Figure 1 An illustration of cyberbullying and digital justice-hate speech targeting an individual through social media. Image via Unsplash.

Background

In the digital media era, social platforms increasingly dominate public opinion, and individual moral judgments and group emotions are often rapidly expanded through “justice”. When network users mobilize public opinion with the starting point of “voicing”, “exposing” and “protecting rights”, the originally well-intentioned behaviors often evolves into highly emotional verbal attacks, and even escalate to extreme behaviors such as “human flesh search” and “cyber blasts”. This phenomenon is different from traditional hate speech and is a more complex form of expression: this kind of behavior starts from justice but implies strong attacks on individuals and harm to society. This article will focus on the phenomenon of justice-driven hate speech on social media, explore its generation mechanism, diffusion logic and potential harm on social media, and point out the impact and challenges of this phenomenon on digital policies and governance.

Introduction of some key concepts

In order to deeply understand the rise and spread of “justice-driven hate” on social platforms, this article will build an analytical framework from three dimensions of the communication characteristics of digital public space, platform-driven mechanisms, and participatory shaming culture on the Internet. Understanding key concepts can explain the complexity of this phenomenon and provide a basis for subsequent critical analysis and governance discussions sections.

The “online public space” proposed by Danah Boyd (2014) emphasizes that social media platforms are not just channels for information transmission, but also build a new type of public social sphere with high visibility, easy dissemination, and low threshold participation. In this space, individual behaviors are amplified, especially content with strong emotional colors and positions, which arouses users’ resonance and group response. At the same time, the economic attributes of the platform itself also subtly promote the extremism of emotional expression. Zuboff (2019) suggests in his theory of “surveillance capitalism” that due to its economic attributes, social platform algorithms tend to push content that can stimulate emotions to capture users’ attention and justice-driven hate speech can be rapidly spread and gradually become biased by algorithmic drive. The algorithms of social platforms tend to push content that can stimulate emotions to capture users’ attention, and justice-driven hate speech driven by algorithms can proliferate quickly and gradually deviate from rational discussion. In addition, the “participatory shaming” theory proposed by Marwick and Boyd (2011) can reasonably explain that users can strengthen their moral identity by participating in the public shaming of others, and this kind of hate speech is not based on facts but relies on emotional amplification and labeling to quickly complete the position division, and ultimately forms a collective siege in the network, causing harm to individuals. Therefore, righteous hate speech is the result of the interaction between social platform mechanisms, users’ emotions and network culture.

Why does a “sense of justice” so easily turn into an attrack?

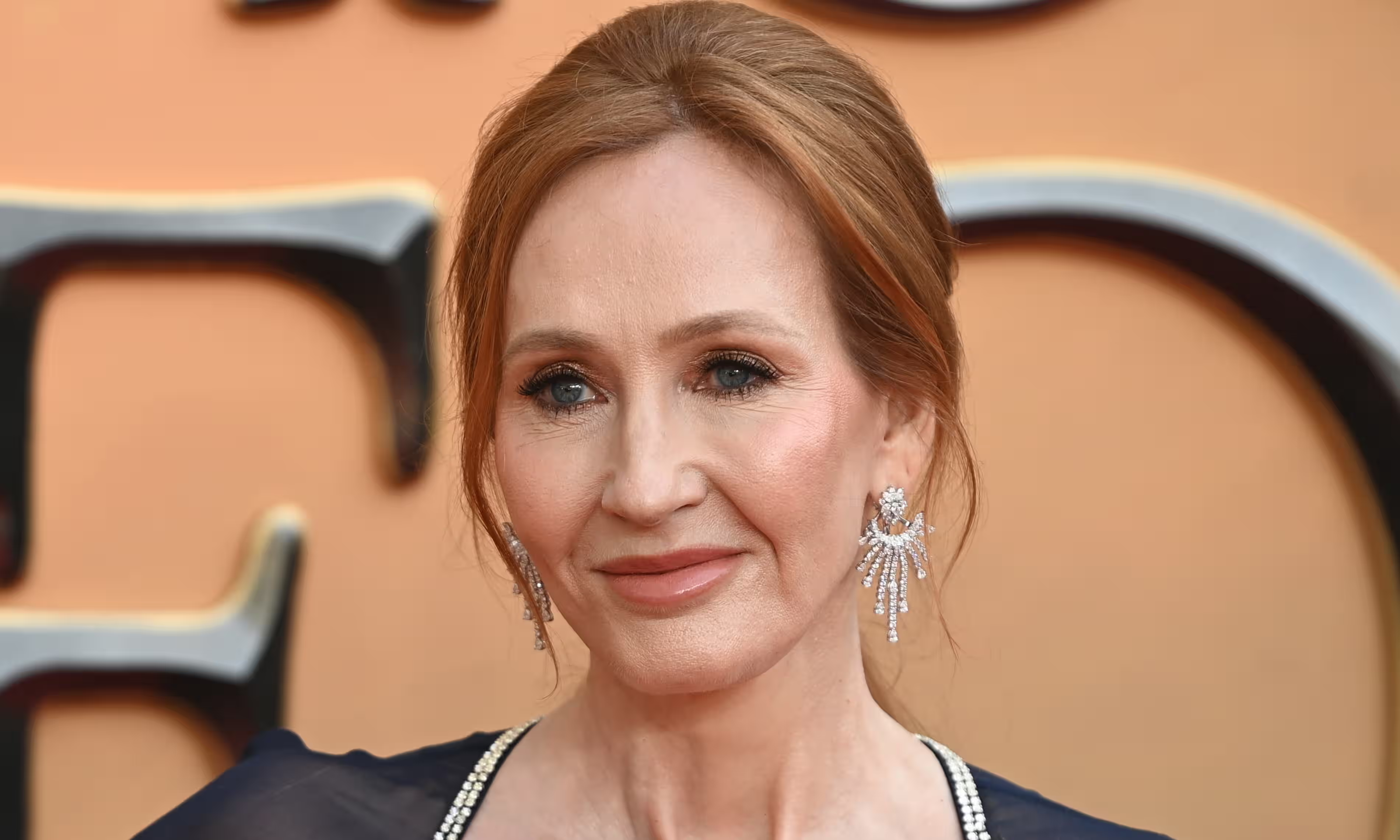

In 2020, writer JK Rowing was labeled “TERF” because she advocated the protection of “biological female rights” on Twitter, which triggered strong attacks from some transgender groups. The comments section of the social media has long been filled with insults, and users have initiated insults, boycotts, blocking and other offensive behaviors in the name of “defending transgender rights”, which has evolved into “justice-driven hate speech”. The offensive behavior of this group on social platforms is a collective expression of “moral justice”. They are not simply “insulting”, but participating in a “boundary division” and treating JK Rowing as an enemy. This process clearly shows how “justice” in the highly emotional public environment of social platforms has evolved into a humiliating and exclusionary form of attack in a short period of time.

Figure 2 JK Rowling Image via The Guardian

What is the booster of emotions?

Based on the above examples, it can be seen that content that can cause emotional fluctuations often spreads faster than rational content on social media platforms. A statement full of anger and accusation and with a certain value judgment can often trigger hundreds of comments and retweets, which in turn drives the algorithm to make it seen by more users with the same values. As Gillespie (2018) pointed out, social platforms are not neutral speech spaces. They use a series of algorithms, recommendation mechanisms and sorting logic to invisibly determine which voices are seen and which are ignored. In the case of emotionally or morally charged speech, such mechanisms provide an institutional incentive for the proliferation of “justice-driven hate” speech. A typical example is the case of Paris Tier, an Australian TikTok user and partner of an AFL player, who shared a video of herself dancing and confidently expressing body positivity, the comment area was quickly divided into two camps: “aesthetic freedom” and “moral criticism”. Due to its heated debate and high emotional concentration, the video was continuously pushed by the algorithm, which eventually triggered large-scale onlookers and secondary attacks. Therefore, the algorithm does not care about justice or not, but promotes the expression of emotions. When Internet users accept the algorithmic logic that “positive correlation between the heat of the comments and the degree of justice”, the platform acquiesces to emotional mobilization as a way to dominate public opinion.

Figure 3 TikTok creator Paris Tier responds to past body-shaming attacks by sharing her story through ABC News and social media. Image via Tiktok

When “justice” becomes a siege, who will be hurt?

When “justice” turns into hatred, it ultimately hurts innocent individuals and erodes the environment of the platform space for public discussion. The besieged are often attacked simply because their positions are not “pure” enough or their words are not “correct” enough. They will face long-term psychological pressure, leading to anxiety and depression, and may even delete their accounts and quit the Internet. Although JK Rowling stood firm in the subsequent period, she was harassed and boycotted for a long time. This confirms what Ronson (2015) called “cyber-execution”, online shaming behavior is often presented as “deserved punishment,” but in fact it carries a psychological burden far beyond that of offline conflict. Hate speech not only expresses hostility, but also causes “constitutive harm” and “causal harm” by denying the rights of others to exist, to express themselves, and to autonomy, i.e., by humiliating and demeaning the individual under siege, as well as causing actual discrimination, violence, or social exclusion or social exclusion (Sinpeng, 2021). This phenomenon is also changing the behavior of some users. For example, the phenomenon of “being hung up as soon as you speak out” has appeared on the rednote platform. Some users who publish neutral content have also been accused of “standing on the wrong side” and can only delete their comments to prevent risks. When people begin to be afraid to express themselves and actively avoid them, individuals lose the freedom of expression and safety boundaries they should have, and the digital public space also loses its original diversity and discussion.

Can platform regulation be enforced “justly”?

Platforms are often able to quickly identify traditional hate speech. Flew (2021) pointed out that platforms tend to be more content neutral, while “justice-driven hate speech” wanders between value expression and moral attack. Platforms are worried that intervention will be questioned as “suppressing freedom of speech”, which puts platform regulators in a dilemma when governing. Even more problematic is the fact that the current legal framework has not been updated in time to respond to such changes in social platforms. For example, the Online Safety Act 2021 introduced by Australia mainly targets serious bullying and violent content on the Internet, but there is no clear definition and intervention method for this kind of discourse attack based on the moral level. In such a gray area, platforms can pass the buck and users cannot seek protection from the system.

Roberts (2019) emphasizes that most platforms treat their content review process as a corporate secret, and do not disclose their review criteria to avoid users from “exploiting” or triggering public criticism. In the context of the increasing complexity of the fuzziness and disguise of hate speech, the platform’s opaque strategy has instead contributed to the survival and spread of harmful content. Instead of simply deleting or blocking posts, we should establish more detailed language identification mechanisms and more sensitive early warning and judgment capabilities, relying on culturally sensitive human judgment, while shifting the direction of regulation from “motivation for expression” to “consequences of harm”. Meanwhile, the direction of regulation should also shift from “motivation for expression” to “consequences of harm”.

What should be done? Rethinking governance in the age of justice-driven hate

Even if “justice-driven” speech is not driven by malice, it has caused real harm. Currently in the governance has not been synchronized update, we first need to think about how to build a more resilient expression mechanism and governance logic, rather than technical direct “delete posts”. For the platform, the current recommendation algorithm prioritizes highly controversial and highly engaged content, and tacitly allows extreme justice speech to become mainstream. The platform may need to introduce a “cooling mechanism” and “emotion recognition system” in the future governance mechanism, and control the platform’s rational communication space by delaying review and restricting recommendations before the speech spreads uncontrollably. In terms of policy, the law should not be limited to traditional “hate speech” or “illegal content,” but should be sensitive to “moral offense” in all contexts of social platforms. The Online Safety Act mentioned above could be expanded to accommodate t varying degrees of “non-malicious but highly injurious” ambiguous moral offense speech. In addition, regulators need to work with platforms to develop systems for identifying content in different contexts. For users, when facing controversy, we need to think about the truth and impact behind the incident, slow down the forwarding speed, and delay the transmission of emotions. In today’s social environment, we need to realize that it can be a split second between “taking sides” and “mobbing”. We may not be able to stop all the outbreaks of “justice-driven hate” speech, but each individual’s calm expression is a guardian of rationality and equality in cyberspace.

Conclusion

On social platforms where information circulates at high speed and emotions are easily expressed, “justice-driven hate” deserves more attention because of its concealment. It occurs in the name of maintaining social values, but under the influence of emotional appeals and platform mechanisms, it harms individuals and pollutes the social space. As we can see in the previous section, this phenomenon is generated by moral demarcation and group identity, and then further spreads with the help of algorithms, and finally brings different degrees of harm. For platforms, this is a blind spot in governance; for the laws governing digital space, this is a challenge brought about by the evolving language of regulation. The phenomenon of “justice hate” also reminds us that before we quickly speak out and take sides, we should determine whether we are fighting for justice or furthering digital violence.

Reference

Deogracias, A. (2014). Danah Boyd: It’s complicated: The social lives of networked Teens. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(5), 1171–1174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0223-7

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. John Wiley & Sons.

Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the Internet: platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL26961115M/Custodians_of_the_internet

Marwick, A., & Boyd, D. (2017). The Drama! Teen Conflict, Gossip, and Bullying in Networked Publics. A Decade in Internet Time: Symposium on the Dynamics of the Internet and Society. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/aknux

Roberts, S. T. (2019). 2. Understanding commercial content moderation. In Yale University Press eBooks (pp. 33–72). https://doi.org/10.12987/9780300245318-003

Ronson, J. (2015). So you’ve been publicly shamed. Pica https://williamwolff.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/ronson-2015.pdf

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F. R., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021). Facebook: Regulating Hate Speech in the Asia Pacific. Department of Media and Communications, the University of Sydney, and the School of Political Science and International Studies, the University of Queensland. https://doi.org/10.25910/j09v-sq57

Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. https://cds.cern.ch/record/2655106

Be the first to comment