Imagine walking into a crowded room where people are shouting over each other—some sharing cat memes, others debating politics, and a few yelling slurs in the corner. Now imagine the people in charge of keeping the peace hand you a sticky note and say, “You sort it out.” That’s more or less what Meta is doing.

In early 2025, Meta rolled back several core content moderation systems across Facebook, Instagram, and Threads. Out went third-party fact-checkers. In came “Community Notes,” a crowdsourced moderation tool dressed up as democratic reform. Meta claimed that this change was made to achieve its recommitment to free expression.

But this move is more than just a policy update – it reflects a deeper transformation in digital platforms governance and accountability. Meta’s change marks a deliberate shift away from corporate responsibility, recasting content moderation as a user-driven task while the company retains structural power. The following unpacks what’s changing, why it matters, and how this governance “plot twist” reshapes the future of online discourse.

But this move is more than just a policy update – it reflects a deeper transformation in digital platforms governance and accountability. Meta’s change marks a deliberate shift away from corporate responsibility, recasting content moderation as a user-driven task while the company retains structural power. The following unpacks what’s changing, why it matters, and how this governance “plot twist” reshapes the future of online discourse.

What’s the Plot Twist? Meta’s Big Policy Shift Explained

In January 2025, Meta announced a major overhaul of its content moderation systems across Facebook, Instagram, and Threads. The most significant change was the termination of its third-party fact-checking partnerships in the United States. CEO Mark Zuckerberg defended this decision in a video posted on Facebook, claiming that fact-checkers had become “too politically biased” and have “destroyed more trust than they’ve created”, especially in the United States. The company framed the move as part of Meta’s recommitment to free expression.

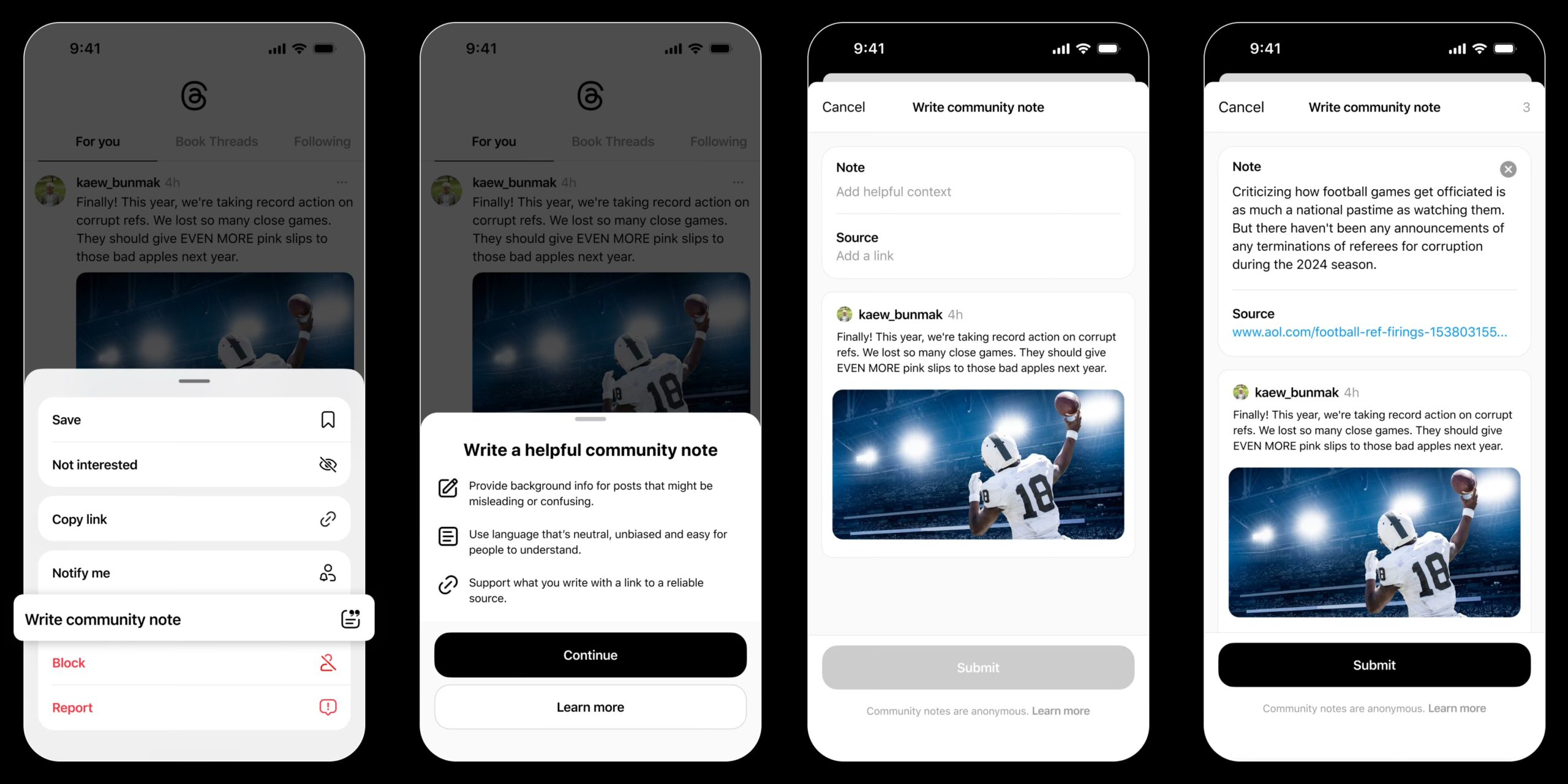

To replace the third-party fact-checking, Meta introduced a new feature called Community Notes, which is similar to the one Elon Musk implemented on X (formerly Twitter). Community Notes allows eligible users to apply to become contributors and collaboratively “add context” to posts that they consider as misleading.

Alongside this, Meta has readjusted its enforcement strategy. The automated system would now prioritise illegal and high-severity violations, such as terrorism and child sexual exploitation, while less severe violations will only be reviewed upon receiving reports (Kaplan, 2025). The company is also phasing out automatic demotions unless there is high confidence of a policy violation, and has begun relocating its trust and safety teams outside California.

Furthermore, Meta has also lifted certain restrictions on previously more strictly scrutinised topics, such as immigration and gender identity, arguing that prior rules were “too restrictive” and limited legitimate debate and discourse. Under the relaxed policies, previously removed content—such as slurs describing immigrants as “grubby, filthy pieces of shit,” calling gay people “freaks,” or labelling trans people as “mentally ill”— may now be permitted on Meta’s platforms if it does not meet the threshold for high-severity violations.

Meta explained the shift as a corrective response to the over-enforcement which resulted in too many mistakes and too much censorship. Meta positioned the moderation policy changes as part of Meta’s effort to “fix that” and return to its “fundamental commitment to free expression”. By handing moderation power to users, Meta claims it is moving towards a more transparent and community-driven model of information regulation. But is this the truth?

Community Notes in Theory vs. Practice

While Community Notes is framed by Meta as a transparent and community-driven alternative to professional fact-checking, a growing body of empirical evidence has raised serious concerns about the effectiveness of such a model. A 2024 study on the Community Notes feature on X (formerly Twitter) found no significant reduction in user engagement with misinformation, despite a notable increase in the number of created notes (Chuai et al., 2024). The researchers emphasised that corrective notes were often published too late to counter the early viral spread of misleading posts, making them largely ineffective at curbing the dissemination of misinformation during its most influential stages.

Similarly, a 2024 report by the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH) revealed that 74% of accurate Community Notes attached to misleading U.S. election posts never became visible to users, and that misleading posts often received 13 times more views than their corrective notes. The report also noted that politically divisive and polarising content—precisely the type that demands moderation—was least likely to reach the consensus threshold required for a note to appear (CCDH, 2024). These findings expose a fundamental weakness: the system is most likely to fail when it is needed most.

X’s experience has already demonstrated that although community-driven moderation may appear participatory and decentralised, its actual capacity to address misinformation remains far more limited and not better than professional fact-checking. This raises the question: why did Meta replicate a nearly identical model if it has been proven insufficient to cope with misinformation and hate speech elsewhere? Is this really a practical solution? Or is it more like a symbolic gesture masking deeper strategic motivation?

Moderation Makeover or Strategic Exit?

Meta’s shift from professional fact-checking to Community Notes is not just a technical update—it’s a strategic reorientation. From the outside, Community Notes may appear to promote user empowerment. But underneath, it serves three very practical goals: cutting costs, boosting profit, and reducing legal risk.

1. It saves money.

Ending professional fact-checking is a major cost-cutting move. Research has shown that effective moderation cannot be fully automated, so human moderators are still essential, especially for complex content like images and videos and in high-volume platforms like Facebook and Instagram (Roberts, 2019). Therefore, Meta has invested billions of dollars over the years and hired thousands of content reviewers globally to monitor sensitive content. However, it terminated its third-party fact-checking programs in the United States in January following the election of Donald Trump as president. Soon after, its moderation contractor, Telus International, laid off 2,000 workers in Barcelona – many of whom were involved in content moderation for Meta’s platforms.

It’s fair to say that Meta’s removal of professional fact-checkers and shift to community moderation is at least partly driven by financial incentives. Fact-checking is expensive, politically sensitive, and slow. Community Notes, by contrast, shifts the burden of moderation to unpaid users as free labours under the guise of “community participation.” For a platform processing billions of posts daily, that’s not just reform – it’s operational efficiency.

2. Controversy drives clicks.

The more people argue, the more ads they see. Like every other social media company, Meta thrives on engagement – and emotionally charged content tends to grab more attention than neutral, factual material. As Benkler et al. (2018) explain, social media platforms are wired to reward polarising content because it holds attention longer and encourages repeated interaction. Flew (2021) similarly notes that visibility on platforms is not neutral; it’s shaped by algorithmic logics that prioritise shareability and emotional reaction over accuracy or civic value.

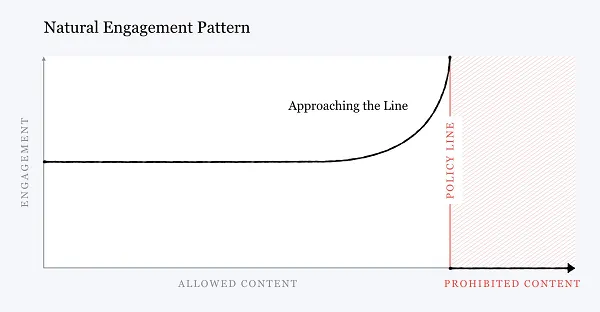

This dynamic is captured in what Zuckerberg (2021) calls the “natural engagement pattern”—a curve that shows how engagement spikes as content approaches the boundaries of what the platform allows. Posts that provoke outrage, challenge social norms, or flirt with misinformation tend to perform best. In the past, Meta used AI-driven demotion to limit the spread of this type of borderline content. But under its new policy direction, Meta has said it is “getting rid of most of these demotions” and will now act only when there’s high confidence of a violation.

By introducing Community Notes as an after-the-fact labelling tool and stepping back from proactive moderation, Meta enables more borderline content to remain visible and circulate freely. When moderation is loosened, especially around political issues, more controversial content circulates. This generates more clicks, more comments, and ultimately, more ad revenue. In this way, Community Notes serves less as a moderation tool and more as a business strategy – one that preserves Meta’s profit model while maintaining the illusion of transparency.

3. Less moderation means less liability.

The pressure on the platforms is mounting. From the EU’s Digital Services Act to the UK’s Online Safety Act, global governments are tightening the rules and expecting companies like Meta to take genuine responsibility for harmful content. In the U.S., partisan backlash and legal challenges around Section 230 have made platforms cautious about appearing too active in shaping speech. In this climate, Community Notes offers Meta a way to step back. It’s not just about policy, it’s about protection. By outsourcing moderation to users, Meta itself reduces its visibility in the enforcement decisions and thereby lowers its legal risk.

As Gillespie (2018) argues, content moderation is not a side task – it is central to what platforms do, which takes up a huge proportion of platform operation in terms of people, time, and cost. Nevertheless, all these platforms often declare themselves as passive hosts rather than active curators, who are “open, impartial, and noninterventionist” – as a way to avoid obligation or liability (Gillespie, 2018, p. 7). Community Notes perfectly fits into this playbook. It gives a sense of democracy and community-driven moderation, while allowing the platform to step back from direct intervention. If harmful content spreads uncontrollably, the error can be attributed to the lack of user consensus rather than just Meta’s negligence.

This shift matters because platforms are increasingly held accountable for their inaction. In Kenya, Meta is facing a $2.4 billion lawsuit in Kenya accusing its platform of amplifying hate speech and inciting violence in Ethiopia, leading to serious human rights violations, including the murder of a college professor. Meanwhile, in Italy, TikTok was fined $10 million in 2024 for failing to effectively police harmful self-harm content, with the regulator citing weak regulatory systems and a failure to protect users.

Given this context, by shifting to crowdsourced moderation, Meta minimises direct legal exposure by avoiding being the final decision-maker while appearing to support transparency and free expression. In this light, Meta’s withdrawal from professional content moderation is not a step towards openness but a calculated move to deflect liability, reduce scrutiny, and retain control through less obvious means.

Although legislations and regulators may eventually catch up, we all know that legal systems change slowly. By the time new rules are in place, the ripple effects of this policy shift of Meta – who owns the world’s most widely used social platforms – on global discourse, online harm, and trust in media may already be well underway, especially as the world enters another volatile political era with Trump’s comeback.

The Illusion of Neutrality: Who Governs When Platforms Step Back?

It is clear that Meta’s moderation rollback didn’t just come out of nowhere. It comes at a politically charged moment – right after the re-election of Donald Trump as president, under pressure from global legislation, and amid renewed public scrutiny of the role of big tech companies in shaping public discourse. As a recommitment to free speech, Meta’s policy shift reflects a deeper strategic reorientation: less moderation, less accountability, and less political pressure.

But the consequences go far beyond a company’s internal strategy. Indeed, as the industry leader, Meta’s announcement “marks an industry-wide retreat from the disinformation that has poisoned public discourse online.” When platforms stop actively intervening, misinformation, hate speech, extremism, and polarisation will not disappear – they will flourish. Crowdsourced moderation tools like Community Notes may provide the appearance of accountability, but as we’ve seen on X, they struggle to respond quickly, fairly, or effectively.

This is the real danger of Meta’s shift. Not just that harmful content may circulate more freely – but that the platform gets to step back while appearing to stay neutral. While the burden of moderation is passed to users, the systems that govern what we see –algorithms, recommendation mechanisms, and engagement incentives—remain firmly in Meta’s control (Benkler et al., 2018). It’s a strategic illusion: pulling back from responsibility without relinquishing control.

Therefore, Meta’s shift is not a shift towards digital democracy, but a deliberate evasion of platform responsibility. When the world’s most influential social platforms stop filtering noise, the loudest and most harmful voices often take over. The ripple effects are hard to predict, but easy to imagine: more public distrust, amplified division, and an online environment where truth and falsehoods compete on unequal terms.

The question isn’t just whether Meta will be held responsible. It’s what kind of internet we’re left with when no one is.

Reference list

Armellini, A, & Lewis, B. (Eds.). (2024, March 14). Italy regulator fines TikTok $11 million over content checks. Reuters. Retrieved April 8, 2025 from https://www.reuters.com/technology/italy-regulator-fines-tiktok-11-mln-over-inadequate-checks-harmful-content-2024-03-14/

Benkler, Y., Faris, R., & Roberts, H. (2018). Epistemic Crisis. In Network Propaganda (pp. 3-43). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190923624.003.0001

Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH) (2024). Rate Not Helpful: How X’s Community Notes System Falls Short On Misleading Election Claims. https://counterhate.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/CCDH.CommunityNotes.FINAL-30.10.pdf

Chuai, Y., Tian, H., Pröllochs, N., & Lenzini, G. (2024). Did the Roll-Out of Community Notes Reduce Engagement With Misinformation on X/Twitter? Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 8(CSCW2), 1–52. https://doi.org/10.1145/3686967

Congressional Research Service. (2021, March 17). Section 230: An overview (CRS Report No. R46751). https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46751

Department for Science, Innovation and Technology. (2023, October 26). Online Safety Act explainer. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/online-safety-act-explainer/online-safety-act-explainer

Donegan, J. (2024, April 25). It’s time to reform Section 230. ManagaEngine. https://insights.manageengine.com/digital-transformation/its-time-to-reform-section-230/

European Commission. (n.d.). Digital Services Act. Retrieved April 6, 2025, from https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/digital-services-act_en

Flew, T. (2021). Fake news, trust, and behaviour in a digital world. In Y. Ma, G. D. Rawnsley, & K. Pothong (Eds.), Research Handbook on Political Propaganda (pp. 28–40). Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781789906424.00009

Gillespie, T. (2018). All Platform Moderate. In Custodians of the Internet : Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions That Shape Social Media (pp. 1-23). Yale University Press,. https://doi.org/10.12987/9780300235029

Hutchinson, A. (2025, January 12). Everything You Need To Know About Meta’s Change in Content Rules. Social Media Today. https://www.socialmediatoday.com/news/everything-to-know-about-meta-political-content-update/737123/

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2017). Governance by algorithms: reality construction by algorithmic selection on the Internet. Media, Culture & Society, 39(2), 238–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643157

Kaplan, J. (2025, January 7). More Speech and Fewer Mistakes. Meta. https://about.fb.com/news/2025/01/meta-more-speech-fewer-mistakes/

Landauro, I. (2025, April 5). Meta’s content moderation contractor to cut 2,000 jobs in Barcelona. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/technology/metas-content-moderation-contractor-cuts-2000-jobs-barcelona-2025-04-04/

Milmo, D. (2025, April 4). Meta faces £1.8bn lawsuit over claims it inflamed violence in Ethiopia. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/apr/03/meta-faces-18bn-lawsuit-over-claims-it-inflamed-violence-in-ethiopia

Myers, S. L. (2025, January 8). Truth social. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/08/briefing/southern-california-wildfires.html

Roberts, S. T. (2019). Understanding Commercial Content Moderation. In Behind the screen : content moderation in the shadows of social media (pp. 33-72). Yale University Press. https://doi.org/10.12987/9780300245318

X Help Center. (n.d.). About Community Notes on X. Retrieved April 5, 2025, from https://help.x.com/en/using-x/community-notes

Zukerberg, M. (2025, January 7). We’re getting back to our roots around free expression [Video]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/zuck/videos/1525382954801931/

Zukerberg, M. (2021, May 6), A Bluepoint for Content Governance and Enforcement. Facebook. Retrieved April 6, 2025, from https://www.facebook.com/notes/751449002072082/

List of Figures

Figure 1. CBS News (2025). Meta platforms [Image]. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/what-is-community-notes-twitter-x-facebook-instagram/

Figure 2. Meta (2025). Testing Begins for Community Notes on Facebook, Instagram and Threads [Image]. https://about.fb.com/news/2025/03/testing-begins-community-notes-facebook-instagram-threads/

Figure 3. Facebook (2021). Natural Engagement Pattern [Image]. https://www.facebook.com/notes/751449002072082/

Figure 4. Digital Regulation Platform (2025). Regulatory governance [Image]. https://digitalregulation.org/

Be the first to comment