Have you ever noticed that every time you turn on Netflix, you’ll quickly find a show that ‘‘you want to watch’’? It’s as if Netflix knows your tastes better than you do.

That’s the ‘‘magic’’ of algorithms – or rather, that’s “manipulation”.

Netflix’s reliance on algorithms to provide personalised recommendations may seem like a way to optimise the user experience. But are these recommendations really helping us choose? Or are they controlling our choices? When you’re immersed in an infinite scroll of recommendations, are you making active decisions, or are algorithms quietly directing your attention?

What is an Algorithm?

In essence, an algorithm is a set of rules and processes that allow a machine to perform a task with the goal of solving a problem (Flew, 2021, pp. 108–110). Whether it’s a simple mathematical operation or a complex AI recommendation system, algorithms process data and generate results according to a set logic. However, algorithms are also more than mere technical tools, and carry specific business models, social norms and values.

However, algorithms can sometimes lead to privacy violations, information manipulation and discrimination. That’s why governments, tech companies and social organisations are simultaneously exploring how to better manage algorithms. Regulating the design, application and impact of algorithms like this to ensure fairness, transparency and social responsibility is known as Algorithm Governance (Danaher, 2016). Many other concepts like this have arisen with the widespread use of algorithms.

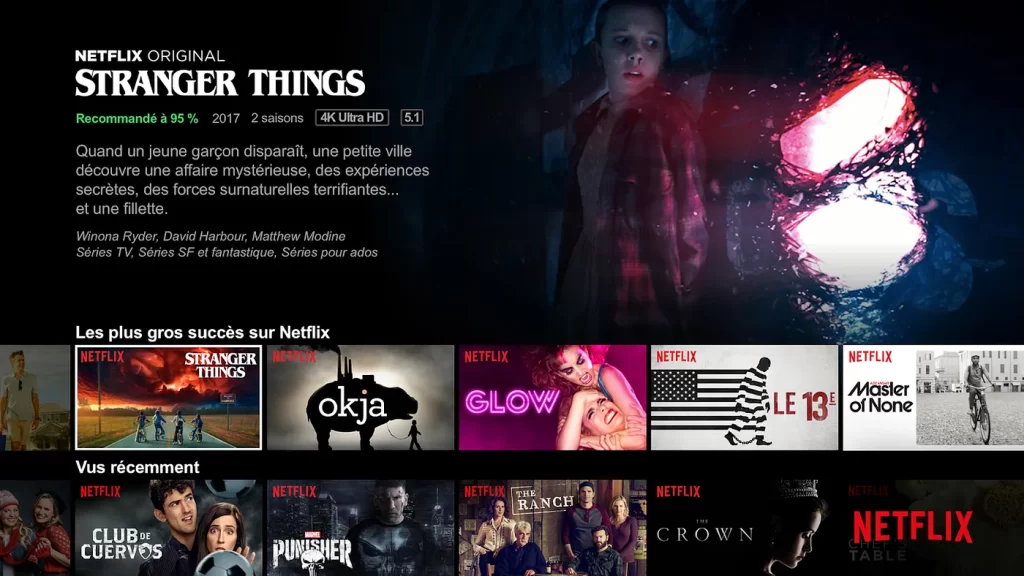

Currently, social media and streaming platforms such as Netflix, YouTube, TikTok, and others rely heavily on algorithmic recommendation systems to determine what users see. The systems precisely push personalised and tailored content based on the user’s browsing history, interest preferences and social connections. This regime has both advantages and disadvantages. While it enhances user immersion, it also poses risks such as ‘‘filter bubbles’’. It means that the user’s exposure to information is gradually limited to content that agrees with their own point of view, thus reducing their understanding of different perspectives.

How does Netflix’s Algorithm Work?

Netflix, its the world’s leading streaming platform of our time, I’m sure you’ve all heard of it. Netflix’s recommendation system analyses data such as a user’s viewing history, ratings, search history, and even the length of time they’ve watched in order to predict what they’re likely to like. Then, it guides users to choose through homepage recommendations, personalised posters and more. This not only improves the user experience using digitally driven recommendation algorithms, but also manipulates the user’s viewing preferences in an invisible way. So, back to our original question, are Netflix users’ viewing decisions free of choice or are they guided by algorithms?

First of all, it should be clear that Netflix’s recommendation system is more than a simple “guess your favourite” function, but a large and complex algorithmic ecosystem. It continuously optimises the user experience through deep machine learning and large-scale data analysis (Burroughs, 2019). Thus, Netflix achieves the purpose of maximising the viewing time and subscription retention rate of users.

Specifically, Netflix’s algorithms track our viewing habits to create a personalised “audience profile”. Netflix treats each user as an individual product. According to statistics, there are more than 100 million personalised home pages (Siles et al., 2019). It not only records which movies or episodes you have watched, but also analyses how long you stayed on each work, whether you watched it in its entirety, whether you watched a certain clip repeatedly, and even whether you paused, fast-forwarded or rewound it frequently. Additionally, Netflix’s algorithm takes into account your viewing device. The algorithm considers that mobile phone users are more inclined to watch in short bursts, while TV users prefer to spend more time watching long-form episodes in a row (Siles et al., 2019). This data not only helps Netflix predict your interests, but it also determines how the recommended list is sorted and how content is presented. For example, if you often watch horror films late at night, the system may prioritise this type of content at similar times to increase click-through rates, which is a “win-win” situation.

On this basis, Netflix has also built a huge content tagging system to deeply understand the characteristics of film and television works. Traditional film classification is usually limited to “comedy”, “science fiction”, “suspense” and other categories, while Netflix’s algorithm is more inclined to refine the labels. For example, “inspirational stories”, “female protagonists”, “dark humour” or “time travel”. This granular content analysis enables Netflix to more accurately predict user interests and provide highly personalised recommendations.

Algorithms are “manipulating” your choices

However, behind this seemingly convenient system, Netflix’s algorithms are not only passively catering to users’ interests, but are also shaping and influencing their viewing habits. Netflix claims that its recommendation algorithm is designed to optimise the user experience. But it also constitutes a system of “stealth manipulation”: what you watch, how you watch it, and even your emotional reaction to the content are all being detected.

Limitations of the Information Cocoon Effect

Netflix’s recommendation system provides users with highly personalised content recommendations. However, this personalisation system can also lead to a “Filter Bubble” effect, whereby users are long restricted to specific genres of content and have difficulty accessing other genres (Burroughs, 2019).

It’s clear that Netflix didn’t just rely on celebrity power or a director’s reputation to make House of Cards and Orange Is the New Black, but more importantly, it utilised the audience data behind its algorithms – data that helped Netflix target a “highly compatible” group of potential viewers. Its algorithms divide viewers into smaller, more refined circles of interest by analysing what they’ve watched in the past (e.g. David Fincher’s directorial style, love of political thrillers, or a focus on certain actors).

This data-based recommendation and production strategy exacerbates the “Filter Bubble” effect. In the long run, viewers are trapped in a “personalised bubble” of interests, only exposed to films and videos that overlap with their own preferences. This not only limits the diversity of content, but also makes cultural consumption on the platform more and more closed (Hallinan & Striphas, 2016). In this way, Netflix not only “adapts” content to its users, but also inadvertently “shapes” their preferences – a reflection of the information cocoon: the algorithm allows you to think you are free to choose, but in fact, you are only seeing what it wants you to see.

Cuties: The algorithm “thinks” it knows you

In Netflix, the algorithm thinks it can “manipulate” people’s thoughts and take over, but does it really know what we want?

In 2020, Netflix released a French film called Cuties. The film explores society’s growing sexualised pressure on young girls through the story of a teenage dance troupe. However, Netflix’s platform recommendation system “understood” the film in a very different way – and this misunderstanding reveals a deeper problem with algorithmic manipulation.

Netflix’s recommendation algorithm doesn’t really understand the core of the film or the user’s values. It’s based on user behavioural data and the historical behaviour of similar users. This means that a film is often recommended not because its content matches your tastes, but because the platform predicts that you are “more likely to click”. So, Netflix made a huge mistake when it chose to create a controversial cover for Cuties, instead of continuing with the original cover. The change emphasised “entertainment” and “visual impact” rather than the film’s original critical intent.

Behind this “cover manipulation” is the algorithm’s over-interpretation of user behaviour: if you like dancing, youth, or women, the system may put Cuties on your recommendation list. But it doesn’t realise that such covers can cause misunderstandings and even cause offence on an ethical level. So it led many users to reflect that the film appeared in the homepage recommendation of teenagers and children’s accounts. In this case, a petition claiming that the film “sexualises an 11-year-old for the viewing pleasure of paedophiles” collected 25,000 signatures in less than 24 hours (BBC News, 2020). The Cuties incident eventually led to worldwide protests and unsubscriptions from Netflix, as well as political attention to legislation on algorithmic recommendation systems. Netflix is forced to change the cover of the film and issue a public apology, admitting that its marketing material “misled the audience and did not represent the film as it is meant to be seen”. This also reflects the fact that algorithms don’t always “know you’’.

Taking Movie-Watching Choices into Your Own Hands

With Netflix’s powerful algorithmic recommendations, it can be difficult to make our own choices. But does that mean we’re completely powerless against algorithmic manipulation? Not really. Here are some ways to help you manage your viewing experience more proactively:

Proactively search and explore the unknown

Not all good content appears in the recommended list. You can proactively use Netflix’s search feature to search for directors, actors, or films on a particular subject that interests you. In this way, you can go beyond the platform’s recommendation logic and discover great films that may have been overlooked.

Regularly clearing your viewing history gives the algorithm a chance to “reset” itself

Netflix’s recommendation algorithm is based on past viewing history. If you’ve always watched a certain type of film, the algorithm will assume you like it and keep recommending films with similar content. If you want to think outside of this fixed framework, then regularly clearing your viewing history is an effective way to do so. This way, the algorithm will not be able to rely on old viewing history. The recommendation list will also no longer be dominated by a single type of content, but will revisit preferences.

Focus on external film reviews to broaden horizons

Why rely solely on Netflix’s own recommendation system? External platforms such as IMDb, Douban, or some professional film review websites are good choices. You’ll find more suggestions and recommendations from these platforms to help you make more comprehensive choices.

Conclusion

Netflix’s recommendation algorithm has certainly changed our relationship with movie and television content. It has made choosing easier and more efficient. From a user experience perspective, this is a huge innovation. But at the same time, we have to face the reality that, guided by algorithms, our choices are becoming more and more like “being chosen”. The essential goal of algorithms is to make users stay longer, see more, and renew faster. In this way, users think they are free to choose. But in reality, it is the algorithm based on historical behaviour, similar users, and data profiles constantly “guess” what we should see, and let us accept.

Certainly, algorithms are not necessarily bad. Personalisation itself is an upgrade in experience. But the question is, are we aware of the mechanisms that shape our behaviour? Are we capable of, and conscious of, actively stepping out of this systematic recommendation cycle? So the next time you turn on Netflix, swipe through the homepage, and click on a film that seems to be “just right” for you, stop for a second. Pause for a moment – is this really what you want to watch, or does the platform know you’re going to watch it? We may not be completely free from the influence of algorithms, but we can choose not to be completely influenced by them.

References

BBC News. (2020, August 21). Cuties: Netflix apologises for promotional poster after controversy. https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-53846419

Burroughs, B. (2019). House of Netflix: Streaming media and digital lore. Popular Communication, 17(1), 1-17.

Danaher, J. (2016). The threat of algocracy: Reality, resistance and accommodation. Philosophy & Technology, 29(3), 245–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-015-0211-1

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms (pp. 108–110). Polity Press.

Hallinan, B., & Striphas, T. (2016). Recommended for you: The Netflix Prize and the production of algorithmic culture. New Media & Society, 18(1), 117-137.

Siles, I., Espinoza-Rojas, J., Naranjo, A., & Tristán, M. F. (2019). The mutual domestication of users and algorithmic recommendations on Netflix. Communication, Culture & Critique, 12(4), 499-518.

Tom, G. (2020). ‘Cuties’ Director Says She Received Death Threats After Netflix Poster Backlash; Ted Sarandos Called Her To Apologize. Deadline. https://deadline.com/2020/09/cuties-director-death-threats-netflix-poster-backlash-ted-sarandos-called-apologize-1234569783/

Be the first to comment