Introduction

On January 6, 2021, a crowd stormed the U.S. Capitol. The event was fueled in part by online hate speech, extremist rhetoric, and misinformation that simmered on social media platforms. Years of toxic online culture fueled the flames that erupted into real-world violence on Capitol Hill. The Capitol riot was not an isolated incident, but the culmination of trends in online behavior that people have been warning about for years. We’ll use the Capitol riot as a key case study to explore how hate speech and online harms escalate from the screen to the street. We need to rethink how we manage and moderate our digital public square. We’ll use research to understand how online hate thrives and why platform design matters.

The Problem of Online Hate Speech

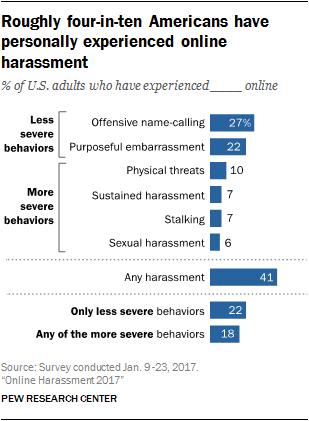

We can define hate speech as expressions directed at others based on innate characteristics such as race, religion, gender, or ethnicity, with the intent to demean or incite hatred (Flew, 2021, p. 115). Unfortunately, online platforms provide fertile ground for this toxic rhetoric. Media scholar Terry Flew notes that “online hate speech and its amplification through digital platforms and social media has been identified as a significant and growing problem” (Flew, 2021, p. 115). In fact, a 2017 Pew Research Center survey found that 41% of U.S. internet users had experienced online harassment and 18% had faced serious threats, including stalking and physical threats (Pew Research Center, 2017).

The chart is from the Online Harassment 2017 Pew Research

We should not see this as mere online drama, as legal scholar Danielle Citron says: “It is absurd that it is acceptable in a blog or forum speech to engage in behavior that would be considered hooliganism or illegal behavior in a public place” (Citron, 2014). The kind of hateful, toxic speech that would be completely unacceptable if shouted on a street corner is dangerously tolerated on internet platforms.

Beyond individual harassment, it silences marginalized voices and normalizes hostility toward targeted groups. In Australia, 88% of people have seen racism online, more than one in five have been threatened in person, and in 17% of cases, these online threats have spread offline and have had an impact on their lives (Carlson & Frazer, 2018, p. 13). Researchers note that experiences of online racism have “very real and often harmful effects” on people’s well-being (Carlson & Frazer, 2018, p. 13). Hate speech is more than “words”; it causes psychological harm, erodes people’s sense of safety, and can inspire others to commit violence. There is often a dangerous continuum at work, where seemingly harmless jokes or memes in online communities can morph into extreme dehumanization that leads to real-life harm. Hate speech itself may not directly incite violence, Frew observes, but “the two are often linked” (Frew, 2021, p. 116).

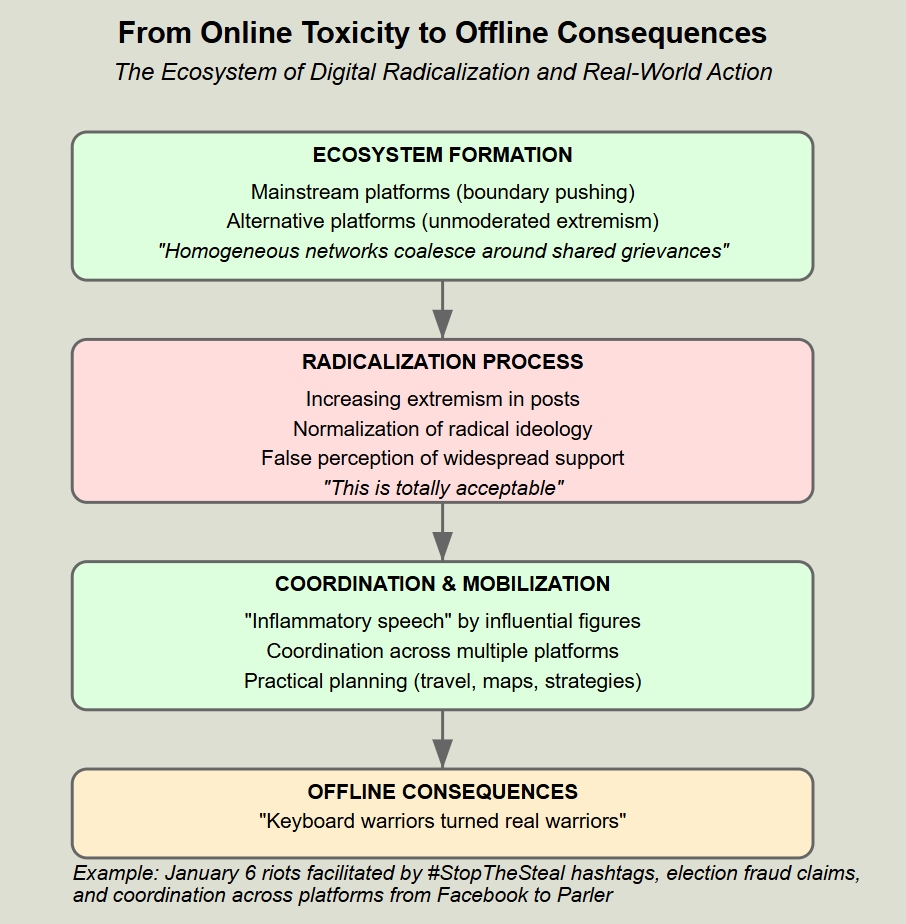

From online toxicity to offline consequences

The roots of the riots are an ecosystem. On mainstream platforms, they often push the boundaries of content policies, while on alternative platforms with more relaxed rules, they operate normally. The result is an echo chamber of extremism. Social networks allow what one research team calls “homogeneous networks to coalesce around shared grievances,

” which “further promotes groupthink and normalizes radical ideology” (Mønsted et al., 2017).

On the same online hate forums, people incite each other, with each post more extreme than the last, until action becomes not only justified but necessary.

In the weeks leading up to January 6, hashtags like #StopTheSteal became trending topics, and false claims of “election fraud” spread rapidly on platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and more. Far-right groups used these platforms as organizing tools. They coordinated travel plans, shared maps of Washington, D.C., and hyped up the confrontation. Media researcher Joan Donovan describes this phenomenon as “inflammatory speech,” which is essentially influential figures using social media to incite mass violence (Donovan, 2021). According to Donovan, “inflammatory speech involves insurgents communicating across multiple platforms to direct and coordinate social movements to mobilize” (Donovan, 2021). Many people post in real time as they breach barricades, and their digital echo chambers convince them that they are patriots doing what everyone online wants them to do. Sadly, they have become keyboard warriors turned real warriors.

Why do so many people have the courage to move from hate posts to criminal behavior? When users see others sharing extremist memes or making violent statements, they develop a false sense that these views are normal and widely supported. As Citron says,

“If you feel like you’re in a group and people are behaving in a very extreme way, you think, hey, everyone else is doing it too. This is totally acceptable” (Citron, 2014).

Online hate forums can thus serve as engines of radicalization, lowering social taboos and amplifying anger. On January 6, President Trump tweeted a call for supporters to come to Washington for a “crazy” protest, and tens of thousands of people prepared to respond. They were prepared because they were inspired by the election conspiracies, radical rhetoric, and open calls for violence that were circulating on platforms from Facebook to Parler.

Platform Culture and Amplification: Why Design Matters

Platforms often tout themselves as open, neutral venues for free expression. However, their architecture actually influences user behavior in profound ways. As technology policy experts Lorna Woods and William Perrin observe, “social media platforms are not neutral to the flow of information through their design choices” and in fact “play a role in the creation or exacerbation of problems” (Woods & Perrin, 2021, p. 99), such as hate speech.

Algorithms that maximize engagement often elevate provocative and extreme content because it attracts attention (outrage = clicks). Recommendation systems can lead users down “rabbit holes”—watch one conspiracy video and the platform recommends the next, more extreme one. Social media companies’ measures of success (time on site, shares, likes) don’t distinguish between cute cat videos and neo-Nazi propaganda; if it keeps you online and engaged, it gets promoted.

These platforms foster a “toxic tech culture”—an online network filled with hate, exclusion, and offensive values (Massanari, 2017, p. 334). Massanari uses the term to describe communities that “rely heavily on implicit or explicit harassment of others” as a mechanism for connection (Massanari, 2017, p. 334). These toxic cultures are the breeding ground for events like January 6, where sexism, racism, and hyperpartisan anger converged.

The problem is also exacerbated by how platform policies are enforced. For years, social media companies have taken a largely hands-off approach to moderators in the context of free speech, arguing that more speech is better. Yet this approach has allowed hate and abuse to flourish, often drowning out the voices of women, minorities, and other targeted groups who then exit for their own safety. In particular, after the Capitol riot, platforms began to crack down, banning certain extremist accounts and improving hate speech detection. But these moves have been reactive and inconsistent. Toxic communities tend to migrate to more tolerant platforms, creating a whack-a-mole situation.

The deeper problem, as scholars like Matamoros-Fernández have argued, is that the culture of the platforms themselves must change. She coined the concept of “platform racism,” which is fundamentally influenced by social media design and policy (Matamoros-Fernández, 2017 p. 931). In her words, “platform racism” is “a new form of racism that emerges from the culture of social media platforms and the specific culture of use associated with them” (Matamoros-Fernández, 2017, p. 930). This means that in order to combat online hate, platforms cannot just blame a few bad apples. They must examine how their own characteristics, such as anonymity, virality, and lack of moderators, allow hate to spread.

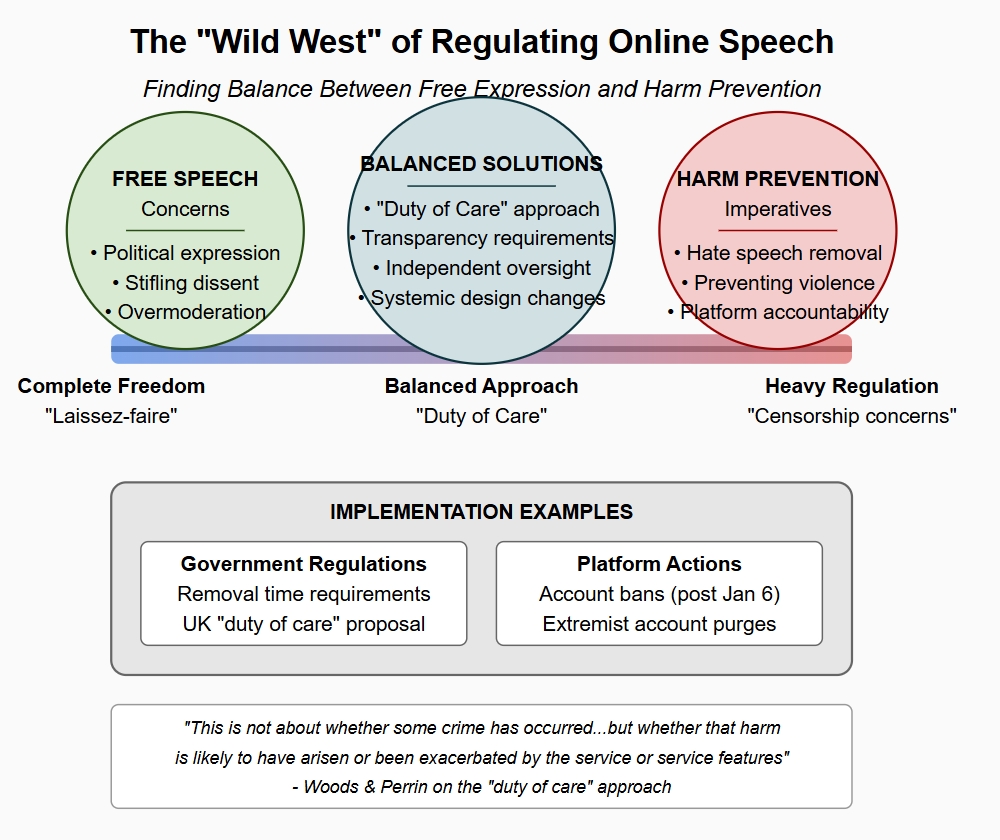

The “Wild West” of Regulating Online Speech

Relying solely on platform companies to self-regulate is problematic, as they often act too late or only in response to public pressure. Governments and policymakers have begun to weigh in, discussing regulations to make social media safer. In some countries, laws now require hate speech to be removed more quickly. In the UK, academics and regulators have floated the idea of imposing a “duty of care” on platforms to their users. As described by Woods and Perrin, a duty of care approach would legally require platforms to proactively identify and mitigate risks of harm on their services (Woods & Perrin, 2021, p. 94). Importantly, they emphasize that this is about systemic change, not just chasing after individual bad posts. Woods and Perrin note that the duty of care

“is not about whether some crime has occurred…but whether that harm is likely to have arisen or been exacerbated by the service or service features” (Woods & Perrin, 2021, p. 99).

Platforms need to build safer products from the ground up.

Of course, there’s a balancing act here. Free speech is a core value, and there are real concerns that excessive moderation or laws could suppress legitimate expression or political dissent. Any regulation must carefully weigh the right to free speech against the real dangers of unchecked online hate. Many experts believe that transparency and accountability are key. Platforms should be transparent about how they moderate content and how their algorithms work. They may need to provide data to researchers and auditors to ensure that they are not overly suppressing certain political viewpoints or failing to effectively curb hate. Independent oversight could help keep platforms in check. As one senator told tech CEOs after the 2016 election controversy, “You created these platforms, but they are abused…you have to take action” (Flew, 2022, p. 60).

We did see platforms “do some” unprecedented things after the Capitol riot, with Twitter and Facebook banning accounts of a sitting U.S. president that incited violence and thousands of extremist accounts being purged. This has sparked its own debate, but it sent a clear signal that the era of completely laissez-faire social networks is over. Terry Flew describes this as “the end of the Libertarian internet,” acknowledging that some rules and governance are needed in online as well as offline societies (Flew, 2022, p. 32). The challenge now is to find the right mix of solutions to curb the worst harms without stifling the open exchange of ideas that makes the internet valuable.

In conclusion

The lesson of the Capitol riot is that we must take online hate and extremism seriously. It’s not just the internet, it’s part of the fabric of modern public life. Social media platforms need to do more to moderate content and redesign the systems that currently facilitate extremism. Users need better tools and norms to deal with hate speech. Policymakers must ensure there are guardrails so that social media doesn’t become a lawless Wild West, but a space where basic standards of decency and safety apply.

Upholding free speech doesn’t mean allowing any and all speech, no matter how harmful. Just as we have laws against incitement and threats in the offline world, we need norms and rules for the online world that protect us from the most dangerous abuse. The stakes are high in rebuilding a healthier online ecosystem, but so is the resolve of those working to curb online hate. If we learn the lessons of January 6, we may be able to stop the next tragedy before it begins with a post or a tweet.

Reference

Carlson, B., & Frazer, R. (2018). Social media mob: Being Indigenous online. Macquarie University.

Citron, D. K. (2014). Hate crimes in cyberspace. Harvard University Press.

Donovan, J. (2021, January 6). Networked incitement. Scientific American.

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/networked-incitement

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. Polity Press.

Mønsted, B., Sapieżyński, P., Ferrara, E., & Lehmann, S. (2017). Evidence of complex contagion of information in social media: An experiment using Twitter bots. PLOS ONE, 12(9), 1–23.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184148

Woods, L., & Perrin, W. (2021). Obliging platforms to accept a duty of care. In M. Moore & D. Tambini (Eds.), Regulating big tech: Policy responses to digital dominance (pp. 93–109). Oxford University Press.

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: The mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930–946.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1293130

Pew Research Center. (2017). Online harassment 2017.

https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2017/07/11/online-harassment-2017

Be the first to comment