Are you swiping a short video just because it stayed a few more seconds — swiping the short video again and finding that it was pushing the same type of short video that you stayed on for a long time? Or have you ever discussed a product with a friend, such as a blind box—a few minutes later, you open the social media app again and the ad for that product appear? Or maybe you just searched for a few cooking videos on Rednote, and suddenly found that the homepage is full of videos that teach you how to cook? It can feel amazing, and it even gives the impression that someone is monitoring or eavesdropping on your daily conversations. But who’s manipulating this precise creepy content? The answer is a powerful algorithmic, automated, and data-driven system.

With the development of technology, social media platforms have become an important platform for people to communicate and obtain information, which has greatly improved people’s lives. Shopping, work, and entertainment can all be done through social media platforms in one place. In today’s digital world, every time you click, pause, swipe, or even browse that video will be tracked. This data is processed by algorithmic recommender systems, and algorithm selection on the Internet refers to ‘the process that assigns (contextualized) relevance to information elements of a data set by an automated, statistical assessment of discretely generated data signals (Flew, 2021). Platforms like TikTok, Rednote, and YouTube not only use this system to provide you with the content you want to watch, but also shape your experience, changing it based on your preferences to keep you engaged.

Every day, what people do, their preferences and personal information on social media are all recorded. Big data analytics has opened up, that is, inferring future behavior of individuals and groups from past patterns of online behavior (Flew, 2021). Think about whether algorithms are helping us to make our digital lives more convenient and personalized by recommending what we want, or are they quietly controlling what we see, think, and do?

How Algorithms Affect Our Lives

In the digital age, everything we do online is converted into data. Our clicks, swiping behavior, dwell time, and even what search engine inputs are all converted into data. This data is processed by an algorithm, which is a set of processes that assign relevance to the information elements of a dataset through automatic statistical evaluation of the data signals generated in the dispersion (Humphry, 2025). This data can be turned into a profitable prediction product by some companies, which leads to the commodification of the data, which is called ‘surveillance capitalism’. It refers to the collection of user data, including behavior and social interactions, for in-depth analysis to predict and influence user behavior, predict what users will do now, soon, and in the future, and then trade this new data to maximize the business benefit of this data (Zuboff, 2019).

Algorithmic recommendation systems are ubiquitous: social media platforms, e-commerce sites, news, and TV show sites. Once this data is collected, algorithmic automation systems use the resulting data to recommend what they think the user wants to watch next. As with platforms like TikTok and Rednote, you don’t need to search at all to deduce what you prefer. For example, if I stay on an idol video for a long time or watch it several times, the algorithm may infer that I’m interested in the idol and recommend more videos about the idol, even if I don’t click the like or collection.

Over time, this algorithmic automation creates a feedback loop, meaning that the more you participate and keep engagement, the more similar the content you receive, so that what started as convenience may be quietly evolving into influence. You’ve consistently received recommendations for that content, leading you into thinking that it knows a lot about what you want to see. The algorithms tries to get people addicted rather than giving them what they really want (Smith, 2021). Disturbingly, these systems operate in such a mystery, no one knows how they work, and there is a lack of transparency. As algorithms become more powerful, the line between ‘what I want’ and ‘what the algorithm wants me to want’ is becoming more blurred.

Case 1 — ‘TikTok’ is a social media platform that ‘knows you best’

https://www.socialchamp.com/blog/tiktok-for-you-page/

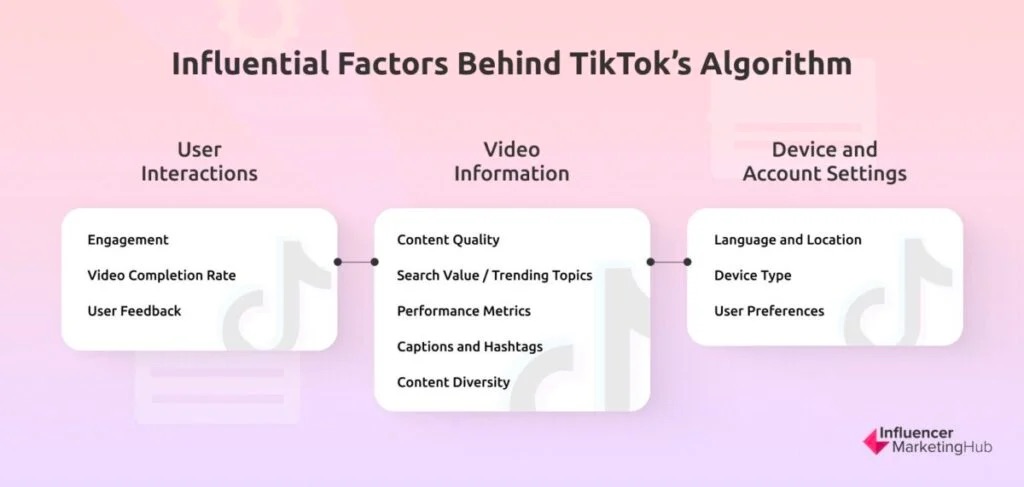

TikTok is a beloved app, and the company’s acclaimed “For You Page” (FYP) and algorithm are the most powerful tools for engaging users (Hern, 2022). Rather than relying on traditional likes, comments, and shares, its algorithm also includes the user’s watch time, swipe speed, and even the possibility of picking up some potential audio via microphone access. The company said in 2020:”Recommendations are based on a number of factors, including thing like user interactions such as the videos you like or share, accounts you follow, comments you post, and the content you create; Video information, which may include details such as captions, sounds, and hashtags; [and] device and account settings, such as your language preference, country settings, and device type” (Hern, 2022). This shift from user-led interaction to passive behavioral speculation has made data ethics and algorithmic control a pressing issue.

https://influencermarketinghub.com/tiktok-algorithm/

In a casual chat with a friend on weekdays, I mentioned the topic of “I graduated and want to buy flowers”, and when I opened TikTok again, I saw the live broadcast room selling flowers, which was very creepy, I just mentioned it in the conversation with my friend, but I didn’t search for it. This has been reported by many other users, which has led to speculation as to whether the app is listening in on conversations. In 2023, the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) launched an investigation into TikTok’s collection of personal data, and Liberal Senator James Paterson said that this behavior was particularly worrying because TikTok is subject to the Chinese Communist Party and must share information with Chinese government intelligence agencies under the Chinese intelligence law (Remeikis, 2023). TikTok’s representative said that the pixel tools used by the company are voluntary for customers to use, are industry-wide tools used to improve the effectiveness of advertising services and comply with all current Australian privacy laws and regulations (Remeikis, 2023). This touches on broader issues of digital sovereignty and user privacy, and users often don’t read long, jargon, privacy agreements, and usually just click to agree.

From a political point of view, in this mode of control, human decision-making is increasingly intervened, influenced, or even replaced by data. TikTok doesn’t just reflect the user’s interests, it also builds those interests, often in ways that the user can’t see. This also has the question: do users really ‘choose’ what they see? Or is their preference preset by an algorithm that wants them to see this? TikTok itself is an endlessly swiping, high-speed content and emotionally stimulating short video software that trains users to a specific consumption pattern, and users blindly swipe through the content on the screen. This means that what started as ‘interest-based’ viewing quickly becomes a cycle of habitual, which leads to a weakening of autonomy.

Case 2 — ‘Rednote’ When lifestyle becomes an algorithm

Rednote, also known as ‘little red book’, is one of the most influential lifestyle platforms in China in recent years, and the next ‘TikTok’ chosen by ‘TikTok refugees’ in the United States after TikTok is banned in 2025. Founded in 2013, the platform is a seamless blend of content creation, social interaction and e-commerce for urban women aged 18-35 to provide a space for them to discover and shop for overseas luxury goods, share shopping tips and exchange lifestyle stories (Vizologi, n.d.). At the core of its popularity is its powerful algorithm, which pushes original content from other users based on their personal preferences. Rednote is unique in that it can seamlessly combine personal content and commercial interests, turning users’ attention into data and purchasing power. For example, a product mentioned in the video may show at the bottom of the video, and if the user likes the product, they can click directly to buy it. Now, most people like to ‘recommend’ products or look for real-world experiences on Rednote.

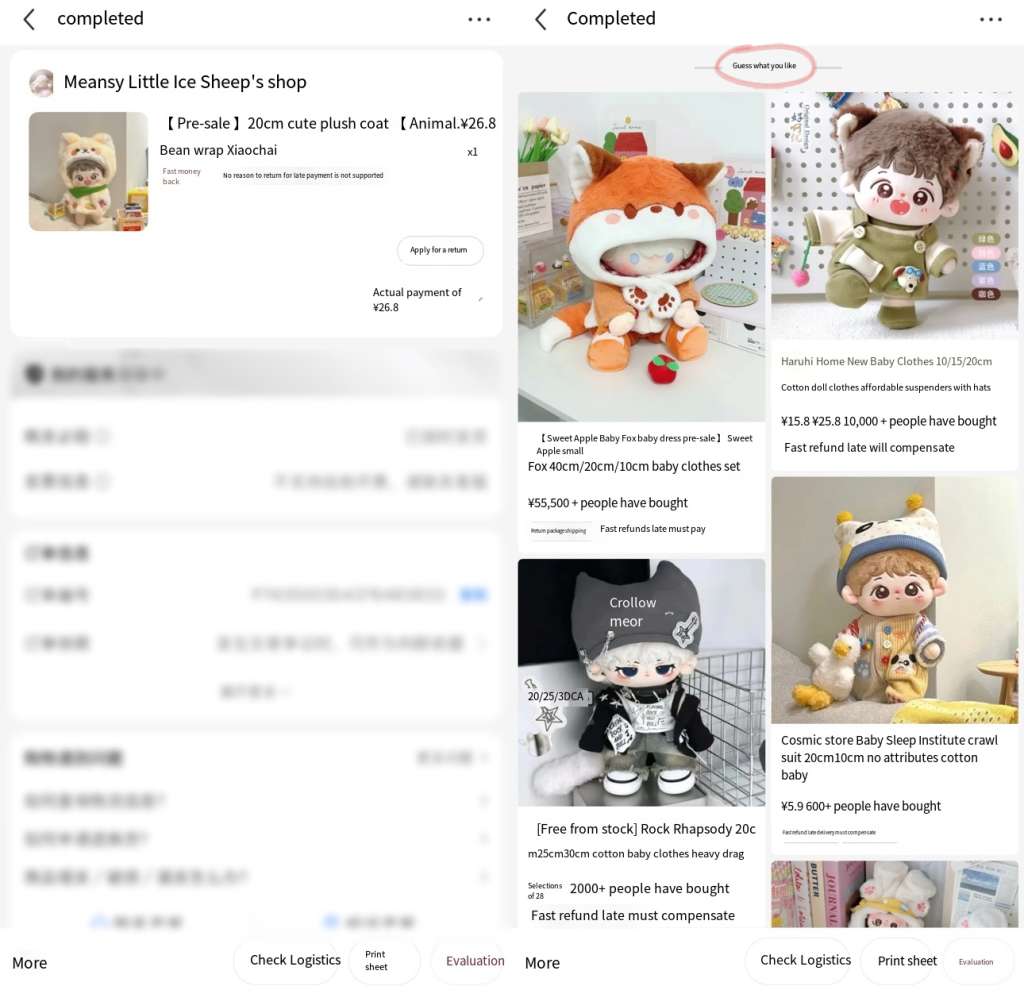

The platform uses data-based technology to detect users’ searching, staying, commenting, and sharing behaviors. Based on these behaviors, the algorithm will reasonably deduce various contents such as fashion items and product reviews that you may be interested in. It not only reflects the user’s interests, but also easily guides the user to find what they are looking for and make additional or purchases. Rednote’s algorithm pushes premium content to users, creating a triple-win situation: users can enjoy good content; Businesses can reach their target audience; Rednote maintains its reputation as a leading lifestyle social commerce platform (Hau, 2025). For example, if a user searches for ‘moisturizing skincare products’, they can provide the user with a skincare brand that is suitable for the product or what other people really experience. However, due to the sheer number of posts sent by users, it can be difficult to identify reviews disguised as genuine users of the product, rather than ‘online water army’ from businesses. Due to the lack of clear labeling, users are unable to distinguish between authentic and sponsored content, as Zuboff (2019) mention that the way surveillance capitalism works, converting data on human behavior into free raw material for the benefit of it. Users often think that they are freely exploring lifestyle patterns, but in fact, the platform’s algorithms are quietly guiding them towards consumption patterns. A lot of times, when I buy an item on Rednote, there will be a ‘Guess What You Like’ section at the bottom of the order, which basically matches the type of item I just purchased and will cause me to make another purchase. Under the guise of creating personalization for users, the desires of users are shaped. After owning one product, you are attracted to another style and buy it again, in this case, it is not “what do I want” but it’s control to “I want this?”

Screenshot By Yinghui Liu

How should we respond? Leading the future of algorithms

As algorithms become more sophisticated, our relationship with digital platforms requires us to act on our own. The question is no longer whether social media platforms such as Rednote and TikTok influence users’ behavior, which they obviously do, but rather that users need to regain a degree of autonomy on their own.

For users: First digital literacy is important. Users need to understand that ‘personalized’ content is not purely a reflection of users’ interests but is the product of using users’ ‘behavioral surplus’ as ‘raw materials’ to predict, which helps users choose more rationally what they consume and share. Users can also use their settings for a more targeted media experience, such as viewing app permissions, adjusting notification settings, and more.

For platforms: Platforms need to be more transparent, and algorithmic systems should not operate like a ‘black box’ (Pasquale, 2015). Users need to understand why they can see that content and provide real options to customize their personalization to give control back to the user. Although the algorithm meets the needs of people to swipe videos to a certain extent, the lack of transparency of the algorithm will make users feel uneasy. We need to make it clear to the user ‘why I’m seeing this?’ rather than using algorithms to guide them silently. Give users the right to view, modify, or delete their personal data, giving them more control over their data. Users are no longer passively tracked but can actively manage the use of their information by the platform.

For policy: The government needs to strengthen the regulation of digital platforms; requiring disclosure of information and ‘plain language’ formats for cosumers (Pasquale, 2015); Require tech companies to disclose the general framework of their algorithmic systems.

Conclusion

Algorithms act as invisible hands that guide us in the way of browse content and interactions. While it provides us with convenience and personalization, it also subtly controls our behavior. Therefore, we must understand that the recommendation system is not only a service to the user but also control and understand how the recommendation is generated, to take back the autonomy that belongs to us. Currently of ‘you think you like it, but actually it wants you to like’, we need to re-examine the meaning of ‘choice’. For example, is this video really what I want to see? Or is it what the algorithmic recommender system wants me to see?

Reference List

Flew, T. (2021). Issues of Concern. In T. Flew, Regulating platforms (pp. 79–86). Polity.

Humphry, J. (2025). ARIN6902 Digital Policy and Governance, lecture 5, week 5, module 5: Week 5 Issues of Concern: AI, Automation and Algorithmic Governance [PowerPoint slides]. The University of Sydney, University of Sydney Canvas. https://canvas.sydney.edu.au/courses/64614/pages/week-5-issues-of-concern-ai-automation-and-algorithmic-governance?module_item_id=2584696

Hern, A. (2022, October 24). How TikTok’s algorithm made it a success:’ It pushes the boundaries’. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/oct/23/tiktok-rise-algorithm-popularity

Hau, J. (2025, January 15). The XiaoHongShu/ REDNote Algorithm- How Does It Work?. Prizm Group. https://prizmdigital.co.nz/xiaohongshu-algorithm/

Pasquale, F. (2015). INTRODUCTION: THE NEED TO KNOW. In The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms That Control Money and Information (pp. 1–18). Harvard University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt13x0hch.3

Remeikis, A. (2023, December 28). TikTok’s data collection being scrutinised by Australia’s privacy watchdog. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/dec/28/tiktok-data-collection-inquiry-australia-privacy-watchdog-marketing-pixels

Smith, B. (2021, December 5). How TikTok Reads Your Mind. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/05/business/media/tiktok-algorithm.html

Vizologi. (n.d.) Xiaohongshu’s Company Overview. https://vizologi.com/business-strategy-canvas/xiaohongshu-business-model-canvas/

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power (First edition). PublicAffairs.

Be the first to comment