Introduction

Can you imagine logging into Facebook and discovering strangers openly discussing whether individuals like you should exist? For many online users with disabilities, this is not a hypothesis, but rather an actual situation they encounter on social media platforms.

Although the immediacy and globalization of digital platforms like Facebook have greatly changed the way individuals communicate, they have also led to a surge in hate speech. Due to regulatory challenges, hate speech against individuals with disabilities on social media platforms is often tolerated.

Individuals with disabilities are one of the groups deeply affected by hate speech, but their experiences have not been widely discussed like those of ethnic minorities and religious groups. To fill this gap, this blog will help understand hate speech towards disabled groups and explore the challenges of regulating disability hate speech on social media platforms, with a primary focus on Facebook. The ‘60 Minutes Australia Facebook’ case will be discussed in the blog, while another example of hate speech towards short-statured Australians on Facebook will also be mentioned.

The following is the main description of the case study ‘60 Minutes Australia Facebook’ to facilitate understanding of the upcoming sections of the blog. The study is based on discourse analysis of public comments of the discussions established on the 60 Minutes Australia Facebook site in 2017, with the topic of ‘Does Australia really want to see the end of Down syndrome?’. The discussion threads on Facebook generated nearly 1,600 comments and were viewed by over 300,000 users. The case is useful for studying the problems of disability hate speech on social media as it showcases the diverse types of online hate speech towards individuals with disabilities and reveals the difficulties in managing online disability hate speech.

Understanding Hate Speech Towards Disabled Individuals on Social Media

Hate speech is defined as speech that expresses, encourages, or incites hatred towards a group of people characterized by specific characteristics or a series of characteristics such as race, ethnicity, gender, religion, nationality, and sexual orientation. It stigmatizes groups by associating them with negative or socially unpopular characteristics, which can lead to serious psychological harm, social exclusion, and even withdrawal from the public for victims (Flew, 2021).

Vedeler et al. (2019) cited a series of studies showing that compared to non-disabled groups, individuals with disabilities are more likely to become victims of violence and hate speech. The word ‘Ableism’ is helpful for understanding the hate speech towards disabled users, which means systemic and social discrimination or denigration against groups with disabilities, typically based on the belief that non-disabled individuals are superior. Under the system of ableism, individuals with physical, intellectual, or psychosocial differences who are unable to integrate into a normative society are considered ‘others’, while the dominant position of able-bodied individuals in the social power structure allows them to exclude these ‘others’ (Johnson & West, 2021).

Therefore, online hate speech against users with disabilities reflects a broader sense of societal ableism and expands the notion that disabled groups are not equal to other members of society under the ableism system, leading to them being more marginalized.

According to the relevant research, there are several common types of online hate speech towards users with disabilities, including the theory of socio-economic burden, the narrative of ‘best interest’, and the humiliation of parents of individuals with disabilities (Johnson & West, 2021).

On the internet, users who advocate for ableism view disabled individuals’ use of social funds and services as an unnecessary drain on public resources. For instance, in the mentioned case, some users used terms such as ‘parasites’ and ‘burden of taxpayers’ to call individuals with Down syndrome on Facebook. Also, a group of users in the discussion argued that some disabled individuals who can be tested for diseases through prenatal examination should not be born, as this can expel defective genes and is in the ‘best interest’ of society. Therefore, they believed that children with Down syndrome should be eliminated through abortion once they are detected for diseases through prenatal checkups. Furthermore, parents of children with disabilities, especially those who knowingly give birth to disabled children, are accused of selfishness and irresponsibility. In the Facebook discussions, the parents of children with Down syndrome were criticized for comments such as ‘children suffer because of their parents’ decisions’.

In a word, these kinds of narratives would reinforce discrimination against individuals with disability and cause psychological trauma to disabled users. Nevertheless, due to the challenges of regulating disability hate speech on the platforms, it is difficult to effectively control this hate speech, which leads to deeper social prejudice.

What Are the Main Challenges of Regulating Disability Hate Speech on Social Media?

- The Difficulties in Balancing Free Speech and the Management of Hate Speech

Under the guise of freedom of expression, many hate and discriminatory online speech are defended as ‘opinions’. Hence, this poses a fundamental challenge of balancing the protection of disabled groups with maintaining a free and open public discourse.

Article 19 of the UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights stipulates that everyone has the right to freedom of speech, including the freedom to receive and impart information and ideas through the media. However, Article 20 of this document also states that any behavior that constitutes incitement to discrimination and hostility should be prohibited by law (Flew, 2021). Therefore, this document reflects the contradictions between promoting free speech and effectively enforcing legal sanctions against online hate speech.

In addition, John Perry Barlow once claimed in ‘Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace’ to create a world through the Internet where anyone can express his or her ideas, without worrying about being forced to remain silent (Flew, 2021). But considering the current online environment, this absolutism of free speech seems unacceptable as it would enable the proliferation of online hate speech.

Furthermore, Johnson and West (2021) pointed out that some hate speech may not seem as cruel as direct insults, but still carries strong discriminatory connotations, which can cause offense and psychological harm to victims through targeted communication. This type of hate speech is particularly difficult to manage because it does not involve explicit violence or threats, nor does it touch the moral bottom line.

The case of ‘60 Minutes Australia Facebook’ is useful for understanding the challenges of balancing freedom of speech and the management of hate speech towards individuals with disabilities, especially the difficulty of regulating indirect disability hate speech.

In these Facebook discussions, the comments about ‘best interest’ and the accusations against the parents of children with Down syndrome intuitively illustrate this dilemma. Many of the harmful comments under these posts, such as those expressing ‘Down syndrome patients should not be born, as it is in the best interest of society’, are usually not recognized as hate speech, but rather as ‘personal opinions’ or even ‘rational opinions’. These statements conceal their discriminatory nature in a rational tone, making them harder to regulate under existing laws and platform policies. Also, some comments advocated that ‘preventing the birth of Down syndrome children through prenatal testing and abortion can help these children avoid facing pain and difficulties’, and accused the parents of Down syndrome children for this reason. These viewpoints may seem sympathetic and do not incite violence, but they would reinforce eugenics ideology and promote the notion that disabilities are inferior to others.

To sum up, the comments mentioned above are difficult to be controlled because they are not restricted under the fundamental values of freedom of speech in Australia, and do not cross the legal threshold for hate speech. However, these comments still reflect prejudice against individuals with disabilities and their families, and could lead to their exclusion from the digital space.

- The Loopholes in Platform Governance of Hate Speech

The loopholes in platform governance are also one of the difficulties faced in regulating online hate speech towards individuals with disabilities. Although the internal structure, policies, and processes for handling hate speech on many platforms are rapidly developing, there are still many aspects that need to be improved.

For instance, Facebook has strengthened its collaboration with academia and civil society organizations to enhance understanding and monitoring of hate speech. However, it still has shortcomings in defining hate speech too narrowly and causing user ‘reporting fatigue’. Sinpeng et al. (2021) suggested that Facebook’s definition of hate speech would allow some hate speech with subtle malicious to escape censorship. In addition, many users have provided feedback that when they report comments they perceive as hate speech to Facebook, the reported comments are not deleted or there is a lack of appropriate follow-up. As a result, users would experience ‘reporting fatigue’ due to their disappointment with Facebook’s response, reducing their willingness to use the reporting tool (Sinpeng et al., 2021).

The case of ‘60 Minutes Australia Facebook’ reflects how speech with subtle discrimination can escape censorship, as well as how disabled users generate ‘reporting fatigue’ on Facebook.

In the discussions, much hate speech related to disabilities is found to contain subtle discriminatory connotations and have a condescending perspective towards individuals with disabilities. For example, a user with an economic rationalist stance said, ‘We cannot distribute social resources to everyone’ (Johnson & West, 2021). The hidden meaning of this comment is that disabled groups are less deserving of resources than able-bodied individuals, thus constituting discrimination against individuals with disabilities. Nevertheless, the statement did not meet Facebook’s internal threshold for hate speech, which resulted in it not being deleted. Moreover, some users have also reported inhumane hate speech against individuals with Down syndrome, but only received an automatic response from Facebook stating that the content did not violate community standards (Johnson & West, 2023). Hence, due to Facebook’s lack of action, disabled users would develop ‘reporting fatigue’ and begin to respond to hate speech through grassroots ‘resistance narratives’.

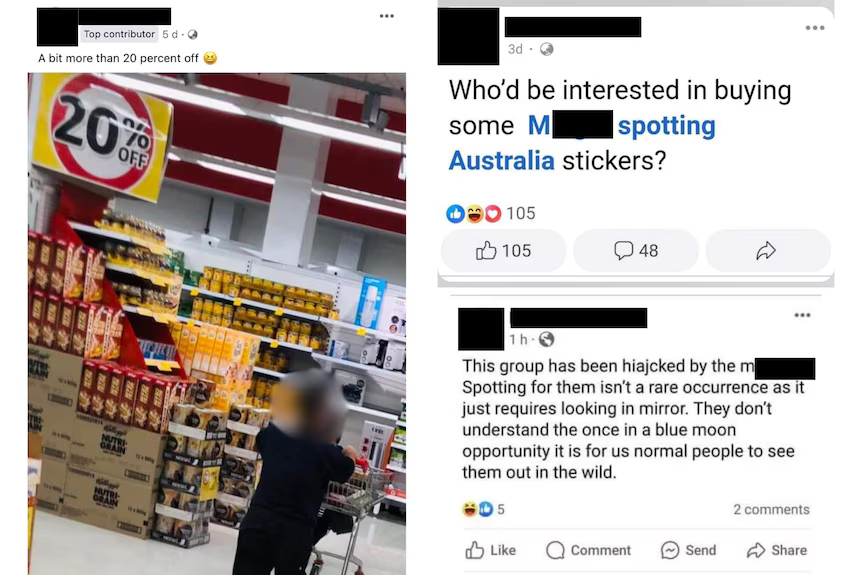

In addition, another current example of online abuse faced by short-statured Australians also illustrates Facebook’s problem with defining hate speech and ‘reporting fatigue’.

In 2024, short-statured Australians reported that they have found their photos increasingly taken and posted on ‘m****t spotting’ social media groups without consent, and these groups contain comments with violent and pornographic elements. On Facebook, a group called ‘M*****t spotting Australia’ with the tagline ‘See something small, give us a call’ was found to have collected unauthorized photos of short-statured Australians with derogatory comments attached. Although the group was reported to Facebook, it was not deleted because Facebook believed that the group ‘did not violate the community standards’ (Young & Taouk, 2024). This indicates that the overly vague definition of hate speech in Facebook’s community standards made abusive behavior towards short-statured Australians to escape punishment and be tolerated. Therefore, short-statured Australian users would feel frustrated and powerless, which is a characteristic of ‘reporting fatigue’. For instance, Mr. Millard and Ms. Lilly both expressed disappointment with Facebook’s management of hate speech after the report was unsuccessful and hoped that Facebook could take more action (Young & Taouk, 2024).

What Improvements Can be Made in Regulating Hate Speech Towards Disabled Individuals in the Future?

Regarding the above discussion on the loopholes in Facebook’s management of hate speech, social media platforms can primarily improve their governance of hate speech against disabled individuals by refining the definition of hate speech and combating the ‘reporting fatigue’.

First, platforms can expand the scope of ‘hate speech’, which should not only include direct threatening speech and violent speech, but also indirect that may harm one’s dignity. For example, a comment on Facebook suggesting that individuals with disabilities do not deserve equal rights as others should be considered hate speech and removed because although it does not trigger existing hate speech rules, it reflects bias against disabled groups. For redefining hate speech, platforms can collaborate with groups often targeted by hate speech and better define hate speech based on their experiences of being harmed by online hate speech.

Also, platforms should address the issue of inaction towards hate speech, as it erodes users’ trust in platforms. The platforms can improve the efficiency of handling hate speech, and provide users who fail to report specific reasons why their reports are rejected rather than simply automatic replies. Furthermore, for posts that do not meet the deletion threshold but contain malicious content, platforms can reduce their spread by limiting their frequency and other methods.

Conclusion

To sum up, disability hate speech on social media is an underappreciated and harmful issue, reflecting the discrimination of disability groups by ableism. Through the discussion of the ‘60 Minutes Australia Facebook’ case and recent example of online hate speech towards disabled groups, it can be seen that the difficulty in balancing freedom of speech and managing hate speech, as well as the loopholes in platform governance, have led to the continued existence of online hate speech against disabled individuals. Therefore, platforms such as Facebook should make meaningful reforms in their management of hate speech to curb it and create a safer online environment for individuals with disabilities.

Bibliography

Flew, T. (2021). Issues of Concern. Regulating platforms (pp. 91-96). Polity.

Johnson, B., & West, R. (2021). Ableist contours of down syndrome in Australia: Facebook attitudes towards existence and parenting of people with down syndrome. Journal of Sociology (Melbourne, Vic.), 57(2), 286-304. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783319893474

Johnson, B., & West, R. (2023). Ableism versus free speech in Australia: challenging online hate speech toward people with Down syndrome. Disability & Society, 38(9), 1711-1733. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2022.2041402

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F. R., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021). Facebook: Regulating Hate Speech in the Asia Pacific. Department of Media and Communications, The University of Sydney. https://doi.org/10.25910/j09v-sq57

Vedeler, J. S., Olsen, T., & Eriksen, J. (2019). Hate speech harms: a social justice discussion of disabled Norwegians’ experiences. Disability & Society, 34(3), 368-383. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2018.1515723

Young, E., & Taouk, M. (2024, May 29). “It’s become a bit of a sport”: The “disgusting” online abuse faced by Sam and her community. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-05-30/short-statured-community-call-out-online-abuse-facebook-groups/103896180

Be the first to comment