It’s not a video, it’s a “bait” from the algorithm.

Once you pick up your phone and tap TikTok, it’s hard to exit quickly?

It’s not your fault.

But have you ever had any of the following experiences?

Just casually scrolling TikTok for a while, the homepage recommendation videos are gradually filled with the same type of content: It may start with a funny pet video, then a beauty attack from a beautiful lady or a handsome guy, then a crazy tutorial of “losing 5 kilograms in a week,” and finally become an extreme statement of “a politician from a certain country inciting hatred”. At the beginning, you are so happy and relaxed by watching videos, but when you quit it, you become extremely anxious and empty.

You don’t even actively search for these topics, but the platform’s “guess what you like” is like a finely woven web to catch you. We often think that we are “choosing” what we like, but in fact, the algorithm is “choosing” us in reverse. It quietly manipulates and shapes everything we see, eventually trapping us in a digital version of “the Truman Show.”

The “mind Reading” of algorithms – How does behavior data “predict” you?

So why is the platform’s personalized recommendations so tailored to our preferences? How does the platform “see through” us? Is it the personal information we fill in when registering an account, the interest tag we choose, or the keywords in the search box that reveal us?

To better understand TikTok’s power, you need to understand its core “weapon”: the recommendation algorithm.

According to TikTok (2020), its algorithm works in three simple steps:

1. Capture behavioral signals: staying for more than 2 seconds is judged as “interest”, repeated viewing of similar videos triggers “addiction index”, and forwarding behavior is marked as “high recognition”.

2. Generate user portraits: Using machine learning to classify fragmented behavior as “tags”

3. Predictive recommendation cycle: Constantly test your reactions with new content to adjust new direction.

So, what platforms value more is actually our behavior data. Algorithms turn our every swipe, pause, and like into a calculable “Data Exhaust.” Our “casual” reactions are teaching it how to capture our attention with more precise content. Zuboff (2019) argues that digital platforms are not content with collecting data, and their real purpose is to manipulate our attention and choices by using these seemingly insignificant traces to predict our next actions.

So what you are watching on TikTok is no just videos, to some extent, it is predictions that the platform feeds you. For example, if you stay on a video for a few seconds longer, or watch similar content several times, the algorithm will make the decision: “You like this” and it will continue to increase the push weight of such content. Over time, this prediction becomes not just a record, but an active intervention – it gradually “shapes” your preferences, even your emotions and value judgments.

As Cinnamon (2017) states that, the first principle of the Big Data era is that “every actor, event, and transaction can made visible and calculable.” This behavioral data is collected in real time and fed into complex predictive models. The platform’s algorithms automatically learn which content “makes you stop more,” and then adjust the push strategy until you’re fully engaged.

The algorithm knows what you want, even before yourself realize it. Does this sound like an intimate service of technological superiority? But here’s the thing: it’s a one-way control. You can’t see how these predictions are made, and you can’t really quit it.

A Wall Street Journal experiment – How does TikTok domesticate users?

In 2021, the Wall Street Journal conducted an experiment: they signed up hundreds of TikTok “robot users” with different locations to simulate user behavior across different age groups and interests. The results show that in less than 40 minutes, the algorithm can “lock” the user’s interest based on the user’s stay time and viewing behavior, and begin to push relevant content. And over time, the recommended content gradually focuses on a specific topic, forming an “information cocoon.” For example, some accounts were pushed a large number of videos related to negative emotions such as anxiety and eating disorders in a short period of time, suggesting that the algorithm can have an impact on users’ mood and behavior.

The core of this algorithmic mechanism is that the “longer” you look at means “you want to look” and “you are interested”, and the platform uses this as a basis to predict, reinforce, and re-recommend. This closed loop of “behavioral feedback – algorithmic judgment – content weighting – behavioral feedback” is one of the reasons why we are trapped in the “algorithm cocoon”. Social platforms seem to give us the right to browse “freely”, but it does not actually serve user needs, but seeks to “maximize engagement”.

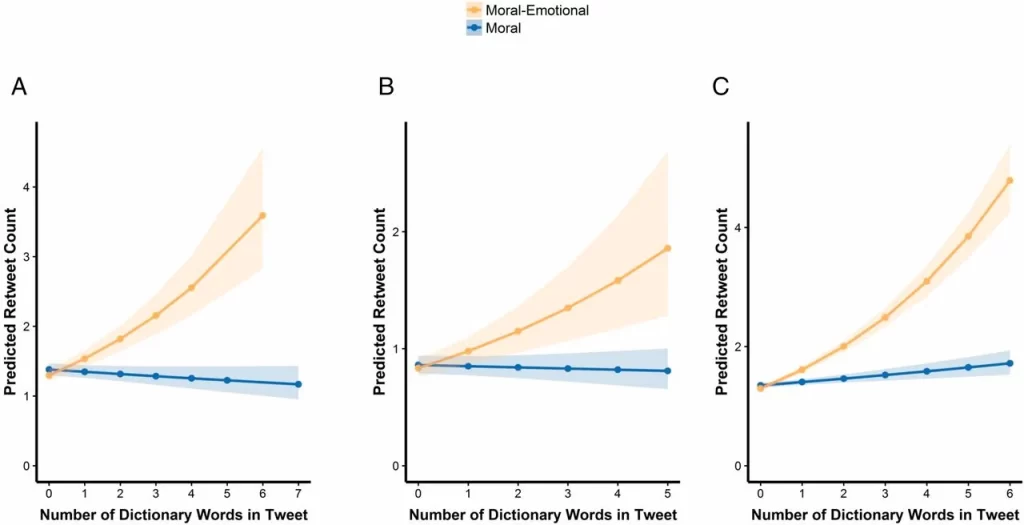

According to related researchers (2017), different types of emotions (such as anger and sympathy) have different degrees of influence on the spread of content. However, content that included emotion words had significantly higher sharing rates than content that did not. Such emotional content is more likely to spread among homogenous groups, which may exacerbate the echo chamber effect of information and social polarization.

What is more frightening is that it seems that our “preferences” are satisfied, but in fact, the “purpose” of the platform is thus realized: make you stay longer and interact more frequently, while the platform expands user stickiness and helps improve its advertising efficiency and business value.

Monitoring Capitalism – How does Your anxiety nourish the platform?

In TIKTOK’s seemingly neutral recommendation algorithm model, we are no longer users, but objects to be trained. According to the “surveillance capitalism” proposed by Zuboff: digital platforms not only collect data on human behavior, but also use that data to build predictive models that turn our future behavior into predictive commodities that can be traded. These platforms take human experience as raw material, turn it into behavioral data that is processed by machine intelligence into predictive products that are ultimately used to guide or even manipulate user behavior.

For example, when you watch a fitness video, it is no accident that the algorithm pushes a mixed “body shaming” video. It first start with creating anxiety: it shows you the “perfect body” and triggers feelings of self-deprecation. Then offer the “antidote”: recommended fitness classes, ads for meal replacements, promises of “rapid transformation.” Finally, the end is closed-loop harvesting: your clicks and purchases are recorded and become evidence to charge advertisers. TikTok doesn’t just collect your data, it sells you to fitness brands as a “commodity” – the more anxious you are, the higher the advertising conversion rate. This is the chain of exploitation that monitors capitalism: human experience → behavioral data → predictive products → profits. Platforms even don’t need to know who you are, they can use algorithms to predict your next move and sell that certainty to advertisers, politicians and even criminal groups.

Platforms serve as middlemen, they specialize in shifting alliances, sometimes advancing the interests of customers, sometimes suppliers: but all to create an online world that maximizes their own profits.

Just as the “dataism” and “dataveillance” proposed by Dijck (2014) further reveal this trend: Under the techno-utopian discourse, the platform claims that “data can tell the truth” and uses algorithms to pursue “optimal efficiency”, but in fact, users’ identities, preferences and emotions are “labeled”, and algorithms continue to impose behavioral guidance according to these labels, while users are neither visible nor able to resist these processes. In other words, the algorithm is not serving us, it is managing us. We, on the other hand, thought we were “streaming short videos.”

Serious effects – How do we go from “data slave” to “sober user”?

What is more serious: The consequences of algorithmic recommendations go far beyond that. Recommendations built from behavioral data are actually reshaping our emotional experiences, cognitive boundaries, and even the way we perceive “reality.”

For individuals, the most immediate impact is on mental health. Topics such as “perfect body”, “extreme dieting” or “fear of failure” can exacerbate anxiety, body shame and self-doubt. The Wall Street Journal experiment proved that TikTok can still “funnel” users into this stream of emotional, highly sensitive content without actively searching.

From the social level, this mechanism of “targeted push” and “emotional amplification” is quietly exacerbating what we call the filter bubbles effect: users are exposed to more and more single and extreme information, and it is difficult to see different views, which ultimately leads to the shrinking of public consensus space.

American scholar Pasquale (2015) also points out that when algorithmic decision-making becomes a “black box”, it is not transparent and uncontrollable. We don’t know how the algorithm judges our interest, nor can we “jump” off the recommended route it has set. Without the right to know and to choose, our “what we know and feel” gradually ceases to belong to us.

In order to break the algorithmic cage, multiple parties are needed:

As a user, you need to train “data literacy” as soon as possible: realize that every swipe is training the algorithm, and actively like “disinterested” content to break the information cocoon. The counter-tools can be helpful to make a difference, such as installing plug-ins to limit data collection. Also, the screen time keeps us alert and reduces app usage.

It is not enough to rely on the platform to consciously optimize the algorithm mechanism, but also need the government’s supporting policies to restrict them. For example, the EU’s Digital Services Act requires platforms to be more transparent about algorithms and online advertising. In addition, in order to break the monopoly of the tech giants, non-profit open source algorithms should be funded by the government.

Last but not least, we truly need more themed activities in society, such as setting a weekly “no algorithm day” and returning to in-depth information acquisition methods such as books and offline conversations.

Conclusion:

We think we are just scrolling through short videos, but we are actually being filtered by algorithms. TikTok shows not just what you want to watch, but what the platform has calculated from behavioral data to “stimulate you the most” – anxiety, desire, anger, the more extreme, the more effective. We are constantly fed, not reality, but a “computerised world” that can be predicted and translated into clicks and profits.

This is not the result of technological neutrality, but a top-down logic of control: platforms control the flow of information, and the flow of information controls what we see, which in turn affects what we believe and feel. This is the essence of surveillance capitalism.

TikTok traps us in an information cocoon, gradually depriving us of initiative in a mechanical cycle of prediction-feedback. The simplest thing we can do is to press pause before each swipe and reconfirm “Who I am” and “What I want.”

References:

Brady, W. J., Wills, J. A., Jost, J. T., Tucker, J. A., & Van Bavel, J. J. (2017). Emotion shapes the diffusion of moralized content in social networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences – PNAS, 114(28), 7313–7318. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1618923114

Cinnamon, J. (2017). Social injustice in surveillance capitalism. Surveillance & Society, 15(5), 609–625. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v15i5.6433

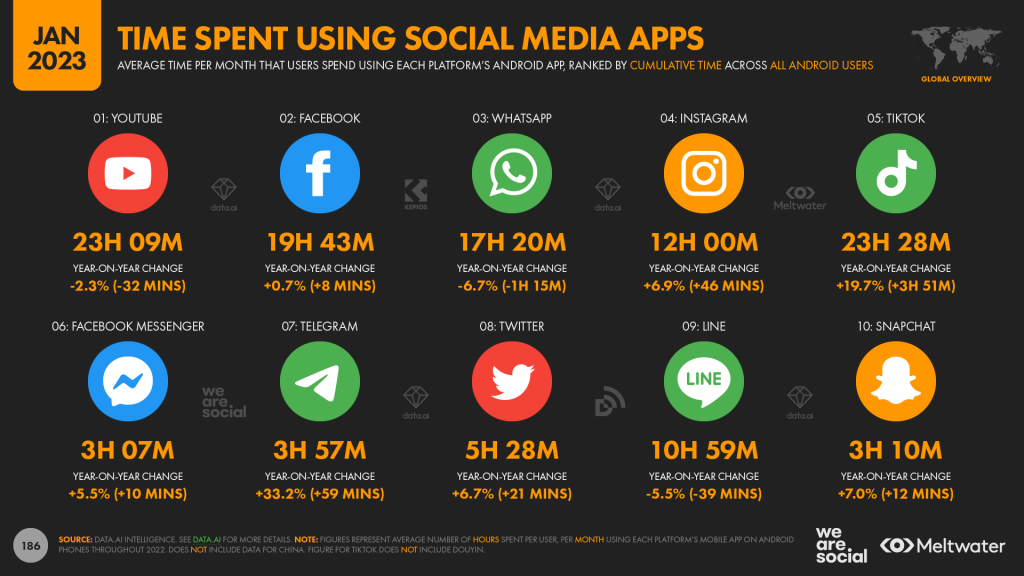

DataReportal. (2023). Digital 2023 Global Overview Report. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-global-overview-report

Pasquale, F. (2015). The black box society : the secret algorithms that control money and information. Harvard University Press.

The Wall Street Journal. (2021, July 21). How TikTok’s algorithm figures you out [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nfczi2cI6Cs

TikTok. (2020, June 18). How TikTok recommends videos #ForYou. TikTok Newsroom. https://newsroom.tiktok.com/en-us/how-tiktok-recommends-videos-for-you

Van Dijck, J. (2014). Datafication, dataism and dataveillance: Big data between scientific paradigm and ideology. Surveillance & Society, 12(2), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v12i2.4776

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism : the fight for a human future at the new frontier of power /. PublicAffairs,.

Be the first to comment