Introduction

Through the Gates of Digital Illusion

A few months ago, a photo of a “purple apple” burst onto Facebook. This fruit was a dreamy shade of violet, growing from the inside out, as perfect as if it came from a fairy tale (Wazer, 2024). Some people even headed to the local market in search of it but found nothing. The truth? The apple didn’t exist. It was an artificial illusion, conjured entirely by AI.

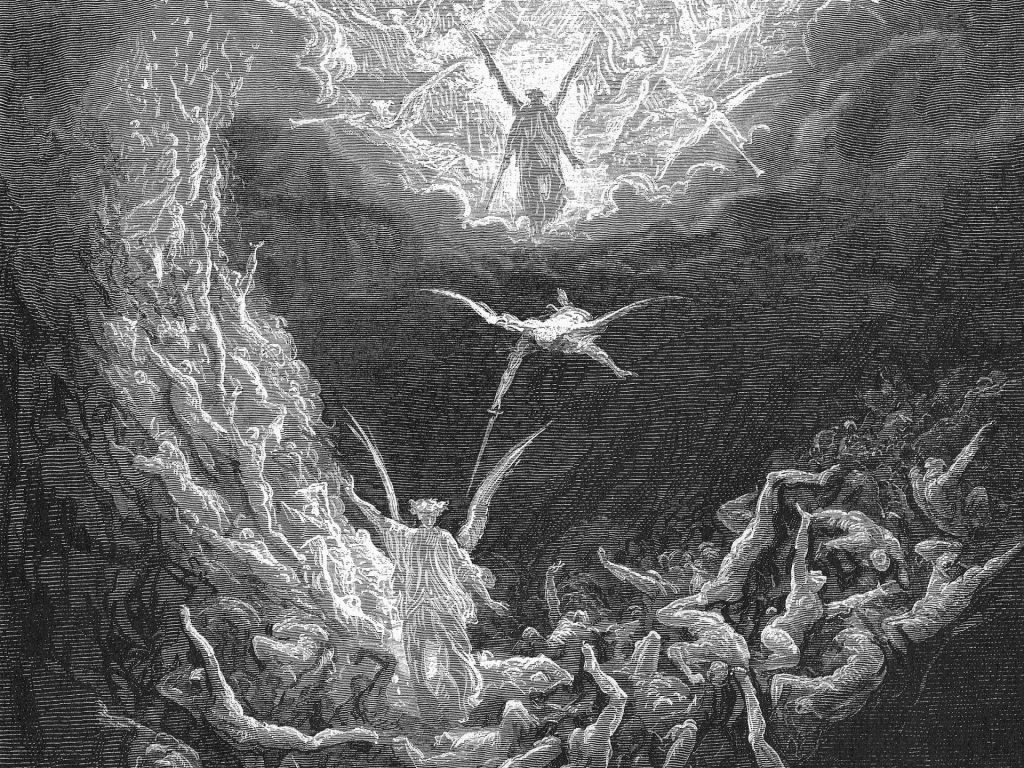

But the purple apple wasn’t an isolated case. It was a signal, a warning that we’ve already stepped through the gates of digital illusion. Just like the inscription above the gates of Dante’s Inferno:

” Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.”

The Deceptive Aesthetics of Images

When Nature Becomes an Algorithmic Illusion

As the French poet Baudelaire showed throughout Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flower of Evil), evil does not merely exist—it blooms, often with a beauty more seductive than virtue. Today AI gives us a new bouquet: evil flowers, blooming in pixels.

The charm of AI-generated images of plants and animals comes inexactly from its betrayal of nature. Whether it’s color, form or habitat, they don’t care about the logic of growth in nature, they are not bound by genetics, and don’t need to follow the rules of the ecosystem. With just a few bits of descriptors text, AI can generate a flower—forever blooming in pixels.

Type in a few keywords, such as “aurora rose” or “dreamlike garden” on platforms like Instagram, Rednote and Pinterest, and the AI algorithms instantly help you find various images. These images are intensely colorful, perfectly composed, and have almost all the attractable elements that capture the public’s attention without any caption.

These AI-generated images of plants and animals aren’t just “too pretty to be real”, they are rewriting the way we perceive nature itself. This rewriting doesn’t through argument or education; it directly targets one of our most basic cognition sense: visual. In the age of information overload, we’ve been trained to trust what we see. It has been shown that people tend to fixate longer on faces that look trustworthy, even without evidence. This shows how trust can be triggered, not logically earned (Wu et al., 2022). On image-driven platforms, AI-generated visuals tap directly into this instinct—appearing real is enough.

Platform algorithms are more than happy to push these polished illusions straight to users’ screens. In this economy driven by clicks and shares, the more eye-catching an image is, the more likely it is to be liked, shared, and commented on—prompting the algorithm to recommend it even more. The result is a self-enhancement loop.

We no longer ask, “Is this real?” We scroll, double-click, we share, but rarely pause to question the image in front of us.

This is not only a misreading of nature, but a colonization and hegemony in the cultural sense. The irony of it all is that we are embracing the illusion—willingly. We share it in group chats, present it in classrooms, and print it on product packaging. We pass along a version of “nature” which never truly belonged to this world. We haven’t committed any clear sin—yet we linger outside the realm of truth. AI-generated image is building its own limbo: a glowing edge of hell made of visual pleasure, where we lose ourselves and forget that the truth lies further ahead.

When Illusion Replaces Knowledge

The Collapse of Knowledge Under Visual Hegemony

AI-generated images don’t just fool the eye, they quietly reshape our basic ability to judge what we know about nature. We no longer just appreciate “pretty pictures” but are replacing knowledge with illusion.

Have you ever come across online shops selling flower seeds with unbelievably beautiful images on their product pages? Some online scams are now using AI-generated images of plants that don’t exist, such as “black bleeding hearts”, to trick buyers into purchasing fake seeds and giving up personal information. Buyers may receive seeds that won’t sprout, sawdust, or even be invasive, and more seriously, risk exposing their personal data and facing financial consequences (Colonial Gardens, n.d.).

More worryingly, even some formal scientific studies have been polluted. Generative AI is now being used to fabricate scientific images, posing a serious threat to the integrity and credibility of academic publishing (Gu et al., 2022). AI-generated images and videos, which are always highly realistic, can be used to spread disinformation, posing a serious threat to the credibility of ecological science. Fabricated visuals of environmental events or species may mislead the public and influence policy decisions. At the same time, researchers may exploit such technologies to falsify data, undermining the integrity and reliability of scientific research itself (Rilling et al., 2024).

These examples show that AI-generated images are not only visual illusions but also knowledge deceptions. Unlike academic errors that are easily corrected by experts, these images spread at high speed, quoted and shared as truth by countless users. Social media then enlarges them in an endless loop, gradually building what looks like visual knowledge.

The Self-Reinforcing Loop of AI Imagery

The Source is Gone, But Images Keep Replicating Images.

One of the biggest dangers of AI-generated images is that it’s creating a self-reinforcing loop of information pollution. As AI-generated content spreads across the Internet, this synthetic data is indiscriminately collected and fed back into training datasets. The original training mechanisms that relied on real human-made data are breaking down. Recursive training on AI-generated outputs has been shown to cause distributional drift and model collapse (Xing et al., 2025). In the end, AI feeds on its own illusions, pushing reality further away, and slowly fading from view.

This mechanism is like a snake devouring its own tail—a true ouroboros. AI systems are consuming the content which they create, caught in cycles of self-reference and self-confirmation. As real-world images and data become rare, synthetic content takes up more and more space, gradually polluting entire image databases.

A practical example is that several open-source image datasets have incorporated large numbers of trending social media images, often without filtering, and put them into AI training models. Many of these images appear to be “nature photography” but are generated by users with tools like Midjourney or Stable Diffusion. As a result, AI models learn to treat these fictional plants as real during training and then generate even more images with similar styles and structures. These then mislead the next wave of users and even enter commercial image libraries and search engine recommendation systems.

Even more troubling: this kind of pollution is unsupervised. Unlike academic publishing, there’s no peer review for AI-generated images. Their spread and reuse require no oversight, no proof—just clicks. One click to generate. One click to distribute. One click to absorb. In the end, every illusion flowers logically back into the system that made it and is ready to deceive again.

The consequence of self-contamination information pollution is that AI’s understanding of the world is becoming more and more narrow. It no longer learns from reality, it just repeats its outputs, layer after layer. And this narrowing affects us too: the “nature”, “animals”, and “plants” we now see increasingly come from these illusions, born of repetition rather than reality.

In the end, what we face may not be an increasingly powerful AI, but a chimera: the monster which drifts further from reality, pasted up with disparate elements. An unnatural species, algorithmically sculpted and shaped by patterns that ignore nature itself.

We’ve seen AI-generated images appear in official accounts more than once, and in some places, they’re even used as promotional material. This mechanism of visual pollution has already spread beyond art, science communication, and advertising, seeping into education, journalism, and public information systems. AI is now consuming the fake images it created, refining them into smoother, more attractive versions, then sending them back to us as if they were textbooks about the real world.

This isn’t technological progress; it’s a perceptual loop. We may no longer be able to identify which images come from the world, and which are just rhapsodies born of the machine.

Drunk on Visual Illusion

From Dionysus to the New Gods of Digital Illusion

The real danger of AI-generated images isn’t that they look real; it’s that they offer an illusion more comforting than reality itself. A visual pleasure that we don’t just believe it—we prefer it.

The philosopher Nietzsche once used the “spirit of Dionysus” to describe the pursuit of sensory explosion, emotional release and ecstatic surrender. It represents the raw eruption of human instinct and a rebellion against the rational of the world. Today, AI-generated imagery has become the Dionysus of our time. It doesn’t provide information, it doesn’t summon thought, it simply delivers beauty, engineered for addiction.

In Rednote, the keyword #healing-style illustrations has garnered over 1.95 billion views. More than half of them is generated from AI, yet a significant part of them is not labeled as such. The keyword #AICG has also received more than 1.3 billion views, which shows that a large number of users are consuming the illusion without realizing it.

Platform algorithms know this as well. Their recommendation systems tend to favor content with high shares and likes, and AI-generated visuals fit perfectly into this pleasure-driven logic. An article by United Press International (UPI) on April 24, 2024, noted that AI-generated images are becoming increasingly common and popular on social media. These visuals are often used to attract user engagement, and platform algorithms may naturally choose to boost such posts as a result (DiResta et al., 2024). As some researchers have observed, platforms don’t just connect users, they shape what users see and believe. Through trust-building mechanisms, community-driven curations, and platform-based ecosystems, they actively construct perception loops (Parker et al., 2016).

AI-generated images are no longer tools for information, they’ve become factories of visual pleasure. They are more like digital alcohol, which is dripped into users’ eyeballs by algorithms. One picture after another, one dream after another, until rationality gradually numbed, and judgment slowly fades.

We weren’t deceived. Instead, we brewed the drink ourselves and raised the glass willingly.

This is the Dionysian spirit of the digital age: it’s not that illusion has defeated reality; it’s that we no longer need reality at all.

The Age of Willing Sacrifice

On the Altar Lies Reality, Not the Lamb

As we engage with AI-generated images, we are participating in a ritual—one of sacrifice, silent and unseen.

The algorithm is not a god—but it has mastered the tone of a god. It doesn’t command us to believe; instead, it teaches us to stop questioning. We don’t obey out of fear, but out of visual pleasure. One illusion after another is hailed as a “new possibility of nature”, more and more fakes are celebrated as the “premium version of reality”. And in this process, what we sacrifice is not flesh and blood, but our ability to identify truth from falsehood and endure complexity.

Abraham once bound his son upon the mountain, ready to offer him to an unseen god. Today, we bind real nature, real perception, and real experience to the altar of illusion, and say “That’s a nice picture” while severing our last ties to reality.

This time, will there be an angel to stop us?

Conclusion: Waking from the Illusion

Dante travelled through the nine circles of Inferno and climbed the seven terraces of Purgatorio before he could glimpse the true light. Today, we may be journeying through our own inferno of images. But unlike Dante, we’re not suffering, we’re enjoying it. The illusion wraps around us like a velvet blanket, dulling our senses and softening our judgment. AI-generated images don’t force us to be addicted to them; they just simply, quietly and accurately deliver illusions that look real, but feel better than real. And slowly, we learn to stop asking questions.

In the digital age, what we need to fear most may not be fake images, but our addiction to falsehood.

Eden is gone, but at the very least, we can walk out of the illusion. It cannot be denied that AI-generated images have brought us too much convenience. Internet governance takes time, and we cannot expect platforms to stop recommending AI visuals immediately, nor can we change the public’s visual preferences.

—But we can choose to open our eyes.

Reference

Colonial Gardens. (n.d.). The hidden dangers of AI plants. https://colonialgardenspa.com/the-hidden-dangers-of-ai-plants/

DiResta, R., Reddy, A., & Goldstein, J. A. (2024, April 24). Artificial AI-generated images draw in social media users. UPI. https://www.upi.com/Voices/2024/04/24/artificial-intelligence-generated-images-social-media/6141713964302

Gu, J., Wang, X., Li, C., Zhao, J., Fu, W., Liang, G., & Qiu, J. (2022). AI-enabled image fraud in scientific publications. Patterns, 3, Article 100511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2022.100511

Parker, G. (2016). How platforms attract users. In G. Parker, M. Van Alstyne, & S. P. Choudary, Platform revolution: How networked markets are transforming the economy and how to make them work for you (pp. 60–78). W. W. Norton & Company.

Rillig, M. C., Mansour, I., Hempel, S., Bi, M., König-Ries, B., & Kasirzadeh, A. (2024). How widespread use of generative AI for images and video can affect the environment and the science of ecology. Ecology Letters, 27(3), e14397. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.14397

Wazer, C. (2024, September 27). Fact check: Photo of purple apples from Saskatchewan are fake. Yahoo News. https://tech.yahoo.com/general/articles/fact-check-photo-purple-apples-020000212.html

Wu, J., Li, J., & Yuan, H. (2022). The visual characteristics of the Chinese older adults in facial trustworthiness processing: The evidence from an eye movement study. Advances in Psychology, 12(3), 792–802. https://doi.org/10.12677/AP.2022.123094

Xing, X., Shi, F., Huang, J., Wu, Y., Nan, Y., Zhang, S., Fang, Y., Roberts, M., Schönlieb, C.-B., Del Ser, J., & Yang, G. (2025). On the caveats of AI autophagy. Nature Machine Intelligence, 7, 172–180. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-025-00984-1

Be the first to comment