Introduction

In today’s digital space, countless hate speech is rampant on media platforms. You may have noticed: Despite announcing many regulations, why are there still a lot of hate speech on the media platforms we use? In fact, “freedom of speech” has gradually become a convenient excuse for some platforms to evade regulatory responsibilities. Some social media companies, faced with the proliferation of hate speech, false information, and extremist content, often use the pretext of upholding “freedom of speech” to allow this information to ferment and create more traffic. This strategy not only blurs the boundaries of freedom of speech, but also causes social harm in reality. Perhaps you have realized that ordinary users and society are bearing increasingly serious costs, and it is urgent to stop the negative phenomenon of platform governance. This article will delve into the motivations, social costs, and policy challenges behind social media companies using the “freedom of speech” narrative to cover up their governance failures.

Freedom of speech or governance irresponsibility? How X platform abandons responsibility in the name of ‘freedom’

In the practice of content governance on contemporary digital platforms, there has always been a structural contradiction: how to pursue economic benefits while assuming social responsibility.

On the one hand, this complex situation is reflected in the economic burden of governance costs. In order to effectively curb hate speech, false information, and extremist content, platforms have to invest a large amount of manpower, material resources, and advanced technological resources to improve the accuracy and efficiency of content review. However, even with such a high-cost investment, there are obvious limitations to the technological means themselves – algorithmic automated audit systems are prone to generating a large number of false positives, while human auditors face problems of insufficient efficiency.

On the other hand, while implementing strict content review measures, platforms have to consider feedback from users and the market. Overly strict review mechanisms may reduce the browsing volume of platform content, leading to a decrease in benefits. However, controversial or provocative content often attracts people’s attention, which can help the platform gain more traffic. ““Unfortunately, outrage and hostility tend to drive engagement,” Said UC Davis communication professor Cuihua (Cindy)Shen, “The more people interact with extreme content, the more it gets promoted.”(Dioum, 2025). In such a situation, if the platform intervenes excessively in content governance, it may directly affect the platform’s own economic interests.

The governance changes carried out by X platform (formerly Twitter) after Elon Musk took over are a typical manifestation of this logic. Since Musk’s acquisition of the platform for $44 billion in October 2022, his team has quickly implemented reform measures aimed at expanding freedom of speech (Perrino, 2022). This includes the large-scale restoration of user accounts that were previously banned for posting hate speech, false information, or inflammatory remarks, such as Kanye West (Ye), who has publicly posted a series of anti-Semitic tweets on Twitter (Furdyk, 2023). Musk once publicly stated, ‘I am an absolute advocate of freedom of speech.’ (Musk, 2022). This bold reform towards pure freedom of speech quickly weakened the original review mechanism of X platform, and allowed the growth of hate speech.

Figure 2 Adidas terminates relationship with Kanye West amid antisemitic remarks (NBC News, 2022).

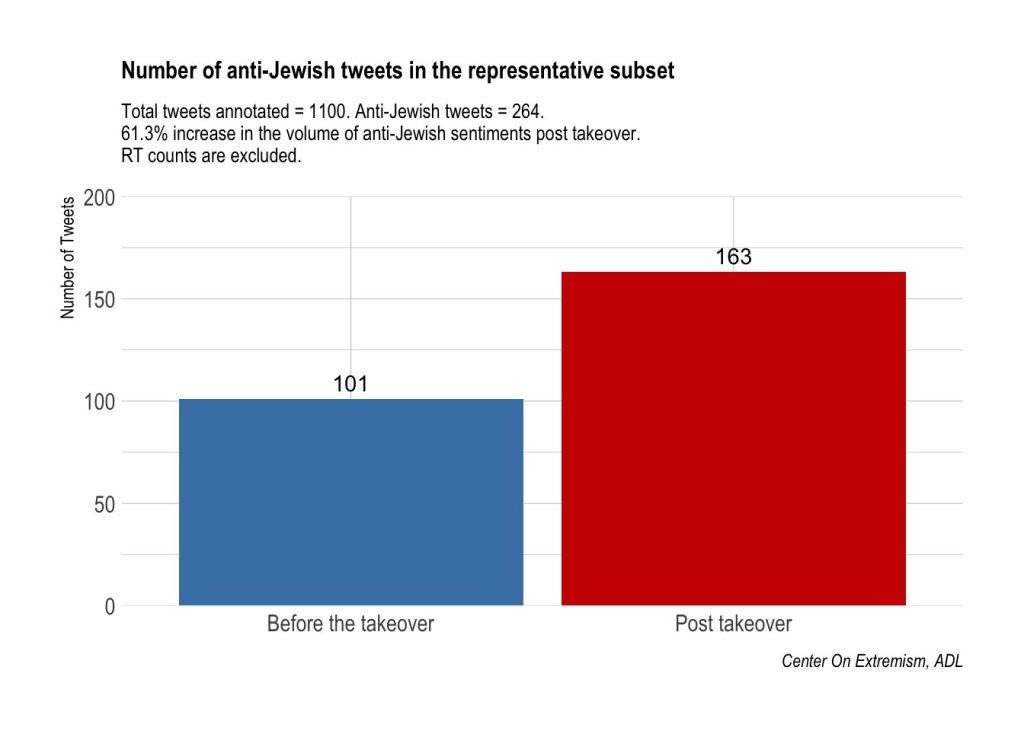

According to statistics from the Anti Defamation League (ADL) in the United States, there has been a significant increase in anti-Semitic and racist content since Musk took over, with hate posts in some categories growing by over 60% (ADL, 2022). The interaction volume of hate content has also reached a historical high, reflecting its greater diffusion power under algorithm push. In addition, studies have shown that anti Muslim hate speech related to the Brexit referendum on platform X is heavily concentrated among a few specific user groups. About 50% of the relevant content comes from only 6% of users, most of whom explicitly state their “anti Islamic” identity (Williams, 2019). This phenomenon indicates that the platform’s laissez faire deregulation can easily lead to excessive traffic for inflammatory language, including hate speech.

Figure 3 Findings indicate a 61.3% increase in the volume of tweets referencing “Jews” or “Judaism” with an antisemitic (Anti-Defamation League, 2022).

Returning to the question we raised: Why do platforms like to ignore hate speech? The answer is obvious. Faced with the dilemma of balancing social responsibility and economic benefits, some social media platforms have begun to reduce or even avoid the cost and burden of content censorship under the guise of “free speech”. This strategy has actually become an effective but problematic business model, driving digital platforms to gradually transform the principle of freedom of speech into a shield for governance loss and social risk expansion.

Why is the abuse of ‘free speech’ so dangerous: From X platform to real-life violence

As a member of the Internet era, every social media participant should be soberly aware that we are in a digital environment where harmful information continues to spread, exacerbated by the lack of platform governance. As the creators of cyberspace rules, social platforms should bear the public responsibility for content regulation and spatial governance, but the current situation is contrary to this. As digital governance scholar Tarleton Gillespie pointed out, although platforms claim to be “neutral technology intermediaries,” in essence they selectively control the process of information transmission (Gillespie, 2018). They are not unable to govern, but selectively give up governance, turning a blind eye to allow malicious content to ferment in the gray areas of platform rules, in order to earn popularity and traffic. It is not difficult to imagine that under the platform economy logic of “traffic growth first”, platform rules will promote the expansion of this gray area. On the surface, they raise the banner of “freedom of speech”, but in reality, they leave a lot of ambiguity in the implementation of supervision. From the perspective of the innocent public, such a trend will lead users to have to accept the platform’s content distribution mechanism to increase the distribution of malicious content. This makes all ordinary users who participate in social media platforms passively involved in a discourse dominated by hatred and confrontation, gradually becoming the “cost bearers” of this commercial manipulation logic.

A case that occurred in Shrewsbury, Merseyside, UK and was related to the spread of speech on X platform provides typical evidence for this logic. A vicious knife attack occurred in a local dance studio, resulting in the death of three young women and multiple injuries (Lawless, 2024). However, after the incident, a large amount of hate messages about insulting the identity of the attackers appeared on the X platform. Multiple unverified user accounts claim that the perpetrator is a Muslim immigrant named ‘Ali Al Shakati’ (Lawless, 2024). Although the British government later confirmed that the person’s identity was unrelated to the incident, the related hate speech was quickly amplified and spread by far right activists, who blamed the incident on Muslim and immigrant groups (Lawless, 2024).

Faced with such sensitive and potentially high-risk information dissemination, X platform did not timely label and restrict the flow, nor did it implement measures such as bans. In fact, as early as 2022, O’Brien and Ortutay reported that Elon Musk’s acquisition of Twitter has continued to reduce the trust and security team responsible for identifying false information, further weakening the platform’s ability to intervene in harmful content (O’Brien & Ortutay, 2022). In this governance model, highly provocative narratives have gained higher visibility and dissemination efficiency due to algorithmic mechanisms. This case of hate speech being based on algorithmic recommendations for wider dissemination reinforces the gap between Musk’s promise that “hate speech will not cause violence” and reality (O’Brien & Ortutay, 2022).

More seriously, the spread of hate speech has caused social unrest offline in a short period of time. According to Adelaja’s report, on the second day after the incident, a large number of protesters gathered in front of a mosque in the Shospot area, and the scene eventually escalated into a police civilian conflict (Adelaja, 2024). This incident highlights the risk of abuse of the concept of “free speech” in platform governance. The way platforms increase controversial traffic is actually evading social responsibility, but shifting the cost of hatred and extreme speech onto society.

Video Hate Speech on Twitter Jumps 500% in First 12 Hours of Elon Musk Takeover: Report, Youtube (NBC News, 2024)

Therefore, when “freedom of speech” is abused by the platform as an excuse to protect the content that can generate traffic, its social impact goes far beyond the Internet field itself. In fact, the indulgence of hate speech may lead to an increase in violent incidents. A study on the relationship between hate crimes and hate speech shows that inflammatory language on social media often indicates the occurrence of hate crimes, with machine learning models predicting up to 64% of hate crimes to be based on such language (Calderón et al., 2024). The inflammatory role of the Internet is not alarmist. Once its incalculable hidden power is activated by hate speech, it will endanger the wider public.

When we hear someone confidently say ‘platforms should guarantee freedom of speech’, perhaps we should ask: Whose freedom is this? Who is bearing the consequences for this freedom? We must face up to the notion of “free speech” advocated by some platforms. If there is no bottom line, it may not release true rational freedom, but rather hostility towards society. The lack of platform governance not only causes the “freedom” in public spaces to deviate from its original intention, but also becomes a de accountable commercial tool.

Who is defining ‘freedom’? The Three-Party Game of Platform, Government, and Public

Faced with a social environment filled with hate speech, false information, and extremist content, the platform only pretends to be helpless: everything we do is to ensure users’ freedom of speech. But reality tells us that there is a complex game between platforms, governments, and users, and simply criticizing the hypocrisy of these platforms cannot remove their so-called shield of protecting free speech.

Firstly, as social media users, the public lacks the right to understand platform mechanisms. Flew pointed out that the complex terms of the platform often provide users with an all or nothing option and do not fully inform them of their true rights (Flew, 2021). They usually do not understand how platforms recommend content through algorithmic distribution mechanisms, nor do they know how platforms decide what can be said and what cannot be said. In other words, the public not only finds it difficult to seek the right to freedom of speech, but also passively becomes involved in all extreme voices amplified by algorithms.

Secondly, after recognizing the essence of the platform’s maintenance of user freedom of speech, we understand that this is the result of the joint drive of algorithmic logic and commercial interests. The goal of the platform is not to create a healthy public space, but to increase user traffic. It has been proven that the most emotionally charged and controversial content, including hate speech, will be tacitly accepted and even prioritized for promotion.

Furthermore, government regulatory agencies face a dilemma when it comes to regulation. On the one hand, they need to prevent online hatred from triggering real-life violence, while on the other hand, they are concerned about bearing the stigma of ‘suppressing freedom of speech’. Overly strict regulatory policies are easily criticized as a censorship system that undermines the legitimacy of democratic institutions. However, overly loose regulation may be seen as tacitly approving the platform’s inaction, leading to more serious hate crimes.

Figure 4 A typewriter with a paper that reads “freedom of speech.” (Winkler, 2022).

Ultimately, in this game of defining ‘freedom’, ‘freedom of speech’ should not and cannot exist in a vacuum. This issue has never been a shield for one party’s interests, but a profound consideration of responsibility and consequences. The case of X has proven that when platforms use “freedom” as an excuse for regulatory inaction, the entire society ultimately pays the bill. Hate speech, false information, and extremist content are spreading in cyberspace, and conflicts in reality are also intensifying. These platforms do not truly embrace ‘free voice’, but distribute specific content to the public through algorithms. What we need is not greater freedom, but clearer boundaries. The real solution is not to give up freedom or blur its boundaries, but to establish a clear, open, and accountable governance structure. We need to hold platforms accountable for their content ecosystem, clarify boundaries in government regulation, and give the public more rights to understand platform mechanisms. Transparent rules, clear accountability, and users’ right to know are necessary to return ‘freedom’ to a harmonious society.

Reference Lists:

Adelaja, T. (2024, July 31). Violent crowd clashes with UK police after young girls killed. Reuters. Retrieved April 13, 2025, from https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/just-little-kids-taylor-swifts-message-after-shocking-uk-stabbings-2024-07-30/

Calderón, C. A., Holgado, P. S., Gómez, J., Barbosa, M., Qi, H., Matilla, A., Amado, P., Guzmán, A., López-Matías, D., & Fernández-Villazala, T. (2024). From online hate speech to offline hate crime: the role of inflammatory language in forecasting violence against migrant and LGBT communities. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03899-1

Dioum, S. (2025, March 4). What explains the increase in online hate speech? UC Davis. https://www.ucdavis.edu/magazine/what-explains-increase-online-hate-speech

Furdyk, B. (2023, July 30). Kanye West’s Twitter account reinstated amid X rebranding, following 7-Month ban over antisemitic remarks – IMDB. IMDb. https://www.imdb.com/news/ni64178103/

Flew, T. (2021). Issues of Concern. In Regulating platforms. Polity Press.

Gillespie, T. (2018). The Myth of the Neutral Platform. In Custodians of the Internet (pp. 24–44). Yale University Press. https://doi.org/10.12987/9780300235029-002

Lawless, J. (2024, August 1). Misinformation fuels tension over UK stabbing attack that killed 3 children | AP News. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/uk-southport-stabbing-online-misinformation-1dcd23b803401416ac94ae458e5c9c06

Musk, E. [@elonmusk]. (2022, March 5). Sunlight is the best disinfectant [Tweet]. X. https://x.com/elonmusk/status/1499976967105433600

O’Brien, M., & Ortutay, B. (2022, November 14). Musk’s latest Twitter cuts: Outsourced content moderators | AP News. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/elon-musk-twitter-inc-technology-misinformation-social-media-a469130efaebc8ed029a647a149c5049

Perrino, N. (2022, December 1). Free speech culture, Elon Musk, and Twitter. The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression. https://www.thefire.org/news/free-speech-culture-elon-musk-and-twitter

Williams, M. (2019, October 12). The connection between online hate speech and real-world hate crime. OUPblog. https://blog.oup.com/2019/10/connection-between-online-hate-speech-real-world-hate-crime/

Appendix

Figure 1

Leung, J. (2021, March 28). People holding white printer paper during daytime [Photograph]. Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/u5qJyk7LLbY

Figure 2

NBC News. (2022, October 25). Adidas terminates relationship with Kanye West amid antisemitic remarks [Photograph]. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/adidas-terminates-relationship-kanye-west-pressure-cut-ties-antisemiti-rcna53847

Figure 3

Anti-Defamation League [@ADL]. (2022, November 19). Findings indicate a 61.3% increase in the volume of tweets (excluding retweets) referencing “Jews” or “Judaism” with an antisemitic [Tweet]. X. https://x.com/ADL/status/1593714819932332034

Figure 4

Winkler, M. (2022, May 25). A typewriter with a paper that reads freedom of speech [Photograph]. Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/a-typewriter-with-a-paper-that-reads-freedom-of-speech-x4-maNU3mdE

Video

NBC News. (2024, July 31). Hate Speech on Twitter Jumps 500% in First 12 Hours of Elon Musk Takeover: Report [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pb8lZ_lOZBQ

Be the first to comment