Figure1. Friedman, J. (2024, October 29). Trouble with “truth decay”: combating AI and the spread of misinformation

Introduction: From “Pizzagate” to 5G rumors – Why is disinformation a modern disease?

In December 2016, a man with a firearm entered the Comet Ping Pong restaurant in Washington, D.C., believing he was there to “free” children supposedly held captive. The action arose from the “Pizzagate” conspiracy theory present on the Internet, and misinformation migrated from the virtual to the real world, which led to the shooting incident (Trending, 2016). The incident serves as an example of how violence can result from online rumours. The speed and scope of information are unparalleled in the digital age. Social media platforms use big data and algorithms to draw users in and keep them on the site. The content that attracts users and holds their interest usually comprises sensational, extreme, or emotional information, which largely supports the platform. This mechanism has led to more and more “fake news” appearing on social media. Behind fake news is the rapid spread of misinformation and false information, which seriously affects the public perception and the foundation of trust in society (Flew, 2021).

News about the “Pizzagate” story. Sky News. (2016, December 8). Fake news, pizza, and the Trump team [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S7Pq754KlLs

However, the spread of such misinformation and disinformation is not just a technical problem. It also reflects the interweaving of multiple factors, such as the platform economic model, institutional trust crisis, and human cognitive bias. The algorithmic design of social media platforms, combined with declining trust in traditional institutions, has created a “perfect storm” for the spread of disinformation in the digital age, where information spreads far faster than humans can verify it (Jack, 2017). This blog will explore how the spread of disinformation is not just a technical problem but a combination of platform business models, media misinformation, institutional failures, and human cognitive vulnerability. And how digital policy and governance can reduce or avoid these problems.

The ‘click business’ of the platform economy – how do algorithms contribute?

Sensational content frequently takes precedence over accurate and trustworthy information on social media platforms to increase user engagement and advertising revenue. This algorithmic preference can then tend to spread false information rapidly across the web. For example, in 2022, a false news story about ‘Disney lowering the drinking age to 18’ spread widely on TikTok, and although it originated on the satirical website Mouse Trap News, the platform’s algorithmic mechanism allowed it to spread quickly, leading to public misunderstanding (Mouse Trap News, 2022). Academic research has also suggested that platforms blur the lines between truth and lies by commodifying information based on the ‘attention economy’ (Flew, 2021).

Allcott and Gentzkow (2017) noted that pro-Trump fake news was shared on Facebook four times more than pro-Hillary fake news in their study of the 2016 US election. They argued that emotional engagement by users was more likely to embrace pro-Trump fake news. Thus, there is evidence supporting the role of algorithmic design in the spread of disinformation.

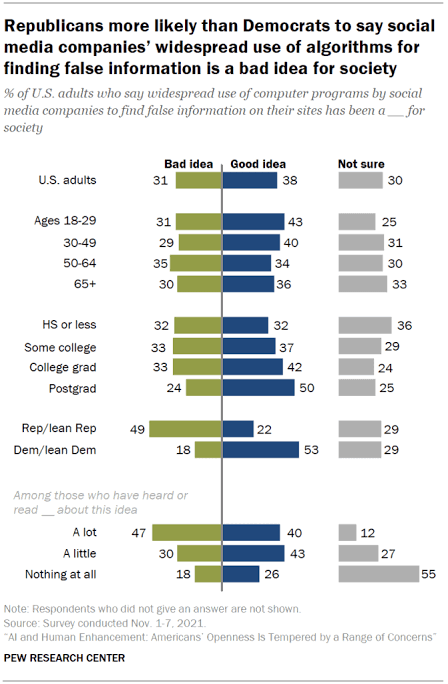

Figure2. American adults’ views on social media companies’ use of computer programs to spot disinformation. (Pew Research Center, 2022).

Analyzing the policy, Section 230 of the Communications Act of 1934 provides a protection for platforms as the Good Samaritan Clause, which protects them from liability for users’ content. (Section 230: An Overview, n.d.). This leaves platforms with little incentive to review content and no responsibility for the consequences of algorithmic pushing.

Therefore, platforms aren’t just neutral tech tools; their business models are deeply intertwined with the spread of disinformation. It’s crucial for governments and relevant regulatory bodies to think critically about and regulate how these algorithms are designed and how content is recommended.

Media misdirection: Profit-driven information distortion

Figure3. Rumors and fake news spread quickly in online media. (Knight Foundation, n.d.).

In this age of information overload, the role of media as a significant channel of information dissemination has become more and more complex. On the one hand, the media has the responsibility of communicating accurate and objective information. On the other hand, because it is more lucrative, some media, although they can provide accurate and objective information, opt to focus on what appeals to audience preferences and even disseminate exaggerated or fake information. This is particularly prevalent on social media. Many media sources engage in practices that sensationalize or exaggerate and use conspicuous language with the hopes of generating clicks. At the time of major events, some media sources often post inaccurate news before anything is confirmed in order to draw attention and create panic or controversy (Jack, 2017). Fake news frequently spreads six times faster than real news on social media platforms, making this phenomenon especially noticeable there (Vosoughi, Roy, & Aral, 2018).

The 2004 vaccine safety controversy, for instance, was sparked by British physician Andrew Wakefield’s research suggesting a connection between autism and the MMR vaccine. Following its release, the study was widely reported in various media and caused a great deal of public anxiety regarding vaccine safety (Rao & Andrade, 2011).

Even though multiple studies have found no association to date, persistent media reporting has lowered rates of vaccination and increased levels of susceptibility to outbreaks. Such media practices may generate traffic in the short term but ultimately cause erosion of trust in the media.

Breakdown of Trust: Why is traditional institutional authority failing?

It is precisely because the credibility of traditional authorities such as the government and the media, has declined, which provides soil for the spread of false information (Bennett & Livingston, 2020). In the case of COVID-19, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) first advised the public to wear masks in April 2020 but then adjusted its guidelines several times, causing the public to be skeptical of official information and turn to social media for answers (He et al., 2021). This has created conditions for the breeding of rumors such as “5G spread virus” and has triggered arson incidents targeting 5G base stations.

In 2016, only 32 percent of Americans trusted the media, and the figure was as low as 14 percent among Republican supporters, according to the study. Livingston and Bennett (2020) analyzed that in the era of information war, the decline of institutional trust is closely related to the rise of populism. Lazer et al. (2018) also emphasize that emotional resonance often trumps fact-checking in a “post-truth” environment.

The European Union’s Digital Services Act (DSA) requires platforms to disclose their algorithms and content governance processes, aiming to rebuild user trust in platforms by increasing transparency (The Impact of the Digital Services Act on Digital Platforms, n.d.). However, the performance of the platforms has been very bad as they have not filled the institutional trust vacuum, lacking in accountability and transparency as well.

Human weakness: The role of cognitive bias and the need to belong to a community

Figure4. Cognitive Bias Codex. (Initiative, 2021).

The human wish to belong to a community and cognitive bias combine to create a psychological incubator for the proliferation of misinformation. Pioneering research by Pennycook and Rand (2018) showed that people’s belief in disinformation is usually not a function of their political orientation, but rather that people lack analytical habits of thought – a mechanism teams refer to as cognitive inertia. This psychological mechanism occurred for example COVID-19 pandemic: the rumor that “vitamin C can cure COVID-19” spread rapidly throughout social networks and was disseminated widely by groups who had accomplished higher levels of education (Wang et al. 2020). This shows an almost counter-intuitive underlying truth that the body of knowledge is not protected from misinformation, and rational judgment can often be defeated by emotional needs, especially if the content meets an individual’s urgent need for a sense of control.

An even more extreme case is the spread of the QAnon conspiracy theory. The premise of this fantasy narrative, which asserts that Trump is secretly battling “Satanic elites,” has drawn millions of followers in large part because it effectively taps into three psychological vulnerabilities of modern man: the craving for simple explanations; a suspicion of authority; and most importantly, the desire for belonging (Van Prooijen, 2022). Research has shown that many supporters are first attracted by some form of reassurance in “finding someone who gets it” but quickly become enamored with more extreme forms of content through algorithmic recommendations, approaching an impenetrable information cocoon (Marwick, 2021).

Data & Society’s Dictionary of Lies project (Jack, 2017) systematically reveals the mechanisms by which misinformation spreads, from “fragments of fact” that exploit confirmation bias to pseudo-profound statements that rely on emotional resonance. These findings point to a key conclusion: Countering disinformation requires a two-pronged approach – both through education that cultivates critical thinking and the structural incentives of platform algorithms that must be reformed. Placing the blame solely on individuals is not only unjust, but also doomed to futility.

Governance dilemma: the game between platform power, freedom of speech and public interest

In the digital age, social media platforms play a key role in the dissemination of information. However, existing regulatory models struggle to strike a balance between platform power, freedom of expression, and public interest (Flew, 2021). The 2016 “Pizzagate” incident, for instance, demonstrated the limitations of post-facto supervision when Facebook deleted the pertinent false information after the fact but was unable to stop the actual violence. The United States Communications Decency Act’s Section 230, which protects platforms from being held accountable for user-generated content, has both fueled the Internet’s growth and sparked worries about a lack of accountability. On the other hand, the European Union’s Digital Services Act (DSA) imposes new obligations on “very large platforms” related to algorithmic risk assessments and third-party audits, with the intent of creating greater transparency and accountability (The Impact of the Digital Services Act on Digital Platforms, n.d.). However, cross-border enforcement and guarantees of freedom of expression remain implementation challenges.

Jack (2017) recommends differentiated governance strategies for different types of disinformation (false, intentionally misleading, and outright fabricated). This demonstrates the complexities of trying to balance platform power with the public good. Adopt differentiated governance strategies for different types of disinformation (e.g., misinformation, malicious misinformation, outright fabrication) in order to balance regulation with freedom of expression.

Conclusion: Rebuilding information ecology: a multi-level action initiative

A comprehensive strategy at the individual, platform, and systemic levels is required to address the problem and harmful impacts of disinformation. Establishing “information hygiene” practices—such as taking a moment to consider the information before sharing, carefully considering its content, verifying information from several sources, and fact-checking for accuracy (e.g., PolitiFact, Snopes)—is crucial to achieving this on an individual basis. The spread of false information can be lessened at the institutional and platform level by making algorithms more transparent, making recommendations and risk reporting public, and setting up alerts to remind users to exercise caution and double-check information (also known as “accuracy nudge”). At the institutional level, support the government’s efforts to enact or amend provisions such as the implementation of the Digital Services Act and reforms to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, establish a dynamic regulatory and accountability framework, and fund independent fact-checking organizations and media literacy programs to promote digital literacy. As the study points out, considering the human behind the screen before sharing information, our trust and judgment are the last line of defense for information ecology.

References

Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211-236. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211

Flew, T. (2021). Disinformation and fake news. In Regulating platforms (pp. 86-91). Polity Press.

Friedman, J. (2024, October 29). Trouble with “truth decay”: combating AI and the spread of misinformation – Law Society Journal. Law Society Journal. https://lsj.com.au/articles/trouble-with-truth-decay-combating-ai-and-the-spread-of-misinformation/

He, L., He, C., Reynolds, T. L., Bai, Q., Huang, Y., Li, C., Zheng, K., & Chen, Y. (2021). Why do people oppose mask-wearing? A comprehensive analysis of U.S. tweets during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 28(7), 1564–1573. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocab047

Initiative, Y. L. O. T. A. (2021, September 26). Looking inward in an era of ‘fake news’: Addressing cognitive bias – Young Leaders of the Americas Initiative. Young Leaders of the Americas Initiative. https://ylai.state.gov/looking-inward-in-an-era-of-fake-news-addressing-cognitive-bias/

Jack, C. (2017, August 9). Lexicon of lies. Data & Society. https://datasociety.net/library/lexicon-of-lies

Knight Foundation. (n.d.). Study shows how misinformation spreads online and fuels distrust. https://knightfoundation.org/articles/study-online-disinformation-fuels-mistrust-of-science/

Lazer, D. M. J., Baum, M. A., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F., Metzger, M. J., Nyhan, B., Pennycook, G., Rothschild, D., Schudson, M., Sloman, S. A., Sunstein, C. R., Thorson, E. A., Watts, D. J., & Zittrain, J. L. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359(6380), 1094-1096. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao2998

Livingston, S., & Bennett, W. L. (2020). A brief history of the disinformation age. In S. Livingston & W. L. Bennett (Eds.), The disinformation age (pp. 3-40). Cambridge University Press.

Marwick, A. (2021). Morality, authenticity, and behavioral change: How QAnon gets into people’s heads—and what that means for platform governance. International Journal of Communication, 15, 1517–1539. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/1611

Mouse Trap News. (2022, December 24). Drinking Age at Disney World May be Lowered to 18. Mouse Trap News. https://mousetrapnews.com/drinking-age-at-disney-world-may-be-lowered-to-18/

Nadeem, R., & Nadeem, R. (2024, July 22). 3. Mixed views about social media companies using algorithms to find false information. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2022/03/17/mixed-views-about-social-media-companies-using-algorithms-to-find-false-information/

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2018). Lazy, not biased: Susceptibility to partisan fake news is better explained by lack of reasoning than by motivated reasoning. Cognition, 188, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.06.011

Pew Research Center. (2022, March 14). Republicans more likely than Democrats to say social media companies’ widespread use of algorithms for finding false information is a bad idea for society | Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2022/03/17/mixed-views-about-social-media-companies-using-algorithms-to-find-false-information/ps_2022-03-17_ai-he_03-05-png/

Rao, T. S., & Andrade, C. (2011). The MMR vaccine and autism: Sensation, refutation, retraction, and fraud. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 53(2), 95. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.82529

Section 230: An overview. (n.d.). Congress.gov | Library of Congress. https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46751

Sky News. (2016, December 8). Fake news, pizza, and the Trump team [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S7Pq754KlLs

The impact of the Digital Services Act on digital platforms. (n.d.). Shaping Europe’s Digital Future. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/dsa-impact-platforms

Trending, B. (2016, December 2). The saga of “Pizzagate”: The fake story that shows how conspiracy theories spread. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-38156985

Van Prooijen, J.-W. (2022). The role of social identity in conspiracy beliefs. In Psychological origins of conspiracy beliefs (pp. 45-68). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009082525

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146–1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

Wang, Y., McKee, M., Torbica, A., & Stuckler, D. (2020). Systematic literature review on the spread of health-related misinformation on social media. Social Science & Medicine, 240, 112552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112552

Wendling, B. M. (2021, January 6). QAnon: What is it and where did it come from? https://www.bbc.com/news/53498434

Be the first to comment