Introduction

In today’s society, social media has become an important platform for people to obtain information and communicate, and it is especially ubiquitous among young people. However, with the popularity of social media has come a rise in hate speech.

The 2019 Christchurch mosque shooting in New Zealand was harrowing, with the killer studying Norway’s 2011 terror attack through social media, mimicking its online communication strategy, and ultimately killing 51 people. The live video of the shooting was shared over 4 million times, a heinous act that inspired extremists around the globe to follow suit, as in the case of the Halle shooting in Germany(BBC News, 2019).

New Zealand mosque gunman pleads guilty to murder, terrorism

Hate speech on social media is not just a whim in the internet, they can also be linked to real-life hate crimes.

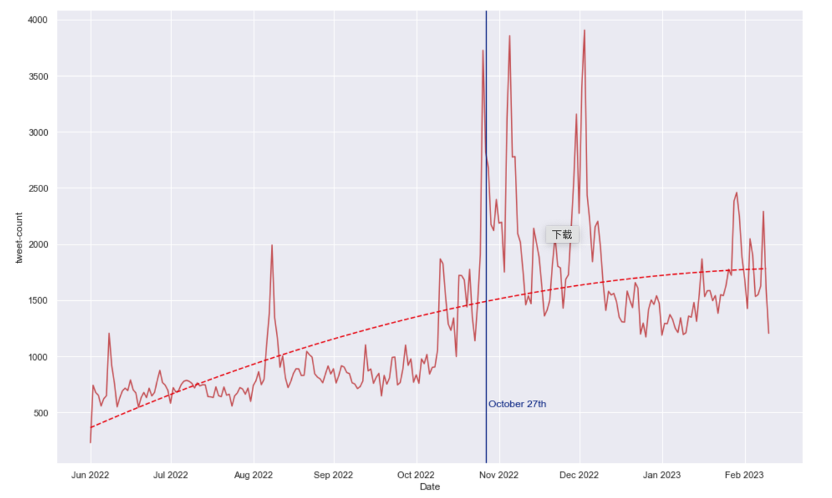

Case study: Musk’s acquisition of Twitter

A new study by CASM Technology and ISD has found that the number of anti-Semitic posts on Twitter has continued to increase significantly since 27 October 2022, when Elon Musk acquired the company. 325,739 English-language antisemitic tweets were detected over a nine-month period from June 2022 to February 2023, representing a 106 per cent increase in the average number of antisemitic tweets per week (from 6,204 to 12,762) compared to before and after Musk’s acquisition (Behavioural and Experimental Analysis of Media, 2023).

Figure 1: volume of potentially antisemitic Tweets over time, June 2022 – February 2023

Particularly on delicate subjects like politics, race, and gender, the study shows how public opinion and social stability are shaped by social media channels.

Reacting to the outcomes, Musk asserted that “algorithmic transparency” will fix things.

However, it has been proven that the relaxation of censorship has made it easier for hateful content to spread (X Safety, 2023).

So why did I choose this case for discussion?

Hate speech

Musk’s acquisition of Twitter is dripping with the inherent conflict between the idea of neutrality at the algorithmic level and the structural biases of society. Musk stated at the time of his acquisition of Twitter, ‘Freedom of speech is the cornerstone of a functioning democracy.’

He argued that the original platform was overly censoring viewpoints and greatly limiting the space for public discussion. At the same time, he is committed to and in favour of reinstating Trump’s account, actively advocating for ‘algorithmic transparency’ and ‘absolute freedom of speech’.

Figure 2: Musk: Free speech is the bedrock of democracy

1. The Essence of the Dispute: Algorithmic Impartiality vs Societal Structural Prejudice

Is Musk’s discourse on ‘algorithmic transparency’ indeed transparent? The notion of algorithmic neutrality, shown by the public availability of recommendation code, may give an illusion of technological impartiality; yet, the algorithms remain inextricably linked to the social prejudices inherent in the training data.(Crawford, 2021).

The design and training of algorithms is essentially a process of encoding social power – the cognitive limitations of the developer, the historical biases of the data, and the value trade-offs in technical decision-making combine to build the rules of the machine learning system. Essentially, machines learn from human behaviour and human ways of thinking, and when humans embed their own social logic into the code, algorithms cease to be neutral technological tools and become digital reproduction machines of structural discrimination (Crawford, 2021).

Algorithms are like mirrors

2. Content censorship vs. freedom of expression

The Twitter platform’s algorithms recommend content based on user behaviour, which can lead to a snowballing of hate speech. If someone likes anti-Aboriginal content, the system pushes more similar content.

Sydney Swans fans supporting Adam Goodes after he was targeted.

For example, when Australian Aboriginal footballer Adam Goodes sparked controversy for doing a traditional war dance during a match, there was a flood of racist attacks on social media, with users using ‘sensitive content’ filters to hide offensive images, and Twitter was not able to effectively recognise the disguised hate speech. (Matamoros-Fernández, 2017; Crawford, 2021).

Moreover, Musk’s layoff of 75 percent of his content review team was not only motivated by ‘freedom’ ideals but also a business decision to compress costs. This is an impressive situation where Elon Musk is only concerned with the numbers game rather than creating and nurturing a beneficial culture (Chandani et al., 2024).

The ‘absolute freedom’ model masks the essence of the platform’s shift of governance responsibility to the user. This model relies on automated systems, but AI auditing has limitations such as difficulty in recognising context, and irony (Chandani et al., 2024). Users think they are freely choosing content, but are actually trapped in an algorithmically woven ‘ information cocoon’. Platforms recommending content based on user behaviour can lead to hate speech spreading like a snowball (Morales, Salazar, & Puche, 2025).

As hate speech increases, so does the sense of divisiveness and unease in society, especially in the context of the current global political turmoil, which makes the role of social media particularly important. The increase in hate speech is closely related to user interactions (e.g., likes and retweets) that not only amplify the impact of hate speech, but also make it more widely available on the platform.

For example, if someone likes anti-Aboriginal content, the system will push more similar content. Far-right content, for example, may be recommended to more people, and hate speech spreads like a virus. As a result, Platform X has gone from public square to hate amplifier. The design of the platform makes it easier for racist speech to spread and even creates cyber-violence, forcing victims (such as Goodes) to withdraw from the public sphere(Matamoros-Fernández, 2017).

Hate speech is more likely to proliferate under the push mechanism of the platform’s algorithms, which also allows the platform to reap more attention traffic and make more money.

Similar problems have arisen on Twitter (now Platform X) in the context of the escalating Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Media Matters, a US media watchdog organisation, found that advertisements from companies such as IBM, Disney and Apple were appearing next to content promoting Hitler and Nazis on the X platform (Montgomery, 2023).

At least two major corporations decided to pull their funding (advertising) from Platform X when Musk posted controversial tweets involving Jews. Prior to this, since Musk’s acquisition of Twitter Inc. in October 2022 and the reduction of content moderation, a number of advertisers have fled the platform due to a sharp rise in hate speech (Montgomery, 2023).

This phenomenon suggests that the platform’s failure to effectively control the content environment surrounding advertisements has led to a negative correlation between advertising and the spread of hate speech.

Big companies like IBM, Disney and Apple have stopped advertising on Platform X

In fact, not only Twitter, for example, the algorithmic design, community governance and cultural atmosphere of platforms like Reddit also unintentionally contribute to these ‘toxic technology cultures’. Reddit’s management has long upheld the principle of a ‘neutral platform’ and is reluctant to intervene in content disputes, believing that the community should be allowed to determine its own rules (Panek, 2021).

This attitude has effectively condoned hate speech and harassment, and The Fappening was delayed from being banned due to the advertising revenue generated by its traffic (Panek, 2021).

Libertarians often equate ‘freedom of speech’ with ‘freedom from government intervention’, but the essence of the rules of private platforms is the monopoly of private power over public discourse (Gillespie, 2020) .

What are the trade-offs for platforms when the right to security for minorities conflicts with the right to expression for the majority? Where are the boundaries of ‘freedom’ for ordinary people?

3. Current status of regulatory responsibilities and legal challenges

The Members’ Research Service (2024) observes that the Digital Services Act (DSA) mandates platforms to proactively censor illegal information and implement transparency procedures; nonetheless, critics contend that it may excessively infringe upon the operational autonomy of private enterprises. The EU has requested that Platform X provide data regarding its algorithm design, content review policies, and hate speech management to evaluate its adherence to the DSA’s transparency mandates for mega-platforms (those with over 45 million monthly users).

The enforcement of the DSA at the national level is significantly constrained by implementation delays. Enforcement of the DSA at the national level remains very limited due to implementation delays. At the European level, the Commission has initiated formal proceedings against five very large platforms and has initially ruled that Platform X is not compliant with the Act. Other investigations are still ongoing.

Digital Services Act

The eSafety Commissioner (Online Safety Council) in Australia oversees social media sites and makes them delete illegal content like hate speech and child exploitation videos right away. Australia’s Online Safety Act says that Platform X must take down any material that is found to be illegal. If it doesn’t, the company could be fined up to $550,000.

The $550,000 cap on fines is a ‘tickle’ for Platform X (with a market capitalization of $19bn) and is far less than the advertising revenue it generates from hateful content, making it difficult for it to generate any revenue.The revenue generated from hateful content much exceeds this amount and is unlikely to effect a major change in X’s hostile content (Chandani et al., 2024).

In the absence of legal safeguards, there exists a considerable risk that platforms and algorithms would retain unchecked authority.

4. How can hate speech be managed?

Behind the seemingly ‘neutral’ technology of social media lies a systematic bias against specific groups. Platforms need more transparent vetting mechanisms and more culturally sensitive algorithm design, rather than simply relying on the excuse of ‘freedom of speech’ to allow hate speech to spread.

At the platform level: platforms need to be held jointly and severally liable for algorithmically recommended content (e.g., active pushing of hate speech), not just passive hosting of user-generated content; Twitter should work with protected groups to clarify forms of hate speech and incorporate them into vetting policies, disclose information about trusted partners; organise annual hate speech roundtables, and disclose content policing procedures (Sinpeng et al., 2021). 2021).

At the legal level: the rise of global compliance coalitions: setting up a network of fines: the EU and Australia have signed a joint enforcement agreement to ‘relay fines across continents’ to non-compliant platforms – one violation, all areas are held accountable at the user level. Dynamic blacklists: establish a transnational hate speech database and force platforms to update their filtering terminology (e.g. the EU’s ‘anti-terrorism content blacklist’).

At the individual level: give users the freedom to turn off algorithmic recommendations, and websites should not require users to disclose their personal information before they can use the services provided by the website. Users need to be trained in ‘anti-algorithmic’ behaviours, such as actively liking longer posts, to reduce the system’s reliance on short, controversial tweets. Blocking keywords: Add filter tags such as ‘political’ and ‘racial’ to your settings.

Elon Musk’s legal representative has written to CCDH saying the organisation has made ‘inflammatory, outrageous, and false or misleading assertions’. Photograph: David Talukdar/Shutterstock

Conclusion

Musk’s Twitter experiment is like a digital prism that reflects the hypocrisy of algorithmic neutrality – it claims to illuminate the ‘utopia of freedom of expression’, but magnifies society’s deepest fissures into an abyss. When platforms use ‘technological neutrality’ as a shield, they allow hate speech to spread virally, fuelled by algorithms.

We have to admit: the freedom of algorithms is never innocent.

The way forward requires not only regulatory adjustments, but also a reimagining of the social contract of technology. Just as factories adopt safety standards in the wake of industrial tragedies, platforms must embed ethical antibodies in their code:

Transparency: Open source not only algorithms but also training data and audit logs.

Reparations: Give a percentage of profits to the communities most harmed by hate speech.

Participatory design: Include civil rights leaders on technical committees with veto power over harmful features.

The answer to hate speech is not to eliminate algorithms, but to restructure their internal DNA. The law needs to evolve from a tickler to a scalpel, forcing platforms to be jointly and severally liable for algorithmically recommended content;

Technology adds ‘moral antibodies’ to avoid bias through technology, stripping data of toxic culture; and every user should awaken from a ‘traffic slave’ to an ‘algorithmic citizen’. –Vote for a more conscious digital society with every click of your fingertips.

Reference

BBC News. (2019, March 15). Christchurch shootings: 49 dead in New Zealand mosque attacks. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-47578798

Behavioral and Experimental Analysis of Media. (2023). Antisemitism on Twitter before and after Elon Musk’s acquisition. https://beamdisinfo.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Antisemitism-on-Twitter-Before-and-After-Elon-Musks-Acquisition.pdf

Chandani, A., Pande, S., Dubey, R., & Bhattacharya, V. (2024). Elon Musk and twitter: A saga of tweets. In Sage Business Cases. SAGE Publications, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071927014

Crawford, K. (2021). The atlas of AI: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press.

Gillespie, T. (2020). Content moderation, AI, and the question of scale. Big Data & Society, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720943234

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: The mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1293130

Members’ Research Service. (2024, November 21). Enforcing the Digital Services Act: State of play. Epthinktank. https://epthinktank.eu/2024/11/21/enforcing-the-digital-services-act-state-of-play/

Montgomery, B. (2023, November 17). Apple, Disney and IBM to pause ads on X after antisemitic Elon Musk tweet. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/nov/17/elon-musk-antisemitic-tweet-apple-pausing-ads

Morales, G., Salazar, A., & Puche, D. (2025). From deliberation to acclamation: How did Twitter’s algorithms foster polarized communities and undermine democracy in the 2020 US presidential election. Frontiers in Political Science, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2024.1493883

Panek, E. T. (2021). Understanding Reddit (1st ed., pp. 1–57). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003150800

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F. R., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021). Facebook: Regulating hate speech in the Asia Pacific. The University of Sydney. https://hdl.handle.net/2123/25116.3

X Safety. (2023, April 17). Freedom of speech, not reach: An update on our enforcement philosophy. X Blog. https://blog.x.com/en_us/topics/product/2023/freedom-of-speech-not-reach-an-update-on-our-enforcement-philosophy

Be the first to comment