Step 1—you cannot.

How wonderful it is to just live in a world of rainbows and butterflies, people understanding each other—never having conflicts, always meeting eye-to-eye, peaceful and not having to think about offenses, and being sensitive because everyone just loves everybody. But the world we live in is otherwise. Yes, there are rainbows above, but the people have never-ending quarrels below. Life on earth is indeed a walk in the park—a Jurassic Park.

I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but what is happening in the real world also happens in the digital world.

Meanness here and there—social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, X (formerly Twitter), TikTok, and YouTube could be harsh. It is as if social media platforms are sliding away from its original purpose. Facebook should connect people, and while it is true for some, its users sometimes cause strife, tarnishing its objective to bring people from all around the world together.

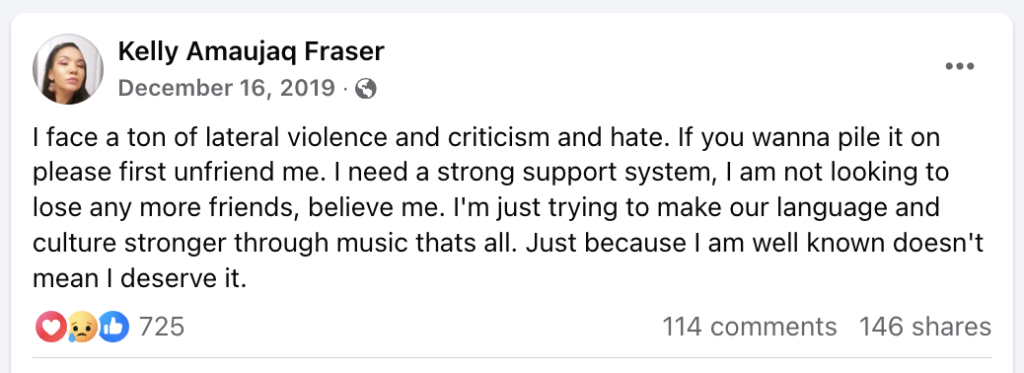

Hate speech, if left rampant and unchecked, could cause serious consequences. On Christmas Eve of 2019, Kelly Fraser was found dead at her home in Winnipeg, Manitoba. Kelly was a well-known singer in her community, but this did not exempt her from experiencing bullying and hate speech online.

Days before she committed suicide, she posted on Facebook saying, “I’m just trying to make our language and culture stronger through music that’s all. Just because I am well-known doesn’t mean I deserve it.” her post insinuated a possible conflict with her music within the community she belongs to. The continued hatred she got in person and online made her decide to take away her life.

Ryan Patrick Halligan was another victim of bullying—both in person and online. Ryan committed suicide on 7 October 2003. At the time of his death, Ryan was a middle school student in Essex Junction, Vermont. It was revealed in much greater detail after Ryan’s death that he was ridiculed and humiliated by peers at school and online (Halligan, 2005). Kelly and Ryan are only two of the many victims of cyberbullying and online hate speech, and the numbers are increasing as days go by.

Meta is not Meta-ing enough. Through the years, social media platform giants have been exerting efforts to moderate online hate speech. In December 2016, Meta announced that they would have a Fact-Checking program on Facebook in hopes of moderating fake news, misinformation, disinformation, and online hate speech. Just recently, Mark Zuckerberg, Meta’s chief, announced on 8 January 2025 that Facebook would remove its fact-checking program as it “led to too much censorship.” In one of Mark’s videos, he added it was time for Meta “to get back to our roots around the free expression,” especially following the recent presidential election in the US. Zuckerberg characterized it as a “cultural tipping point, towards once again prioritizing speech” (Vasquez, 2025).

To keep up with the public’s clamor to have a decent and fair moderation of hate speech online, Meta will now have Community Notes—one similar to what X (formerly Twitter) is currently using. Instead of the previous professional fact-checkers, Meta leaves the matter to the 3 billion active Facebook users all around the globe by adding notes containing contexts and their opinions on specific content. But will this do the trick? Is Meta Meta-ing enough?

Studies on the effectiveness and efficiency of community notes have a myriad of results. Pros and cons, upsides and downsides. Perhaps the obvious loophole about having Community Notes is the reliability and credibility of the Notes. This is where the Notes’ voting system comes into the picture, where Notes could receive votes from other users finding the note to be helpful or truthful. Numerous studies seem to lean towards having Community Notes than the fact-checker program. An article written by Tom Stafford of the LSE Impact Blogs states that “despite limitations, in speed and reach, and vulnerabilities to biases or abuse, Community Notes is a fundamentally legitimate approach to moderation. The user community provides and votes on Notes. The problems of polarization, speech moderation, and misinformation are more significant than any crowd-sourced approach alone can handle (Stafford, 2025). This suggests that instead of the fact-checkers who may be in their ivory towers unaware of contexts and real-life situations fact-checking content, Meta gives the job to the ones who are actually in the field feeling and seeing phenomena for better contextualization.

Step 2—you can try again, but to no avail.

Defining ‘hate speech’. Now, it is essential that we define what could be considered a “hate speech” and what is “not a hate speech”. Meta considers hate speech as “hateful conduct.” They define hateful conduct as direct attacks against people—rather than concepts or institutions—based on what we call protected characteristics (PCs): race, ethnicity, national origin, disability, religious affiliation, caste, sexual orientation, sex, gender identity, and serious disease.

However, according to a study conducted by Sinpeng and Martin et al. (2021), Facebook’s definition of hate speech does not cover all targets’ experiences of hateful content. Their study also claims that Hate speech, by contrast, is viewed as regulable in international human rights law and the domestic law of most liberal democratic states (the United States being the exception) (Sinpeng et al., 2021). This means that rules on hate speech could be controlled and is able to be regulated per country. “In order to be regulable, hate speech must harm its target to a sufficient degree to warrant regulation, consistent with other harmful conduct that governments regulate (Sinpeng et al., 2021). In summary of their study, hate speech could be defined as follows:

- Hate speech needs to take place in public as public conversations ought not to be regulable.

- Hate speech needs to be directed at a member of a systemically marginalized group in the social and political context in which the speech occurs.

- The speaker needs to have the ‘authority’ to carry out the speech.

- The speech needs to be an act of subordination that inserts structural inequality into the context in which the speech takes place.

Why is it impossible to totally eliminate online hate speech? Since the total elimination of online hate speech is not possible, the only sensible solution is to “moderate” it, and moderation job for online hate speech is never easy, even if a country has a well-defined ‘hate speech.’ It is still difficult to point out who commits what.

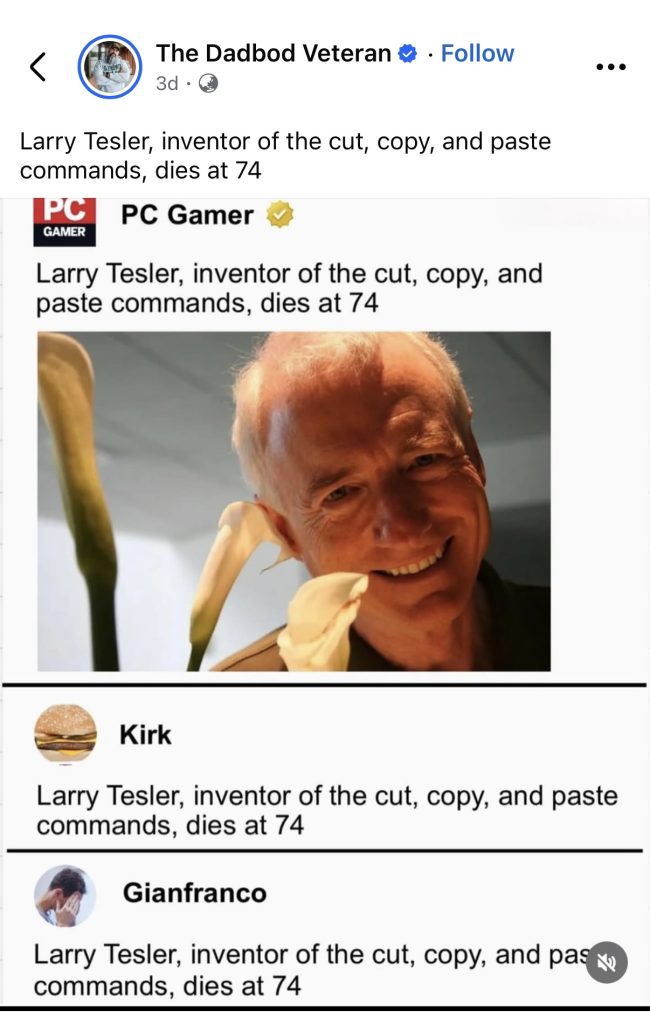

Online hate speech revolves around language use. Language is ever-changing as time goes by. Language is not static, but rather dynamic (Mahboob, 2023), it means that you cannot cage language into a specific set of rules called “grammar”. That is how flexible language is. Even if an AI is programmed to spot word cues that could be considered hate speech, social media users will find their way around to avoid being called out by an AI. In the Philippines, the Tagalog word ‘bobo’ means ‘fool’ or ‘idiot.’ If a user is caught writing it on Facebook, the platform will automatically flag the account for going against the Community Guidelines or Community Standards. But the Filipinos outsmarted the program by just typing ‘8080’. Language is a moving target, and this is one of the reasons why the total abolition of online hate speech is impossible, and moderation of hate speech is extra difficult.

Another reason is that moderation of online hate speech could be done by an AI but still needs humans to calibrate and ensure the accuracy of data. With over three (3) billion active users on Facebook alone, this requires a significant workforce. Manpower could be expensive even if it is outsourced abroad; the price the companies are willing to pay will not suffice. With this problem, hate speech moderation’s quality, speed, accuracy, and efficiency are at stake.

At this stage, I am pretty sure we have already established that we can never 100% remove online hate speech; the title of this blog is formed that way only to get your attention. However, I have come up with solutions that people may find absurd and ridiculous, but Noah appears to be crazy at first when he is building the arc—until it rains. So, these ideas may sound absurd for now, but we do not know what might happen next.

Step 3—try these crazy ideas (at your own risk)

- Social Media License – Just like driving, it would be illegal to drive without a license. What if we try to implement a Social Media Aptitude Test (SMAT) that those who want to use social media platforms must undergo and pass? The SMAT should include an Intelligence Quotient (IQ) Test to measure their substance and content and an Emotional Quotient (EQ) Test to assess potential users’ emotional stability. This ensures that we lessen the number of ‘Karens’ and ‘Darrens’ that could enter the digital world and the Adversary Quotient (AQ) Test to encourage and empower users to be resilient and tough. A user’s social media license could be revoked if they violated rules and regulations set in the Community Guidelines.

- Ban All Social Media Platforms – Now, even if there is a SMAT, people will find their way around and acquire the license even if they do not undergo the Test. There will always be loopholes in the system, and humans are good at finding them. So, another crazy idea is to ban all social media platforms and not give people an alternative but to go back to sending messages via written letters—mail. Some may find it romantic; others may find it hectic. Anyway, we cannot please everyone; there will always be criticisms, both constructive and destructive. To save our people from online hate speech, let us ban all social media platforms and give our postmen their jobs back.

- Social Media Platforms Segregation per Generation – Most hate speech is caused by misunderstanding and miscommunication. On social media platforms, we can see users clashing and not meeting eye-to-eye because of one obvious reason—the difference in their generation. So, the answer is Social Media Segregation per Generation. There should be a Facebook Page for Gen Zs, another page for Millennials, and another page for Gen X and Baby Boomers. Now, critics may say that conflicts are inevitable, and they also happen within their generation. The answer is easy; at least they only have to think about going against their own generation.

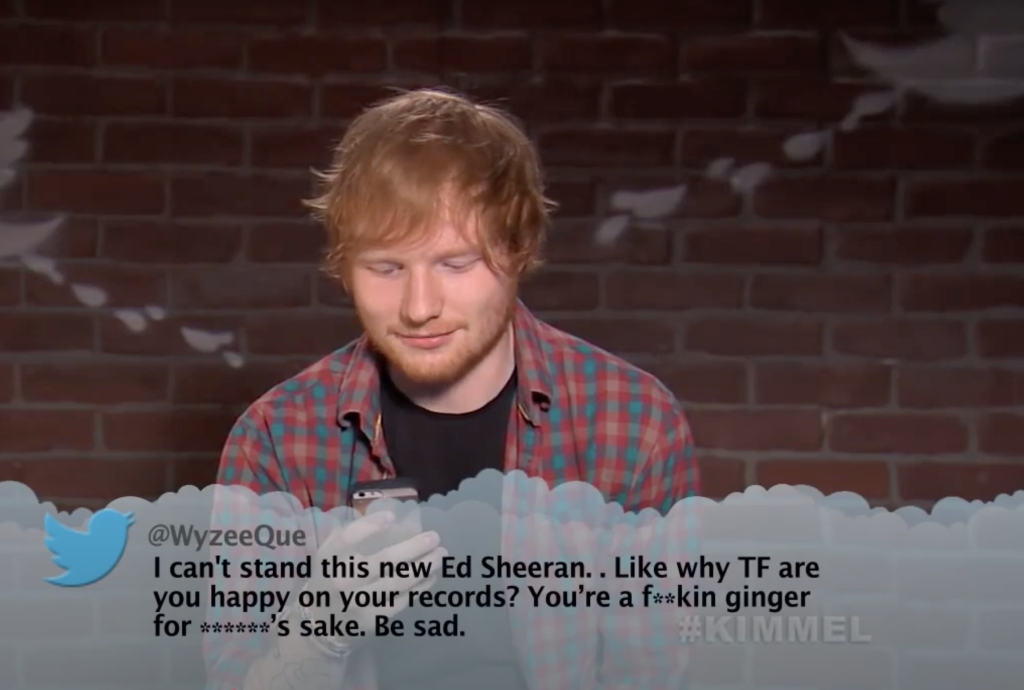

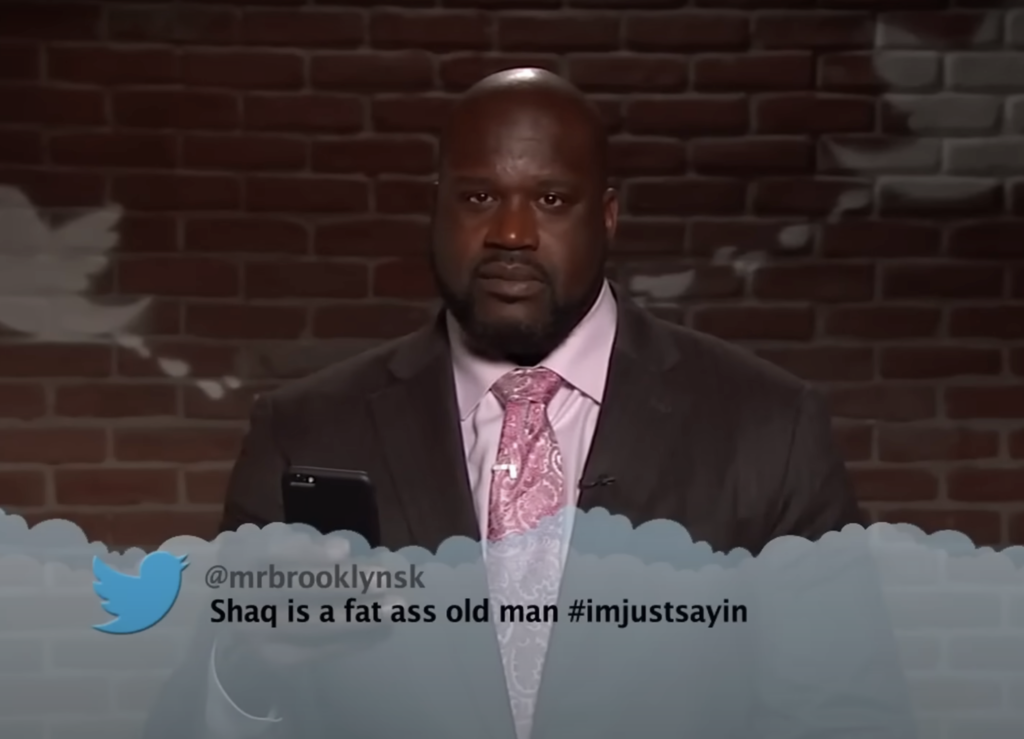

Mean Tweets segment from Jimmy Kimmel show where celebrities would read the public’s mean tweets about them

In conclusion, there are no easy steps to remove online hate speech 100%. We can moderate online hate speech, but we must also realize that hate speech moderation is a never-ending job. We can make our policies regarding online hate speech as future-proof as possible, but it is not a guarantee that they will cope with users’ use of social media from now to tomorrow. Why? Not all people live under the same roof; every person has different upbringings, and we have different beliefs, cultures, traditions, perspectives, and experiences. Online hate speech is a dangerous problem that our society should address. No one deserves to be bullied online. Bashing and lashing take a toll on its victim’s overall well-being. But if we prioritize respect and understanding and learn to tolerate each other’s differences, we could all live in harmony. The world is a better place with people speaking life populating it.

References

Kelly Fraser Facebook Page. (2019).

https://www.facebook.com/iskell

https://infotel.ca/newsitem/inuk-singers-death-highlights-lateral-violence-bullying-within-indigenous-communities-kamloops-friends-say/it69280

https://www.rcinet.ca/regard-sur-arctique/2019/12/30/mort-kelly-fraser-chanteuse-inuk-nunavut-sanikiluaq-musique-arts-prix-indspire-arctique/ (Kelly Fraser’s Photo)

Ryan Halligan. (2006). https://www.ryanpatrickhalligan.org/

The Conversation. (2025). https://theconversation.com/meta-is-abandoning-fact-checking-this-doesnt-bode-well-for-the-fight-against-misinformation-246878

LSE Impact Blogs. (2025). https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2025/01/14/do-community-notes-work/

Nadia Jude, Ariadna Matamoros-Fernández. (2025). Community Notes and its Narrow Understanding of Disinformation, TechPolicy.press: https://www.techpolicy.press/community-notes-and-its-narrow-understanding-of-disinformation/

Aim Sinpeng (University of Sydney), Fiona Martin (University of Sydney), Katharine Gelber (University of Queensland), and Kirril Shields (University of Queensland) (2021). Facebook: Regulating Hate Speech in the Asia Pacific. https://r2pasiapacific.org/files/7099/2021_Facebook_hate_speech_Asia_report.pdf

Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology. (2025). Meta is abandoning fact checking – this doesn’t bode well for the fight against misinformation. https://www.qut.edu.au/news/realfocus/meta-is-abandoning-fact-checking-this-doesnt-bode-well-for-the-fight-against-misinformation

Ahmar “Sunny Boy” Mahboob. (2023). Writings on Subaltern Practice. (p.15) https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-43710-6

Be the first to comment