A Crisis of Trust and the Rise of Pandemic Lies

“They’re killing people,” President Biden said loudly enough to be heard under the roar of his Marine One helicopter idling on the South Lawn of the White House on a Friday in July 2021. He was not referring to terrorists or arms dealers, but to Silicon Valley tech moguls—most notably Mark Zuckerberg and Sheryl Sandberg—whose company Facebook was under fire for enabling the spread of dangerous misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines. “The only pandemic we have is among the unvaccinated,” he continued. “And they’re killing people.”

Biden’s statement captured the growing frustration among public health leaders and policymakers over the role of social media platforms in accelerating the spread of disinformation. As infections surged in vaccine-hesitant communities, it became clear that false narratives were thriving—despite efforts to remove or flag misleading posts. At the heart of this issue is a much deeper crisis: a decline in public trust toward mainstream institutions, including government and media, and a corresponding rise in emotionally resonant but false information filling the void.

This blog argues that the rapid spread of disinformation and fake news during the COVID-19 pandemic cannot be understood without acknowledging the broader social and emotional context. In an era where public trust in mainstream media and government institutions is steadily eroding, people increasingly seek alternative sources of information—especially those that offer emotional comfort and a sense of belonging. Disinformation campaigns, such as Plandemic, skillfully exploited this emotional vacuum. They were propelled not by large-scale popular movements, but by a small number of influential ‘superspreaders’ who manipulated platform algorithms and user sentiment. The failure of major platforms like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter to respond quickly and effectively to disinformation only worsened the problem, allowing misleading narratives to flourish during a moment of global vulnerability.

A Brief History of Distrust: From Neoliberalism to Pizzagate

Although “fake news” has become a buzzword in recent years, the concept is nothing new. As Terry Flew (2021) notes, scholars now prefer terms like “misinformation” (false information shared without intent to harm) and “disinformation” (deliberately false content designed to mislead). The latter is more insidious, often created and spread with political motives.

But how did such manipulative content gain such fertile ground? One major factor lies in the historical shift driven by neoliberal ideologies, which reframed public discourse by emphasizing market values over civic ones and gradually eroded democratic institutions. Bennett and Livingston (2020) argue that although neoliberalism successfully sold market liberalization policies to voters in the 1980s and 1990s—such as deregulation and privatization—over time, the promised prosperity and freedom failed to materialize for many. Gradually, people began to see that the “freedom” promised by neoliberal policies mostly meant giving more power to markets and businesses—not more rights or democratic control for ordinary people.

This growing sense of disillusionment did not merely produce political apathy—it created a vacuum of trust. As promises of prosperity failed to reach many, citizens began to look elsewhere for explanations and meaning. Into this vacuum stepped disinformation: simple, emotionally charged narratives that offered clarity in place of complexity, and community in place of alienation.

Pizzagate, one of the earliest viral conspiracy theories of the digital age, is a telling example of how this environment of distrust allowed fringe beliefs to gain traction. This conspiracy theory first emerged in 2016 on fringe platforms like 4chan and Reddit—particularly in subreddits like r/The_Donald and r/Pizzagate. From there, it spread widely through YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter. It falsely claimed that Hillary Clinton and other Democratic Party elites were running a child trafficking ring out of a pizza restaurant in Washington, D.C. This conspiracy eventually drove a man to enter the restaurant armed with a rifle. Fortunately, no one was harmed, but the event highlighted the real-world danger of online disinformation.

Pizzagate set the stage for a new type of media manipulation: emotionally charged, easily shareable, and deeply distrustful of institutions. It demonstrated how fringe beliefs could penetrate mainstream discourse, especially when wrapped in compelling, emotionally resonant stories.

Plandemic and the Psychology of Disinformation

Plandemic: Faster Than the Virus

The emotional dynamics laid bare by Pizzagate foreshadowed what would unfold on an even larger scale during the COVID-19 pandemic. As fear, confusion, and isolation swept across the globe, the conditions were ripe for another wave of emotionally manipulative content to take hold—this time with higher stakes and broader consequences.

On May 4, 2020, a 26-minute video titled Plandemic was released online. Produced by anti-vaccine activists, it claimed that the coronavirus was engineered, face masks were dangerous, and the vaccine campaign was a global control plot. It politicized public health by targeting officials like Dr. Anthony Fauci and linking the pandemic response to a shadowy elite, including Bill Gates.

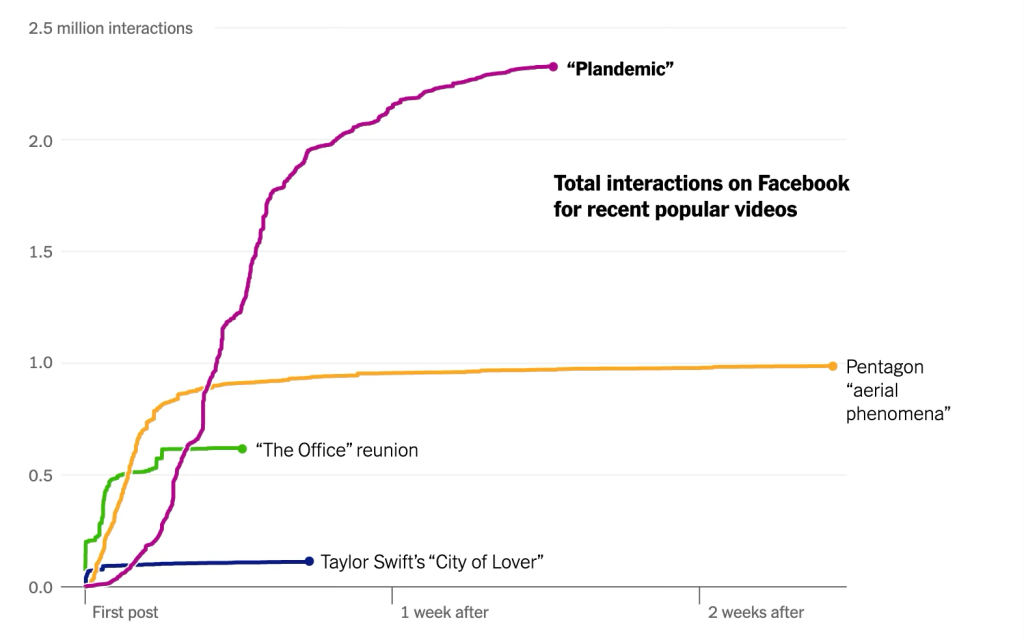

Just a little more than a week after its release, “Plandemic” had already attracted over eight million views across platforms like YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, sparking a flood of related posts. According to data from CrowdTangle, a tool that tracks activity on social media, “Plandemic” received nearly 2.5 million likes, comments, or shares on Facebook — significantly surpassing the roughly 110,000 interactions generated by Ms. Swift’s May 8 announcement of her “City of Lover” concert.

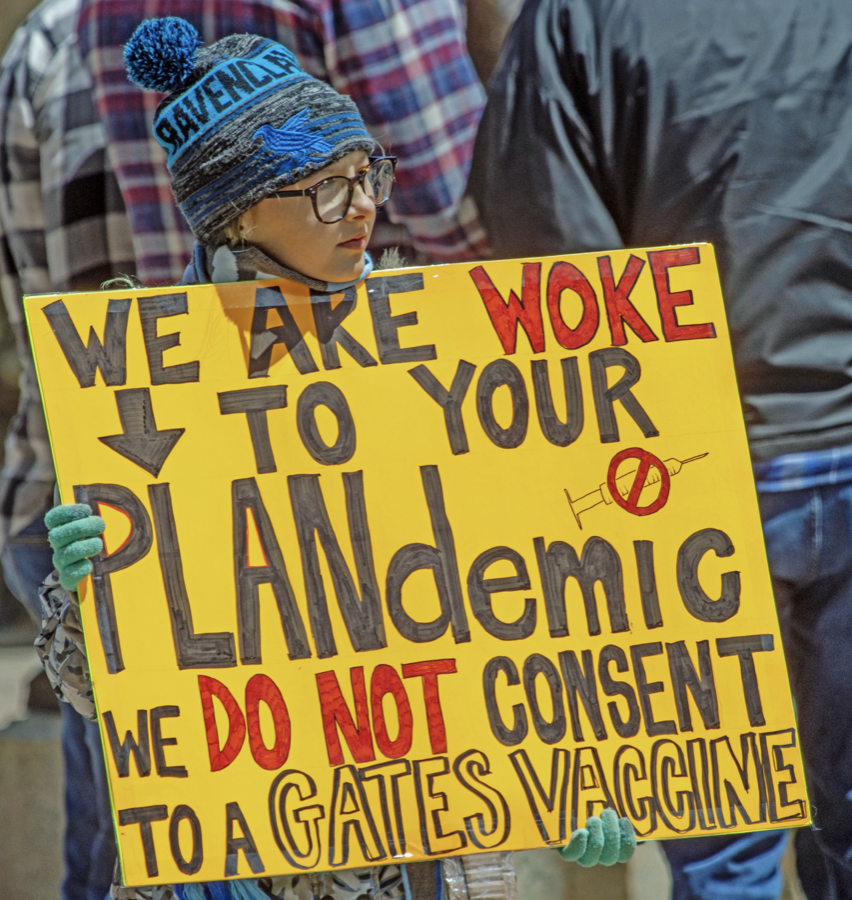

The conspiracy theories it promoted sowed seeds of doubt in the public mind, leading many to question public health guidelines, resist wearing masks, and refuse vaccination. In some countries, these messages even fueled anti-lockdown and anti-vaccine protests.

Photo by Becker1999, via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0).

Why It Felt So Right to Be So Wrong: The Viral Power of Feeling “Awake”

Kearney, Chiang, and Massey (2020) explain that Plandemic successfully hijacked public emotion by capitalizing on uncertainty, fear, and a growing sense of alienation. The video framed its narrative as a grassroots movement, urging viewers to “do your own research” and “seek the truth.” These emotionally charged appeals played into a deeper psychological tendency: people are more likely to believe information that aligns with their fears or confirms existing suspicions, even if it’s factually unsound (Bennett & Livingston, 2020).

In other words, Plandemic offered something powerful: a sense of control. It replaced scientific ambiguity with moral clarity. Instead of feeling like helpless victims of a complex virus, viewers were invited to become awakened truth-seekers. This shift from passive recipient to active investigator was deeply empowering—and that emotional empowerment helped the video go viral.

Furthermore, this disinformation strategy also tapped into themes of identity and belonging. Within anti-vaccine communities, the term “truth” frequently appears in user bios and hashtags (Shahin and Pieters, 2021). Users form digital tribes around shared narratives of resistance, often positioning themselves as protectors of family, liberty, or national values. This sense of mission strengthens their commitment and shields them from opposing facts.

Distrust in Power, Belief in the Fringe

Of course we should not forget there is another factor behind Plandemic‘s virality: the growing credibility gap between institutions and citizens. Decades of political disappointments—from the Vietnam War to the Iraq invasion—had already planted seeds of distrust. Neoliberal policies that prioritized market freedom over public welfare deepened social inequality, making many citizens feel unheard, unrepresented, and increasingly suspicious of authority. As Bennett and Livingston (2020) argue, people no longer see mainstream media or government as trustworthy mediators of truth. That’s what made the ground even more fertile for misinformation to spread.

The Role of Platforms: Amplifiers or Gatekeepers?

The World Health Organization (WHO) came up with the term “infodemic” to describe the flood of misinformation that spread during COVID-19 (van der Linden, 2022). Basically, it means we weren’t just dealing with a pandemic — we were also drowning in way too much information, much of it totally false or misleading. As journalist Kara Swisher (2021) put it, trying to fight misinformation by simply putting out “good information” is like trying to “hold back a stinky, raging ocean with just one tiny sandbag” — kind of hopeless, right?

generated by AI

Here’s the tricky part: in the middle of this overwhelming swirl of content, misinformation like Plandemic didn’t just get lost in the noise — it actually managed to stand out and go viral. How? To understand how Plandemic went viral so quickly, we also need to look at the mechanisms behind it. The video didn’t just spread by chance — it succeeded by using clever strategies and tapping into the core logic of social media platforms.

Too Viral to Kill:Bots, Superspreaders, and the Persistence of Misinformation

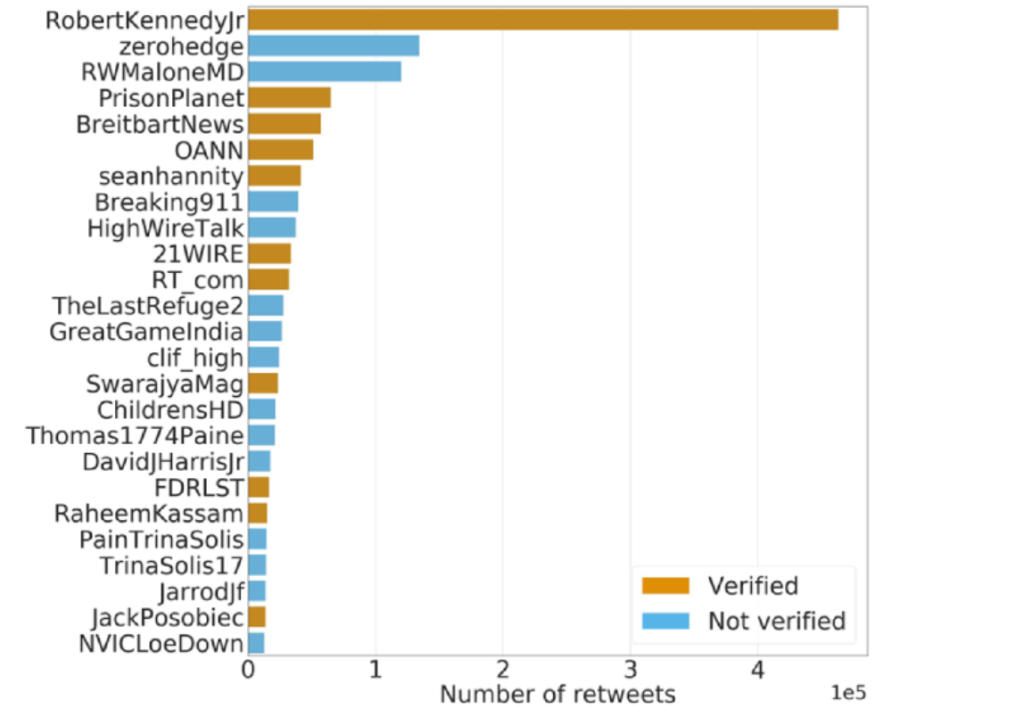

A small group of “superspreaders”—verified accounts and social bots—had outsized influence on how Plandemic traveled across networks (Pierri et al., 2023). Around 800 verified Twitter accounts made up a small but powerful group of “superspreaders,” responsible for about 35% of all misinformation reshares on an average day. Shockingly, just one account — @RobertKennedyJr — was behind over 13% of those retweets all by himself. What’s more, low-credibility news and sketchy YouTube videos were much more likely to be shared by automated accounts, hinting at some level of coordinated or even manipulated efforts behind the scenes.

Source: Pierri et al. (2023).

Besides, a lot of suspicious YouTube videos were shared on Twitter, showing just how easily this kind of content spills across platforms. Meanwhile, Twitter’s decentralized structure allowed information to flow across smaller communities, creating resilience against takedowns. Shahin and Pieters (2021) note that the film’s producer actively encouraged viewers to download and reupload the video, bypassing traditional moderation. Even after the video was removed, it continued to circulate through reuploads, private groups, and encrypted apps.

The Forbidden Fruit Effect: Why Censorship Made Plandemic Even More Tempting

When platforms finally acted, some users interpreted it as proof of censorship, triggering a “Streisand Effect” where efforts to suppress the content only increased its appeal (Kearney, Chiang, and Massey, 2020). “They keep pulling it down, which in and of itself tells you everything,” Seal, a singer in United States, said of efforts by YouTube and Facebook to halt the video’s widespread circulation.

Beyond Deletion: What Platforms Really Need to Do

Platforms acted too late, and too cautiously. Facebook insists it’s not in the business of being a “truth arbiter,” which is why it tends to avoid taking down most content outright (Iosifidis & Nicoli, 2020). Their reluctance to intervene decisively—whether due to fears of overreach, political backlash, or commercial interests—allowed harmful content to gain massive traction before any guardrails were put in place. In trying to remain “neutral,” platforms often end up being passive amplifiers of disinformation rather than responsible gatekeepers of public discourse. From this perspective, Biden’s sharp criticism of social media platforms doesn’t seem unjustified. Basic steps like identifying and reducing the visibility of superspreaders, deplatforming high-risk accounts, and downranking harmful content with clear warning labels are important—but they’re just the beginning.

To truly confront the disinformation crisis, platforms need to go further. This means actively shaping the information ecosystem by consistently de-amplifying harmful narratives, elevating trustworthy sources, and committing to transparency in how content is moderated and decisions are made.

Conclusion: Toward an Emotionally Resilient Public Sphere

The Plandemic episode reveals a disturbing truth: disinformation thrives not just on falsehoods, but on unmet emotional needs. In moments of crisis, people seek meaning, clarity, and belonging. When institutions fail to provide these, alternative narratives—even harmful ones—rush in to fill the gap.

To combat this, we need more than just fact-checking. We need to understand the emotional terrain of public life. Social media platforms must take more proactive steps to curb virality at the algorithmic level. Governments must work to rebuild public trust not just through transparency, but through genuinely inclusive policies. Public health communication should be empathetic, transparent, and rooted in two-way dialogue, not top-down decrees.

Ultimately, fighting disinformation means addressing the social and emotional wounds that make it so persuasive. Because in the end, it’s not just a battle over facts—it’s a battle over who gets to define the truth, and why people are so eager to believe it.

References

Alba, D. (2020, May 20). Virus conspiracies thrive, despite YouTube’s crackdown on “Plandemic”. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/20/technology/plandemic-movie-youtube-facebook-coronavirus.html

Becker1999. (2020, May 9). A child protesting COVID-19 vaccines with the word plandemic at Franklin County, Ohio [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%27Free_Ohio_Now%27_(Columbus)_bIMG_0868_(49876163551).jpg

Bennett, W. L., & Livingston, S. (Eds.). (2020). The disinformation age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Iosifidis, P., & Nicoli, N. (2020). The battle to end fake news: A qualitative content analysis of Facebook announcements on how it combats disinformation. International Communication Gazette, 82(1), 60–81.

Kearney, M. D., Chiang, S. C., & Massey, P. M. (2020). The Twitter origins and evolution of the COVID-19 “plandemic” conspiracy theory. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, 1(3).

Lorenz, T. (2020, June 8). How “Plandemic” and its falsehoods spread widely online. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/08/style/seal-instagram-stories-plandemic-coronavirus.html

MUBI. (n.d.). Plandemic. https://mubi.com/en/au/films/plandemic

Ovide, S. (2021, July 16). Biden vs. Facebook is a fight about the future of the internet. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/16/opinion/biden-facebook-covid-vaccine.html

Pierri, F., DeVerna, M. R., Yang, K. C., Axelrod, D., Bryden, J., & Menczer, F. (2023). One year of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on Twitter: Longitudinal study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, e42227.

Roose, K. (2020, June 27). A baseless conspiracy theory about the virus spread faster than the virus. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/27/technology/pizzagate-justin-bieber-qanon-tiktok.html

Shahin, N., & Pieters, T. (2021). Plandemic revisited: A product of planned disinformation amplifying the COVID-19 “infodemic”. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, Article 649930. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.649930

van der Linden, S. (2022). Misinformation: Susceptibility, spread, and interventions to immunize the public. Nature Medicine, 28(3), 460–467. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01713-6

Be the first to comment