I believe that everyone has had the experience of signing into a new website or application, often scrolling to the bottom of a privacy policy and Terms and Conditions, clicking “I Agree” without reading them carefully, and quickly moving on. Such behavior may seem harmless and like a time-saver, but in fact, it hides many terms we’d never agree to. It means that this small action actually opens the door for platforms to collect, profile, and profit from our personal data which we never intended to share.

To picture this:

A user signs up for a new app and is faced with a wall of legal and policy text which is sometimes over 5,000 words long. They cannot enjoy the service unless they tick the box to agree to the Privacy Policy and Terms and Conditions. Therefore, the reality is that very few people actually read what they are agreeing to.

Did you know?

A Pew Research study found that while 97% of Americans say they are regularly asked to approve privacy policies, 74% say they rarely or never read them at all (Auxier et al., 2019, p. 6). Another study showed that if an average user were to read every privacy policy they encounter in a year, it would take around 244 hours—roughly 40 minutes per day (McDonald & Cranor, 2008, p. 563). These data reflect that most users, consent is something they click, not something they actually think about.

As Suzor (2019) argues, Terms of Service documents aren’t written to help us make informed decisions—they’re designed to serve the platform’s legal and protect business interests. (pp. 10-11).

This raises a key question: is this really consent, or just the option they want us to take?

2. Click, Consent… Tricked? How platform design shapes our choices

Most users think they’re in control—but are they? When apps make us click through thousand-word policies just to sign up, are we truly consenting, or just be illusioned?

Here’s something surprising:

Based on my own experience and observations of the people around me, I found that people usually spend only a few seconds on privacy policy pop-ups. Most of them didn’t even notice terms that said their data may be sold to third parties.

Design plays a big role. Platforms often hide important choices deep in complex settings, use small fonts, or default to maximum tracking. Such design tricks that guide users toward the decisions companies want reflect a broader governance issue that Suzor (2019) highlights: platforms often design their systems in ways that give the appearance of user agency while retaining full control over decision-making processes. In his research, terms of service function as private law—they are not negotiated, not limited by constitutional rights, and give platforms almost absolute discretion to decide how rules are made and enforced (pp. 10–13).

So, in theory, we agree, but in fact, we’re nudged. That’s not free choice. That’s manipulation dressed as consent.

3. Behind the €310M Fine: How LinkedIn took away real choice

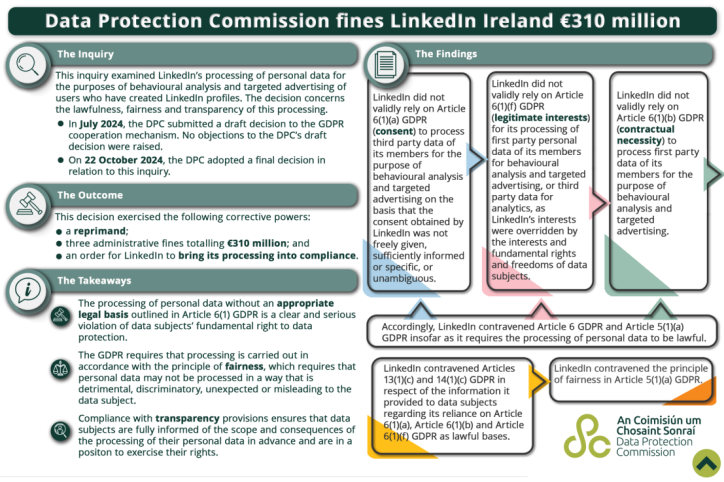

One of the typical examples of deceptive and misleading consent in action is LinkedIn. The Irish Data Protection Commission (DPC) fined LinkedIn Ireland €310 million for violating multiple sections of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) on October 24, 2024. That is, LinkedIn was found to have processed personal data for behavioral analysis and targeted advertising without any valid legal basis. To be more specific, the platform violated GDPR Article 6(1) (lawfulness), Article 5(1)(a) (fairness), and Articles 13 and 14 (transparency), because the consent obtained was not freely given, specific, unambiguous or sufficiently informed (Irish Data Protection Commission, 2024).

The case is was initiated following a complaint by the French nonprofit La Quadrature du Net, revealing LinkedIn’s lawless and unfair issues: it combined first-party data (user-submitted profiles) with third-party signals to target advertisements and analyze user behavior and preferences without offering a clear and accessible opt-out option. Instead, the option to refuse tracking were always hidden deep in complex settings or bundled under some vague terms. As DPC Deputy Commissioner Graham Doyle said that when a platform processing of personal data without an appropriate legal basis is “a clear and serious violation” of people’s fundamental rights and it created an unfair dynamic in which users had no practical ability to say “no”.

While LinkedIn technically offered “choices,” these were structured to encourage agreement. This matches what Suzor (2019) describes as a privatized governance model where Terms of Service operate as one-sided instruments of control. Rather than support informed consent, they function as legal shields for practices users neither understand nor meaningfully authorize. Suzor emphasizes that platforms often appear to offer autonomy through customizable interfaces, but actually design the underlying structure to preserve corporate control over user data and interaction norms (p. 13)

This is not just a bad design—it is a deliberate structuring of power relations between users and platforms. Platforms like LinkedIn appear lawful (offering a “privacy center”) while making it basically impossible to refuse in any real way. It feels like playing a game where the platform made the rules, and you are told you can choose—but only between options they have ordered for you.

4. Pay or Be Tracked: Meta’s new way to sell privacy

LinkedIn isn’t the only platform reshaping consent, Meta does it more directly. Meta has gone for a bolder strategy—forcing users into a trade.

What’s happening?

In 2023, Meta introduced a subscription model in the EU: users could pay €9.99 a month to avoid the ads, or use the platform for free by agreeing to full tracking. On July 1, 2024, the European Commission published preliminary findings under the Digital Markets Act (DMA), warning that this model may violate Article 5(2), which requires that consent be freely given and accompanied by a meaningful alternative (European Commission, 2024, paras. 2–4). Because Meta didn’t offer a third option—a free version without surveillance, it means users were forced to pick between paying or giving up their privacy. As Commissioner Thierry Breton put it, the DMA is meant to “give back to the users the power to decide how their data is used”—not to let platforms build pressure-based consent systems (European Commission, 2024, para. 10).

Real-world impact:

In early 2024, Meta began consulting with UK regulators about a similar “consent-or-pay” scheme. The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) pushed back, warning that such models must meet strict legal and ethical tests—just showing a pop-up isn’t enough (Information Commissioner’s Office, 2024).

So, is Meta worse than LinkedIn? I am afraid not necessarily. Meta is more transparent—LinkedIn hides its tracking and design vague defaults. But both use their platform power to limit what users can decide.

5. Why LinkedIn makes privacy feel like a trap

If platforms are built to make it seem like we’re saying yes—like Suzor (2019) says—it’s not real choice. And as Nissenbaum (2010) shows, once we click “agree,” our data can be used in ways we never imagined. (p. 841)

5.1 Privacy isn’t about hiding—it’s about staying in context

When you upload your resume to LinkedIn, you certainly want the recruiter to see it instead of an advertisement firm or other agency, but this expectation sometimes doesn’t end well.

Helen Nissenbaum (2010) calls this principle contextual integrity. It means Information flows should align with the informational norms of a given social context. Put simply, people expect their data to be used in ways that make sense within the situation where they shared it. (p. 850). So a resume submitted for job searching shouldn’t be used as an ad profile or for other commercial purposes.

As she said, when platforms themselves decide what counts as “normal” behavior to use data, they will erase the meaning behind your choices (Nissenbaum, 2010, p. 8). A job title update may cause financial ads to appear (Nissenbaum, 2010, p. 7). A skill listing like “Python” becomes a signal for job-hopping predictions.

These shifts hide behind vague policies and default settings (Nissenbaum, 2010, p. 16). So, as a result, users may face risk without realizing it. It’s not just about privacy—it’s about trust.

5.2 LinkedIn’s three hidden violations

These isn’t just theoretical, and here’s how LinkedIn abused their power on data:

•Repurposing tags: Adding a skill like “Python” might flag you as a future job-hopper, triggering targeted financial ads.

•Third-party sharing: Your behavior is sent to analytics firms under vague terms like “service improvement”, not just to recruiters.

•Predictive monitor : Internal models guess when you’re likely to quit. Sometimes user’s resignation risk was shared with their boss without permission

They are signs of a system that repurposes your professional identity behind your back lawlessly.

5.3 What Can We Do Now?

Policy response:

Laws like the EU’s Digital Services Act should be considered. Data shared for hiring must not be sold or reused for unrelated profiling.

User action:

Take a moment to check your LinkedIn privacy settings and turn off options like “research and product improvement”. It won’t solve everything, but every little step helps protect your data.

If privacy depends on context, then platforms must stop changing the context without permission; it has to be more transparent because users have the power to see and shape where the boundaries lie.

6. When the terms rule over the user: power structures in design

Most people think they’re using a service. In reality, they’re following invisible rules. Platforms write Terms of Service that controls what users can do, how their data is used, and even what speech stays online.But unlike laws published by governments, these terms are written by platforms, and the terms sometimes change without warning.(Suzor, 2019, p. 13)

Terry Flew (2021) calls this platform governance—when tech companies behave like private regulators, making their own systems of rules (pp. 72–75). He outlines a “governance triangle”: ideally, platforms share power with governments and civil society (p. 73). But in practice, platforms dominate while regulators do not participate in time and users are excluded.

(Terry Flew, 2021)

Problem:

Platforms guide us with designed options and default settings collect maximum data and Opt-outs are hard to find. Interfaces seem fair—but they’re not.

Flew (2021) calls this the “logic of governance without government”—a system that appears neutral but tilts toward corporate control (p. 81).

Nissenbaum (2010) reminds us: privacy relies on contextual integrity—data should flow in ways users expect (p. 840). When Terms of Service secretly allows data repurposing, the expectation will being against. Platforms use agreement boxes to rewrite norms, however, users rarely notice and realize it.

So even we think we are choosing freely, we are often just picking from options that were designed to serve the platform, not really by ourselves.

7. Who’s responsible for fixing this?

When platforms quietly reshape how consent works, the obvious question becomes: who should stop them?

Governments?

In theory, yes. But regulation is often too slow to catch up with fast-moving tech. Even GDPR—a landmark privacy law, also has its limits. Meta’s “pay-or-consent” model arguably meets the legal requirement of consent, but it fails the ethical test and not accepted by the public..

Platforms themselves?

Some companies set up ethics boards or publish transparency reports. But critics argue this is often just PR. Take Facebook’s Oversight Board: it reviews content decisions, not data practices. It’s a self-contained system where the moderator works for the platforms.

Users?

We are told to “check settings completely” or “read the policy carefully.” As Flew (2021) argues, relying on individuals rather than states to hold platforms accountable is unrealistic and shifts responsibility away from structural solutions (p. 142). That’s not the real empowerment.

What’s needed is shared responsibility together. Stronger regulation, real enforcement, and platforms designed to put users first, not profit from their data.

8. Consent shouldn’t be a shortcut for control

Right now, it means whatever the platform wants. Click “Agree” or get locked out. Scroll past thousands words, then lose your privacy in little seconds. This isn’t real choice. Although Suzor (2019) does not use the phrase “illusion of consent,” he critiques how platforms design lawlessness that simulate agreement without supporting real understanding or autonomy. (pp. 11–14)

When consent loses meaning, so does autonomy.

Here’s what I expect real consent to look like:

• Understandable: Policies written in plain language, not legalese.

• Optional: You should be able to say no without losing access.

• Restricted: Your data should only be used for the purpose you agreed to.

It’s time to stop pretending that clicking “I Agree” means anything.

We don’t need longer policies. We need better rules and a right for everyone.

Word count: 2129

Reference

Almond, S. (2024, August 15). ICO statement on Meta’s ad-free subscription service. Ico.org.uk; ICO. https://ico.org.uk/about-the-ico/media-centre/news-and-blogs/2024/08/ico-statement-on-metas-ad-free-subscription-service

ap news. (2024, October 24). LinkedIn Hit with 310 Million Euro Fine for Data Privacy Violations from Irish Watchdog. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/linkedin-microsoft-privacy-european-union-ireland-6769ae3b83ea0d83cab8d8cfd1fa7e68

Auxier, B., Rainie, L., Anderson, M., Perrin, A., Kumar, M., & Turner, E. (2019, November 15). Americans and Privacy: Concerned, Confused and Feeling Lack of Control over Their Personal Information. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/11/15/americans-and-privacy-concerned-confused-and-feeling-lack-of-control-over-their-personal-information/

Brussels . (2024, July 1). Press corner. European Commission – European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_3582

Data Protection Commission. (2024, October 24). Data Protection Commission. https://www.dataprotection.ie/en/news-media/press-releases/irish-data-protection-commission-fines-linkedin-ireland-eu310-million

European Commission. (2024, July 1). Commission sends preliminary findings to Meta over its “pay or consent” model for breach of the Digital Markets Act. https://digital-markets-act.ec.europa.eu/commission-sends-preliminary-findings-meta-over-its-pay-or-consent-model-breach-digital-markets-act-2024-07-01_en

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms . Polity Press.

Information Commissioner’s Office. (2024, August). ICO statement on Meta’s ad-free subscription service. https://ico.org.uk/about-the-ico/media-centre/news-and-blogs/2024/08/ico-statement-on-metas-ad-free-subscription-service/

Mcdonald, A., & Cranor, L. (2001). The Cost of Reading Privacy Policies (p. 183). https://kb.osu.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/a9510be5-b51e-526d-aea3-8e9636bc00cd/content

McMahon, L. (2025, March 24). Meta considers charging for Facebook and Instagram in the UK. BCC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c0kglle0p3vo

Nissenbaum, H. (2018). Respecting Context to Protect Privacy: Why Meaning Matters. Science and Engineering Ethics, 24(3), 831–852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-015-9674-9

Suzor, N. P. (2019). Lawless: The Secret Rules That Govern Our Digital Lives. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108666428

Be the first to comment