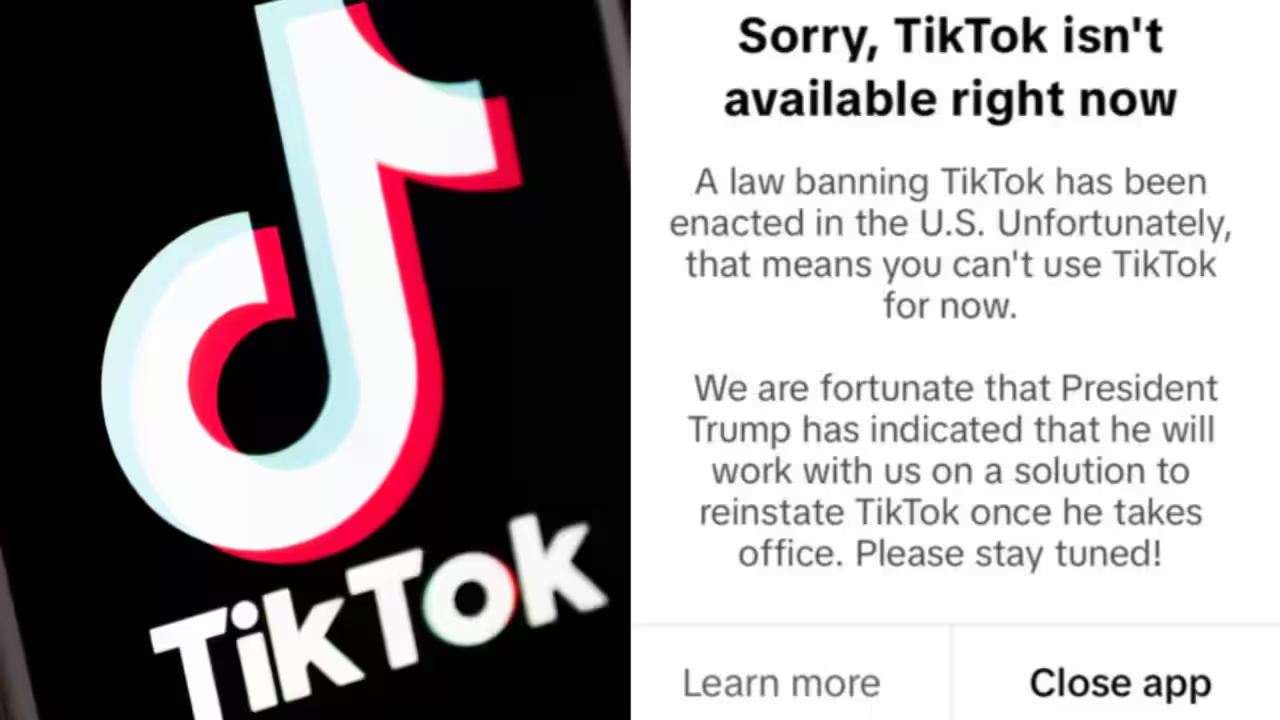

Imagine this: the social media app you use the most—TikTok—suddenly becomes inaccessible overnight. All your created videos, interactions with friends, and the fanbase you worked hard to build are gone. The government says this is to protect your privacy and national security. Sounds reassuring, doesn’t it? But the issue runs deeper. While officials claim to protect your personal data, these actions may quietly take away some of your rights—not just your privacy, but also your freedom to choose platforms and take part in the global digital space.

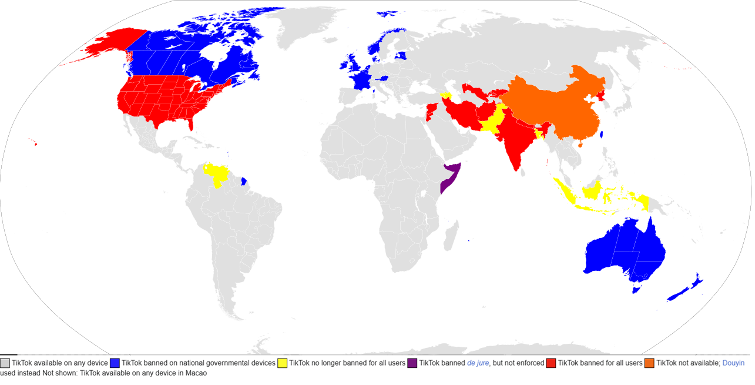

In recent years, countries like the United States, the European Union, and Australia have started to censor or even ban TikTok under the banner of “privacy protection” and “national security.” Scholars have critically examined this trend. Flew (2021) argues that digital rights are not just about privacy. They cover a broader field, including freedom of expression and the flow of data across borders. These rights also include the freedom to choose platforms and access information. Suzor (2019) warns that the rules of digital platforms are often set without public input, slowly eroding users’ autonomy in online spaces. Goggin and colleagues (2017) add that for marginalized groups, the right to participate in global digital platforms is especially vital, since these platforms often serve as rare spaces for expression and visibility.

This blog takes the TikTok ban as a case study to explore how platform restrictions—justified by privacy and national security—can limit our digital autonomy. More importantly, it raises a critical question: in the push to protect our privacy, what exactly are we giving up?

When Privacy Becomes “National Security”

On social media platforms—especially ones like TikTok—user data isn’t just personal property. It has become a political and commercial asset (Trifiro, 2022). In a world shaped by rapid digital globalization, governments have grown increasingly concerned that data collected by such platforms could be used in harmful ways, especially when the platform is tied to a foreign company or state. TikTok, owned by the Chinese company ByteDance, has become a key target for such scrutiny. Countries like the United States worry that the platform’s handling of user data may pose national risks, from influencing political opinion to enabling espionage.

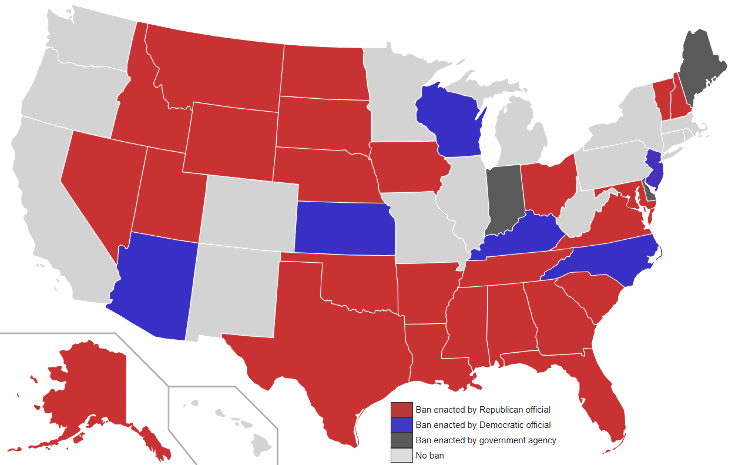

The U.S. government’s concerns about TikTok go back several years. Since 2019, multiple agencies have flagged it as a security risk, warning that sensitive data from American users might be passed to the Chinese government. The Trump administration even tried to force ByteDance to sell its U.S. operations, framing the platform as a tool for Chinese political interference. While the Biden administration took a slightly different approach, the Commerce Department in 2023 still named TikTok a major national security threat and launched ongoing investigations into its data practices.

Similarly, the European Union has launched its own inquiries, focusing on whether TikTok is in violation of the General Data Protection Regulation (Suzor, 2019). Australia, too, has raised concerns about how TikTok handles local user data and its potential links to the Chinese government.

But behind these national security measures lies a deeper and more complex issue: data sovereignty and platform governance. Flew (2021) explains that data sovereignty isn’t just about governments controlling where and how data is stored. It also concerns ensuring that data isn’t misused by foreign entities. Platform governance, on the other hand, refers to how global platforms are managed and regulated, often across borders. This includes creating shared rules to protect users’ data and privacy (Goggin et al., 2017). However, when governments use “national security” as a catch-all justification, they risk overlooking a broader dimension of data sovereignty—the rights of ordinary users to choose, speak, and participate freely in digital spaces.

Safety or Control? The Hidden Costs of Protection

In discussions regarding platform governance and privacy rights, U.S. scholar Shoshana Zuboff introduced surveillance capitalism as an analytical starting point. She asserts that modern technological platforms collect, predict, and influence user practices and that privacy is commodified, bought, and sold (Zuboff, 2019). However, Zuboff cautions that simply swapping corporate surveillance for state surveillance still does not address the growing problem, as governments become new surveillance actors.

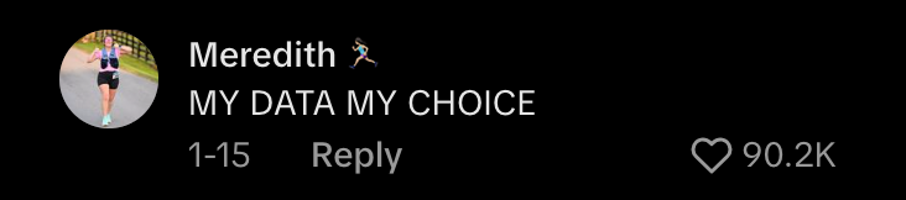

Following Zuboff, legal scholar Julie E. Cohen defines informational self-determination as a belief that individual users should exert control over how their data are collected, used, and shared online (Cohen, 2012). She argues that “privacy is not to be isolated from society”—the goal is to give agency to act and express oneself. When states intervene and block platforms, they act in a way that violates users’ rights to information and choice, therefore excluding users from participating in conversations about how digital spaces should be governed.

So, when TikTok banned in certain countries, the ones who feel the impact most are often everyday users—especially marginalized communities and cross-cultural immigrant groups. Marino (2024) points out that, in connection to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, TikTok emerged as an instrumental platform for refugees to tell their stories and plead for international assistance. Within this contextual understanding, the platform was not being used for entertainment—TikTok operated as a digital dwelling, a platform where users could share, express, and connect with their identity and public.

Once such a platform is banned, these users often don’t have a comparable alternative. Despite what governments might assume, users can’t always “just switch to another app.” Their relationship with the platform goes far beyond the technical—it’s social, emotional, and even professional. Trifiro (2022) notes that many TikTok users aren’t just consuming content. They’re building social networks and professional identities. Losing that space overnight is like being forced to leave a familiar digital city.

So, we need to ask a core question: Should real digital safety come at the cost of user freedom?

Privacy Isn’t Your Only Right Online

When we hear the term “digital rights,” most people probably think of privacy—like whether their personal data is being stolen or if they’re being watched. But digital rights go far beyond that. Just as we have the right to speak, protest, or read freely in the real world, we also have rights as digital citizens. And these rights aren’t just about being protected—they’re also about being included, being heard, and being able to participate.

Digital rights include two key types (UN Human Rights Council, 2014):

| Negative rights | freedom from harm, like not being tracked or having your data misused |

| Positive rights | freedom to act, like expressing opinions, accessing information, and joining public conversations (Access Now, 2020) |

UNESCO (2021) has warned that using “security” as a reason to control platforms risks narrowing public expression and cultural diversity. The European Digital Rights group (EDRi) criticizes some countries for building “sovereign walled gardens” in the name of privacy. Groups like Access Now argue that freedom of expression and community participation are just as important as privacy—especially during times of conflict or crisis, when platforms can be lifelines for survival. The EU is slowly shifting from “data protection” to “data empowerment”—a vision where people don’t just defend their data but decide how it serves them.

So next time we hear, “We’re blocking this app to protect your privacy,” we should also ask: What else are we losing? Not every promise of security is a gain in freedom. A truly democratic digital future should give us more rights—not take them away.

It’s Not Just an App—It’s Where We Live

Think of it in this way: your town has one main public square where people gather and talk. One day, the government shuts it down for “safety reasons.” Maybe their intention is good—but now you’ve lost the only space where you can speak, connect, and be seen.

TikTok is that kind of digital square, especially for groups often left out of mainstream media—LGBTQ+ users, refugees, second-generation immigrants, BIPOC creators. On TikTok, they find visibility, support, and a sense of community. When governments block the app in the name of national security, what’s lost isn’t just an entertainment platform—it’s a voice, a space, and a connection.

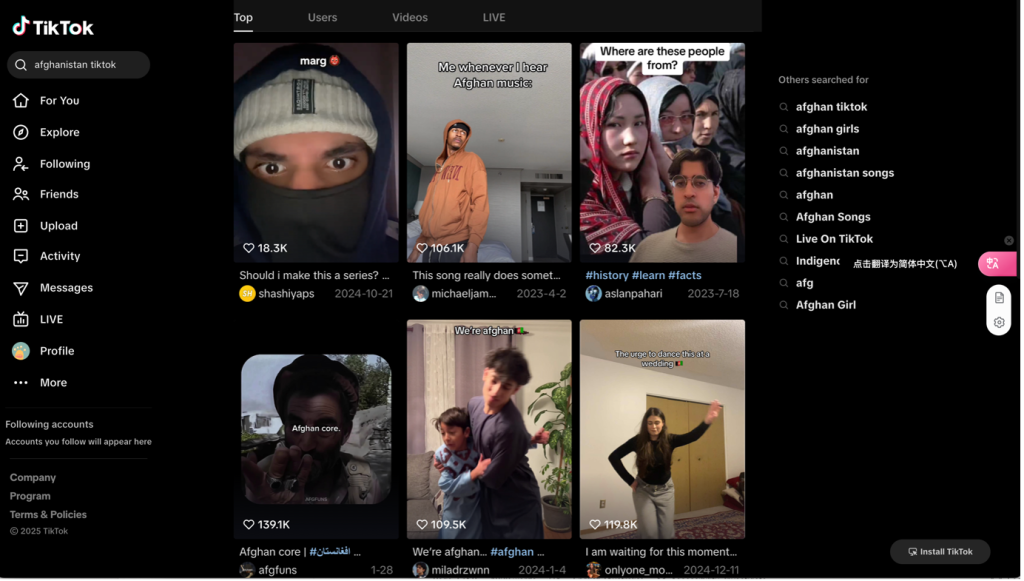

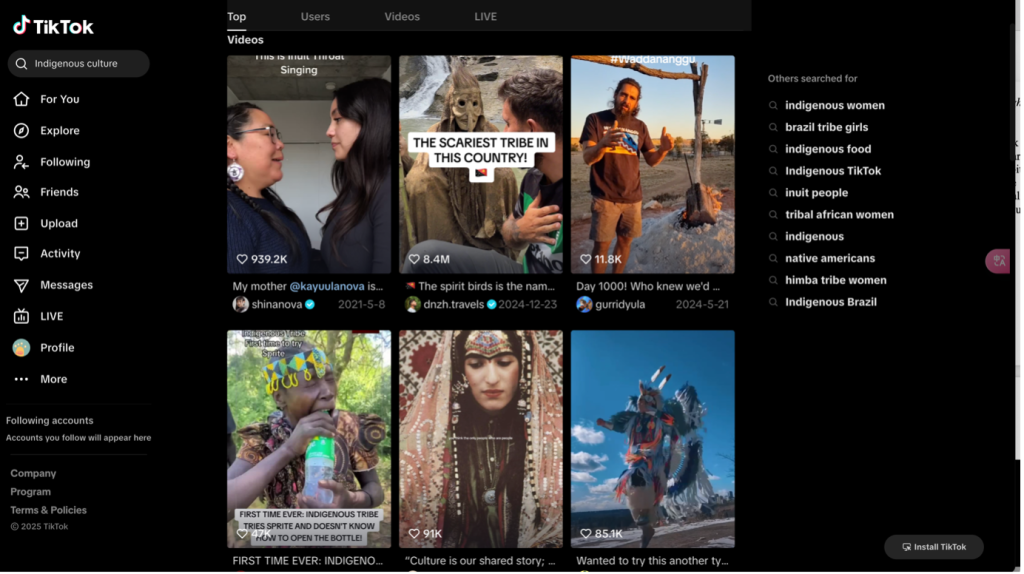

During global refugee crises, young people from Afghanistan or Syria have used TikTok to share their daily lives, their struggles, and family memories. These videos have drawn large waves of support and attention (Gillespie, 2022). For them, it’s more than storytelling—it’s reclaiming their identity through self-narration. Similarly, non-white communities in the West—Asian, Black, Indigenous—have used TikTok to share cultural dances, traditional foods, and personal stories of discrimination.

Australian scholar Crystal Abidin calls TikTok a micro-public sphere, a digital space where minority groups engage with public discourse on their own terms (Abidin, 2021). When such a platform is banned, what disappears is not just content—it’s visibility, and the right to be seen and heard. Also, some scholars call this phenomenon platform-enabled cultural sovereignty—the use of digital platforms by marginalized communities to claim voice, autonomy, and cultural space (Matamoros-Fernández & Farkas, 2021).

We need to rethink what platforms really offer. Their value isn’t just economic or political—it’s human. So, when a government blocks a platform, we shouldn’t only ask, “Did it protect national security?” We should also ask, “Who just lost their chance to speak?”

Don’t Just Protect Us—Empower Us

In the controversy over TikTok’s ban, governments always emphasized “protection” – protecting national security, protecting data from being abused by foreign governments, and protecting our privacy. But the real question is: What is the cost of that protection? Do we have to make a choice between “security” and “freedom”? If the answer is “yes”, then we may have to admit that the current digital policies do not protect each of us, but rather the state’s control over data and platforms.

Taking “data sovereignty” as an example, this term is often used in national policies as “the state’s control over data” (data sovereignty), but from the perspective of citizens, it should refer to: whether individuals can decide who can use their data, how to use it, and for what purposes (Cohen, 2019). Nissenbaum (2018) emphasizes that the state’s intervention in platforms should not ignore the right and control of ordinary people over the use of their data. Karppinen (2017) further pointed out that the governance of digital platforms should not be purely in the name of security but should balance the relationship between user freedom and privacy protection to ensure that users’ participation rights in the global digital space are not overly restricted.

Banning an app may just be a political move, but the long-term impact it brings is: digital life is increasingly like a “sovereign-style walled garden”, with cameras behind every door and reviewers behind every platform. What is more worrying is that “platform freedom” is constantly shrinking. When the government can unilaterally ban a platform or require the platform to conform to a certain political stance, users’ choice rights in the digital space also disappear. And this is precisely one of the basic freedoms in the digital age: the right to choose which tool to use to express oneself, with whom to connect, and to establish communities on which platform.

Digital rights organizations such as Access Now and EDRi have repeatedly called for: digital policies should not only start from the “defensive” perspective, but also consider “empowerment“, encouraging diversity, transparency, and user autonomy (EDRi, 2022).

What we truly need is not only a country with “banning power”, nor a platform that only “attracts users”, but a new framework of digital governance – one that can protect users and allow us to make autonomous choices, freely connect. For example:

Data can be taken away, just like you can take away furniture when moving.

Platforms can be switched, just like you can choose different supermarkets to shop.

Even between different countries, you can access the same app and keep in touch with friends far away, rather than being blocked by digital borders.

True digital citizens are not “passively protected people”, but “people who have the ability to choose, speak, and migrate”.

Words in the end

When governments restrict platforms in the name of “security,” they claim to be protecting us from data misuse. But the ones left out are often the users themselves. The TikTok debate isn’t just about geopolitical rivalry—it reveals a deeper issue: who holds power in the digital space?

If governments can easily ban platforms, and if platforms can freely change algorithms, privacy terms, or even erase our content, then we are not digital citizens—we’re digital subjects. Managed, stripped of choice, and left waiting for decisions made without us. That’s not the future we should accept.

A fair and sustainable digital ecosystem must be built on user participation. We don’t need states to choose for us. We need clear, transparent systems of governance—ones where platform users, developers, and community groups all have a seat at the table. Only by combining legal frameworks, technological design, and social collaboration can we create a truly participatory model of digital rights.

TikTok’s controversy might just be the beginning. It reminds us that digital rights are not gifts from above—they are rights we must claim. What we need is not just the right to be protected, but the power to speak, move, and participate fully as digital citizens.

References

BBC News. (2025, March). Who might buy TikTok as ban deadline looms? Amazon joins bidders. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/clyng762q4eo

BBC News. (2023, February 28). Is TikTok really a danger to the West? https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-64797355

Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2023). TikTok and national security. https://www.csis.org/analysis/tiktok-and-national-security

Clausius, M. (2022). The banning of TikTok, and the ban of foreign software for national security purposes. Washington University Global Studies Law Review, 21(2), 273–292.

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms (pp. 72–79). Polity Press.

Goggin, G., Vromen, A., Weatherall, K., Martin, F., Webb, A., Sunman, L., & Bailo, F. (2017). Executive summary and digital rights: What are they and why do they matter now? In Digital rights in Australia. University of Sydney. https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/17587

Karppinen, K. (2017). Human rights and the digital. In H. Tumber & S. Waisbord (Eds.), The Routledge companion to media and human rights (pp. 95–103). Routledge.

Liu, G. L., Zhao, X., & Feng, M. T. (n.d.). TikTok refugees, digital migration, and the expanding affordances of Xiaohongshu (RedNote) for informal language learning. [Manuscript in preparation].

Marino, S. (2024). Refugees’ storytelling strategies on digital media platforms: How the Russia–Ukraine war unfolded on TikTok. Social Media + Society, 10(3), 20563051241279248. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051241279248

Marwick, A. E., & boyd, d. (2019). Understanding privacy at the margins: Introduction. International Journal of Communication, 13, 1157–1165.

Muljadi, B. (2025). Walled garden: A model for a nationalist-liberal society. Medium. https://bagusmuljadi.medium.com/walled-garden-a-model-for-a-nationalist-liberal-society-0b1b0a4d4e77

Nissenbaum, H. (2018). Respecting context to protect privacy: Why meaning matters. Science and Engineering Ethics, 24(3), 831–852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9975-5

Suzor, N. P. (2019). Who makes the rules? In Lawless: The secret rules that govern our lives (pp. 10–24). Cambridge University Press.

The American University School of International Service. (2025, January 23). National security and the TikTok ban. https://www.american.edu/sis/news/20250123-national-security-and-the-tik-tok-ban.cfm

The New York Times. (2025, March). Why TikTok is facing a U.S. ban, and what could happen next. https://www.nytimes.com/article/tiktok-ban.html

Trifiro, B. M. (2022). Breaking your boundaries: How TikTok use impacts privacy concerns among influencers. Mass Communication and Society, 26(6), 1014–1037. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2022.2149414

Variety. (2025, March). Will TikTok be banned again? As deadline nears, Trump says “I’d like to see TikTok remain alive”. https://variety.com/2025/digital/news/is-tiktok-being-banned-trump-deadline-sale-1236353914/

New South Wales Government. (2023, May). TikTok ban – Frequently asked questions. https://www.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/public%3A/2023-05/TikTok%20Ban%20-%20Frequently%20Asked%20Questions%20%282%29.pdf

Euronews. (2025, January 17). Which countries have banned TikTok and why? https://www.euronews.com/next/2025/01/17/which-countries-have-banned-tiktok-cybersecurity-data-privacy-espionage-fears

General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). (n.d.). General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) Compliance Guidelines. https://gdpr-info.eu/

MATE475. (2025, January 19). Is TikTok banned? Map of countries & states that have banned it so far [Map]. Brilliant Maps. https://brilliantmaps.com/tiktok-bans/

MATE475. (2023, April). Banning of TikTok on state government devices by U.S. state [Map]. Brilliant Maps. https://brilliantmaps.com/tiktok-bans/

ua.cc10 [@ua.cc10]. (2023, August 3). Ukraine war experience [Video]. TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/@ua.cc10/video/7475016873399094534

haleyybaylee [@haleyybaylee]. (2023, October 1). Take my data, China! [Video]. TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/@haleyybaylee/video/7459188012006608174

Wildcard Cameron. (2020, November 30). You need to know your digital rights [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WvVM61Nn1Xs

Be the first to comment