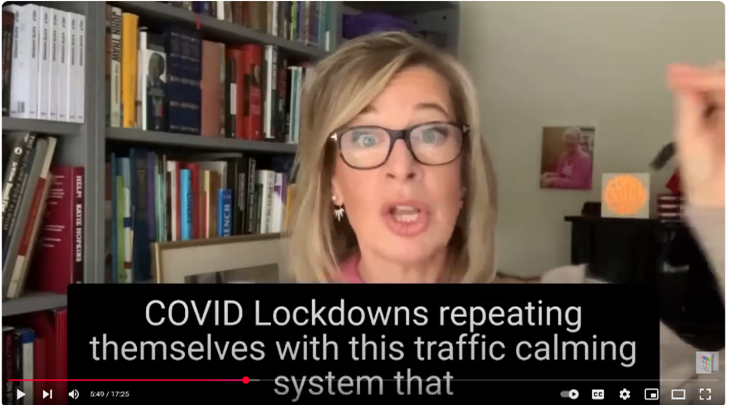

“Very soon, you will only have 15 minutes of freedom here in the UK”, Katie Hopkins warns her nearly 600,000 YouTube subscribers.

In Hopkins’ video, which has been viewed more than 123,000 times (and hundreds of thousands times more on TikTok and X), the far-right commentator claims that the recent traffic measures announced by Oxfordshire County Council are part of a sinister government plot.

Hopkins conflates the traffic measures with the ‘15-minute city’ urban planning concept, suggesting that people will only be allowed to drive 15 minutes from their homes – and this is all part of a bigger plan to enforce ‘climate lockdowns’. Before the video ends, Hopkins makes clear that “this isn’t a conspiracy theory” and she “absolutely anticipates this will have a warning on it, if it’s even left up”.

Well, Hopkins will be pleased to know that her video’s still up and YouTube hasn’t even flagged it for misinformation.

Conspiracy-19: the infodemic

The 15-minute city conspiracy is just one of the many conspiracy theories that circulated widely on social media following the outbreak of COVID-19. The global pandemic was accompanied by a similarly global ‘infodemic’ (Bruns et al., 2020), in which COVID-19 and lockdown-related conspiracy theories spread “faster and more easily than the virus” .

A sharp increase in rumours during times of uncertainty, such as a pandemic, is nothing new (Allport & Postman, 1946). But the speed and scale at which conspiracy theories now move ‘from fringe circulation to significant impact’ (Bruns et al., 2020) is unique to the last few decades (Mahl, et al., 2022).

Profound changes to the digital media landscape, particularly the proliferation of social media platforms, have enabled conspiracy theories to spread faster and further (Mahl, et al., 2022). So fast that fact-checking tools are often not quick nor accurate enough to slow the spread of conspiracy theories in their most viral stage (Chuai et al., 2024; Papakyriakopoulos et al., 2020).

This poses a challenge to current content moderation strategies, given that most platforms rely on fact-checking to counter the spread of conspiracy theories on their sites – whether by a third-party, automated tools, a combination – like YouTube’s fact-checking programmes and TikTok’s Global Fact-checking Program –, or crowdsourced – like the Community Notes feature on X and, as of recently, also on Meta.

So, to better combat the spread of conspiracy theories online, do platforms need to consider countermeasures beyond fact-checking and community notes? What role do bots, influencers and algorithms play in pushing conspiracy theories online?

What is a conspiracy theory?

Conspiracy theories can be defined as attempts to explain significant events and circumstances as the secret and malicious acts of powerful groups (Douglas et al., 2021; Schatto-Eckrodt et al., 2024). This idea of perceived injustices by ‘powerful groups’ helps explain why populist leaders and their supporters spread conspiracy theories more often than other politicians and party supporters (Butter, 2024).

What differentiates conspiracy theories from related terms, like ‘misinformation’ (nonintentional deception) and ‘disinformation’ (intentional deception), is that conspiracy theories provide ‘alternative explanations’. This means that they are often, but not necessarily always, wrong (Mahl et al., 2023; Schatto-Eckrodt et al., 2024; Uscinski, 2018). This underscores the challenge that content moderators face in drawing the line between “healthy scepticism” and “unhealthy conspiracy theorising” (Schatto-Eckrodt et al., 2024).

Another related term, ‘fake news’, is relatively unhelpful in the context of conspiracy theories. Lazer et al. defines fake news as ‘fabricated information that mimics news media content in form but not in organizational process or intent … fake-news outlets … lack the news media’s editorial norms and processes for ensuring the accuracy and credibility of information’ (2018). While conspiracy theories may fall within this category, fake news is broader.

The term ‘fake news’ has also become a ‘floating signifier’ in the last decade, after being weaponised by the President of the United States, Donald Trump, during the 2016 election campaign(Farkas & Schou, 2018). Trump has co-opted the term as “a blanket retort” (Bennett, Livingston, 2020) to “news outlets that publish stories critical of them” (Flew, 2021), leading the term far astray from its actual meaning.

Harmless fun or something more sinister?

For a long time, conspiracy theories were seen as harmless phenomena that only operated in “socio-cultural niches” (Mahl et al., 2022; Asprem & Dyrendal, 2018). Claims that ‘the moon landing was a hoax’ or that ‘Paul McCartney died 59 years ago and a doppelganger’s been taking his place ever since’ seemed funnier than threatening.

This has changed in recent decades, however. With the advent of social media platforms, known for their easy accessibility, algorithms and networking opportunities, conspiracy theories that may have previously been seen as “silly and without merit” (Keeley, 2006) have entered the mainstream (Mahl et al., 2022).

We have seen a wave of “high-profile conspiracy theorising” (Uscinski, 2018) with real-world impacts: from the COVID-19 response, to the Capitol riot – linked to the 2020 US presidential election conspiracy theory –, to several violent acts linked to the QAnon far-right conspiracy.

Beyond these individual cases, research has found that conspiracy theories are associated with prejudice, crime, violence, poor workplace behaviour, mistrust in science, and illegitimate political engagement (Douglas et al., 2021).

Ultimately, conspiracy theories today pose a real threat to social cohesion and national security, and they can no longer be shrugged off as harmless.

Influencers, algorithms and entrepreneurs: the new era of conspiracism

On the early Internet, the avenues available for spreading conspiracy theories were costly, slow and often traceable (Karpf, 2021). Consider chain emails: it requires far more effort to forward an email to 200 friends than it does to “like” or share a post with all your followers who are then algorithmically exposed to it (Karpf, 2021).

Social media has provided a new arena for conspiracy theorists, enabling them to bypass traditional gatekeepers and enter popular culture and political discourse (Mahl et al., 2022; Zeng et al., 2022). In a 2020 study, 83% of stories promoting COVID-19 conspiracy theories originated from social media, personal blogs and fake news sites (Papakyriakopoulos et al., 2020).

Social media platforms offer conspirators:

Fake accounts and bots to spread automated messages to targeted groups and get topics trending. Bots accounted for 20% of the conversations about politics in the weeks before the 2016 US presidential election (Snyder, 2018).

Algorithms that prioritise content with high engagement, meaning negative content that triggers an emotional response spreads more rapidly and persistently (Kwon and Gruzd, 2017; Pröllochs et al., 2021).

Influencers and ‘conspiracy entrepreneurs’ (Rosenblum & Muirhead, 2020). A 2025 study found that influencers significantly impacted the spread and persuasiveness of COVID conspiracy theories on X, particularly in the initial stages of spread (Meng et al., 2025).

A character limit, which encourages conciseness rather than explanation and evidence.

Visible likes and shares, which provide a new kind of legitimacy to conspiratorial claims (Rosenblum & Muirhead, 2020).

Urban myth: 15-minute cities

Before the ‘15-minute city’ idea was hijacked by conspiracists, it was introduced by Professor Carlos Moreno in 2016 as an urban planning concept (Moreno et al., 2021). Moreno proposes that everyday destinations, like schools, parks and shops, should be within a 15-minute radius by foot or bike of where people live. The idea is that this creates more self-sufficient, sustainable, and less car-dependent neighbourhoods (Moreno et al., 2021). There is no requirement to stay in your neighbourhood, but it incentivises ‘local living’ (Waite, 2023).

During the pandemic, the 15-minute city attracted the attention of politicians, with Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo making the idea a key part of her successful 2020 re-election campaign. The concept has also been introduced in Melbourne, Copenhagen, Edmonton, and Utrecht (City of Edmonton, 2022; Waite, 2023).

Then, the 15-minute city took a weird turn.

After the British county of Oxfordshire announced a traffic filter scheme to reduce congestion, claims began to circulate online that the scheme was a plot to imprison people within strict “15-minute” boundaries. A key instigator in the initial spread of the conspiracy was far-right commentator Katie Hopkins, who expressed her anger and anxiety in a YouTube video – despite the theory being fact-checked as false by AP News days earlier. Negative content, like Hopkins’, is effective in triggering an emotional response and interactions (Kwon and Gruzd, 2017; Pröllochs et al., 2021), which is rewarded by social media algorithms.

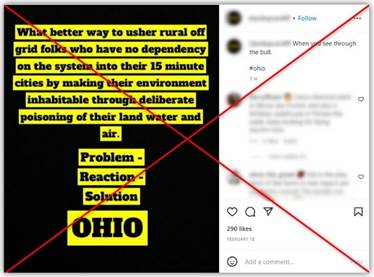

Hopkins and the conspiracists drew links to existing COVID-related myths, like ‘climate lockdowns’ and ‘The Great Reset’. Cross-topic connections like these on social media platforms can create networked ‘coalitions’ between online conspiracy theory communities (Mahl et al., 2021). This also demonstrates the ‘ready-to-build’ nature (Schatto-Echrodt et al., 2024) of today’s conspiracy theories, which, coupled with the speed of social media, mean conspiracy theories are ready for rapid dissemination online following significant events.

A pivotal point in the spread of the 15-minute city conspiracy came on 1 January 2023, when renowned Canadian celebrity psychologist, Jordan Peterson, tweeted about the ‘well-documented plan’ to his 6 million followers:

The idea that neighborhoods should be walkable is lovely. The idea that idiot tyrannical bureaucrats can decide by fiat where you're "allowed" to drive is perhaps the worst imaginable perversion of that idea–and, make no mistake, it's part of a well-documented plan. https://t.co/QRrjVF615q

— Dr Jordan B Peterson (@jordanbpeterson) December 31, 2022

Peterson’s tweet, viewed 7.6 million times, follows the trend of building on existing conspiracy myths, linking to the “Great Reset,” which conspiracists argue is a pandemic-fuelled plot by the World Economic Forum to destroy capitalism.

Neither Hopkins’ nor Peterson’s posts appear to have been fact checked on X or YouTube, bringing into question the accuracy and effectiveness of these platforms’ misinformation detection and response processes.

While Reuters and RMIT published fact-checking articles a few days after Hopkins posted her video, it appears this was not fast or effective enough to significantly combat the influence of well-known online figures like Hopkins and Peterson, with the conspiracy continuing to spread globally. As Keeley argues, conspiracy theorists often assume the real facts are unpublished secrets (2006), so official statements and fact-checking is unlikely to sway their beliefs.

This frustration of not being able to use facts to calm the viral claims of social media conspiracists is felt by Moreno:

“I was not totally sure what is the best reaction — to respond, to not respond, to call a press conference, to write a press release… It is totally unbelievable that we could receive a death threat just for working as scientists” (in The New York Times, 2023).

So, does fact-checking work to combat conspiracy theories?

Well, sometimes – if it’s quick enough.

A 2021 study of tweets related to the “5GCoronavirus” conspiracy theory found that fact-checking is useful in the early stages of conspiracy theory spread but fails in later stages. Tweet deletion is less useful, but also less time-dependent than fact-checking (Kauk & Schweinberger, 2021).

The ineffectiveness of fact-checking at later stages of spread may suggest that to be effective, fact-checking needs to take place well before memory consolidation of conspiracy theories has occurred (Kauk et al, 2021).

And this is hard to accomplish on social media, where messages duplicate and circulate so quickly.

Both human and automated detection algorithms struggle to keep up with the volume and speed of information being spread (Lee et al., 2019). A 2020 study of COVID conspiracy theories on Reddit, Twitter and Meta found that the platforms fact-checked less than half the posts with conspiracy theory messages, and fact-checking often occurred several weeks after the posts went viral (Papakyriakopoulos et al., 2020). Additionally, the effectiveness of automated fact-checkers is constrained by their potential for bias (Wu et al, 2019) and inability to detect new kinds of content, such as deep fakes (Rana et al., 2022).

Crowdsourced efforts are no more effective, with a recent study of the Community Notes feature on X finding that it is too slow to reduce engagement with misinformation in the initial, most viral stage of spread (Chuai et al., 2024).

Overall, this is not to suggest that fact-checking should be foregone entirely. Fact-checking is a critical tool in the fight against misinformation (Porter & Wood, 2021).

But, in the context of conspiracy theories, reliance on fact-checking alone is not enough to curb the rapid and persistent spread of harmful conspiracies (Artime et al., 2020).

Big Tech, bigger responsibility

Ultimately, if platforms are serious about building trustworthy community spaces on their sites, they need to bolster their fact-checking efforts. This could include:

- Tailored measures for different stages of spread (Meng et al., 2025), such as:

- better management of influencers and conspiratorial entrepreneurs in the early stages of spread

- targeting and removal of bots in later stages of spread

- Combined fact-checking processes (Pilarski et al., 2024)

- Partnerships with researchers (Gorwa et al., 2020; Susarla, 2025)

- Platform-supported auditing of algorithms for public interest (Iman et al., 2023)

It shouldn’t take the occurrence of horrific events, like the Capitol riots, for platforms to finally take serious action against the spreaders of conspiracy theories.

In the current digital and geopolitical environment, conspiracies are no longer harmless tales – they are threats to the fabric of society.

——————————————————————————————————————–

References

Allport, GW., and Postman, L. (1946). An analysis of rumor. Public Opinion Quarterly 10(4): 501–517.

Artime, O., d’Andrea, V., Gallotti, R., Sacco, P. L., & De Domenico, M. (2020). Effectiveness of dismantling strategies on moderated vs. unmoderated online social platforms. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 14392–14392. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71231-3

Asprem, E., & Dyrendal, A. (2018). Close Companions? Esotericism and Conspiracy Theories. In Handbook of Conspiracy Theory and Contemporary Religion (Vol. 17, pp. 207–233). https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004382022_011

Bennett, Livingston, Livingston, S., & Lance Bennett, W. (2020). The Disinformation Age (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108914628

Bruns, A., Harrington, S., & Hurcombe, E. (2020). ‘Corona? 5G? or both?’: the dynamics of COVID-19/5G conspiracy theories on Facebook. Media International Australia, 177(1), 12-29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X20946113

Butter, M. (2024, August 27). Populism and Conspiracy Theory. Australian Institute of International Affairs. https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/populism-and-conspiracy-theory/

Chuai, Y., Tian, H., Pröllochs, N., & Lenzini, G. (2024). Did the Roll-Out of Community Notes Reduce Engagement With Misinformation on X/Twitter? Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 8(CSCW2), 1–52. https://doi.org/10.1145/3686967

City of Edmonton (2022). Fostering 15-Minute Communities. https://www.edmonton.ca/sites/default/files/public-files/ZBRI_ConvStarter-03-Fostering15min.pdf

Douglas, K. M. (2021). Are Conspiracy Theories Harmless? The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 24, e13. doi:10.1017/SJP.2021.10

Farkas, J., & Schou, J. (2018). Fake News as a Floating Signifier: Hegemony, Antagonism and the Politics of Falsehood. Javnost – The Public, 25(3), 298–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2018.1463047

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. Polity Press.

Gorwa, R., Binns, R., & Katzenbach, C. (2020). Algorithmic content moderation: Technical and political challenges in the automation of platform governance. Big Data & Society, 7(1), 205395171989794-. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951719897945

Hsu, T. (2023, April 8). He wanted to unclog cities. now He’s ‘Public enemy no. 1’. New York Times. https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/he-wanted-unclog-cities-now-s-public-enemy-no-1/docview/2797694998/se-2

Imana, B., Korolova, A., & Heidemann, J. (2023). Having your Privacy Cake and Eating it Too: Platform-supported Auditing of Social Media Algorithms for Public Interest. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 7(CSCW1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1145/3579610

Karpf, D. (2020). How Digital Disinformation Turned Dangerous. In Bennett, W. L., & Livingston, S. (Eds.). The Policy Problem. In The Disinformation Age (pp. 151–210). part, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108914628

Kauk, J., Kreysa, H., & Schweinberger, S. R. (2021). Understanding and countering the spread of conspiracy theories in social networks: Evidence from epidemiological models of Twitter data. PloS One, 16(8), e0256179–e0256179. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256179

Keeley, B. (2006). Of conspiracy theories. In D. Coady (Ed.), Conspiracy theories: The philosophical debate, 45–60. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315259574

Kwon, K. H., & Gruzd, A. (2017). Is offensive commenting contagious online? Examining public vs interpersonal swearing in response to Donald Trump’s YouTube campaign videos. Internet Research, 27(4), 991–1010. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-02-2017-0072

Lee, S., Xiong, A., Seo, H., & Lee, D. (2023). “Fact-checking” fact checkers: A data-driven approach. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review. https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-126

Mahl, D., Schäfer, M. S., & Zeng, J. (2022). Conspiracy theories in online environments: An interdisciplinary literature review and agenda for future research. New Media & Society, 25(7), 1781-1801. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221075759

Meng, X., Wang, X. and Zhao, X. (2025), “The dynamics of conspiracy theories on social media from the diffusion of innovations perspective: the moderating role of time”, Internet Research, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-07-2024-1123

Moreno, C., Allam, Z., Chabaud, D., Gall, C., & Pratlong, F. (2021). Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, resilience and place identity in future post-pandemic cities. Smart Cities, 4(1), 93–111. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities4010006

Papakyriakopoulos, O., Medina Serrano, J. C., & Hegelich, S. (2020). The spread of COVID-19 conspiracy theories on social media and the effect of content moderation. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review. https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-034

Pilarski, M., Solovev, K. O., & Pröllochs, N. (2024). Community Notes vs. Snoping: How the Crowd Selects Fact-Checking Targets on Social Media. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 18(1), 1262-1275. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v18i1.31387

Porter, E., & Wood, T. J. (2021). The global effectiveness of fact-checking: Evidence from simultaneous experiments in Argentina, Nigeria, South Africa, and the United Kingdom. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences – PNAS, 118(37), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2104235118

Pröllochs, N., Bär, D., & Feuerriegel, S. (2021). Emotions in online rumor diffusion. EPJ Data Science, 10(1), 51–17. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjds/s13688-021-00307-5

Rana, M. S., Nobi, M. N., Murali, B., & Sung, A. H. (2022). Deepfake detection: A systematic literature review. IEEE Access, 10, 25494–25513. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3154404

Rosenblum, N. L., & Muirhead, R. (2020). A Lot of People Are Saying : The New Conspiracism and the Assault on Democracy. Princeton University Press,. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691204758

Schatto-Eckrodt, T., Clever, L., & Frischlich, L. (2024). The Seed of Doubt: Examining the Role of Alternative Social and News Media for the Birth of a Conspiracy Theory. Social Science Computer Review, 42(5), 1160-1180. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944393241246281

Susarla, A. (2025, January 16). ‘Meta shift from fact-checking to crowdsourcing spotlights competing approaches in fight against misinformation and hate speech’. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/meta-shift-from-fact-checking-to-crowdsourcing-spotlights-competing-approaches-in-fight-against-misinformation-and-hate-speech-246854

Uscinski, J. E. “The study of conspiracy theories.” Argumenta 3.2 (2018): 233-245. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=The+study+of+conspiracy+theories&author=JE+Uscinski&publication_year=2018&journal=Argumenta&pages=233-245

Waite, T. (2023, January 3). The 15-minute city: dystopian conspiracy, or climate-friendly paradise?. Dazed. https://www.dazeddigital.com/life-culture/article/57869/1/15-minute-city-dystopian-right-wing-conspiracy-climate-friendly-paradise-tiktok

Wu, L., Morstatter, F., Carley, K. M., & Liu, H. (2019). Misinformation in social media. ACM SIGKDD Explorations Newsletter, 21(2), 80–90. https://doi.org/10.1145/3373464.3373475

Zeng, J., Schäfer, M. S., & Oliveira, T. M. (2022). Conspiracy theories in digital environments: Moving the research field forward. Convergence, 28(4), 929-939. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565221117474

——————————————————————————————————————–

Disclaimer: ChatGPT was used to generate the first image in this article. ChatGPT, nor any other AI tool, was used for the research and writing of this article.

Please note: I had some trouble with the WordPress formatting of image captions and dot points. This will be rectified in the document version I submit on Canvas. Thank you!

Be the first to comment