Nowadays, most apps we use will request your data even if you don’t say “yes”, such as turning on data privacy settings by default. From the moment you open the app, you are tracked. You have never said “I agree”, but the platform has assumed you “agree”. This default setting behind “silence” is becoming one of the most common, gentlest, and most terrifying ways of privacy violation in the digital platform era. It is not as sensational as a leak, but it quietly takes away your data, your preferences, your location, and even part of your life.

In today’s digital platforms, silence is no longer neutral, default settings turn user inaction into consent, quietly stripping away privacy rights.

Silent consent is a new system of soft control over personal data.

What is “consent” supposed to be, but what does the platform turn it into?

“Consent” means you understand what’s happening and you say “yes” to it. But today, that’s not how it works. Terry Flew (2021) explains that big platforms design their apps to look like you have a choice — but in fact, you can’t use many features unless you agree. Sometimes, just using the app means you “agree”. It’s not really your choice. It’s their system, and you are just trying to use the service. You never said “yes” to tracking, but the app thinks you did, because you didn’t say “no”.

The rules are hidden from us, In Lawless, Nicolas Suzor (2019) said that the platform sets a set of “invisible rules”. You are not “negotiating use” with the platform, you are acting within the rules of the game that the platform has already written. This is the biggest danger of “silent consent”. You think you have done nothing, but in fact you have been “authorized”. When the users being silent, the platform assumes that you have agreed by default, so data begins to be collected, location is continuously turned on, clipboard is continuously read, behavior is analyzed, but you are completely unaware and have no control.

The Case: Temu and Silent Data

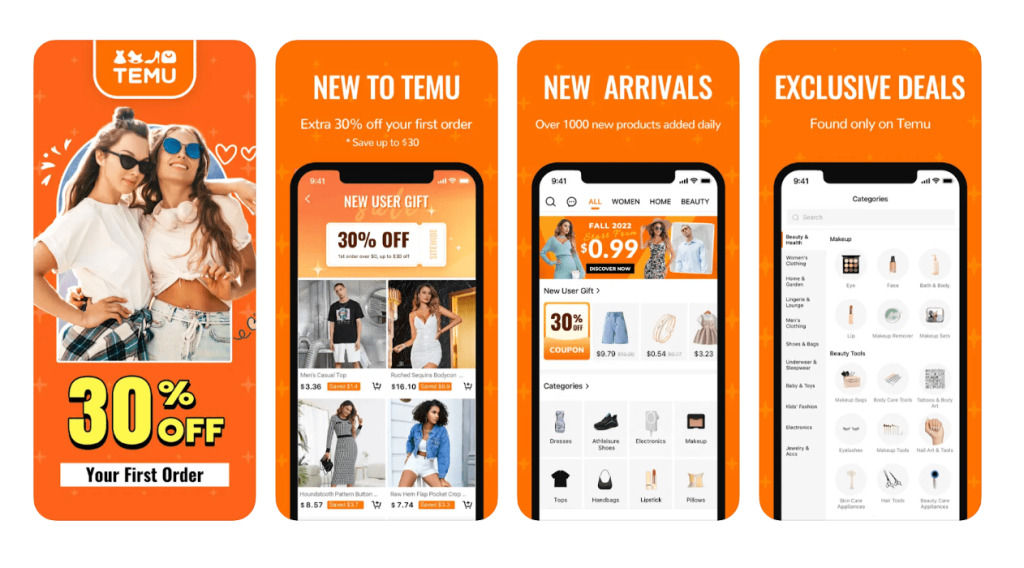

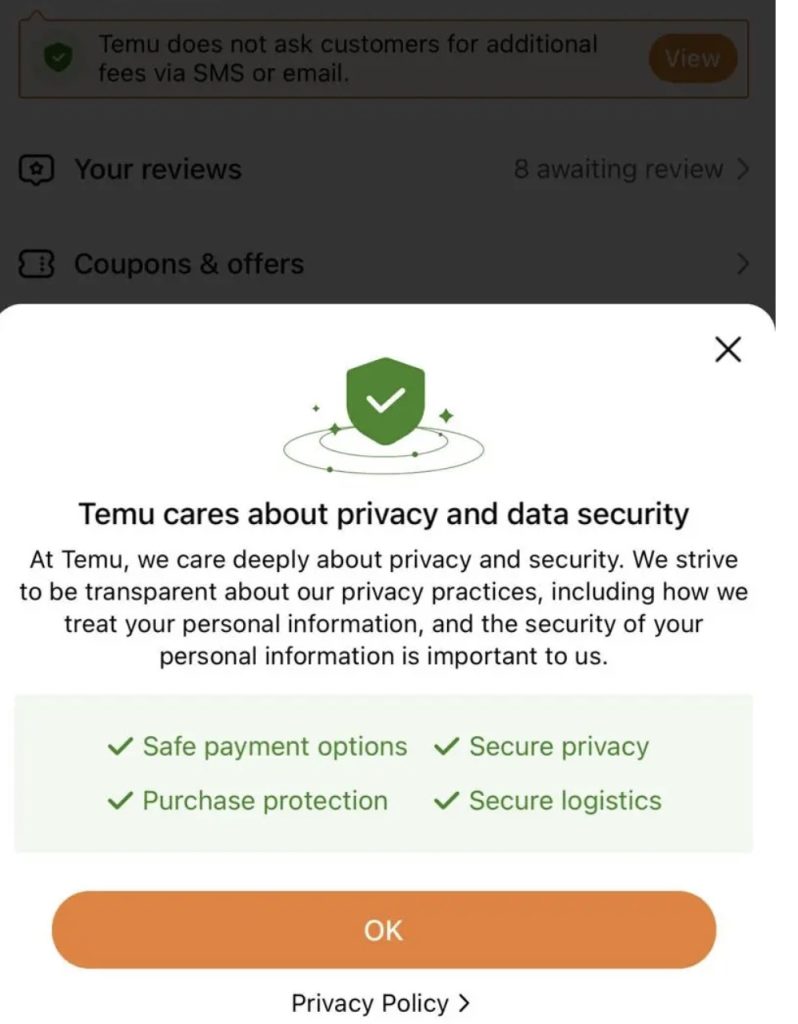

Temu is a shopping app worldwide in 2024. People liked using Temu because everything is cheap, the app is fun to use, and items are delivered quickly. However, by 2025, more and more people began to worry about what’s happening behind the screen. Temu was found to be collecting a lot of user data and many users didn’t even know it was happening. Temu collects information like your real-time location, your phone type, how you use the app, and even the content you copy on their phone. It also asks for permissions to access data from other apps. What is important to note is that most of these data permissions are turned on by default. When users install the app, they are rarely shown a clear message about what data is being collected. The app’s privacy policy is very long and hard to understand. It’s full of technical words, and very few users will read it all.

In early 2025, the South Korean government opened an official investigation into Temu’s privacy practices. Authorities said the app might collect personal information without proper consent. Around the same time, in the United States, people filed class-action lawsuits against Temu, they said the app used dark patterns to trick users into giving up data, such as hiding the “reject” button or making users believe they had no choice. These issues were not only shared on social media but also reported by trusted news outlets likeWorld Journal and Aju Daily. So, it’s a real concern that many people are now aware of.

What Temu shows us is how silent consent works in everyday life. Most users click “yes” because it’s the only way to use the app. Others don’t click anything at all but still end up sharing personal data just by opening the app. The app’s design is made in a way where doing nothing means saying yes, that’s the problem. This kind of design doesn’t look dangerous at first. But it quietly takes away people’s privacy, bit by bit. It makes people think they have a choice, when actually, the choice is already made for them. This is why silent consent is not harmless; it is a soft and quiet way to take control of user data without real consent.

When ‘Choice’ Is Designed, and Understanding Is Out of Reach

“Choice” is just the surface, the real control is hidden in the system

On most digital platforms, users are told that they have a choice. There are usually two buttons: “accept” and “decline.” It looks simple, but in practice, this choice is often not real. If you decline, you may be locked out of the service entirely. Whether it’s a shopping app, a news website, or a social media platform, clicking “no” can mean you don’t get access at all. That creates pressure—pressure that is built into the design of the system. These interfaces are not neutral. They are carefully created to guide behavior, and often to push users toward accepting. Design choices such as dark patterns, pop-up urgency, or only showing the “accept” button upfront are ways platforms influence user behavior while appearing to offer freedom. Many users, especially those in a hurry, will click “accept” without even thinking, it’s because they feel they don’t really have a better option.

But what makes this system even more concerning is that most users don’t actually know what they’re agreeing to in the first place.

Real control lies with those who hold the information

We should click “agree” after real understanding of the terms, however, in practice, digital platforms often ask users to make decisions without understanding what’s at stake. Privacy policies are usually long, filled with legal and technical language.They are not written for the user but for the platform’s own legal protection. Most people don’t have the time, ability, or energy to read and make sense of them. It leads to a serious imbalance of information between the platform and the users. Platforms know exactly what data they collect, where it goes, how long it is stored, and who it is shared or sold to. Users, in contrast, know almost nothing. If someone clicks “agree” without knowing what they’re agreeing to, can we really call that meaningful consent? This inequality in knowledge is not accidental—it is part of how these systems are designed. Many platforms collect data when people are confused, tired, or simply not noticing what’s going on because that’s when it’s easiest to collect their data without getting in the way. Over time, this becomes normal. It becomes accepted. If a user doesn’t fully understand or is simply too exhausted to read the policy, the system still treats that as permission. But this isn’t harmless, it’s a form of structural exploitation. When this kind of information gap becomes the default, we shouldn’t only talk about “improving design.” We need to ask a harder question: Who gets to define what consent really means?

When Privacy Becomes a Setting Instead of a Right

Privacy, as a basic right, should be something people have automatically. It should not be something they have to search for through hidden menus or change through complicated settings. On many digital platforms today, privacy has turned into an opt-out system. It only works if users know what to do and act quickly. If not, their data is collected by default, often without them even realizing it. When saying no to data sharing means losing access to a service, or when turning off tracking requires going through several confusing steps, privacy stops being a right. It turns into a kind of privilege that platforms control. Not everyone has the same ability to manage that. Older people, those who are not fluent in the platform’s language, or users who are not familiar with technology are more likely to be affected. They are not less concerned about privacy, but the system is simply not built with them in mind (van Dijck et al., 2018).

Changing how privacy works is not just about design. It reflects a deeper issue about how platforms are governed. As Bennett and Lyon (2008) point out, many systems today rely on passive data collection. If the user does nothing, the system will still collect their data and treat it as consent. Companies no longer need to build real trust. They just use people’s silence to get what they want. Over time, this “silent” process causes people to unknowingly lose control of their digital lives.

A truly fair system should be built around the rights of the user

If we want to solve the problem of digital consent, we cannot simply make some superficial changes to the interface. Making the “Agree” button more visually appealing or shortening the privacy policy may help, this does not solve the root of the problem. We need to focus on questions like, Who makes the rules? Who controls the data? Who decides that silence is consent? A truly fair system should be built around the rights of the user. Before collecting their data, platforms should explain what they are doing in simple language, give users clear options to refuse, and allow them to change their minds later. It shouldn’t be that the moment you open an app or website, it automatically assumes you’re ready to share everything. And of course, this can’t be left up to platform goodwill. It requires legal intervention. The law needs to make it clear that consent should be given knowingly, be reversible, and never be forced. Silence should never be construed as permission. No user should lose access and be penalized for choosing to protect their privacy.

Conclusion

In the digital world we live in, most of us have clicked “agree” without reading the fine print. We scroll past long privacy policies, skip over permissions, and move quickly just to get to what we want. But behind those quiet clicks lies a much bigger problem—one that affects not just individuals, but the shape of digital rights in society. Throughout this blog, I’ve argued that silent consent is not real consent. When users don’t truly understand what they’re agreeing to, or when they have no meaningful way to say no, then that consent is meaningless. However, many platforms still operate under systems where silence, inaction, or confusion are treated as consent. These systems are not designed by accident. They reflect how power functions in digital spaces: platforms set the rules, control the flow of data, shift responsibility onto users, and benefit from this structure.

What makes this worse is that the people who are most vulnerable, those with less digital literacy, less time, or fewer resources, they are often the ones with the least control. In these systems, privacy is no longer a basic right, but something you have to dig for, it is only accessible to those who know exactly where to go and what to do. We need to rethink what “consent” means in the platform era. It should happen with the user’s full understanding and should be supported by law to protect users from having to choose between access and autonomy. And it should be backed by laws that protect users from having to choose between access and autonomy. Silence should never be the price of participation.

References:

Aju Daily. (2025, March 10). South Korea launches privacy investigation into Temu app. https://www.ajudaily.com/view/20250310-temu-privacy

Bennett, C. J., & Lyon, D. (2008). Playing the identity card: Surveillance, security and identification in global perspective (pp. 24–29). Routledge.

Bioswag. (2025, January 10). Best Free Casino Games Ios – Bioswag.https://bioswagus.com/2025/01/10/best-free-casino-games-ios

Flew, Terry (2021) Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity, pp. 72-79.

Iubenda. (n.d.). App Privacy Policy: What you Need to Know + Examples. Iubenda. https://www.iubenda.com/en/help/147125-app-privacy-policy-what-you-need-to-know-examples

Suzor, Nicolas P. 2019. ‘Who Makes the Rules?’. In Lawless: the secret rules that govern our lives. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 10-24

世界新闻网. (2024, February 17). 涉侵隐私 多州居民集体告Temu. https://www.worldjournal.com/wj/story/121275/7774064

特派員黃惠玲╱芝加哥報導. (2024, February 17). 涉侵隱私 多州居民集體告Temu. 世界新聞網. https://www.worldjournal.com/wj/story/121275/7774064

Two sides of the same coin – the right to privacy and freedom of expression. (n.d.). Privacy International. https://privacyinternational.org/blog/1111/two-sides-same-coin-right-privacy-and-freedom-expression

van Dijck, J., Poell, T., & de Waal, M. (2018). The platform society: Public values in a connective world. Oxford University Press.

Be the first to comment