“I just want to play a game.”

This was the first time I saw the stranger who added my friend to the Honor of Kings international server send a cross-platform harassing and abusive message.

It all started in September 2024 when I accepted a friend application from a stranger on the Honour of King’s international server. After the stranger invited me to play a few games of double row, out of politeness, I accepted his cross-platform friend request, and he became my WeChat friend.

A week later, the strange man began to send suggestive messages. Immediately afterwards, he changed the name of the game to the sexually suggestive “My Brother 17.5 Cm”, and added my friend with another game account that was racist. I felt physically and psychologically disgusted, so I deleted and blocked 5 of his accounts on various platforms.

In October, when everything calmed down, I logged into the game to find that I had not only received multiple requests to add friends with racist IDs but also swam abuse in the gaming community. He even found another gaming account that I had only used once and claimed that “human flesh” had come to my name and address.

I blocked him, and changed the ID, avatar, gender, and region. I ran away. But the harassment caught up like a virus.

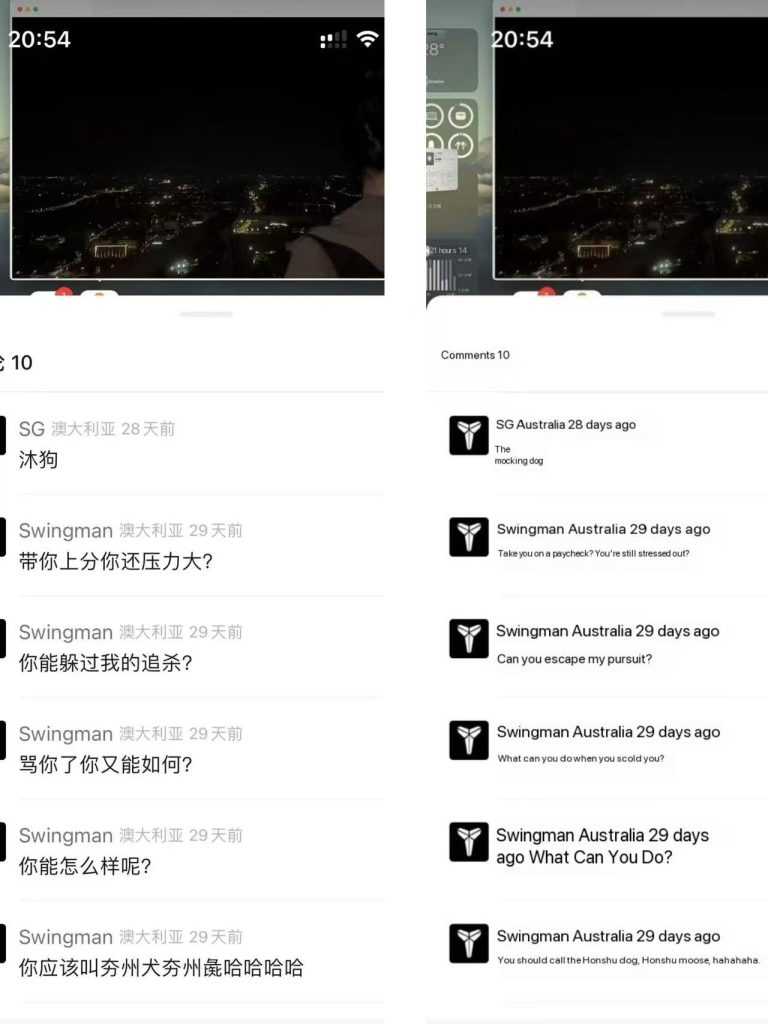

A screenshot of abusive remarks about the harasser

It’s not my own experience. From Twitter to WeChat, from meme pages to gaming platforms, social platforms are “acquiescing” to a new pattern of hate – one that doesn’t necessarily shout, but can do real harm.

In this blog, I will discuss how platformed racism and digital sexual harassment can be systematically permissively and even amplified through platform design, algorithmic mechanisms, and moderation choices.

What is Platformed Racism?

You may have heard someone say, “Social media doesn’t create hatred, it just reflects reality.” But that’s only half true. Social platforms are not only mirrors of reality, they are shaping reality.

Pierre Bourdieu first introduced the concept of cultural elements in his informal book Distinction (1979), referring to professional cultural agents such as journalists and arts producers who acted as go-betweens for high and popular culture.

Cultural intermediates should theoretically serve as a content filter, filter the appropriate content and present it to the user. Can it effectively filter out harmful hateful content? That is, speech that ‘expresses, encourages, stirs up, or incites hatred against a group of individuals distinguished by a particular feature or set of features such as race, ethnicity, gender, religion, nationality, and sexual orientation’ (Parekh, 2012, p.40).

The platform algorithms as cultural intermediates in social media not only do not play a role in the issue of racism, they not only reflect prejudice, but even intentionally or unintentionally spread, mutate, and even gain encouragement.

When the platform itself—through its rule design, recommendation mechanisms, and user interaction structure—is“helping” this hate speech spread, the problem is not just what the user says, but what the platform does.

This is the concept of “platformed racism” proposed by researcher Ariadna Matamoros-Fernández (2017): not only does users create hatred, but the platform itself “participates” in the generation and spread of hatred through design and mechanism. ). first, it evokes platforms as amplifiers and manufacturers of racist discovery and second, it describes the modes of platform government that reproduce (but that can also address) social inequality.

The platform’s recommendation algorithm and reporting mechanism is ineffective, the bias of review policies and the disregard of cultural background have all made places like Facebook, Twitter, and game social systems become hotbeds of hateful discourse.

Go back to my personal experience: the players who harass me used multiple game accounts, changed their IDs, changed their avatars, and made racist and sexually suggestive remarks – every time I block or avoid them, he always appears again.

A screenshot of nicknames for racial discrimination and sexual harassment

It’s not because I exposed something, but the platform structure allows it all. I can’t report effectively or confirm whether there is an administrator involved. The system does not have any real security network.

How should I escape Hate Speech and Online Abuse? Can I only “disappear” on the Internet forever and never use these platforms?

This is not just a problem of “some bad guy”, but a platform system acquiesces and even indirectly encourages such violent behaviours to occur.

Algorithms Don’t Hate People—But They Help People Who Do

As I mentioned earlier, the social platforms we use every day – Facebook, TikTok, Twitter, and even mobile games – are powered by a system called an algorithm. These aren’t neutral programs, and their goal is simple: to keep you on the platform longer, click more, and farm faster.

Everything seen in these platforms is not accidental: texts, pictures, music, videos – all of them are carefully selected to achieve a specific communication effect. And “hateful content” tends to do very well in terms of data.

In the case of Adam Goodes, the research found that a large number of memes and videos of racial attacks that maliciously mocked him spread rapidly through sharing, liking, and the platform’s referral system (Matamoros-Fernández, 2017, p 932).

Once these contents are interacted with by enough people, they will be judged by the system algorithm as “hot content”, thus entering the “green channel” of the recommendation logic. Networked hate is not a loud cry, but a creepy growth through sharing and interaction.

Back to my own experience: I had blocked five of the harasser’s accounts, but the other party found my other, even a barely used account. The harasser changed his social platform avatar to a photo of me and changed his nickname to an insulting nickname that included my real name, which contained slut-shaming and sexual harassment implications.

I didn’t send my real name, but after deleting and blocking him, I changed my nickname, avatar, gender, and even country and region, but he still did.

If he can track me down and tell me through a private message in the background of his WeChat video account, he knows my address area in Sydney, as well as my real name and photos I have previously posted on other platforms, which is called doxing (Flew, 2021, pp. 115).

It’s not that he is “smart” enough to hack into my information base through hacking techniques, but that the platform mechanism has silently betrayed me behind the scenes: it may be that functions such as friend recommendation system, IP recognition, and co-contact algorithm have become the “weapons” of the perpetrators.

I blocked and deleted the harasser, cleared social information on multiple platforms, and logged out of my account, but the harasser was unharmed.

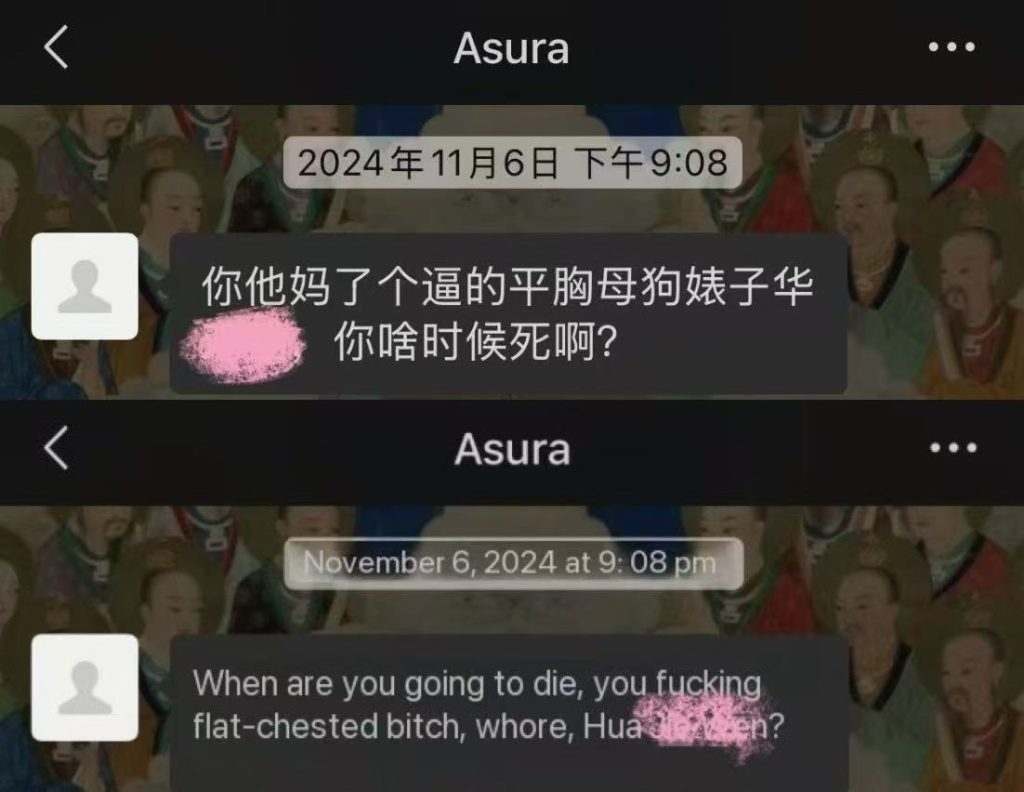

A screenshot of sexual harassment and intimidating remarks

I wanted to disappear, but the system pushed him back in front of me again and again.

Reporting Doesn’t Work the Way You Think It Does

When I was harassed at first, my first reaction was to report it – didn’t the platform keep saying “Please report if you have a problem”? I expect the platform to protect me, at least by banning the harasser’s account and preventing him from sending me curse harassment messages through all means. At the very least, let him change his insulting nickname and avatar – which violates my right to portrait and reputation.

But the reality is this:

Whether it is WeChat, Honor of Kings or Instagram, no option accurately corresponds to the “race + sexual harassment + cross-platform tracking” I encountered;

The reporting entrance of each platform is vague, most of them can only choose “spam content” or “inappropriate language”, and the reporting procedures are extremely cumbersome, the victim needs to provide pictures and text evidence, and the perpetrator only needs to insult him;

The feedback after submission was completely inconsistent with my expectations, and after other victims who had similar experiences to me also reported the harasser, we found that not only was the other person’s account not banned, but even the way the other party was abusive was even more unsightly;

The other party changed to a different account number to continue to harass, and because he used abusive words with “homophony”, the platform had no way to correctly assess the verbal harm when assessing it.

It’s not that “the system is buggy”, it’s that the system itself isn’t meant to protect me. And I’m not the only victim at all,

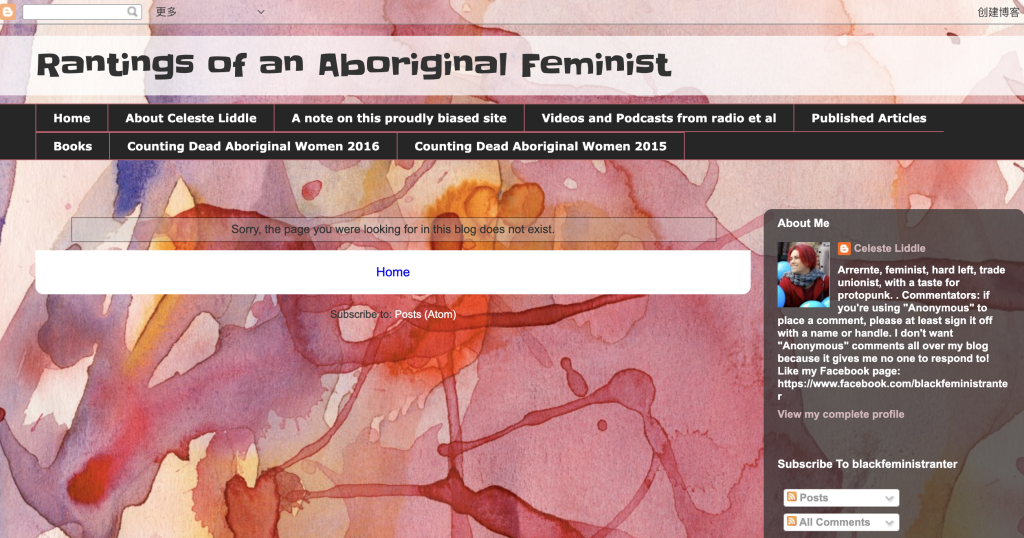

For example, in the case of Celeste Liddle, to counter some racist and sexually biased content in the trailer of an Australian comedy show, she posted photos of two indigenous women performing traditional rituals and some ironic words, but was banned by Facebook for “violating the nudity policy” for malicious reporting; A large number of pages with racist content have not been banned for years (Liddle, 2016, p931).

Liddle’s post has now been cleared due to reporting

Platforms choose who to deal with and who not to deal with based on cultural bias and business considerations. Far from being an “umbrella” for victims, the platform’s report button is on the contrary, it is a “PR show” for the platform most of the time. The platform shows the public that it will protect the rights and interests of users and the feelings of use, but it is almost useless.

Many netizens use social media to find that when they post hate speech, the statements of male accounts are less likely to be deleted by the platform, while the statements made by female accounts are easily banned, even if the language is not sharp. Content moderation is supposed to strive to create an inclusive, friendly void for all, but current practices embrace misogyny and apply it algorithmically (Marshall, 2021).

In the process of being racially attacked, sexually threatened, and cross-platform, I blocked, reported, changed my account, and deleted my friends…… Did almost everything I could counter up.

But the platform’s response has always been: silence.

Digital Violence Hurts—Even When It’s Invisible

Some people will also say, “Wouldn’t it be nice not to respond to him?” “Don’t take it too seriously, it’s just the Internet.”

But when a person comes to you across platforms, ridicules someone else’s ethnicity, sexually humiliates you, or even calls you to die – this is not an “online conflict”, but a psychological injury.

Hate speech fuels intimidation, discrimination, stigma and prejudice, and its victims find it difficult not only to participate in collective life, but also to lead autonomous and fulfilling lives. The target group is unable to relax and live without fear and harassment t’ (Parekh, 2012, pp. 43,45)

I can swap out everything – nicknames, avatars, genders, regions; I uninstalled the app to avoid logging in.

But the fear and shame never left.

Why am I the one to be ashamed of? And not that perpetrator?

In this case, the perpetrator and I did not have a deep emotional connection, and most of it was one-sided name-calling, after all, we were completely strangers who had spoken two words. Then does he hate me so much that he keeps chasing me?

I think the answer is no, and the perpetrator knowledge used me and the other victims as a punching bag, and when his life was not going well, he used abusive attacks to vent.

And the platform’s inaction fuels the flames of the perpetrators.

Platforms are not neutral. Behind every click, recommendation, and report is the choice of the platform designer. When the platform chooses neutrality between the abuser and the victim, its scales are already tilted in favor of the abuser.

I believe that platforms must:

Establish a “cross-platform harassment identification system” so that harassers cannot easily change their numbers;

Content moderation must be “transparent + culturally sensitive”, and bots can’t automatically delete it;

The reporting process should be “victim-centric”, providing feedback and support, rather than leaving behind a disclaimer;

Platforms must send a clear signal that “hate speech is not controversial speech, it is violence”.

At the same time, with the development of digital media, I believe that the government should intervene appropriately

It’s not a “troll” problem, it’s a digital culture that needs to be cured.

References

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating Platforms (pp. 115–118). Polity Press.

Liddle, C. (2016, March 14). Rantings of an Aboriginal feminist: Statement regarding the Facebook banning. Blackfeministranter.Retrieved from http://blackfeministranter.blogspot.com/2016/03/statement-regarding-facebook-banning.html

Marshall, B. (2021). Algorithmic misogynoir in content moderation practice | Heinrich Böll Stiftung | Washington, DC Office – USA, Canada, Global Dialogue. Heinrich Böll Stiftung | Washington, DC Office – USA, Canada, Global Dialogue. https://us.boell.org/en/2021/06/21/algorithmic-misogynoir-content-moderation-practice-1

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: the mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2017.1293130

Parekh, B. (2012). Is There a Case for Banning Hate Speech? The Content and Context of Hate Speech, 37–56. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139042871.006

Be the first to comment