Introduction

Hate speech has long been lurking in interpersonal exchanges, and with the rapid development of the digital age, such speech has gradually evolved into online victimization and even verbal abuse, and the scope and nature of hate speech have changed dramatically. More and more people feel that it is not legally regulated to attack others indiscriminately online, which has led to the prevalence and breadth of the hate speech problem on every social platform. As Flew states, “Online hate speech and its amplification through digital platforms and social media have been identified as significant and growing issues of concern.” (Flew, 2021) The major social platforms allow every user to be a consumer and producer of content, so hate speech can be widely disseminated in mainstream media.

Features of digital platforms also contribute to the proliferation of hate speech. First is the algorithmic recommendation system, “The architecture of social media platforms is designed to maximize engagement, often by promoting content that is emotionally provocative or extreme, which can contribute to radicalization.” (Carlson, B., & Frazer, R., 2018) This statement points out that the platforms’ recommendation mechanisms tend to promote emotionally inflammatory and radical content, thereby increasing user engagement and eliciting radicalizing emotions such as empathy or disdain. Second, “Anonymity, or at least the perception of anonymity, also facilitates mobbing, as users may feel less personally accountable for their actions.” (Carlson, B., & Frazer, R., 2018) The ‘anonymity’ provided by the online environment provides a layer of protection for users to express aggression, in which they feel less personally accountable for their actions, which in turn evolves into to engage in such hate speech with impunity. Finally, the echo chamber effect of the platform allows users to be constantly exposed to information that agrees with their views, reinforcing cognitive bias. “Echo chambers allow users to receive only affirming information, reinforcing their existing views and contributing to increased polarisation.” (Carlson, B., & Frazer, R., 2018)

In addition, it is important to note that hate speech is no longer just an individual-to-individual attack, but is now expanding into a ‘group expressive attack’, specifically A large number of users are attacking an individual or a group of individuals at the same time. At the same time, this type of speech has become more subtle and systematic, ranging from overt attacks to subtle expressions, such as those disguised as humor, sarcasm, stylized images, or the use of acronyms. These forms are more difficult to detect and regulate, but they are equally destructive, especially when they accumulate over time or become normalized within certain communities. “Hate speech does not in itself incite to public violence, …its racist and similar arguments are often couched in ‘scientific’ language or presented as jokes or as ironic commentary.” (Flew, 2021)

Against this background, the prevalent development of a star-chasing culture has further provided a new environment for hate speech. The increasing frequency of online interactions among fan groups has given rise to a unique community ecology, and has contributed to the continuous spread of hate speech between idols and fans, different fan groups, and even fans and non-fans, reinforcing group rivalries and stereotypes, and thus triggering conflicts in reality. In this blog, I aim to explore how star-chasing culture has become a hotbed for hate speech on social platforms, and use Weibo as the main case for analysis.

Hate Speech in Fandom Wars

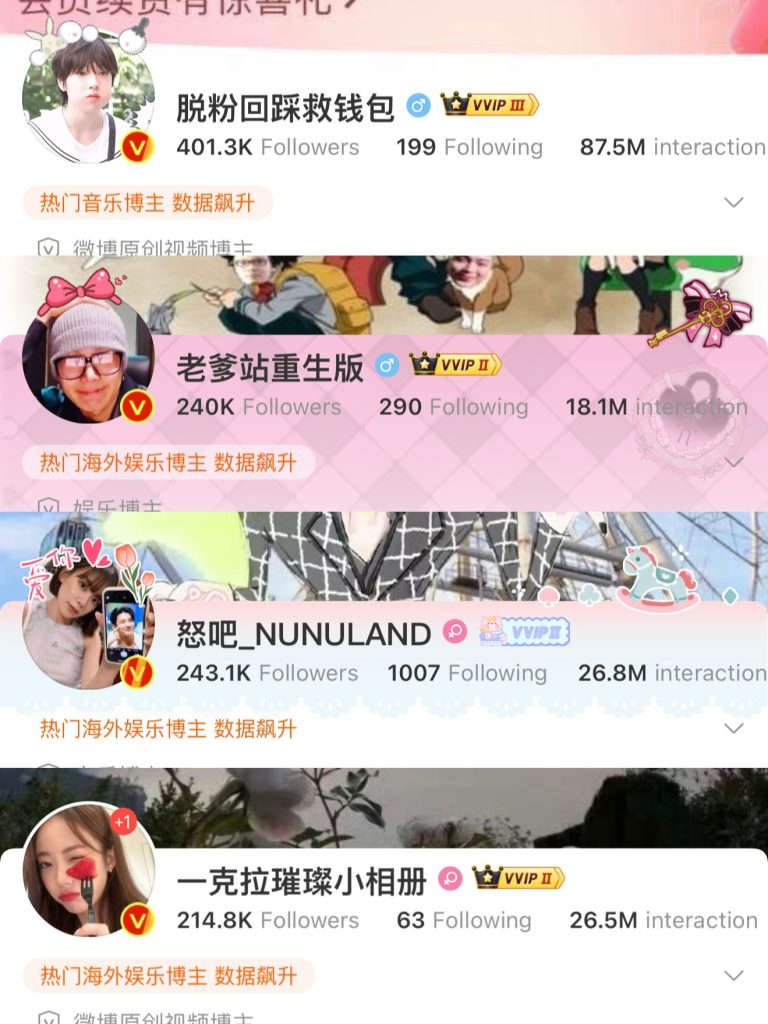

As I said above, hate speech is now evolving into a form of group attack. There are accounts on Weibo that are either co-managed by a small group of people (maybe about 5-10) or are managed by bots that automatically post offensive and bigoted content to generate traffic and cash in on it. Such accounts were originally called bots and were initially used to dilute negative comments about celebrities, create neutral public opinion noise, and also include controlling comments in public squares. But now they are called “toilets”, and we all know that toilets in real life are very dirty and messy, and are used for defecation, which is a metaphor for accounts like these that are too dirty and offensive, causing them to become a place where fans can “defecate uncontrollably”. According to figure 2, the typical accounts I found from Weibo (since Weibo is a Chinese platform, the display is in Chinese), you can see that each account has a lot of fans, and a lot of retweets, comments, and likes, and there is a huge amount of traffic from just four accounts, which shows how much exposure a piece of content can get. How high the exposure of a piece of content can be.

The use of bot in fandom hate reveals a layered governance problem: the failure of platforms to manage the infrastructural drivers of such hostility. As Woods (2021) argue, “regulation should require platforms to assess and mitigate systemic risks arising from the design of their services, including the algorithmic amplification of harmful content”, rather than focusing solely on individual user content. Weibo’s algorithm is designed to reward engagement—likes, reposts, and comments—regardless of whether such engagement is driven by constructive or viral hate. As a result, provocative or divisive bot posts tend to receive more exposure, pushing hate hate toward the level of subjectivity.

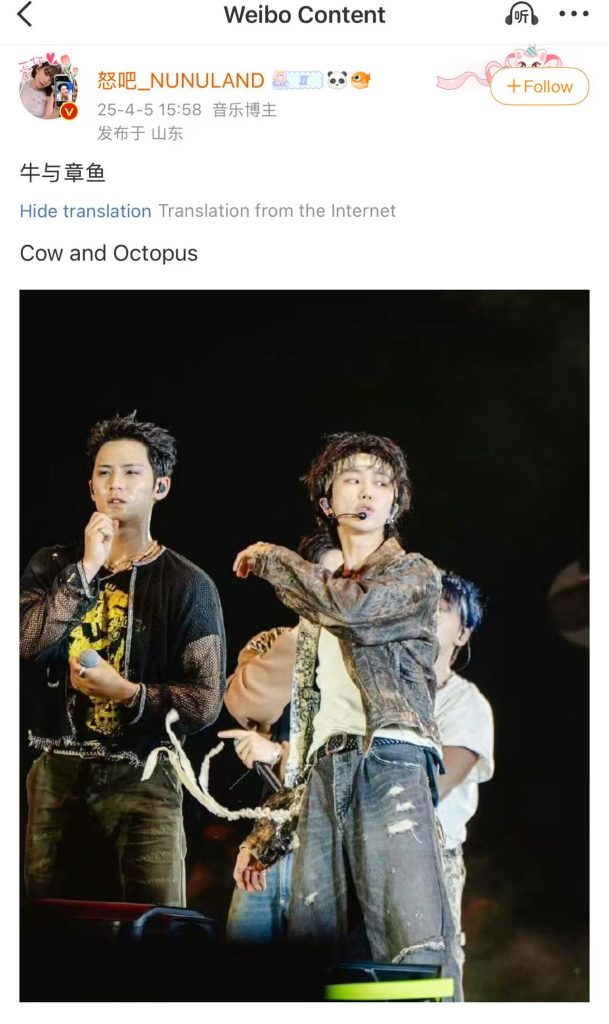

From figures 3 and 4, we can see that such accounts are full of attacks on idols from different groups. Figure 3 regards celebrities as animals, which is a very impolite description in China. Hate speech like this is a metaphor hidden in the text. Looking at figure 4, the celebrity’s face and hairstyle are regarded as big toes, which is also insulting the celebrity’s appearance. Another comic picture is also posted, and the intention of expressing hate speech is to satirize the two people’s similar appearance. We can also see that the anonymity of this account is more hidden than posting on the Internet by yourself, because the administrator posts by submission, and each post is sent by the same account. No one knows who submitted the post except a small group of people or robots who manage the account, and there will be no clues to find the original contributor. Such a private method allows more people to submit hate speech, because it will minimize their own responsibility and will not receive any negative feedback.

Some people may think that this phenomenon is just a common behavior in the fan ring: because an artist is in a competitive relationship with the idol they are chasing, they take the opportunity to vent their dissatisfaction, and it is difficult to define whether it constitutes hate speech. We must admit that the boundary between “violent expression” and “hate speech” is becoming increasingly blurred. In many cases, “violent expression” is even used as an excuse to cover up hate attacks. However, the content shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4 has clearly exceeded the scope of emotional expression. It contains personal attacks and is obviously inflammatory and harmful. It can be defined as hate speech. In contrast, the real “violent expression” is usually only manifested as a strong emotional tendency. For example, in the star-chasing culture, fans may fiercely criticize certain behaviors of idols, or express dissatisfaction with the quality of a certain work. Although such remarks are fierce in tone, they do not directly infringe on the personal dignity of others, nor do they have violent tendencies.

“It is crucial to recognize… that online communication is frequently and increasingly multimodal, rather than monomodal.” (Ullmann & Tomalin, 2019) This is exacerbated by the fact that hate speech is often more difficult to be identified by automatic moderation systems. As mentioned above, hatred is no longer limited to explicit offensive language, but appears in the form of memes or “humorous” images, which require in-depth cultural understanding to accurately interpret. Although such expressions cleverly evade the platform’s censorship mechanism, they still cause real psychological trauma and social exclusion to individuals. In fan culture, such hate speech is closely linked to youth digital culture and emotional investment. Fans are mostly teenagers or young people, and their identity is often based on a sense of belonging to a community. In this context, attacks launched through “bot armies” not only intensify online hostility, but also gradually distort young people’s perceptions of conflict resolution, justice and expression. Platform mechanisms tend to amplify emotional content and reward users who “shout the loudest” or “post the fastest”, rather than encouraging rational dialogue and constructive interaction. This ecology not only threatens the public civilization of the digital space, but also imposes a profound psychological burden on young users who are involved in it for a long time.

From a governance perspective, the existence of these “toilet” accounts on Weibo indicates a serious failure to implement an effective digital policy. Despite China’s strict regulation of cyberspace, Weibo remains under-regulated in the fan community due to its commercial value. Bots generate traffic, and traffic generates revenue for the platform. This misalignment of incentives leads to what Matamoros-Fernández (2017) calls “platform hate”-the combination of platform architecture, economic logic, and user behavior that sustains online hostility.

To address this, we must rethink digital governance. First, platforms need to more clearly define and coordinate detection systems for account behavior. Second, algorithms must be redesigned to de-prioritize emotionally manipulative content and reduce incentive structures that reward mob behavior. Third, user education campaigns-especially within youth-oriented platforms-should promote digital literacy about the dangers of platform hate. As Carlson and Frazer (2018) note, users often perceive hate as an “unconscious” behavior. Digital policy and governance must therefore move beyond surface-level content bans and adopt the duty of care model suggested by Woods. This includes investing in proactive detection of botnets, increasing the transparency of recommender systems, and providing grievance mechanisms for users targeted by coordinated hate.

In addition, user education is crucial. Many young fans participate in cyberattacks without realizing the impact. Today’s digital engagement is closely linked to identity performance. For many young people, cyberattacks are not just malicious, but also part of loyalty, belonging and emotional expression. Public awareness campaigns can help redefine what it means to be a “true fan” – not someone who defends their idols through hate, but someone who fosters respectful discourse.

Finally, digital policies must strike a balance between regulation and speech rights. International frameworks such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights recognize both the right to freedom of expression (article 19) and the obligation to prohibit hate speech (article 20). Governance models must follow this line: they should not criminalize disagreement or satire, but must discourage the viral spread of organized digital hate, especially when it targets vulnerable groups.

Conclusion

The case of Weibo fan robots fully reveals the structural nature of hate speech in the digital age: it is no longer an isolated deviant behavior, but a product of the joint action of platform design, algorithmic mechanism and fan circle culture. From emotional content being amplified by recommendation algorithms to offensive accounts such as “toilet” manipulating public opinion and diverting traffic for monetization, hatred is not only allowed in this context, but also encouraged and systematically produced. In the star-chasing culture, attacks are often rationalized in the name of “eager to protect the master” or “expressing loyalty”, making the boundary between loyalty and hostility increasingly blurred.

Therefore, platform governance should go beyond the traditional logic of content deletion and turn to more forward-looking systematic intervention. Platforms such as Weibo need to implement the “duty of care”, reform the algorithm recommendation logic, reduce the visibility of offensive content, and establish a governance framework for community participation, such as introducing community auditors and enhancing reporting transparency. In addition, schools and institutions should be linked to promote digital literacy education for fan groups, guide users to understand the difference between emotional expression and hate attacks, and rebuild the boundaries of public expression.

Only by making simultaneous progress at the three levels of system design, cultural cognition and user education can the platform truly curb the spread of hatred in fan circles and reshape an emotionally rich but rationally controllable digital public space.

References

Bronwyn Carlson and Ryan Frazer. (2018). Social Media Mob: Being Indigenous Online. Macquarie University. https://research-management.mq.edu.au/ws/portalfiles/portal/85013179/MQU_SocialMediaMob_report_Carlson_Frazer.pdf

Chaudhary, M., Saxena, C., & Meng, H. (2021). Countering Online Hate Speech: An NLP Perspective. ArXiv:2109.02941 [Cs]. https://arxiv.org/abs/2109.02941

DUNN, P. (2024). <em>Online Hate Speech and Intermediary Liability in the Age of Algorithmic Moderation</em> [Doctoral thesis, Unilu – University of Luxembourg]. ORBilu-University of Luxembourg. https://orbilu.uni.lu/handle/10993/61876

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms . Polity Press.

Hietanen, M., & Eddebo, J. (2022). Towards a Definition of Hate Speech—With a Focus on Online Contexts. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 47(4), 019685992211243. https://doi.org/10.1177/01968599221124309

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: the mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1293130

Picture from The United Nations (Figure 1) https://www.un.org/en/hate-speech/understanding-hate-speech/hate-speech-versus-freedom-of-speech

Screenshots from the weibo (photoed by Luo, 2025). (Figure 2-4)

Ullmann, S., & Tomalin, M. (2019). Quarantining online hate speech: technical and ethical perspectives. Ethics and Information Technology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-019-09516-z

Wilson, R. A., & Land, M. K. (2020). Hate speech on social media: Content moderation in context. Conn. L. Rev., 52, 1029.

Woods, L. (2021). Obliging Platforms to Accept a Duty of Care. In Martin Moore and Damian Tambini (Ed.), Regulating big tech: Policy responses to digital dominance (pp. 93–109).

Zhou, E. (2013). Displeasure, star-chasing and the transcultural networking fandom. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=1e81458c597a98b87a00608deeb6567ed1e4546c

Be the first to comment