Retrieved from Pinterest.com

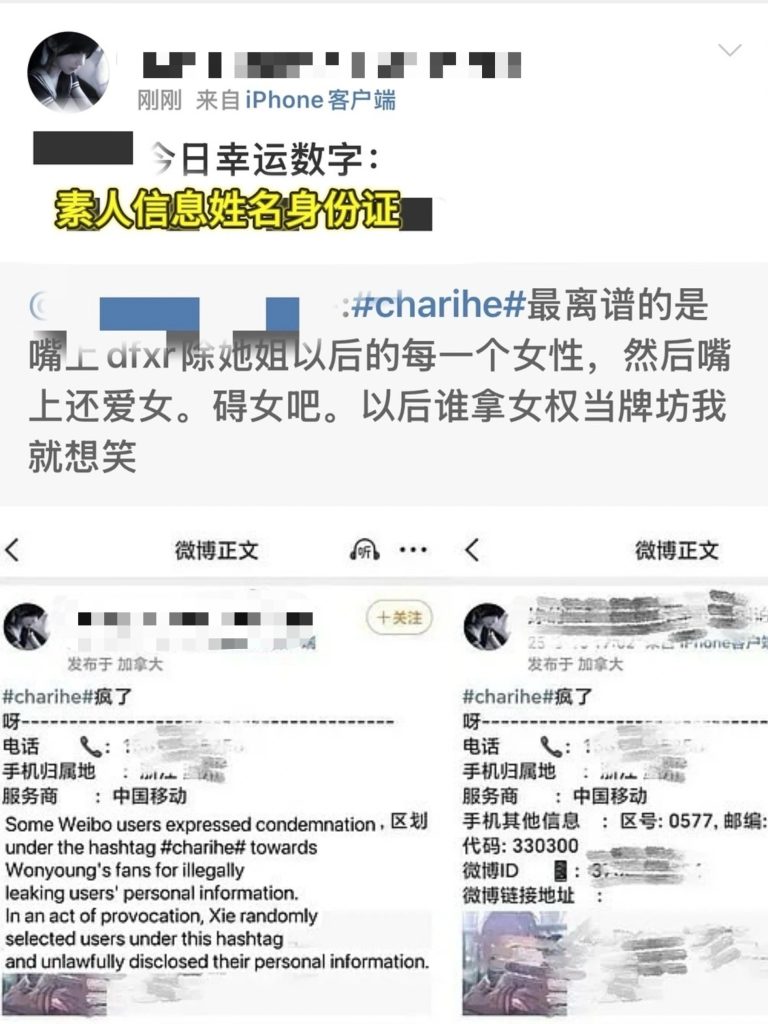

“With a single comment you make on the Internet, others can know who you are, know your cell phone number, workplace and other sensitive information, and even suffer offline harassment.” This is not the plot of a sci-fi movie, but a real incident. 2025 March, a pregnant Chinese netizen posted a neutral comment on Weibo about Korean star Jang Won-young, but because of the tone of voice “not enough respect” was attacked by some of her fans, one of them named “your eyes are the smallest lake in the world” account directly and maliciously exposed her name, ID card, phone number and unit information – and the owner of this account – is a 13-year-old girl.

In the digital era, violence no longer requires fists, it can be a string of retweets, a screenshot, or a privacy-leaking post with thousands of likes. Privacy violence is not something new in the disputes of the fandom and online communities, but in this case, what is most alarming is the trend of the low age of the “doxxing” behavior, the extremely low threshold and cost, as well as the collective absence of platforms and families in the supervision. When a child can manipulate technology tools to hurt others at will, we can’t help but question whether we are living in a digital system that defaults to violence?

In this article, we will use this incident as a starting point to explore how “doxxing” is amplified in the vacuum of algorithmic mechanism, online community culture and system, why even minors can easily commit privacy violence, and why platforms, laws and society collectively lose their voices in the blurred boundaries. We must face up to the fact that cyber violence is never just a technical problem, it is the result of everyone’s default indifference and acquiescence.

What is Doxxing? Unpacking Digital Vigilantism

The word “开盒”, which first originated in Chinese Internet communities, refers to the act of shaming or retaliating against another person by publicizing the private information. In the international context, it is known as “doxxing”. doxxing is a complex process of harassment that involves not only the invasion and exposure of another person’s privacy, but is also often accompanied by a call to action that incites both online and offline attacks (Eckert & Metzger-Riftkin, 2020). Unlike the early days of “human flesh search”, which required complex tools, today’s “doxxing” has a very low threshold. A 13-year-old girl can easily access and publicize the personal information of many netizens through social media and search channels. As mentioned by Lee (2022), “doxxing” relies on intertextuality, which is the collection and integration of information from various sources, including your social media profiles, personal blogs, websites, and even offline documents. So doxxing is not a hacking technique, but rather “information re-contextualization” that can be done by normal users. In addition, the platform’s default finding and republishing mechanisms are also a breeding ground for the proliferation of “doxxing” (Eckert & Metzger-Riftkin, 2020). What is more noteworthy is that in online community disputes, “doxxing” is often cloaked in the guise of “delivering justice”, while perpetrators claim to be “acting on behalf of Justice”. As Lee (2022) points out, perpetrators often rationalize their actions through “narratives of justice”, and most abominably, perpetrators often portray themselves as victims or heroes. However, the harm caused by violence to victims is real, Anderson and Wood (2022) emphasize that the doxxing is a “virtualized violence”, and its harm is structural, continuous, and multilayered, and even when the incident subsides, the information still exists in the network, and the psychological shadow caused by it is difficult to dissipate.

The 13-Year-Old Vigilante: A Case of Digital Vigilantism in China

In March 2025, a “doxxing storm” erupted on the Chinese social media platform Weibo. A pregnant netizen was attacked by some of the radical fans of South Korean artist Jang Won-young and her personal information was publicly exposed when she made a neutral comment about Jang Won-young’s itinerary. Netizens quickly realized that the perpetrator was suspected to be the daughter of Baidu vice president Xie Guangjun. This 13-year-old girl has long been involved in fandom battles, maliciously publicizing the private information of a number of netizens on the Internet and abetting the fanbase to unleash further cyber-violence against the victims. According to the victim’s description, after the incident, she developed a serious mental burden due to the privacy breach, “I was disturbed by the fact that as long as my comments made others feel dissatisfied, they could feel free to publish my information and lead others to cyber-violence against me.”

What is most ironic is that the girl also posted her father’s paycheck, home address and other private content when she attacked others – ultimately creating the absurd situation of “the doxxer being doxxed”. She responded in the comments section that she was in Canada, implying that Chinese laws and regulations had no effect on her, reflecting the “transgressive mentality” of some teenage users between technological empowerment and the legal vacuum.

Although Baidu Vice President Xie Guangjun subsequently apologized in social media, one of the victims said she did not recognize the apology, which she considered neither sincere nor factual, and she also raised questions about Baidu’s data security. At the same time, Baidu officials did not make a public response to public concerns about the source of the data, only the company’s intranet issued a “non-Baidu leaked” statement, which further triggered the public’s questioning of the platform’s data ethics and lack of supervision.

This digital violence has eventually evolved into a collective public interrogation of corporate ethics, platform mechanisms and family education. This incident not only demonstrates the real danger of doxxing, but also reveals how violence has infiltrated our daily social space in the guise of “justice” under the appearance of technological affirmative action.

Platforms Are Not Bystanders: How Algorithms Fuel the Fire

Retrieved from Pinterest.com

In this case, we see not just an individual’s behavior getting out of control, but a structural problem where, when violence is attractive enough, it tends to spread faster than justice.

In similar incidents, platforms are never bystanders, and platform algorithms are amplifying the violence. Matamoros-Fernández (2017) points out that Platformed racism is a product of the libertarian ideology, which is not a neutral system, but is full of incendiary, hateful content, a tool to create and amplify hate speech that is used to gain the attention of more users. Furthermore, Trottier (2017) calls this phenomenon “Weaponisation of Visibility”, where victims are not voluntarily seeking attention, yet personal privacy is exposed and disseminated on a large scale in a short period of time and persists on the internet, a kind of digital lynch mobbing, where it is very difficult for the victims to escape from the shadows of cyber-violence. In this incident, the private information of several victims was leaked, yet it managed to circulate wildly in the microblogging hotspots, and some of them even gained tens of thousands of likes and hundreds of retweets. It makes us not only question whether the platform has become an accomplice to cyber violence by acquiescing to such illegal acts of violence in order to gain more attention from users.

In addition, we question the platforms’ content review and regulatory mechanisms, as Caplan (2018) suggests that most mainstream platforms hide their content review policies, and that this opacity contributes to a ‘logic of opacity’ that makes platforms appear objective and neutral, but in reality is a means of avoiding public inquiry and scrutiny. At the end of this incident, Weibo deleted the relevant content and blocked the relevant accounts. But it can’t help but prompt us to ask why there is a perpetual lag in the platform’s regulation. Why is violence stopped only after it has harvested traffic? In this incident, the platform seems to be a passive bystander, but in fact, the platform’s algorithm has already chosen its position – ignoring justice and favoring traffic.

Behind Youth Violence: The Gaps in Culture, Education, and Law

In this incident, there is another point that deserves our attention. Why is a 13-year-old girl, without any technical background, able to dox others easily and boast of her “righteous deeds”? This does not come only from the girl herself, but is the result of society’s tolerance of online violence, the lack of education for young people and the inadequacy of the law.

First of all, the popularity of online community culture, such as fandom, has made cyberviolence commonplace, and in this environment, cyberviolence is entertained and rationalized. What is most disturbing is that teenagers are often the most active users of online communities, and at a stage when their values are not yet mature, they are more likely to be abetted and misled into committing cyberviolence against others. “Doxxing” is packaged as a righteous act of ‘standing up for idols’, which not only expresses their loyalty to their idol to gain peer approval, but also captures the traffic mechanism of the platform. But more seriously, the perpetrators are often also the victims, and when young people are subjected to cyberviolence, they often suffer even greater harm, with incalculable consequences.

In addition, digital literacy education for young people is seriously lagging behind, as they grow up on digital platforms, but many parents and schools fail to recognize the importance of a code of conduct for young people in the digital age, and fail to provide children with adequate education on cyberethics and privacy protection. So that many teenagers do not know how to draw boundaries and respect privacy, thus considering cyberviolence as a way to express their individuality, further blurring the line between violence and expression.

Nor can we ignore the regulatory loopholes in the existing laws. The existing legal system cannot effectively deal with cyber violence by minors. In this case, the 13-year-old girl was a minor and could not be held legally responsible. Although under Chinese law, the guardians of minors should bear certain responsibilities, in practice, the “cyber violence” behavior of minors is often ignored or indulged, leading to the spread of violence.

Retrieved from Pinterest.com

Conclusion

This “doxxing” incident allows us to unveil the veil of online violence, and see the real appearance of digital violence, which is not just a quarrel between netizens, nor is it simply the uncontrolled behavior of an individual – a child, but a multifaceted, structural problem, the traffic bias of platform algorithms, lagging platform regulation, social permissiveness, lack of digital literacy education, and loopholes in the current law all contribute to the problem.

In this “anyone may be seen, exposed, attacked” network era, we must not regard “doxxing” and other network violence as a helpless product of the Internet era, nor can we acquiesce in the platform and algorithm for traffic to damage our interests, but can not condone the occurrence of network violence. What we need is definitely not a superficial response such as “apology” and “block”, so we should put forward our demands, we need the platform to assume the responsibility of supervision and protection, we need the education system to cover the education of network literacy, and we need the deterrent and shelter of legal weapons.

Coping with this problem requires the joint efforts of many parties. But for all parties, this is a considerable challenge. For platforms, the usual thing is to establish a clear mechanism for content review and privacy protection, but in today’s world of free speech, how platforms can correctly balance the relationship between content review and free speech is a top priority. But even so, in the face of clear principles of right and wrong, such as the “doxxing” incident, platforms must fulfill their responsibility to censor and regulate content, so as to nip digital violence in the bud. Secondly, although commercial platforms aim to make profits, the bias of their algorithms must always be in the direction of justice. For the education system, there is still a long way to go for reform, and how to teach young people to respect the privacy and boundaries of others, as well as to have a sense of protecting their own privacy, is a goal that schools and families need to reach together. Although there is always a lag in the introduction of new laws, the law is always our strongest support. Whether it is China, Australia, or the whole world, there are more or less vacancies in the regulation of digital violence, how to define the new type of cyber-violence, and the boundaries of the responsibilities of minors and their guardians in the cyberspace are issues that need to be urgently resolved by the legal systems of various countries.

In this “best and worst” era of the Internet, what we need to build is not just a more technologically powerful platform, but a public digital space with boundaries, responsibilities and ethical boundaries. Because in the face of digital violence, silence is not neutrality, but complicity.

Reference

Eckert, S., & Metzger-Riftkin, J. (2020). Doxxing, privacy and gendered harassment: The shock and normalization of veillance cultures. Medien & Kommunikationswissenschaft, 68(3), 273–287. https://doi.org/10.5771/1615-634X-2020-3-273

Lee, C. (2022). Doxxing as discursive action in a social movement. Critical Discourse Studies, 19(3), 326–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2021.2016067

Anderson, B., & Wood, M. A. (2022). Harm imbrication and virtualised violence: Reconceptualising the harms of doxxing. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 11(1), 196–209. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.1991

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: The mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1293130

Trottier, D. (2017). Digital vigilantism as weaponisation of visibility. Philosophy & Technology, 30(1), 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-016-0216-4

Caplan, R. (2018). Content or context moderation? Data & Society. https://datasociety.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/DataAndSociety_Content_or_Context_Moderation.pdf

Be the first to comment