The phrase “Privacy is a human right” appears mostly through statements made by technological companies who present themselves as advocates of user rights. But what does it mean when privacy becomes part of the products tech companies sell? Online privacy continues transitioning from its inherent human right status to become an item for sale by companies that control and market our private digital information.

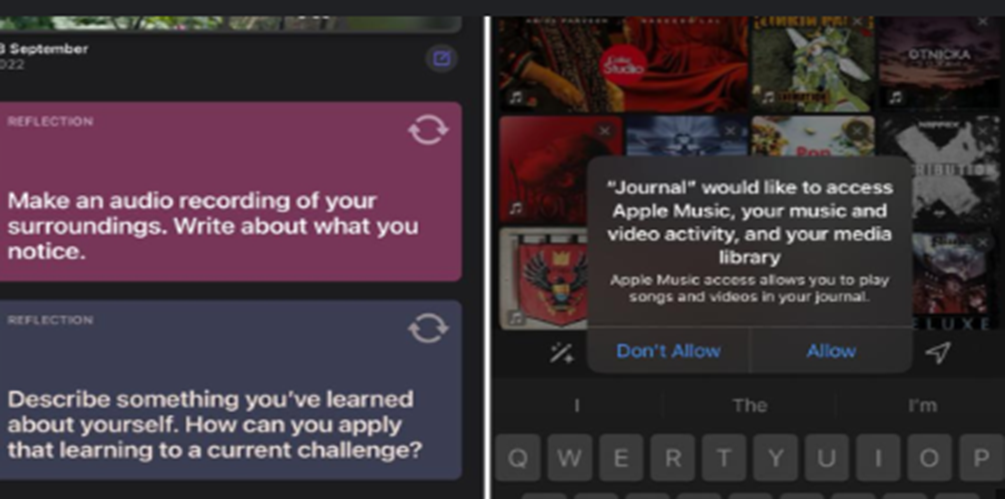

Apple’s Journal application released with its iOS 17.2 does raise significant questions over users’ digital rights especially how the rights are defined, commodified and governed within the current platform economy. The Journal app promotes itself as a privacy respecting mental wellness solution which uses on-device learning algorithms to analyze user moods through behavioral signals such as position tags, general activities and writing patterns to create online diary entries (Rene, 2024) . Apple advertises the Journal app as groundbreaking private AI technology yet the app itself represents a deeper contradiction since privacy now operates as both an area of surveillance protection alongside being a method of corporate governance control.

The blog post presents the argument that Apple Journal Application is an example of privacy platformisation in which user digital rights are being redefined as a product and that corporate governance is shaping digital autonomy.

Apple’s Privacy Paradox: Selling Privacy by Tracking Emotion?

The Journal application from Apple presents an initial appearance a win for users that are concerned about privacy. The entire operation takes place on the device while keeping information away from cloud storage and activating device-based machine learning to provide personalized journal content from user-provided data such as location information, images, calendar bookings and system interactions (Apple, 2024). The company insists that process operations on the Apple devices remain private since the platform prevents data transfer outside your phone without explicit user permission (Apple, 2024). The design is connected to Apples privacy marketing message that user privacy is an inbuilt and not bolted on feature on its application.

However there is a challenge: The main issue is that your emotional state is determined by the app using inferred data through behavioral signals such as writing style and movement patterns. The ambiguous aspects start to appear at this point. How does your phone guess your emotions for the purposes of journal guidance while working with assumptions about your personal information? Which assumptions does the program base its operations on? What data and models support those assumptions? And what is going to happen when the boundary between individual well-being and commercial product design creation starts to distort?

It is critical to note that the Apple application does not involve direct data theft or surveillance practices. The transformation of privacy is subtle and its redefinition is minimal which Nissenbaum (2018) calls “contextual integrity.” Nissenbaum outlines privacy protection as the practice of letting information move through social domains which match social requirements based on environmental settings context. At the same time privacy is not only about secrecy and anonymity. Therefore even when Apple is not exporting my data in the application the use of my data to shape my emotional engagement even internally forces an essential examination of digital environment consent as well as control and contextual boundaries.

Hence privacy has become less about data collection ad more about governing how the platforms are designing user experiences that are based on data driven assumptions. Please note that the Journal app does not operate against your privacy terms but redefines them by using emotional expressions as foundation for platform interactions.

Platform Power and Invisible Governance

Who is determining online privacy norms?

Suzor (2019) explains platforms such as Apple function as private regulatory bodies because they establish all fundamental rules and digital boundaries which govern online behavior. Each platform independently authorizes their Terms of Service while using individual data for interpretation purposes without including user input in their enforcement decisions. The user privacy terms are complicated and complex using legal terminology that most users find practically unreadable since they face a simple choice of acceptance or exclusion from using the application.

Suzor describes this practice as “lawless governance” because corporations control digital rights on their platforms with no obligation to users (2019). Individuals using Apple’s Journal app experience particular challenges due to its governing terms. The app initiates users to share personal emotional data yet provides zero clarity about how their information gets processed and managed. The public lacks any insight into emotional inference algorithms Apple uses in addition to lacking access to independent audits attesting to their accuracy and fairness.

The power dynamic is not equal as it is Apple that defines what “privacy” means within the application systems; and users have to trust the Apples definition of “privacy” without question. According to Suzor this type of invisible governance system creates norms which represent potential risks (2019). A wellness technology device may develop into behavior control, monitoring and surveillance tool under different circumstances or changes in corporate strategies.

The fundamental problem with governance relates to privacy because it extends beyond personal choice to include who holds the power to not only defines privacy but also to implement rules and enforce the rules of the individual choice. The Apple journal application is dominated by the company and its users are using the app which is governed by not only invisible but also rule-makers who are unaccountable to no one.

Rights as Features: The Platformisation of Privacy.

Why do we use the digital tools even though we express our skepticism about the data practices?

According to Flew (2021) we observe platformisation of regulation through which private technology corporations both facilitate services and determine the fundamental rules governing user rights. In this context, platforms like Apple recast fundamental digital rights as product features. Today privacy exists as a marketing tool which Apple integrates within Journal to help users feel comfortable while presenting itself as user-friendly before consumers.

Flew emphasizes that the approach reinforces and adds to the economic and political power of platform corporate objectives (2021). The privacy-centric branding of Apple separates this tech giant from Meta and Google which promotes the company to gain moral authority during digital ethics discussions. Apple maintains operations that processes and infers personal information though it uses terms that seem acceptable to users. The Journal app does not transfer data to external entities but it continuously analyzes user information that users can’t observe.

The process generates an incorrect belief in personal privacy data and safety empowerment according to Goggin et al. (2017). Users have a mistaken belief that they retain control of their data while they engage with pre-built systems that Apple developed without user participation. The platform operates as both safeguard and access control entity which determines how digital rights achieve visibility and protection status.

The situation extends beyond technical boundaries because it exists predominantly as a matter of political control. When the design becomes the way for a platform to define rights over law then the platform is bale to shift power into their hands. The Journal application demonstrates how a seemingly empowering tool exists inside standardized controls under corporate management.

Emotional Surveillance and the Ethics of Inference

Apple Journal stands out as controversial because it operates through inferred data which detects information about your emotional state by analyzing system predictions of your internal feelings rather than direct user actions. User mood surveillance depends on detecting typing speed and application usage along with voice analysis and behavioral indicators. Applications which collect inferred data have led to widespread ethical debate because Apple promotes such features for improving journaling and mental health despite their questionable nature.

The system uses emotional surveillance tactics which prove more risky than traditional monitoring methods because these techniques function beneath conscious awareness. Users often lack awareness about tracking of their feelings or the processing of such data. According to Karppinen (2017), modern digital rights require addressing the manner in which technology redesigns human subjects, their self-perception and autonomous abilities together with emotional experiences. A platform can implement emotional inferences to initiate behavior modification or product recommendations and detect irregular actions or manipulate content through mood-based decisions. Users remain unaware about how their classifications happen because the underlying processes operate through proprietary methods.

The lack of clear accountability allows emotional AI systems to transform users from participants to subjects who become measurable through predictive emotional assessment.

Privacy Isn’t Dead— It Is Being Repackaged

The attitude toward this situation tends toward skepticism because privacy acts as a commodity that is being marketed while ethical boundaries get gradually eroded. Digital rights need a transformation according to Suzor (2019) to reimagine digital rights is to ensure that user agency, accountability, transparency and collective governance is implemented. The Apple journal has have become essential aspects of digital-everyday living life so we should work toward changing their methods of privacy and data control as complete elimination is not a viable option.

The redefinition of privacy requires both better rules for regulating emotional data along with explicit requirements for obtaining informed consent. Nissenbaum (2018) explains that privacy protects appropriate social information flow which must include proper interpretation and usage of emotional and mental state data. The emotional tracking features of the Journal app demand society to redefine digital privacy boundaries in modern times. People should have transparent access to data handling practices since their mental health information represents protected personal status.

Demands for strong legal protection mechanisms are vital for digital identity protection since they prevent users from hidden opaque governance activities of platform systems (Goggin et al., 2017). Such protective measures extend beyond personal data security by maintaining digital rights of individuals who provide sensitive information to Apple’s Journal app. The psychological advantages of the app generate substantial privacy and autonomy concerns. Therefore protection of fundamental rights extends past data protection to include the right to determine personal information and maintain ownership of digital identity. Distinguishing ownership between these rights remains the main obstacle while determining their governing authority. People need to decide the fundamentals about digital self-governance since the current challenge extends beyond data ownership to rule-making authority over digital identities. A review of present legal structures becomes essential because corporate interests must not infringe upon individual rights.

Final Thoughts

The Journal app from Apple presents privacy as a feature component that redefines online privacy standards. As a mental wellness solution marketed under privacy protection guarantees the application creates doubts about data ownership as well as digital privacy definitions. Through emotional data analysis Apple creates new approaches which redefine privacy standards by making privacy requirements subject to corporate moderation. At the same time the inferred emotional analysis of the app, users remains unaware about how their emotional information gets interpreted and utilized by platform management systems. Digital platforms have evolved a new method to define privacy by designing systems that exercise control over their users’ online experiences. The true problem goes beyond data collection because it affects our understanding of digital rights and autonomy within corporate control in the current digital landscape. The redefining of user data digital rights holds deep importance to all of us. Each person should reconsider their relationship with tech companies because those companies control our platforms and construct the terms of privacy along with the boundaries of autonomy. The modern concept of privacy conflicts with established definitions of rights along with consent because it forces us to rethink digital life administration. We need to urgently address this complex situation through stronger accountability measures and better transparency alongside improved regulations which allow users to maintain control of their data.

References

- Ahmed, N. (2024, January 5). Apple Journal app review: Makes clever use of on-device data to generate prompts. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/technology/internet/apple-journal-app-review-a-close-look-at-apple-journals-data-driven-prompts/article67708911.ece

- Apple. (2024, September 20). Journaling suggestions & privacy. Apple. https://www.apple.com/legal/privacy/data/en/journaling-suggestions

- Flew, Terry (2021) Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity, pp. 72-79.

- Goggin, G., Vromen, A., Weatherall, K., Martin, F., Webb, A., Sunman, L., Bailo, F. (2017) Executive Summary and Digital Rights: What are they and why do they matter now? In Digital Rights in Australia. Sydney: University of Sydney. https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/17587.

- Karppinen, K. (2017) Human rights and the digital. In Routledge Companion to Media and Human Rights. In H. Tumber & S. Waisbord (eds) Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge pp 95-103.

- Nissenbaum, H. (2018). Respecting context to protect privacy: Why meaning matters. Science and Engineering Ethics, 24(3), 831-852.

- Rene, H. (2024, November 26).I am still trying to love Apple’s Journal app, but it is complicated. Medium. https://medium.com/macoclock/i-am-still-trying-to-love-apples-journal-app-8363f59743bd

- Suzor, Nicolas P. 2019. ‘Who Makes the Rules?’. In Lawless: the secret rules that govern our lives. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 10-24.

Be the first to comment