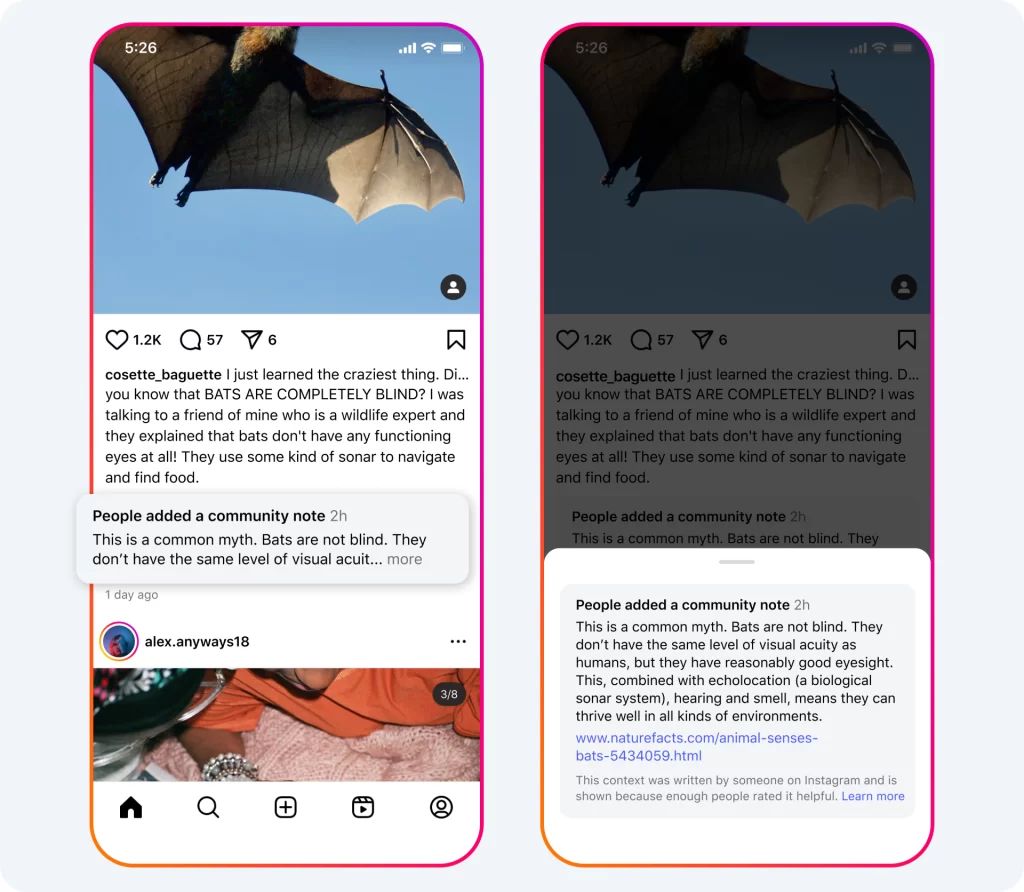

The year is 2025. Meta fired its US fact-checking agency with a promise to give some select users the reviewers’ power through a feature known as Community Notes. In what the company described as an attempt at “more speech and fewer mistakes”, Meta, on March 18, rolled out versions of its Community Notes for Facebook, Instagram, and Threads users in the United States in the tech giant’s most recent addition to efforts to “give people a voice.”

This follows a similar move by X in 2022, when the controversial social platform took its new name and introduced the system of collaborative fact-checking to ensure free flow of more-rounded opinions and views.

While a new contrivance, the idea of crowdsourcing for verification finds its root in concepts such as collective intelligence and combinatorial innovation (McAfee & Brynjolfsson, 2017) that have been touted by internet optimists as gains of Web 2.0.

What is Community Notes?

Community Notes is built on a crowdsourcing technology where select contributors create notes that attempt to add context to content shared on a platform. A key point to hold is that not every created note will be shown to users. For a note to become publicly visible, contributors who have sometimes disagreed in their past ratings must agree on such a note. This is designed to encourage diverse perspectives and prevent one-sidedness. While, on the surface, this seems like a strong proof, there are many reasons why it might become another ineffectual design.

A Win for Free Expression or Tech Oligarchy?

“We’re going to work with President Trump to push back on governments around the world that are going after American companies and pushing to censor more.” – Mark Zuckerberg, January 7, 2025.

Arguably, since its founding in 2004, Facebook (now Meta) has faced the most techlash among popular platforms, particularly regarding issues like privacy and mis/disinformation. Worsened by accusations of illegal involvement in the US 2016 Election, Meta developed a more complex system of content moderation in partnership with traditional fact-checkers, including news companies, the stem the tide of fake news, to the consternation of Donald Trump who has always been vocal against censorship and “legacy media.” However, the tension between Meta and Donald Trump heightened when in 2021, Meta banned Trump’s accounts across its platforms because the risk of letting Trump stay was “simply too great,” according to Mark Zuckerberg. This was after Donald Trump called his supporters who stormed Capitol Hill “patriots” and vowed not to attend the President-elect, Joe Biden’s inauguration.

Meta wasn’t the only social media to suspend Trump following the Capitol Hill event. Twitter, then owned by Jack Dorsey, also deplatformed the populist politician on the grounds that he was glorifying violence. However, a twist of fate began when Trump’s critic-turned-ally, Elon Musk bought and subsequently renamed Twitter (to X), reinstated Trump’s account, and introduced Community Notes.

There are concerns that Meta’s adoption of X’s style, especially now, closely following Donald Trump’s re-election, and the public criticism of legacy media by Mark Zuckerberg, in a Trump-like manner, is more political than for public interest. The recent bromance between X’s owner, Elon Musk, and President Donald Trump has spurred conversations on the implications of tech oligarchy with more and more users complaining about the unfair proliferation of pro-Trump content, including conspiracy theories and disinformation on the platform. With Zuckerberg now making the same face, there is much to be feared.

Community Notes: Does it really work?

Crowdsourcing offers many gains for internet culture that can be too difficult to overlook. Wikipedia is a successful story. Through the collective intelligence of internet users, services are democratised, made cheap, and made inclusive. We can say the same for community notes.

For instance, the approach is found to be faster in response than expert fact-checking. According to one opinion article by Bloomberg, it takes less than 14 hours on average to create a note and reach a consensus among contributors for a misleading post on X, while Meta’s old fact-checking system could take up to a week. Also, community notes are largely transparent and of high quality. Contributors often include their verification sources and clickable links for users who are interested in further reading.

People also tend to believe community notes more than the opaque fact-checking systems. It is frustrating for users to see a “misleading post” label on their posts or to have their posts removed by unknown “expert fact-checkers”. Community notes look more democratic and halve the rate of retweets on inaccurate posts (Renault et al., 2024).

On the other side of the coin, although faster than alternatives, community notes still do little to curb the spread of misinformation. Usually, before a misleading post gets a note, the damage is done. Internet communication is characterised by its immediacy, and ten hours of verification is enough window for great harm.

More so, the need for consensus for community notes drastically affects the number of community notes that get shown. The bridging algorithm of community notes requires opposing contributors to agree, but that is more difficult than it sounds. Many notes are written, but only a handful get the required diverse ratings and are shown.

Falsehood flies, and the truth comes limping after it – Jonathan Swift 1710

While it is easy to put all the blame for “fake news” and disinformation on platforms, doing so will be myopic. In many cases, people often rely on public authorities, including politicians, leaders, and journalists as arbiters of fact to construct meaning (Livingston & Bennett, 2020). When these institutions themselves are complicit, disruptive communication reigns.

Platforms should, however, refrain from shifting the responsibility of moderation to users. It is ironic to see that instead of focusing on techniques to curb the spread of inaccurate content, which they subtly encourage by incentivising viral content, they ask users to gatekeep, while they wear a clownlike freedom-of-expression mask.

References

Ananny, M. & Gillespie, T. (2017) ‘Public platforms: Beyond the cycle of shocks and exceptions’, Interventions: Communication Research and Practice, presented at the 67th Annual Conference of the International Communications Association, San Diego, CA.

Burgess, J., Marwick, A., & Poell, T. (2017). The SAGE Handbook of Social Media. SAGE.

Flew, T. (2022). Regulating platforms. Polity.

Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the internet: Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions that Shape Social Media. Yale University Press.

Livingston, S. & Bennett, W. L. (2020) A Brief History of the Disinformation Age: Information Wars and the Decline of Institutional Authority. In S. Livingston & W. L Bennett (eds.) The Disinformation Age: Politics, Technology, and Disruptive Communication in the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 3-40

McAfee, A., & Brynjolfsson, E. (2017). Machine, platform, crowd: Harnessing our digital future. W. W. Norton & Company.

Renault, T., Amariles, D. R., & Troussel, A. (2024). Collaboratively adding context to social media posts reduces the sharing of false news. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.02803.

Roberts, S. T. (2019). Behind the screen: Content Moderation in the Shadows of Social Media. Yale University Press.

Srnicek, N. (2017). Platform Capitalism. John Wiley & Sons.

Be the first to comment