Source: iFeng News.

A Death That Changed the Conversation

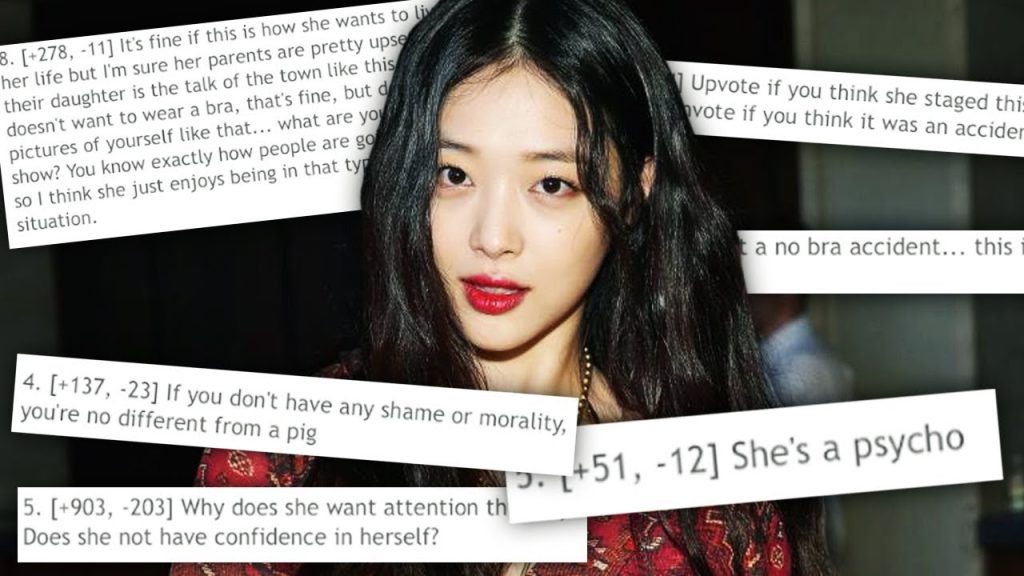

The news of South Korean singer and actress Choi Jin-ri, known by her stage name Sulli, is what shattered the hearts of Korean society and others on October 14, 2019. She had been 25 years old at the time of her death when the police later confirmed her death to be a suicide in her home. It was her life that had subjectively weathered years of online violence. Long before her death, Sulli(Choi Jin-ri)had faced ongoing cyberbullying that was vicious, dehumanizing, misogynistic, and wide-ranging across multiple social media platforms. Possibly Sulli’s story is most heartbreaking because she had begun to disclose the emotional and psychological impact of digital abuse before it finally became unbearable and took her life.

Sulli’s sad story compels us to deal with unpalatable questions related to our digital ecosystem. Is it possible that anonymous comments that take place on the internet could drive someone to take their life’s? The words do not physically hurt, but repeated, public, facilitated cyber harassment can be disastrous — largely even more so when compounded through algorithms and the limitations of weak moderation systems. It is not just an unfortunate event; it highlights core weaknesses in how we manage online spaces. A unique set of sanctioned circumstances, poor moderation systems, algorithms that incentivize trolling behavior, and more enable a total atmosphere of harassment. While all of these issues exist in South Korea’s exceptional digital culture — one that runs counter to the very restrictive social norms to which South Koreans adhere offline — these behaviors are endemic regardless of location. Sulli’s passing rightly reminds us that digital platforms can be real vehicles for harm, when poorly designed and managed.

Source: Pinterest. Creator unknown.

Unmasking Korea’s Digital Hostility

To fully understand why Sulli’s tragedy is not just an isolated case, it has to be analyzed in the context of Korea’s unique Internet culture. In South Korea, cyber violence has long been a common social phenomenon, and the worsening of the problem is closely related to the country’s unique Internet ecology. Since the abolition of the “real name law” in 2012, anonymous speech has become extremely common on Internet platforms. In popular Korean online communities such as Nate Pann and DC Inside, users can speak freely without being held accountable for their speech, completely concealing their identities. A 2020 report by the Korea Internet Service Agency (KISA, 2020) noted that while the anonymity mechanism protects privacy, it has also made malicious attacks significantly less costly, with a sharp increase in harassment against public figures in particular. Female entertainers have become one of the main targets of cyber violence. Statistics from Korea’s Ministry of Women’s Families show that more than 75 percent of female public figures have been subjected to cyberattacks because of their appearance, dress or gender perception. As an entertainer who openly supports feminism and challenges the traditional image of women, Sulli has naturally become the focus of malicious online comments. Sulli was constantly attacked with sexist and stigmatizing remarks for expressing feminist views and dressing freely.

The ultimate tragedy shows that the malicious speech indulged in by the culture of anonymity is not harmless, but rather a tool of violence that can be very harmful in real life.

Source: Freepik. Author unknown / Free for editorial use with attribution.

Algorithms: The Hidden Hand Behind Online Hate

These platforms are built on a complex array of content distribution algorithms that are designed to maximize user engagement. In The Atlas of AI, Kate Crawford (2021) explains that “these algorithms are often not constructed to promote the most rational engagement” and tend to favor content “that elicits emotional response.” In particular, anger and outrage tend to drive higher click-through and engagement rates than reasoned discourse. This is advantageous for the platform’s revenue, but it has the added benefit of distributing hatred and harassment. In Sulli’s situation, there are a number of Korean portals that did the same thing, including Naver’s hotlist, which always prominently featured bad news about Sulli, and in doing so, propagated toxic comments about her by encompassing that content into trending lists. Algorithms do more than simply provide increased eyes and/or views of harmful content; algorithms also legitimize that content by acknowledging its “hotness” and virtue and therefor mainstreaming it which encourages more unique users to engage and disseminate. Overall, algorithms serve as accelerants for instances of cyberviolence and transform an individual act into a digital siege.

In this way, platforms unintentionally perpetuate a harmful cycle. Initially created by a small number of users, the content swiftly spreads, reaching audiences that might not otherwise be involved and converting spectators into participants. Thus, algorithms are not neutral, but actually play a role in selective dissemination, spreading individual targeted attacks into collective cyberviolence.

Source: Marr, B. (2023, February 3). How to deal with cyberbullying at work [Article]. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/how-deal-cyberbullying-work-bernard-marr

Too Little, Too Late: Why Platforms Can’t Keep Up

Another key issue is that social media platforms mostly adopt “passive censorship”, i.e., they deal with content only after users have reported it. Analyzing Facebook’s hate speech management in the Asia-Pacific region, a team of researchers from the University of Sydney found that most social media platforms adopt a “passive review” model, which relies on user reports rather than active screening. Sulli’s case illustrates these issues vividly. Sulli and her company reported and complained about malicious comments on several occasions, but the platform only deleted individual content and took little or no action to ban the abusers. Domestic Korean platforms such as DC Inside and Nate Pann also generally rely on user reports and lack an algorithmic active identification system. This vetting lag creates a chronically unpurified online environment that continues to harm her mental health. The result was a persistently toxic environment where harmful speech remained largely unchecked.

In addition, passive vetting overly relies on keyword identification and is powerless against implicit harassment and psychological violence. Suzor (2019) refers to this phenomenon as the “digital space of anarchy”-platforms set their own rules but lack transparency and accountability. Users have no way of knowing how content is judged and processed. This invisibility reduces efficacy and trust by making it harder for users to understand how monitoring choices are made.

Source: Canberra Times.

Can We Fix the Internet? Here’s What Needs to Change

Addressing the problem of online violence cannot just be restorative reactive measures that mean waiting until the flame dies down. The platforms’ architecture needs to undergo systematic structural modification. Education in society, algorithmic openness, and legal legislation are examples of structural change.

The catastrophe regarding Sulli has caused South Korean society to fundamentally rethink the regulation of online violence. The National Assembly passed a landmark amendment to the Information and Communication Network Act in 2020 that came to be known as “Sulli’s Law.” This new law represents real progress, requiring large platforms to improve their user verification systems, as well as imposing legal sanction for malicious behavior online. The law faced backlash from privacy proponents who feared government overreach, however, the law has considerably reduced anonymous attacks by approximately 40% according to the Korea Communications Commission’s 2021 report. Once again, laws alone cannot address the myriad issues related to online violence. The law must also balance the individual privacy of users with their collective safety as a society, and will take time and continued work with legislators, digital rights organizations, and platform operators to develop sound content standards to ensure safety and good use, without preventing the use of platforms to express one’s views. Future iterations of the law should establish a more nuanced approach to the different ways online harm is experienced and escalated, because it is unlikely that a marketed one-size-fits-all approach will work for everything from celebrity harassing to daily forms of cyber bullying.

At the platform level, there is an urgent need to implement comprehensive transparency and user empowerment initiatives. In simple terms, platforms should be clear and plain about how their recommendation algorithms work and should allow users to meaningfully curating the content they see. As Suzor (2019) notes, to hold platforms accountable, they must be transparent about their internal content selection, sorting, and recommendation systems. Platforms also need to completely redesign their engagement systems – from incentivizing outrage and controversy to incentivizing meaningful positive engagement. Instagram’s addition of keywords that users can filter and option to hide comments indicates such interventions could work, as early reports indicate a 30% drop in reports of harassment after the implementation of these features. Such features could and should become the norm, as well as more advanced AI detection systems which could catch more subtle harassment that do not appear to be keywords. Importantly, though, platforms need to invest in human moderation teams with cultural competency to appropriately contextualize and assess reported content.

Though, the intention is the most effective option, our best long-lasting solution is to develop a more healthy digital culture through widespread education and cultural change. Digital citizenship courses should be added to school curricula, informing young users about their digital citizenship, including empathy, critical thinking, and responsible communication, in addition to the technical aspects of being a user. Activities in communities and communities can help augment this digital citizenship education for adult users, particularly adults who were not raised with social media. Research from Seoul National University indicates that schools educating students about online behavior had a 60% decrease in student participation in cyberbullying events. In addition to formal education programs, media literacy campaigns targeting all groups of users should also inform users of how to analyze (or critique) manipulative media and educate how crimes in the real world are consequential to internet behavior. Cultural institutions have a responsibility along with multiple forms of influencers to model how to behave online by calling out the culture of sanctioned digital cruelty and modeling how to develop positive online behavior. Altogether this process would create a cross-generational group of users educating one another to work towards an online culture that respects interpersonal and individual responsibility seamlessly incorporated into the normalized engagement vines of daily lives and societal acceptance of online violence. Helping to shortened conditional socialization of incremental increase and deterioration of online daily violence.

The death of Sulli serves as a reminder that online violence is absolutely not innocuous behavior in the digital sphere but rather a social issue that can be and is harmful. The only way that the Internet can become a true public space dedicated to safety is if platforms, legislators, and the general public take on the responsibility together. By elevating moderation, transparency around procedures and algorithms, and education, we can build more secure and safe online communities. If we are going to honor an individual like Sulli, we must contend with this structural issue in a serious and comprehensive way. Platforms alone are at fault and hold culpability, but legislators, educators, and everyone who uses the internet has some complicity. Only together, and only steadfastly, will we be able to build the safe, inclusive, and humane digital communities that we wish to cultivate.

Source: ComingSoon.net.

Moving Forward After Sulli

Sulli’s passing symbolizes not only a personal tragedy but also the systemic inadequacies of internet platforms in controlling behavior. Her killing is an example of online violence that happens when the design of the technology, the technology’s financial interests, and the social and cultural contexts in which the violence takes place coincide. While engagement-driven architecture frequently encourages negative content over civility and amplifies harmful content rather than controlling it, the anonymity offered by many platforms lowers the threshold around harassment by making offenders less accountable for their actions. At the same time, platforms’ reactive approach to content moderation—which is frequently hesitating and inconsistent—effectively allows abuse to persist until it causes more severe harm, which is frequently irreversible. These structural flaws foster an atmosphere that is favorable to harassment, which is typically experienced by minorities, women, and public personalities who challenge social norms, like Sulli.

Avoiding violence in the future will require a shift away from punishment-based remedial policies and towards movement-wide reform of platform infrastructure, norms of designing algorithms, and attitudes towards social media. Technologically, platforms need to transition from a passive moderation mode to a proactive set of safeguards, such as a real-time detection of toxic or violent behavior and de-amplification of abusive content, while also providing full transparency about those systems. Legally, platforms should be regulated in a manner that does not impede free expression but incentivizes them to create safer spaces. Culturally, we should address social dynamics that sanction cruelty online, especially the misogyny and schadenfreude that led to Sulli being harassed. Changes will only occur if all stakeholders (tech companies, regulators, users) understand that violence in cyberspace is violence. As we increasingly exist in online and offline space, “free speech” can no longer be an applicable excuse for violence and abuse. Our next step is to re-design our digital ecosystems to honour human dignity by design and create as many spaces for connection as possible where compassion is not sacrificed as collateral damage, instead of making that premise for violence. Sulli deserves and all internet-users deserve a better digital world. A digital world that does not allow violence against its most vulnerable for clicks and comments.

References

Crawford, K. (2021). The atlas of AI: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press.

Korea Internet & Security Agency. (2020). White paper on internet safety and cyberbullying. Retrieved from https://www.kisa.or.kr/eng/main.jsp

Ministry of Gender Equality and Family. (2020). Survey on digital gender-based violence. Retrieved from https://www.mogef.go.kr

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021). Facebook: Regulating hate speech in the Asia Pacific(Research Report No. 2021-01). Department of Media and Communications, University of Sydney.

Suzor, N. P. (2019). Lawless: The secret rules that govern our digital lives. Cambridge University Press.

Be the first to comment