Tragedy turns China pink: The cost of online hate speech

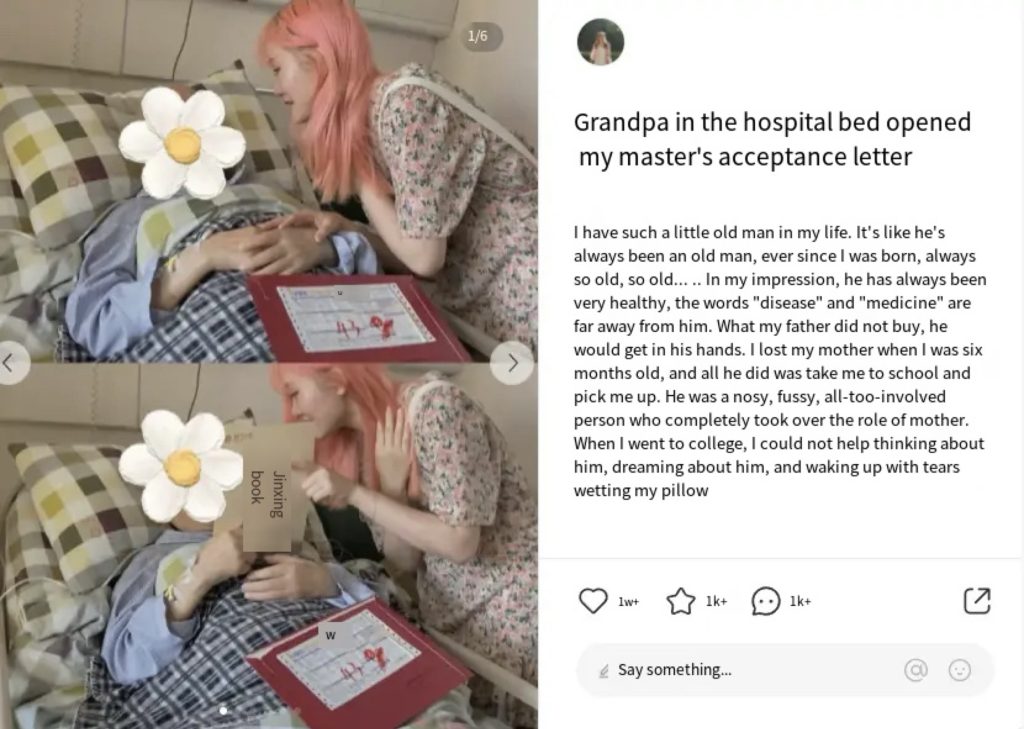

On July 13, 2022, Zheng Linghua, a 23-year-old girl from Hangzhou, Zhejiang, went to visit her bedridden grandfather with her master’s admission letter. To share her joy, she posted a photo with her grandfather on social media. In the photo, she has beautiful pink hair. However, instead of being congratulated, Zheng Linghua’s joy attracted fierce attacks on the Internet. Strangers on Chinese social media mocked and humiliated her appearance, accusing her of being unsuitable for teaching with her bright hair. Some netizens even spread malicious rumors, claiming that the bedridden old man in the photo was her “godfather” rather than her grandfather. Bhikhu Parekh (2012) said that hate speech often “stigmatizes the target group by explicitly or implicitly attributing characteristics that are generally considered extremely unpopular to it… [thereby] treating the target group as an unwelcome existence and a reasonable object of hostility”. Zheng Linghua’s pink hair, an innocuous feature, became a flashpoint for online moral outrage, turning into a flashpoint for misogyny and public shaming.

Figure 1: Zheng Linghua took a photo with her bedridden grandfather holding her admission letterOne particularly vicious comment, saying that a graduate student with pink hair looked like a prostitute, received more than 2,000 likes overnight (Tone, 2023). The message was clear: How dare a young woman celebrate her success against a backdrop of pink hair? The harassment never stopped. Zheng Linghua tried everything—she even cut her hair short and dyed it black in the hope of quelling the farce. She sought legal aid to try to stop the defamation. But months of constant online violence plunged her into severe depression (Tone, 2023). In January 2023, Zheng Linghua committed suicide, leaving behind a note blaming “countless anonymous cyber attackers” for driving her into despair.

“Today it’s a hair color issue, will it be a skirt issue tomorrow? … Do Chinese women have to wrap themselves in black cloth too?” one Weibo user wrote angrily, criticizing cyberbullies for controlling women’s personal rights (Tone, 2023). Zheng Linghua’s death shocked netizens. People began to mourn the girl and express anger at the injustice. Why does hair cause such serious online violence? Some people dyed their hair pink to show their support, chanting “Pink is not a sin, violence is a sin”

“Pink is not a sin, violence is a sin”

Zheng’s case highlights how traditional gender norms and moral judgments are reflected online. In China, some people believe that a female teacher should not have bright hair, but is professionalism tied to appearance? The insults directed at her were clearly gendered hate speech, an attempt to shame her for not meeting norms. It was a twisted form of social media lynching, with trolls acting like moral police. And the online environment—which is largely anonymous—has been shown to reduce users’ moral sensitivity through the perceived moral intensity of hostile comments, leading to online shaming (Ge, 2020). When cyberbullies don’t face immediate consequences (after all, it’s just a comment on an app like Xiaohongshu or Weibo), the momentum of the mob attack grows stronger. By the time a real authority figure or platform administrator intervenes, Zheng’s mental health has already been damaged.

From student to celebrity: the global nature of cyberbullying

Zheng’s story is heartbreaking, and not an isolated one. All over the world, women are attacked online for simply being themselves, and the consequences can be tragic. In South Korea, K-pop star Sulli (real name Choi Jin-ri) was subjected to years of vicious comments—brutal insults about everything from her private life to her views on women’s rights. In that year, there wasn’t much attention paid to women’s rights. Sulli was outspoken and free-spirited, but every time she pushed boundaries, the internet’s response was brutal. In 2019, at the age of 25, Sulli was found dead by suicide; multiple media outlets linked her death to depression exacerbated by cyberbullying. These tragedies highlight a common situation around the world: online hate and harassment can destroy lives. As Lee Dong-gyu, a psychology professor at Yonsei University in Seoul, pointed out after Sulli’s death: Free speech is important, but “insulting and undermining the dignity of others goes beyond the boundaries of free speech” (Shin et al., 2019).

Figure 2: Photo taken on October 16, 2019. Sulli has been described by her fans as someone who spoke out for women’s rights Source: Reuters

In the United States, Nina Westbrook – who herself is not even a celebrity, but the wife of NBA player Russell Westbrook – has received a large number of harassment and death threats from angry sports fans. In 2022, she publicly stated that she was “harassed every day because of basketball games” and received “abuse and death threats” against her and her children. Just because her husband had a bad season, strangers felt entitled to tell Nina that her family should die. As she said in her moving words: “This is not a game… This is my life, my children’s life… Shaming anyone for any reason is not the answer.”

Russell Westbrook also expressed the same protest in a press conference, which sparked a public discussion about sports culture and online bullying. Even NBA legends like “Magic” Johnson have spoken out, calling the threats against Westbrook’s family “completely unacceptable” and urging fans to remember that athletes and their loved ones are people first – no matter how they perform on the court, they should be respected.

The global prevalence of online violence

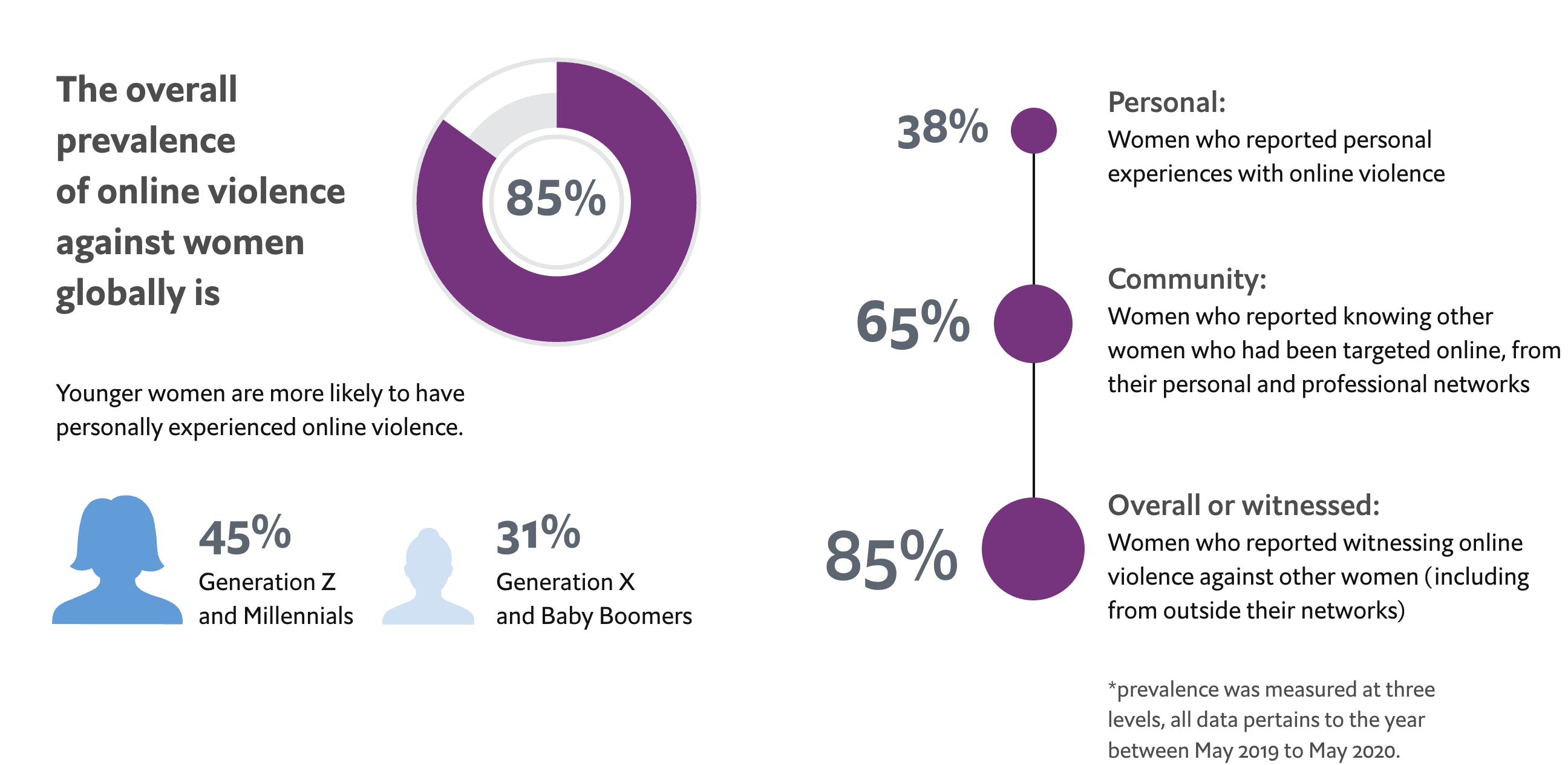

It’s easy to think that these cases are just rare, extreme cases. Sadly, they’re just the tip of the iceberg. Online hate against women is a global problem — across countries and cultures, digital platforms are rife with harassment, particularly against women and girls. Let’s look at some statistics: a recent international study by the Economist Intelligence Unit (covering women in 51 countries) found that 38% of women have experienced online violence, and a shocking 85% have witnessed violence against other women (The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2021). Think about it: if you’re a woman, there’s a good chance you’ve been attacked, or at least witnessed another woman being attacked. Those odds are pretty scary.

According to Gelber, the “systemic discrimination approach” definition of hate speech explicitly states that a person’s speech is oppressive when it is discriminatory against a marginalized group. In summary, this means that hate speech is discriminatory speech that targets a target audience, denies them equal opportunities, and violates their rights (Gelber, 2019). This makes gendered hate speech more than just offensive—it becomes a mechanism of oppression that denies women equal participation and violates their rights in much the same way as institutional discrimination.

This view is echoed in the report Facebook: Regulating Hate Speech in Asia Pacific, which found that gender-based hate speech is often ignored or under-regulated on social media platforms compared to racial or religious hate speech. Platforms and users often fail to appreciate how misogynistic content creates inequality, especially when combined with other forms of marginalization such as sexuality or race (Sinpeng et al., 2021). As a result, gender-based online violence not only harms individual women, but also involves wider discrimination.

Hate speech initially triggers “psychological symptoms and emotional distress” but may also change victims’ behavior to avoid being attacked again, limiting their ability to participate in society (Matsuda, 1993). Hate speech is therefore more than just an emotional offense; it is a structural harm that threatens personal dignity and the ability to fully participate in public life. Many women respond to online violence by hiding. According to research by the Economist Intelligence Unit, after being harassed, a third of women said they would reconsider expressing their opinions online, and 7% of women surveyed lost their jobs due to online violence. 35% of women have experienced mental health problems, and one in ten have suffered physical harm as a result of online threats (The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2021). In other words, women are being silenced. They self-censor or log out of their accounts to avoid being victimized again. This is depriving women of their voices, perspectives, and contributions in the digital public sphere. When we lose women’s voices, we all lose—our online spaces become less representative, less diverse, and, frankly, less civil.

Reddit, for example, provides fertile ground for misogynistic activism to flourish. Highly liked content (including links and comments) ranks higher on the site’s homepage, which in turn attracts more attention—effectively amplifying the hate crowd (Massanari, 2017). As we saw in Zheng’s case, a single vicious comment gained 2,000 likes overnight. The algorithm has no morals; it simply pushes traffic, whether positive or negative. Thus, a single hateful comment may be exposed, which in turn attracts more trolls to join the attack. It’s a vicious cycle: Hate breeds attention, which breeds more hate.

Hate breeds attention, which breeds more hate

The real fight isn’t just online — it’s cultural, legal and personal

If so many people are aware of this problem, why haven’t we solved it yet? In fact, combating online hate is a complex challenge. Part of the difficulty is who is responsible: Should the platforms do more to police content? Should the government introduce tougher laws? Or should we, the users, remain silent? The answer is all of the above—but historically, each side has failed in different ways.

Social media platforms have long taken a hands-off approach. They often take action only after tragedy or public outcry. In Zheng’s case, the abusive post was left unanswered for days even though it had thousands of likes. The platforms claim to support free speech but are inconsistent in enforcing their policies—quick to remove copyrighted music but slow to act on hate speech (Bowcott, 2017). While tools like AI moderation and user reporting systems have improved, they still have a lot missing. Human reviewers can’t possibly review the sheer volume of posts, algorithms can’t understand context, and trolls know how to game the system.

More importantly, there is a lack of will from platform leadership. Frances Haugen, a former Facebook employee, revealed that the company knew how to reduce hate and misinformation but chose not to do so—because lower engagement meant lower profits (Paul & Milmo, 2021). When profits outweigh people, real progress stalls.

Most anti-harassment laws were written before the digital age and don’t apply to situations like anonymous group attacks. Jurisdiction is another vexing issue—what law applies when someone in one country attacks someone in another country through a platform in a third country? In response, Australia introduced the Online Safety Act 2021, which established an Online Safety Commissioner with the power to issue takedown notices for online abuse against adults (not just minors), and gave authorities the power to require the removal of offending platforms and impose fines (Sinpeng et al., 2021). This is significant—it treats platforms not just as neutral conduits, but as service providers responsible for user safety.

But perhaps the most powerful support comes from us. Hate thrives in silence. Many people engage in online violence not out of malice, but because “everyone else is doing it.” Changing this means changing the culture: being more empathetic, calling out hate when we see it, and supporting victims. Campaigns like China’s #PinkInnocence show that solidarity is far more powerful than trolls.

The pink-haired girl didn’t deserve to die. No one should be subjected to online abuse for something so trivial. No one should be driven to death for speaking out, as Sulli did, or face death threats for speaking out, as Nina did. The experiences of these women have opened the eyes of many to the reality of online gender hate. The outrage and sympathy people feel for this needs to be translated into sustained action. That means pushing social media companies to improve, supporting sensible legislation to protect online users, and each of us taking a stand in our own online lives.

The internet can be better. After all, it’s just a mirror of human nature – if we don’t like the ugly reflection we see, we have to change it. It’s up to each of us to ensure that social media is a platform for communication, not a weapon of attack. Let’s make sure these tragedies don’t happen in vain, and that the pink-haired girl – and all women who express themselves online – can do so safely without facing a torrent of hate. It’s going to take a concerted effort, but it’s definitely worth it to prevent the next real-life tragedy caused by online hate.

Reference

Bowcott, O. (2017, November 28). Social media firms must face heavy fines over extremist content – MPs. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2017/may/01/social-media-firms-should-be-fined-for-extremist-content-say-mps-google-youtube-facebook

Ge X. (2020). Social media reduce users’ moral sensitivity: Online shaming as a possible consequence. Aggressive behavior, 46(5), 359–369. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21904

Massanari, A. (2017). Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures. New Media & Society, 19(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815608807

Matsuda, M. J. (1993). Public response to racist speech: Considering the victim’s story. In M. J. Matsuda, C. R. Lawrence III, R. Delgado, & K. W. Crenshaw (Eds.), Words that wound: Critical race theory, assaultive speech, and the First Amendment (pp. 17–51). Westview Press.

Paul, K., & Milmo, D. (2021, October 4). Facebook putting profit before public good, says whistleblower Frances Haugen. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/oct/03/former-facebook-employee-frances-haugen-identifies-herself-as-whistleblower#:~:text=Referring%20to%20the%20algorithm%20change%2C,will%20make%20less%20money.%E2%80%9D

Shin, H., & Yi, H. Y. (2019). K-pop singer decries cyber bullying after death of ‘activist’ star Sulli. Reuters

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F. R., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021). Facebook: Regulating hate speech in the Asia pacific. Facebook Content Policy Research on Social Media Award: Regulating Hate Speech in the Asia Pacific.

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F. R., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021). Facebook: Regulating Hate Speech in the Asia Pacific. Department of Media and Communications, The University of Sydney. https://hdl.handle.net/2123/25116.3

The Economist Intelligence Unit. (2021, March 1). Measuring the prevalence of online violence against women. THE ECONOMIST INTELLIGENCE UNIT. Retrieved April 13, 2025, from https://onlineviolencewomen.eiu.com/

Tone, S. (2023, March 2). To fight trolls, a campaign wants people to flaunt pink hair. #SixthTone. https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1012338

Be the first to comment