Introduction

“I just made a few comments, but it’s none of my business.” This is probably what many netizens think when engaging in online controversies. In the virtual space, any comment seems to be costless and harmless.

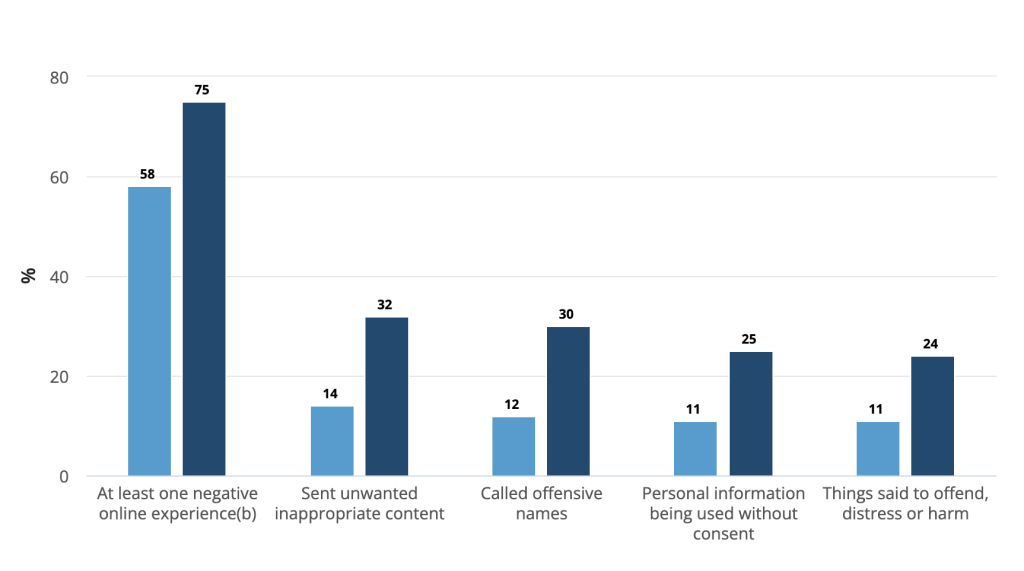

But instead, the data shows that the power of language is much deeper than we think. According to Figure 2 shows the Proportion of people aged 18-65 years who had a negative online experience(a) in the last 12 months. There are 75% of young people surveyed said they had encountered hate speech on the Internet, and more than half of them had developed negative feelings or even mental illness as a result. These figures show that hate speech is no longer just emotional expression but is evolving into a form of violence with real social harm (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2023). As media scientist Flew (2021) points out, digital platforms are not just neutral technology tools; they are actually, hence, in control of the public sphere and civic discourse, deciding what will be seen and what will be silenced. This blog post will analyze a specific case: Why does hate speech always top the trending searches? How do the platform algorithms and governance mechanisms allow it to be amplified step by step? Behind all this, is the platform really just “unintentional”?

Hate Speech as Structural Harm: Not Just Free Expression

Figure 3. Representation of algorithmic monetization. Image retrieved from Google Images.

In the online world, we often think of hate speech as “emotional venting” or “language conflict,” but this is, in fact, a misperception that underestimates its harmful effects and obscures the structural oppression it poses to certain groups. As Sinpeng et al. (2021) define, hate speech is not just offensive language, but an act that reproduces structural inequality, ranks targets as inferior, and restricts their capacity to speak back. It legitimate discriminatory behaviour and marginalization by embedding existing social hierarchies into online discourse.

At the same time, and to complicate matters further, hate speech is often difficult to define, and it is sometimes hard to tell whether it is genuinely malicious or not. It may be packaged as “teasing,” “joking,” or “free expression,” which sounds less severe but, in essence, still humiliates, demeans, and intimidates a particular group of people. The lethality of such language will not only hit the emotional and mental health of individuals, but also be rapidly amplified under the recommendation mechanism of social platforms, and unwittingly become a “digital weapon” – not only causing verbal harm, but also promoting the spread of structural inequality.

From Pink Hair to Tragedy: How Platform Algorithms Amplified Online Hate

What may seem like mere “teasing” can become digital violence once amplified by platform algorithms. In 2023, such damage fell precisely on the Chinese girl Linghua Zheng. She is not a public figure, but in the vast whirlpool of public opinion, she became a victim of hate speech.

According to Figure 3, In 2023, Zheng shared a photo on the social media platform showing her master’s acceptance letter to her grandfather in his hospital bed. In the picture, she is shown with dyed pink hair and a smile, documenting a heartwarming family moment. However, this originally happy photo was maliciously misinterpreted and wildly reproduced in a short period, quickly evolving into cyber violence.

Some netizens rumoured that she was a “chaperone” and that she was “putting on a show through her grandfather.” The content spread in the comments section and boarded the platform’s hot search list, triggering many onlookers and retweets. Her personal information was exposed, and social media platforms were filled with humiliating, mocking, and even cursing language. Although Linghua Zheng posted several clarifications afterward and even had her alumni publicly speak out on her behalf, online public opinion still did not stop the rhythm of attacks. In the face of constant online violence and malicious speculation, Linghua Zheng eventually found it difficult to self-regulate. Shortly after being diagnosed with moderate depression, she chose to end her life.

In addition to those netizens who think they are “presiding over justice,” the platform’s role as a “booster” in the entire incident is also worthy of vigilance. As soon as Linghua Zheng’s case became a hot topic on Weibo, the heat of related topics quickly increased, triggering many discussions. The Weibo recommendation mechanism quickly pushed relevant content, triggering large-scale discussions. When you open the Weibo homepage, users will see pictures of pertinent topics directly in the recommendation column “Guess you want to see.” Even after Linghua Zheng’s death, the relevant content has not been removed. The relevant entries remain on the hot search list.

In the current public opinion environment, women’s topics often carry their heat and antagonism, while physical appearance, speaking style, and even posting gestures can all become reasons for labelling attacks. Linghua Zheng was quickly labelled on social media platforms for her pink hair, female identity, and expression of “showing filial piety” and became embroiled in a highly gendered controversy. When the platform algorithm pushes these contents, it ignores the real situation of the individual and pays more attention to the emotional tension and topic heat, so the individual is moved to the centre of the storm and suffers huge cyber violence. This incident is not a simple “netizens out of control,” which fully demonstrates how hate speech spreads rapidly and causes real harm under the combined action of platform algorithm, social prejudice, and labelling mechanism.

The harms of such platform mechanisms are not limited to any single country. In June 2024, Amnesty International criticized social platforms, including TikTok and Instagram, for the mass removal of health information related to abortion care, including guidance content and contact information for non-profit organizations, following the overturn of Roe v. Wade in the United States. This behaviour shows that platforms can control what happens and how something spreads. When a rational expression is suppressed, and content containing hate speech is continuously exposed, we can foresee how many more tragedies will be repeated in the future. But is it just that algorithms “inadvertently” amplify hate? Why do platforms always push these comments, always slow to address them, and why do they never really stop the spread of hate?

Emotion Over Information: The Business Logic of Hate Speech

To understand why hate speech always appears on the home page or at the top of the trending lists, one needs to look at the underlying logic of the platform’s algorithm: it is not “content-first,” but “emotion-first,” not “information-value-oriented,” but “engagement-oriented.” When platforms treat controversial language as a trigger for user activity, hate speech quietly gains a visibility advantage. An elementary logic is that angry comments, inflammatory statements, and opposing opinions lead not only to catharsis but also to “likes,” “retweets,” “comments,” and extended stays of users. These are the most “valuable” data assets in the eyes of the platform.

In 2024, University College London experimented. This research signed up for several new TikTok accounts to simulate the browsing behaviour of average teenage users. while after five days researchers said the TikTok algorithm was presenting four times as many videos in derogatory and offensive content posted, which increased from 13% of recommended videos to 56%. Meanwhile, some videos that suggest constructive discussions or clarify gender misconceptions have received little attention (The Guardian, 2024). This is not an accident but a direct result of algorithmic bias.

This “interactive first” algorithm is not only the technical design of the platform but is deeply bound to the business structure behind the platform. The platform’s primary source of revenue is advertising, and the placement of advertising depends on the number of clicks, time spent, and activity of users. In other words, the core logic of the platform to make money is: the longer you stay, the more intense the debate, the more data, the more cash.” Some researchers have observed that “many platforms take advantage of platform policies that often value aggregating large audiences while offering little protection from potential harassment victims” (Massanari, 2015). Hate speech can precisely provide such high-stickiness emotional stimulation, so it has changed from “risk” to “asset” in the technical system of the platform.

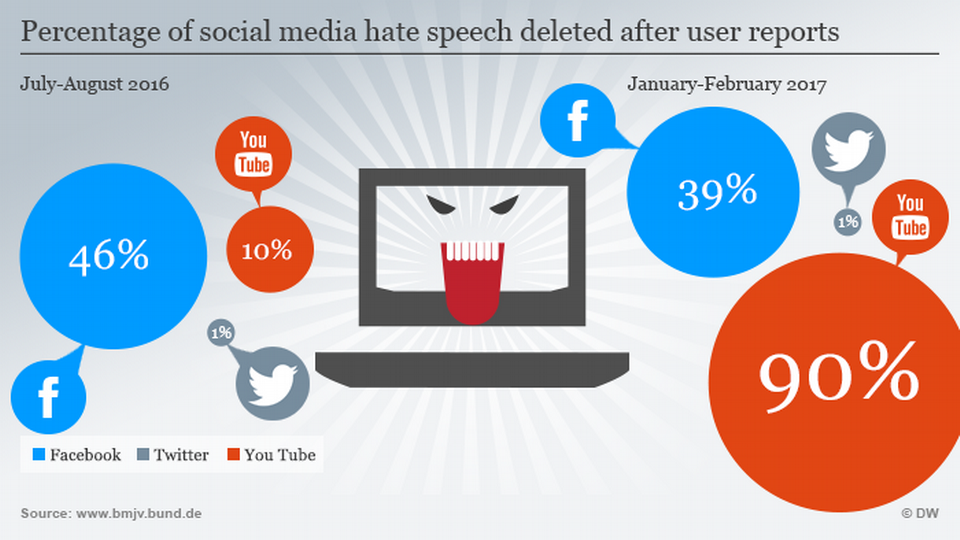

Media scholar Terry Flew has pointed out that platforms are not neutral information intermediaries but play the dual roles of “opinion builders” and “profit carriers” simultaneously. He criticized many platforms for adopting “symbolic governance” – setting up platform community norms and claiming to combat hate speech on the surface while ignoring high-interaction hate content at the institutional level because it generates real data and advertising revenue (2021). In other words, it is not that the platform cannot clean up hatred, but that it has never sincerely wanted to “lose the way to make money in exchange for fairness.”

This logic is particularly evident in Facebook’s platform practice. While Facebook ostensibly cracks down on hate speech, its enforcement in the Asia-Pacific region has long been plagued by double standards and sluggish governance. A large amount of hate speech content reported by users is retained because it did not breach ‘internal thresholds’ of the platform.” Even when violations are identified, the platform is still dealt with slowly. One of the key reasons is that this kind of content tends to generate a lot of “likes,” “comments,” and “retweets,” the interactive data that is the basis of the platform’s business model to make money (Sinpeng et al., 2021). In other words, in the eyes of algorithms, they are “high-value content” that platforms are reluctant to remove easily.

Meanwhile, Facebook has demonstrated another form of “laissez-faire” in India. In the face of inflammatory hate speech, the platform has chosen not to act, not because the content itself is popular, but because it fears angering the ruling party and affecting its policy interests in the local market, damage the company’s business prospects in the country (Sinpeng et al., 2021). This shows that whether encouraging “high interaction” or avoiding “political conflict,” the content governance behaviour of the platform points to the same core – maximizing commercial interests. As Flew (2021) criticized, this “symbolic governance” is not a lack of platform capacity but a choice of heat and resources, allowing hatred to continue to spread.

The responsibility of individuals and platforms, and why the platform faces the reality

If the platform mechanism is the driving force behind the spread of hate, returning to the root of the problem, we must also ask: What responsibility should platforms and individuals bear in the face of hate speech? First, as the starting point of information flow, the user must take responsibility for their expressions. No longer use “I just made a comment” and “it has nothing to do with me” as the reason to push away the harm caused by language violence. Nowadays, when the platform mechanism constantly amplifies individual voices, freedom of expression should not be abused. However, it must be accompanied by awareness of and responsibility for the consequences of expression.

At the same time, as the builder of public opinion discourse, the platform’s governance can no longer be limited to passive means such as “deleting posts and blocking accounts.” However, it should shift to more forward-looking design governance. The platform has the obligation to take user safety into account at the early stage of system design rather than waiting until public opinion is out of control and harm occurs. This means that the responsibility of platform governance is not just to “respond to user reports” but to proactively build a more psychologically safe communication environment.

Of course, reforming platform governance is not easy. On the one hand, the boundary of hate speech is blurred, and society still disputes the boundary between “freedom of speech” and “content harm.” On the other hand, in a business structure that relies heavily on advertising, few platforms are willing to sacrifice traffic to limit highly interactive content. For capital-driven platforms, clamping down on hate speech can mean lower earnings, lost investment, or even a loss of competitive advantage.

Conclusion

Reviewing the whole blog, we can find that hate speech is not a simple problem of users’ speech intolerance, but a kind of structural violence that is constantly amplified under the joint action of platform logic, commercial profit and social prejudice. Linghua Zheng’s tragedy is not an isolated example, but it reveals a deeper reality: in traffic-oriented systems, platforms are often more inclined to make hate “visible” and increase the heat.

It is not easy to change all this. We cannot end hate speech with a single deletion or a single report. it is a structural and long-term battle for both platforms and individuals, and therefore all the more reason to keep reflecting, resisting, and speaking out. The platform can create hate or amplify goodwill, it depends on who we choose to give our attention to and whose voices we choose to lift.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2023). Online safety. Australian Government. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/measuring-what-matters/measuring-what-matters-themes-and-indicators/secure/online-safety

Massanari, A. (2017). #Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures. New Media & Society, 19(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815608807

Flew, T. (2021). Hate speech and online abuse. In Regulating platforms (pp. 91–96 [115–118 in digital ed.]). Polity Press.

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021, July 5). Facebook: Regulating hate speech in the Asia Pacific. Final report to Facebook under the Content Policy Research on Social Media Platforms Award. University of Sydney & University of Queensland. https://r2pasiapacific.org/files/7099/2021_Facebook_hate_speech_Asia_report.pdfLinks to an external site.

Weale, S. (2024, February 6). Social media algorithms ‘amplifying misogynistic content’. The Guardian.

Be the first to comment