Figure 1. The Prevalence of Hate Speech and Online Harms. (source)

The Free Speech Narrative: A Shield for Harm?

Free speech is often seen as the foundation of democracy. It portrays the idea that everyone deserves an equal voice so that no one will dominate a conversation. In theory, digital platforms have expanded this right by making it easier for anyone to share content and discuss their opinions in a shared space.

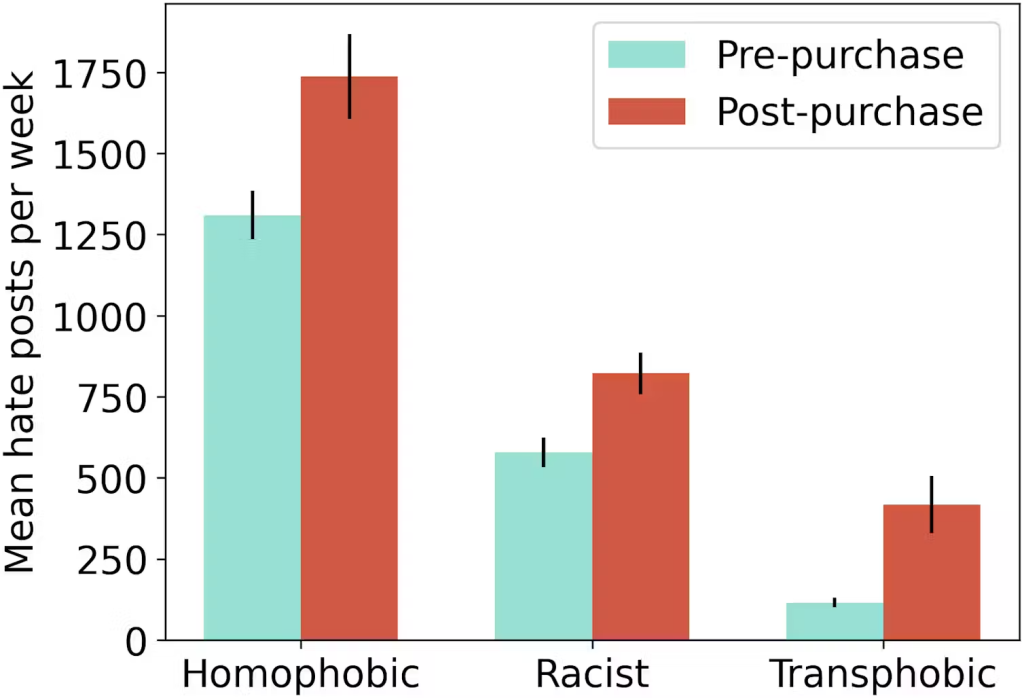

Major companies often use free speech as an excuse to defend themselves against criticism and regulatory intervention. X’s former CEO, Dick Costolo, dubbed the firm the “free speech wing of the free speech party.” After the acquisition, Elon Musk doubled down on this perspective by significantly reducing X’s moderation workforce, dismantling its trust and safety teams, withdrawing from EU co-regulatory documents, and changing X’s overall content moderation style to a more permissive approach (van de Kerkhof, 2025). This resulted in a significant increase in harmful content. Specifically, posts containing hate speech were consistently 50% higher after Musk took over X, and the engagement rate with those posts increased by 70% (Jensen, 2025). When thinking about Musk’s self-declaration as a “free speech absolutist” and the change in X’s content together, the association is concerning.

Figure 2. Mean Hate Posts per Week on X Before and After Its Acquisition by Elon Musk. (Jensen)

The real problem is not just about what is being said. It is about how platforms are designed to amplify it. With limited enforceable policies, inconsistent moderation, black-box algorithms, and design loopholes, the system itself creates the perfect conditions for online harm to thrive. If we want real change, we must stop focusing solely on content and start fixing the structures that spread it.

When does freedom of expression stop being a right — and start becoming a risk?

Finding a balance between freedom of speech and hate speech has been a recurring dilemma since the invention of the internet. As Flew (2021) notes, the platform free speech debate is far more complex than platforms portray, and platforms’ free speech absolutism needs to be considerably modified legally and regulatorily to prevent further harm. Platforms are not neutral intermediaries. Instead, they actively shape what is seen and heard through algorithmic design, content curation, and business incentives. By framing themselves as defenders of free speech, platforms strategically deflect responsibility for the harms created and amplified within their system.

Algorithmic Amplification: The Engine of Online Harm

Social media platforms use powerful machine learning to tailor content. These algorithms determine feed content using enormous data sets, which include user preferences, interaction patterns, and popular themes. Sinpeng et al. (2021) assert that algorithms represent companies’ values and ambitions. They are highly framed by social and political values embedded in institutional cultures and commercial imperatives of the platform. In most cases, the primary goal of a digital platform is to make money, which justifies the reason why virality and engagement are emphasized over objectivity and responsibility.

Contents that are rewarded for high engagement are often ones that are emotionally charged or polarizing. Unfortunately, this makes hate speech and harmful content thrive as they provoke strong reactions, even if those reactions are negative. Gibbs (2011) commented on the contagious nature of affect and proposed that affects are powerful enough to be transported from one context into another. These affects are triggered subconsciously and may lead to the formation of subjective beliefs. For instance, imagine you just had a tense interaction with your supervisor, who happens to be Asian. You open a social media app and see a post claiming that “all Asians are arrogant” or blaming them for COVID-19. The lingering frustration from your previous experience may subconsciously influence how you view the post. You might find it more believable, not because of evidence, but because your emotional state has made you more receptive. Worse, you may become a carrier for this affective bias by reposting the content or expressing similar sentiments yourself.

Do you see how online hatred can spread like a virus? With just one click, someone can launch an attack — and that click can trigger a chain reaction. The post spreads, others join in, and before long, a wave of harm has been unleashed with barely any effort at all.

Figure 3. Echo Chamber and the Society. (source)

Similar to feedback loops, the concept of an echo chamber is also worth noting. Algorithms amplify content by targeting specific audiences based on their preferences and online habits, creating an environment where people only encounter information or opinions that reflect and reinforce their views (GCF Global, 2019). Without media literacy to help you spot these issues, it is very easy to fall into the trap of platform algorithms designed to capture your attention.

Case Study: X and the Sydney Church Stabbing Video

Video 1. What’s behind the fight between Elon Musk’s X and Australia’s eSafety commissioner?

On April 15, 2024, Bishop Mar Mari Emmanuel was stabbed by a teenager during a live-streamed service at Christ the Good Shepherd Church in Wakeley, Sydney (Watson & Mao, 2024). The attacker also injured another priest and a churchgoer who tried to intervene. Fortunately, no lives were lost, and the teenager was arrested at the scene. However, the video of the attack went viral on social media, generating hundreds of thousands of views across platforms.

Immediately after, Australia’s eSafety commissioner Julie Inman Grant issued thousands of takedown requests to platforms such as Instagram, TikTok, and X in order to prevent the further spread of the stabbing video. Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, responded by adding versions of the video to its database to ensure that future attempts to upload are blocked (Taylor et al., 2024). TikTok’s spokesperson replied that they activated their longstanding procedures to manage tragic events like this within 30 minutes of the news (Taylor et al., 2024). Other social media platforms soon followed the effort to remove videos about the incident. In contrast, X turned down the takedown request, which led to a temporary legal injunction issued towards it requiring it to hide related posts until further notice.

Living up to his “free speech absolutism” stance, Elon Musk refused to follow the legal injunction in totality. He only made those videos unavailable to Australian users by geo-blocking them. In his defense, Musk repeatedly used the free speech shield and tweeted multiple times about the issue. He also argued that a country should not be allowed to censor content for all countries, as it will give certain countries the power to control the entire internet.

In the end, Australian eSafety abandoned the month-long Federal Court case with X Corp after multiple blows in court and the temporary injunction expiring. “Freedom of speech is worth finding for,” Musk posted. In a broader context, this case was seen as a test of Australia’s ability to enforce its online safety acts on social media platforms (Evans & Butler, 2024). Although Australian eSafety lost, it viewed this case as a call for future revisions and improvements.

Regulatory Gaps and Challenges

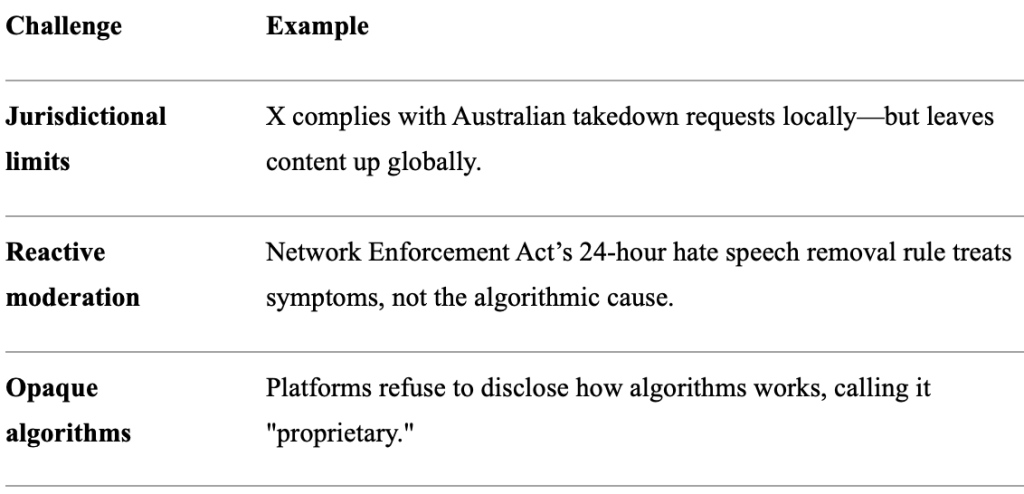

Like the tension between free speech and online harm, determining the appropriate level of digital governance remains a complex issue. Despite growing awareness of the risks posed by online hate speech, national governments and international organizations have largely failed to implement enforceable rules that hold platforms accountable. While some standards and limitations do exist, they rarely meet the scale or urgency of the problem. The challenges originate from jurisdictional limits, inadequacies in existing content moderation systems, and black-boxed algorithms. Together, these difficulties call for an overhaul of platform governance and accountability structures.

Table 1. Three Unresolved Challenges in Platform Governance.

Jurisdictional Issues and Global Accessibility

The internet has no borders.

The spread of harm has no borders.

Regulations do have borders.

Figure 4. Jurisdiction and Digital Policy Governance. (source)

Social media platforms such as Instagram, TikTok, and X operate internationally, however, governance efforts are restricted to jurisdiction boundaries. This creates a governance gap. Even if regulators issue orders, platforms can delay actions, partially comply, or only geo-blocking harmful content. Also, companies have the option to engage in forum shopping: locating their headquarters where more favorable laws apply. This points to the fact that digital laws vary significantly from country to country. What is protected in the United States, for example, might be illegal in Germany. Therefore, forum shopping grants companies the ability to do the bare minimum. In addition, speed is an integral part of online governance. While debates and court actions take months, algorithms transfer in milliseconds. Online harmful content would easily become out of control within current jurisdictional limits.

These jurisdictional limitations don’t just make enforcement difficult — they allow platforms to operate in a legal grey zone, where compliance is selective and accountability is optional.

To address these concerns, Woods (2021) proposes a statutory duty of care model that shifts responsibility toward platforms themselves. This model steers away from censoring individual content toward reducing foreseeable systematic risks. Inspired by workplace safety laws, this approach would require platforms to proactively assess and mitigate harms such as hate speech, disinformation, and algorithmic amplification. It introduces a legal obligation for platforms to produce risk assessments and demonstrate their safety processes, subject to oversight by independent regulators.

Reactive Moderation: An Afterthought

Reactive moderation refers to responding to harmful content after it has been posted, and often after it has spread widely, which is the dominant model for most social media platforms today. For example, Germany’s Network Enforcement Act mandates platforms to remove clearly illegal content within 24 hours and subtly illegal content within a week (Gesley, 2021). Another example is Meta, which heavily relies on user reports to flag inappropriate content and then decide whether to remove it or not (Zilber, 2025).

This practice misses the core problem: removing a video after it has 10 million views does not erase the impact it has on viewers and victims.

Figure 5. Post-Moderation. (source)

Moreover, it is also worth noting that reactive moderation can be selective and inconsistent. Roberts (2019) argues that content moderation is not a neutral or purely technical process, but one that fundamentally serves the economic and political interests of platforms. Factors such as a platform’s political alignment, economic interests, and regional regulatory pressure may all influence the speed or whether a piece of content is removed.

Due to differences in regulatory and political environments, Chinese social media platforms like Douyin and RedNote operate under a pre-publication moderation model. Content must pass a strict review process before it becomes publicly visible, which can take anywhere from a few minutes to several days. While this approach addresses issues associated with reactive moderation, it raises concerns about over-censorship and lack of transparency.

Opaque Algorithms: The Black Box

Most social media platforms use recommendation algorithms to determine what users see. These algorithms are proprietary and constantly evolving, making them a “black box” for regulators and users.

Figure 6. The Black Box. (source)

Major platforms often claim to disclose how their algorithms work, but these disclosures are often limited to broad overviews and guides. Critical details such as algorithmic weighting, underlying code, and training data remain secrets. This makes it difficult, if not impossible, for researchers or regulators to meaningfully audit or evaluate their systems. For example, Instagram states that its feed ranking is influenced by user activity, interaction history, and characteristics of both the post and its author. However, it does not point out how these factors are weighted or how they shape outcomes (Mosseri, 2021).

The Way Forward: Here is What Could Work

-Media Literacy.

Help the audience recognize manipulation tactics and emotional triggers.

– Support for cross-border regulatory cooperation.

Harm spreads globally, so enforcement and accountability should, too.

– Systemic accountability (statutory duty of care).

Platforms must be responsible for preventing foreseeable harm through design, not just content takedowns.

-Ethics: Balancing User Safety and Profit.

Platform decisions should prioritize user well-being, not just shareholder returns.

– Algorithmic transparency and access.

Disclosing how content is ranked allows independent experts to audit risks and propose meaningful recommendations.

-Stronger enforcement and penalties for non-compliance.

Regulatory frameworks should include real consequences when platforms fail to act, not just guidelines.

Figure 7. Internet and Structure. (source)

Fix the System, Not Just the Speech

In the name of free speech, platforms have too often deflected responsibility for the harms they help create. Online harm is not just about speech — it is about systems: jurisdictional limits, selective and reactive moderation, opaque algorithms, and the absence of enforceable governance that allows hatred and bias to thrive. Without structural accountability, these harms will continue.

Figure 8. Peace, Love, Unity, Respect. (source)

Rethinking digital governance means moving beyond content takedowns toward proactive, systemic reform. Reforms that hold platforms responsible not just for what they host, but for how they’re designed.

This was never a matter of speech versus silence.

It is, and always has been, structure versus chaos.

To build an online future filled with peace & love, we must stop asking who said it — and start asking why the system chose to amplify it.

References

Evans, J. and Butler, J. (2024). eSafety drops case against Elon Musk’s X over church stabbing videos. ABC News. [online] 5 Jun. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-06-05/esafety-elon-musk-x-church-stabbing-videos-court-case/103937152.

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms . Polity Press.

GCF Global. (2019). Digital Media Literacy: What is an Echo Chamber? [online] Available at: https://edu.gcfglobal.org/en/digital-media-literacy/what-is-an-echo-chamber/1/.

Gesley, J. (2021). Germany: Network Enforcement Act Amended to Better Fight Online Hate Speech. [online] Library of Congress. Available at: https://www.loc.gov/item/global-legal-monitor/2021-07-06/germany-network-enforcement-act-amended-to-better-fight-online-hate-speech/.

Gibbs, A. (2011). Affect Theory and Audience. The Handbook of Media Audiences, pp.251–266. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444340525.ch12.

Jensen, M. (2025). Hate speech on X surged for at least 8 months after Elon Musk takeover – new research. [online] The Conversation. Available at: https://theconversation.com/hate-speech-on-x-surged-for-at-least-8-months-after-elon-musk-takeover-new-research-249603.

Mosseri, A. (2021). Shedding more light on how instagram works. [online] Instagram. Available at: https://about.instagram.com/blog/announcements/shedding-more-light-on-how-instagram-works.

Roberts, S. T. (2019). Behind the Screen : Content Moderation in the Shadows of Social Media . Yale University Press,. https://doi.org/10.12987/9780300245318

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F. R., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021). Facebook: Regulating Hate Speech in the Asia Pacific. Department of Media and Communications, The University of Sydney. https://hdl.handle.net/2123/25116.3

Taylor, J., Rachwani, M. and Beazley, J. (2024). eSafety commissioner orders X and Meta to remove violent videos following Sydney church stabbing. The Guardian. [online] 16 Apr. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2024/apr/16/esafety-commissioner-orders-x-and-meta-to-remove-violent-videos-following-sydney-church-stabbing.

van de Kerkhof, J. (2025). Musk, Techbrocracy, and Free Speech. VerfBlog. [online] doi:https://doi.org/10.59704/0db298323048f15a.

Watson, K. and Mao, F. (2024). Sydney church stabbing: Religious community tensions run high. www.bbc.com. [online] 17 Apr. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-68832894.

Woods, L. (2021). Obliging Platforms to Accept a Duty of Care. In Martin Moore and Damian Tambini (Ed.), Regulating big tech: Policy responses to digital dominance (pp. 93–109).

Zilber, A. (2025). Meta apologizes after Instagram users are flooded with violent videos. [online] New York Post. Available at: https://nypost.com/2025/02/27/business/meta-apologizes-after-instagram-users-were-flooded-with-violent-videos/.

Be the first to comment