It’s not about the clothes

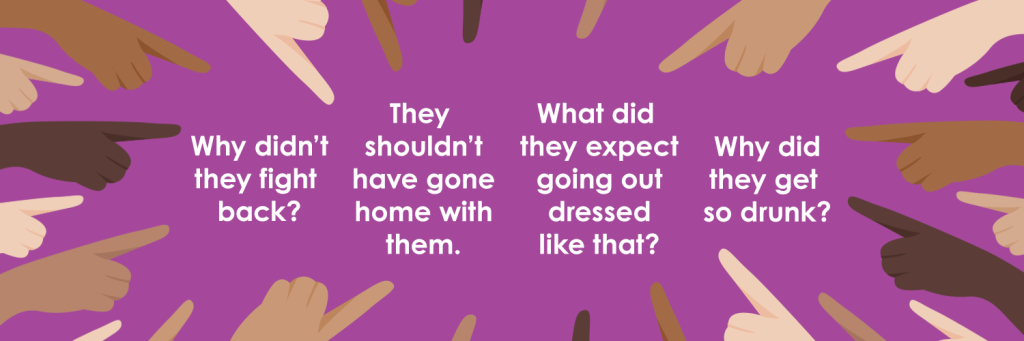

In conversations about sexual harassment or assault cases, have you ever heard someone respond, ‘What was she wearing?’. This question, as noted by the Sexual Assault Centre of Edmonton (SACE), is commonly heard around the world, both online and offline (SACE, 2024). This kind of comment is not only rude but also harmful. It puts the blame on the victim instead of the person who did something wrong. Sadly, this way of thinking is still common in many places.

You might not realize it at first, but blaming someone for what they wear isn’t just unfair, but it’s a form of hate speech. It eternalizes the harmful concept that women must wear specific dress codes to avoid harassment, suggesting that if they do not, they are somehow to blame. However, no one ever deserves to be harassed, regardless of their clothes.

As cited in Flew (2021), Parekh defines, “Hate speech is speech that discriminates against individuals based on an arbitrary and normatively irrelevant feature, stigmatizing them and legitimizing hostility towards them”. This illustrates how victim-blaming, as a form of hate speech, harms not just the individual but also fosters negative attitudes toward entire groups. It is crucial to understand why it needs to stop and find practical steps to prevent its continuation in society.

The rise of digital victim-blaming

Blaming victims in sexual harassment or assault cases is a symptom of a much bigger problem. It shows how society often ignores harmful and discriminatory ideas, especially in the digital platforms. With platforms like Facebook and Tiktok treated as the main stage for conversations today, it is no surprise that hate speech, even in sneaky forms like victim-blaming, is rising.

According to the 2021 Facebook Asia Hate Speech Report, platforms like Facebook are not just fueling the fire when it comes to stopping this kind of talk. They might be making it worse. In places where content moderation is weak, especially in non-English languages, these toxic beliefs spread fast. Comments blaming victims for what they were wearing or where they were at the time are everywhere, and they arere being left completely unchecked online.

As Parekh (2012) pointed out, researchers have been warning us for a long time that hate speech is not always loud and obvious. Sometimes, it hides behind “concerned” questions or moral judgment. Moreover, as scholar Bhikhu Parekh puts it, hate speech often paints a group with negative stereotypes, making them seem like a threat or a problem. Victim-blaming fits right into that pattern. It chips away at people’s dignity and pushes the idea that harassment or assault is somehow their fault.

Until social media platforms genuinely step up with clear guidelines and follow through on enforcing them, not just with fancy algorithms but with real human oversight, these toxic narratives will always be there. You will find them in comment sections, direct messages, and many viral posts. Unfortunately, the problem does not stop there. When harmful ideas like victim-blaming are left unchecked, they do not just stay online, but they seep into everyday life, fueling old stereotypes and reinforcing mindsets that continue to harm real people in the real world.

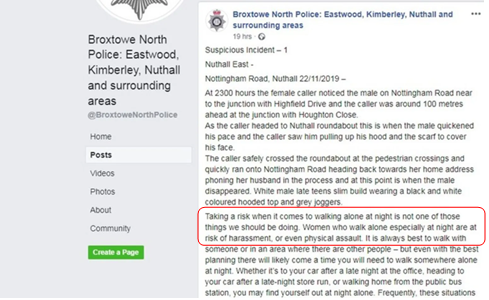

The Nottinghamshire Police Facebook post

A relevant example of victim-blaming can be seen in Nottinghamshire Police Facebook post in November 2019. It faced criticism for a Facebook post that was perceived as victim-blaming. The post suggested that women should not walking alone at night to stay safe from harassment or assault. On the surface, it might have sounded like a standard safety tip. However, for many, it hit a nerve because instead of addressing the people who commit these acts, it placed the burden of prevention on potential victims.

This post led to public backlash. A lot of people were criticizing the message for pushing harmful stereotypes and shifting focus away from the real problem, which is the perpetrators. What made the whole situation even more frustrating is that Facebook claims that they stand against hate speech and gender-based harm. Facebook’s Community Standards clearly says that they ban content targeting people based on gender or spreading toxic stereotypes.

Although the police post did not write hateful language, it still fed into a damaging narrative, in which women are somehow responsible and deserved for what happens to them. That kind of messaging does not just hurt, but it makes survivors question whether they will be blamed if they experience harassment and speak up.

Moreover, a study published in 2023 in Computers in Human Behavior found that when people witness online harassment, they are less likely to help if the victim is wearing something perceived as “sexualized.” In other words, people are more likely to blame the victim based on appearance alone, which shows just how deeply victim-blaming attitudes can run in digital platforms.

Eventually, the police removed the post, but only after gaining public attention. Imagine if the post had not gone viral, it would have stayed up and unchallenged, which can normalize victim-blaming. This moment is a reminder that silence online does not mean safety, however, it often means passive acceptance.

This case shows just how big the gap is between what huge platforms like Facebook claim to stand for and what they allow to happen. The 2021 Facebook Asia Hate Speech Report pointed this out loud and clearly, saying that moderation is inconsistent, especially when the harm is not obvious. The post framed as “helpful advice” can still do real damage. If we are serious about tackling hate and discrimination online, then even well-meaning institutions need to be held to the same standard. When harmful ideas go unchecked, they do not just stay on the internet. They shape how we think, talk, and treat each other in real life too.

Victim-blaming on TikTok in Indonesia

This disconnect between what platforms promise and what they enforce is not only in the English-speaking countries. According to Statista, Indonesia is one of the top five countries with the highest number of internet users.

With such a large and active online population, the country also faces growing concerns around victim-blaming. On TikTok, a platform designed to inspire creativity and self-expression, the experience can be very different for women. Those who post dance videos often find themselves on the receiving end of body-focused, objectifying comments. Their performance is often dismissed, with attention placed more on the body than talent. When harassment happens, the blame often falls on the creator.

One of the members of a small Indonesian idol group Kalopsia, known as @kalopsia_pewlin on TikTok, has shared her experience dealing with this kind of online harassment. She regularly posts dance videos and cosplay photos as part of the group’s anime-inspired persona. But sadly, her content often attracts inappropriate comments.

In the video above, she revealed some of the disgusting messages that she received, like “Pink tuh pasti” (which basically means “Your vagina must be pink”), “Spill Tesla’s logo” (a slang way of saying “show your private parts”), and “Please say ‘Yamete.’” The word “Yamete” in Japanese simply means “stop,” but in this context, it’s often used in adult anime or sexual content where it’s said in a moaning tone. It’s a clear example of how fun, expressive content can be met with disrespectful and sexualized behavior that crosses the line.

But again, people ask why she wore certain clothes or chose that dance style, as if those choices justify the abuse. In a country with such a massive and active online population, the impact of these narratives is significant. When they go unruled, they do more than reflect harmful beliefs. Moreover, they contribute to normalizing such behaviors.

What happened to Pewlin isn’t something new, in fact, many women in Indonesia face the same things, both online and offline. According to a Kompasiana article that refers to Catatan Tahunan (CATAHU) by Komnas Perempuan, which is Indonesia’s National Commission on Violence Against Women, cases of sexual violence against women went up by a shocking 792% between 2008 and 2019. That number alone is already alarming.

A separate study by Lentera Sintas Indonesia, a survivor-led nonprofit that supports people who’ve experienced sexual violence, found that 93% of survivors never report what happened to them because they’re scared of being blamed, judged, or not taken seriously. That’s why Komnas Perempuan says the reported cases are just the tip of the iceberg. Behind every stat, there are so many stories that stay unheard because people don’t feel safe speaking up.

When survivors are met with judgment instead of support, it doesn’t just cause emotional harm. It creates a culture where silence and shame thrive. And when platforms allow these kinds of messages to spread unchecked, they’re helping that culture grow. This is a heartbreaking reality that shows just how deeply rooted rape culture and victim-blaming still are, and how much work we still must do to create safe, supportive systems that truly listen to survivors.

Challenges in regulating hate speech

One of the biggest challenges in stopping hate speech and victim-blaming online is that it doesn’t always look like hate at first glance. As Terry Flew explains in his book Regulating Platforms, not all harmful speech comes in the form of loud insults or threats. Sometimes it’s hidden in things like jokes, sarcastic comments, or “advice”.

A lot of platforms rely on automated tools to catch harmful content, but these systems are mostly built to understand English. The problem is, even in English, these tools often miss some words that have hate speech because they can’t fully understand cultural context or the subtle ways harm can be expressed. Moreover, since the internet is global, many posts are also written in other languages or include cultural references that these systems cannot recognize at all.

As a result, a lot of harmful content slips through unnoticed. Even when human moderators are involved in the review process, many are not trained well enough to understand local issues and context, especially when it comes to gender-based harm. That leads to moderation that feels inconsistent, unfair, and disconnected from the realities people face in different parts of the world.

Flew (2021) also points out a tough reality for platforms like Facebook and TikTok by saying that they’re trying to protect free speech, but they also need to stop content that spreads hate or discrimination. This creates a tricky balance. Sometimes, platforms avoid removing harmful posts because they’re worried about being accused of censorship. But when that happens, content like victim-blaming gets to stay up and keep spreading widely. Consequently, a lot of harmful narratives stay online and continue to shape how we talk, think, and treat others both on the internet and in real life.

So, what can we do about it?

Solving the problem of hate speech and victim-blaming online isn’t just a one-night task and the job of one group. It surely needs action from platforms, governments, and internet users as well. As Terry Flew points out in his book, social media companies need to take more responsibility. It’s not enough to say they support free speech. They also must ensure their platforms don’t become a space where harmful ideas go unreviewed. This means improving their moderation tools, so they work better in different languages and cultures, and hiring moderators who understand local issues, especially around gender and discrimination.

The 2021 Facebook Asia Hate Speech Report also highlights the need for more training, better systems, and clearer rules on what kind of content should be removed. In addition, governments can help too by creating fair and balanced rules that protect people from harm without limiting healthy discussion. They can push platforms to be more transparent and do regular checks to ensure their policies are working. Not only that, internet users, or netizens, have a huge role. We can speak up when we see victim-blaming, support survivors, and hold platforms accountable when they fail to act. Real change starts with all of us, and even small actions online can help create a safer space for everyone.

Conclusion: Reclaiming online space

All in all, victim-blaming is not just a small issue, but it’s a harmful mindset that gets louder when platforms like Facebook and TikTok don’t take serious steps to stop it. Yes, they do have rules against hate speech, but the way those rules are implemented doesn’t always match what they promise us. A lot of harmful posts still spread widely, especially when they are not in English or when the tone is not obvious. Even human moderators sometimes miss some words because they do not fully understand the culture or issue being discussed.

Platform companies need to do better by improving their tools, training moderators more seriously, and making sure harmful content does not go unchecked. Governments can also step in to make sure these companies are doing their job well. And as internet users, we have power too. When we call out harmful comments and support victims when something feels wrong, we help shape the internet into a safer space.

Remember, big changes take time, but small actions really do matter. If we want online spaces to become healthier and safer, it starts with all of us choosing not to stay silent.

References:

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating Platforms. Polity Press.

Hateful Conduct | Transparency Center. (2022). Meta.com. https://transparency.meta.com/en-gb/policies/community-standards/hateful-conduct/

Kompasiana.com. (2021, January 16). Pelecehan Verbal di Media Sosial Menormalisasi Victim Blaming dan Rape Culture. KOMPASIANA. https://www.kompasiana.com/candyaupavata2496/6002223e8ede485cee569f85/pelecehan-verbal-di-media-sosial-menormalisasi-victim-blaming-dan-rape-culture

Nottinghamshire Police “victim blame” women in Facebook post. (2019, November 27). BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-nottinghamshire-50565663

Petrosyan, A. (2023, August 30). Countries with the largest digital populations in the world as of January 2023. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/262966/number-of-internet-users-in-selected-countries/

Reuters. (2016, July 26). Survei: 93 Persen Kasus Pemerkosaan di Indonesia Tidak Dilaporkan. VOA Indonesia. https://www.voaindonesia.com/a/survei-93-persen-pemerkosaan-tidak-dilaporkan/3434933.html

SACE. (2022). Victim Blaming. Sexual Assault Centre of Edmonton. https://www.sace.ca/learn/victim-blaming/

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021, July 5). Facebook: Regulating hate speech in the Asia Pacific. Final Report to Facebook under the auspices of its Content Policy Research on Social Media Platforms Award. Dept of Media and Communication, University of Sydney and School of Political Science and International Studies, University of Queensland. https://r2pasiapacific.org/files/7099/2021_Facebook_hate_speech_Asia_report.pdf

Wang, C., Yu, Y., Zhang, X., & Zhang, X. (2023). The influence of victim self-disclosure on bystander intervention in cyberbullying. Computers in Human Behavior, 143, 107710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107710

Be the first to comment