Introduction

Deepfake Technology

Imagine: there is a video of a world leader declaring war on the Internet. News agencies scramble to report, and social media collapses. However, just a few hours later, people finds that the video is generated by AI.

This is not a scene in a science fiction movie or a Hollywood gimmick – this is today’s reality. In current digital world, seeing is no longer believing.

More importantly, we are not just facing a technological problem; we are facing what Benkler et al. (2018) call an epistemological crisis. Specifically, this refers to a breakdown in the public’s ability to distinguish fact from fiction, truth from manipulation (Benkler et al., 2018).

Deepfakes are not only boring entertainments, but also a key tool in the dissemination of disinformation, misinformation, and fake news, posing a significant threat to cyber-security and media trust. While several countries are struggling to regulate it, the methods are very different.

Next, I will uncover the dangers of deepfakes and compare how different countries – especially the United States and China – are attempting to regulate this emerging threat through laws and policies. Basically, deepfake is a warning signal that we are losing truth control of the Internet age.

What Are Deepfakes? Why Are They Dangerous?

In today’s world, you can not always believe what you see or hear – deepfakes are rapidly becoming one of the most disturbing technologies of our time. But what exactly are they?

Deepfakes refer to the use of artificial intelligence (especially deep learning) to manipulate video, audio or images, which can replace people in existing images or videos with someone else (Seow et al., 2022). Deepfakes are incredibly realistic, especially when people watch them quickly or out of context.

At the beginning, deepfakes seemed like a harmless novelty – think funny celebrity face swaps or parodies.

But according to Vaccari and Chadwick (2020), as the technology grows more powerful and popular, the boundary between entertaining editing and dangerous deception has almost disappeared. This technology quickly becomes a serious tool for manipulation and exploitation, spreading disinformation, misinformation and fake news.

Some of the most common and disturbing uses include: fake videos of politicians and head-swapping porn videos of people, especially women. The technology is now so readily available that anyone with a laptop can create one.

Political Manipulation

The emergence of deepfakes provides a new way for political manipulation and poses a major threat to the democratic process.

In March 2022, a chilling video circulated online in which Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy appeared to be calling on his troops to lay down their weapons and surrender to the Russian army (The Telegraph, 2022). The video was briefly broadcast by a hacked Ukrainian news channel and posted on social media, but it was soon revealed that it was deepfaked (Wakefield, 2022). The purpose is to shake morale and spread chaos during the war.

Female Exploitation

Another dark use of deepfakes: the production of pornographic content without consent, causing serious psychological and reputational damage to the victims.

In recent years, fake nude photos and videos of female celebrities and influencers have spread like wildfire on platforms such as Reddit and Twitter. Artificial intelligence tools can generate fake private content with just a few selfies.

The tragic experience of Hannah Grundy, a 35-year-old school teacher from Sydney, is a typical example of this problem. Hannah found that Andy Hayler — a close friend who she had known for ten years, had superimposed her face with explicit images and shared them online (Turnbull, 2025).

Andy had digitally edited and posted hundreds of photos of Hannah

In this regard, Hannah expressed a deep sense of being violated:

“I stopped having the windows open because I was scared… maybe someone would come in”.

This caused immense emotional damage to Hannah and her husband, leaving them in constant fear and spending over $20,000 to seek justice.

These examples reveal how deepfakes erode the media trust. And what is the most dangerous part?

It is not just forging something, but more importantly, it makes people doubt the truth. Because videos, audios, and photos can now be forged realistically, anyone can claim: “That is not me, that is deepfaked!” This is a dangerous loophole that can be exploited by perpetrators to deny true evidence and create confusion.

As Waisbord (2018) argues, we live in a “post-truth” world where truth becomes subjective and facts are seen as partisan or ideological. This means that the more deeply falsified disinformation, misinformation and fake news are disseminated, the more fragile our common reality is.

🌐 Regulating Deepfakes—A Global Overview: Compare how the U.S. and China are tackling (or struggling to tackle) the deepfake problem.

So, how do governments deal with it?

Let’s take a look at how the two major political bodies are tackling the deepfake problem, which reveals their broader attitudes towards disinformation, misinformation, fake news, and truth.

🇺🇸 United States: Free Speech and Fragmented Responses

Given that the United States regulators are rooted in the constraints of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution: “Congress shall make no law . . abridging the freedom of speech” (Analysis and Interpretation of the U.S. Constitution, n.d.). This tradition puts the United States in a tricky position when it comes to regulating speech, even for those that are harmful or deceptive.

The DEEP FAKES Accountability Act (H.R. 3230), proposed at the 116th Congress in 2019, is designed to address the challenges posed by deepfakes. Although the bill failed to pass in the end, it set an important precedent.

Key provisions of the bill include:

- 1. Disclosure Requirements: Creators of deepfake content would be mandated to include a clear and conspicuous disclosure, informing the audience that this content has been tampered with or generated by artificial intelligence.

- 2. Criminal Penalties: The bill proposes the establishment of criminal penalties for individuals who knowingly fail to make the required disclosures, particularly if the deepfake is created with the intent to facilitate criminal or intelligence activities.

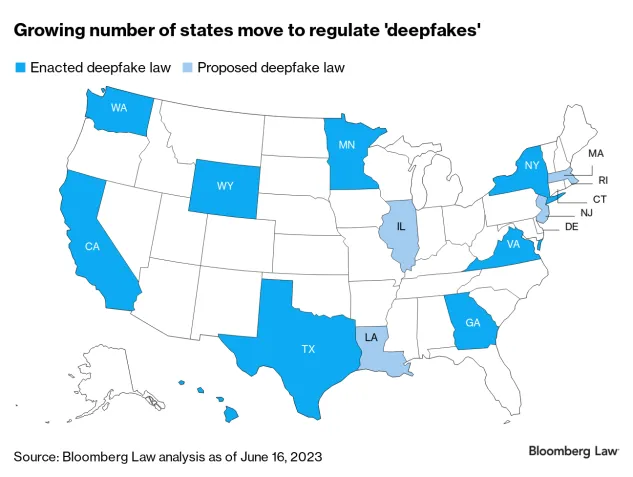

In the absence of the relevant laws of the federal government, the states of the United States have intervened one after another, but the results are uneven:

- Texas stipulates that the following acts are criminal offenses:

- California, on the other hand, the following acts are restricted:

- 1. Use artificial intelligence to replicate the voice or likeness of actors and performers without their consent is illegal;

- 2. Large online platforms should remove or clear label deceptive, digitally altered, or fabricated content related to elections within a specified time frame;

- 3. The creation or distribution of non-consensual deepfake pornography, especially when it causes significant emotional harm to the victim is illegal.

Growing number of states move to regulate “deepfakes”

In fact, the United States’ countermeasures against deepfakes can be described as “patchwork” – fragmented, passive, and increasingly unable to keep pace with the speed of technological developments. While some states, such as Texas and California, have taken measures in the specific context of election interference and the distribution of non-consensual pornography to regulate deepfake problems. To date, however, there is no comprehensive federal law in the United States that directly and comprehensively regulates the issue of deepfakes.

This fragmented legal environment leaves obvious loopholes. For example, an explicitly fake image may be illegal in California, but not in another state. A politically motivated deepfake may be prosecuted in Texas but go unpunished elsewhere. Victims face a chaotic situation of inconsistent protection measures, while perpetrators continue to take advantage of the lack of geographical boundaries of the Internet. Crucially, platforms that host and amplify such content usually bear only minimal responsibility and are supervised by themselves.

This uncoordinated approach is particularly dangerous because deepfakes themselves have no national borders. Without coherent national legislation and effective enforcement mechanisms, the ability of the United States to protect its citizens, democracy and cyber-security may fall further behind.

If the United States wants to seriously deal with the problem of deepfakes, it must go beyond passive measures and formulate a unified federal strategy. Freedom of speech should also be protected in the digital age, but not at the expense of truth, cyber-security and justice.

🇨🇳 China: Censorship and Control

Unlike the United States, China has established a comprehensive regulatory framework to govern the use of deepfake technology. For example, in 2019, the face-swapping app ZAO became popular for allowing users to insert their faces into film scenes. However, users must allow the application to use their facial data without restrictions, agreeing to overly broad terms. Eventually, with the intervention of the Chinese government, ZAO was forced to modify its data policy (Agence France-Presse in Shanghai, 2019).

ZAO was forced to modify its data policy in China

Subsequently, in January 2023, China officially implemented the Administrative Provisions on Deep Synthesis in Internet-Based Information Services (Cyberspace Administration of China, 2022), putting forward strict requirements on AI-generated content.

According to these regulations:

- User Identity Verification: Deep synthesis service providers are required to verify users’ real identities through methods such as mobile phone numbers or identification card numbers;

- Content Management and Censorship: Providers must not use deep synthesis services to produce, reproduce, publish, or transmit information prohibited by laws or administrative regulations. This includes content that endangers national security, harms the nation’s image, or disrupts economic or social order. Platforms are obliged to detect, report, and remove such harmful content;

- Watermarking and Disclosure: AI-generated content must be clearly labeled to indicate its synthetic nature;

- Consent for Biometric Data Use: When deep synthesis services involve editing a person’s biometric information, such as facial features or voice, providers must obtain the individual’s explicit consent;

- Algorithmic Transparency: Deep synthesis service providers are mandated to establish and disclose management rules and platform covenants, improve service agreements, and fulfill management responsibilities in accordance with the law.

The implementation of these regulations is centrally managed by the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), which cooperates with law enforcement departments to jointly supervise compliance with regulations. While the regulations have been effective in curbing the dissemination of synthetic media, this effectiveness comes at a cost. These provisions intersect with broader legislation such as the National Security Law and the Data Security Law, giving the authorities broad discretion to define and suppress “disinformation”, “misinformation”, and “fake news”.

According to the International Federation of Journalists (2023), the Chinese government uses this legal ambiguity to mark dissent/critical news reports as disinformation/fake news, rationalizing these behavior as necessary to maintain public order. This has expanded the crackdown and suppression of independent media and unauthorized media workers.

As such, China’s regulatory framework is also a powerful tool for censorship and political control, which has raised concerns about political manipulation and the suppression of dissent. This is less about protecting the truth than about reinforcing the national narrative.

🔚 Conclusion: A War on Truth — And Why It Matters

Deepfake technology is not just a cool technological trick or a popular internet trend, but also flashes like a red light, alerting us that people’s most basic trust in the truth is being threatened.

Countries around the world are struggling to tackle the deepfake problem. The United States, with its firm commitment to freedom of speech, has adopted a fragmented approach. In contrast, China has established one of the strictest regulatory frameworks, but its aim is not only to combat disinformation, misinformation, and fake news. In many cases, it also involves controlling narratives, suppressing dissent and consolidating state power.

But it is not just a problem of deepfakes. The real problem is: What are we supposed to believe?

When anyone can make a convincing fake video, when anyone can claim that the real video is fake, we will begin to doubt everything. This is the most terrible thing. Deepfakes not only spread lies, but also make it easier for people to ignore the truth. In a world where seeing is believing, that is a dangerous shift.

Try to find a Truth

So what can we do?

Yes, we need better laws. But we also need more:

- 1. Teaching media literacy in schools so the next generation knows how to question what they see;

- 2. Supporting independent journalism so people can access facts that are not filtered by algorithms;

- 3. Rethinking platform design so truth takes precedence over clicks and engagement;

- 4. Investing in technology, using tools to detect deepfakes or verify real content;

- 5. International collaboration – because deepfakes do not respect borders.

Deepfake is a wake-up call. It tells us that it is time to rebuild the way we trust, verify and share information online. Because if we can not distinguish the truth, we will lose control not only of our newsfeeds, but also the foundation of democracy, public debate and interpersonal connections.

Ultimately, the question is not whether we can identify deepfakes, but whether we can still identify the truth.

References:

Agence France-Presse in Shanghai. (2019, September 2). Chinese deepfake app Zao sparks privacy row after going viral. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/sep/02/chinese-face-swap-app-zao-triggers-privacy-fears-viral

Analysis and Interpretation of the U.S. Constitution. (n.d.) First Amendment. https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/amendment-1/

Benkler, Y., Faris, R., & Roberts, H. (2018). Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cyberspace Administration of China. (2022, December 11). Administrative Provisions on Deep Synthesis in Internet-Based Information Services. https://www.cac.gov.cn/2022-12/11/c_1672221949354811.htm

DEEP FAKES Accountability Act 2019 (USA.).

International Federation of Journalists. (2023, March 3). China: Beijing extends crackdown on independent media and ‘unauthorised’ media workers. https://www.ifj.org/media-centre/news/detail/article/china-anti-journalist-and-fake-news-campaign-to-continue-in-2023

Seow, J. W., Lim, M. K., Phan, R. C. W., & Liu, J. K. (2022). A comprehensive overview of Deepfake: Generation, detection, datasets, and opportunities. Neurocomputing (Amsterdam), 513, 351–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2022.09.135

The Telegraph. (2022, March 17). Deepfake video of Volodymyr Zelensky surrendering surfaces on social media. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X17yrEV5sl4

Turnbull, T. (2025, February 9). Woman’s deepfake betrayal by close friend: ‘Every moment turned into porn’. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cm21j341m31o

Vaccari, C., & Chadwick, A. (2020). Deepfakes and Disinformation: Exploring the Impact of Synthetic Political Video on Deception, Uncertainty, and Trust in News. Social Media + Society, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120903408

Waisbord, S. (2018). The elective affinity between post-truth communication and populist politics. Communication Research and Practice, 4(1), 17–34.

Wakefield, J. (2022, March 18). Deepfake presidents used in Russia-Ukraine war. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-60780142

Be the first to comment