Introduction: More Than Just Offence—Why Hate Speech Still Demands Urgent Attention

When a public figure makes a controversial statement online, the responses are often split: “It’s just words,” some say, while others call it hate speech. The boundarys between free expression and harmful communication have become increasingly blurred, especially on social media platforms, where millions of users, including influencers and celebrities, can instantly reach a global audience.

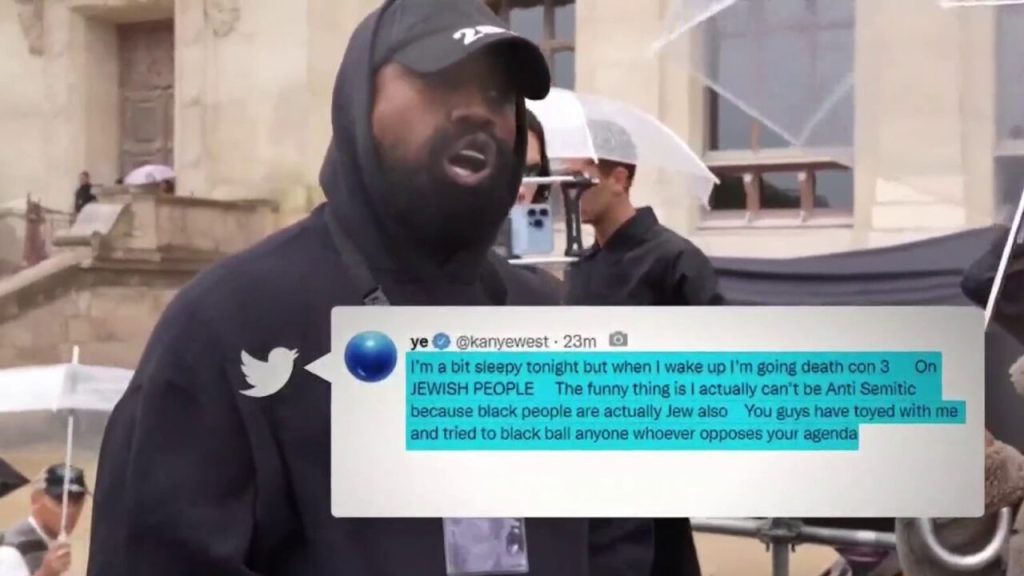

In recent years, rapper and designer Kanye West (also known as Ye) sparked global backlash after making a series of antisemitic statements across multiple platforms. While many saw this as a clear example of hate speech, but others framed it as an exercise of free speech. This was a mixed response from platforms, suspensions, reinstatements, delayed action. This raised the question: what is hate speech, and how should it be handled?

This blog explores hate speech not as a matter of emotional offence, but as a form of structural harmful discursive practice that reinforces existing inequalities and legitimises hostility toward marginalised groups. It argue that digital platforms are failing to adequately address such harm like when it comes from high-profile users whose content is further amplified by algorithms. Using public cases like Kanye West as a reference point, this post unpacks the definition of hate speech, the responsibilities of platforms, and the unintended role of recommendation systems in spreading hate.

1. What Is Hate Speech and Why Is It Harmful?

Hate speech is often misunderstood as merely offensive or rude language. While it can certainly be both, this narrow view overlooks its real power: the ability to reinforce structural inequality and deny groups their rightful place in society. Scholars increasingly argues that hate speech is not about personal feeling, but about systemic impact—about how language shapes hierarchies and creates exclusion.

According to Sinpeng et al. (2021), hate speech should be recognised as speech that causes immediate and long-term harm, and therefore warrants serious policy and governance responses (p. 6). Importantly, hate speech doesn’t need to incite violence directly to be damaging. It can operate through what scholar’s call constitutive harm where the act of speaking itself degrades, silence, and subordinates its targets (Maitra & McGowan, 2012).

Political theorist Bhikhu Parekh (2012) offers a helpful lens defining hate speech as expression that targets identifiable individuals or groups based on irrelevant characteristics like race or religion then “marks them as undesirable and a legitimate object of hostility” (pp. 40–41). In this framework, hate speech is not simply about what is said, but what its effect on the social and political standing of the target group.

Take Kanye West’s public comments, for example. His statements—ranging from threatening language toward Jewish people to praise for historical figures associated with mass atrocities—functioned as more than isolated “opinions.” They aligned with long-standing antisemitic narratives that have historically justified exclusion and violence. When a public figure with a global following makes such statements, the risk is not just that someone will be offended, but that such ideas are normalised, repeated, and even acted upon.

Hate speech, then, is best understood not as a matter of taste or manners, but as a mechanism of social harm. It constructs hierarchies between groups, licenses hostility, and marginalises those who are already vulnerable. And in digital spaces—where speech travels fast, reaches wide, and rarely disappears—its consequences are far from abstract.

2. Platform Governance: Between Host and Editor

2. Platform Governance: Between Host and Editor

Social media platforms often position themselves as neutral conduits for content, but in practice, they make active choices about what is visible, what is removed, and when to intervene. This ambiguous role sits at the core of ongoing debates around platform accountability, particularly in cases involving harmful or discriminatory speech.

Flew (2021) describes platforms as operating somewhere between passive hosts and active editors, holding considerable influence over what content circulates while denying editorial responsibility (p. 92). This tension creates a structural weakness in content governance: platforms are powerful enough to amplify harm, yet hesitant to take decisive action unless prompted by public outrage or reputational risk.

The case of Kanye West illustrates this failure. In October 2022, West published a series of antisemitic statements on Twitter and Instagram. Despite widespread condemnation, both platforms delayed action—Twitter left the posts online for several hours before restricting his account, while Instagram suspended him but allowed similar content to remain. These were not isolated incidents, but part of a pattern in which harmful speech by influential users is met with slow, uneven enforcement.

After Elon Musk acquired Twitter later that year, West’s account was reinstated, despite no evidence of remorse. It took another wave of inflammatory posts before any limitations were reimposed, raising concerns about inconsistent standards and politically motivated enforcement..

Such inconsistent responses reflect a broader trend: platform action often follows public backlash rather than policy. High-profile figures frequently benefit from leniency, and moderation decisions appear influenced by visibility, commercial interests, and public relations, rather than adherence to community guidelines.

3. Algorithmic Amplification: When Hate Gets Boosted

Even when platforms respond to hate speech, they often fail to address how their systems amplify it in the first place. The structure of social media is designed to reward engagement—likes, shares, comments, and views—regardless of the emotional or social impact of the content. As a result, harmful speech isn’t just hosted; it is prioritised.

Massanari (2017) argues that platform algorithms operate within what she calls a “toxic technoculture,” in which outrage, provocation, and polarisation are rewarded with greater visibility. Posts that stir strong emotional reactions—especially anger or fear—tend to spread faster, reach more users, and stay longer in public discourse. In this environment, hate speech isn’t just tolerated; it becomes profitable.

This dynamic was evident in the case of Kanye West. His controversial posts sparked a massive spike in online attention—his name trended globally, media coverage exploded, and millions engaged with the content across platforms. Even after his accounts were restricted, screenshots, reactions, and debates about his statements continued to circulate. The platform’s own infrastructure helped maximise the reach of the harm before any moderation occurred.

Recent data from the Pew Research Center (2021) supports this concern. Nearly 40% of American adults surveyed reported encountering hateful content on social media, with most believing that platforms do not do enough to curb it. This suggests a systemic issue: while content moderation may catch violations after they occur, the algorithmic design itself is part of the problem.

Platforms typically defend their algorithms as neutral tools responding to user preferences. But these systems are anything but neutral—they reflect embedded values and design choices that favour virality over safety. When celebrities or influencers post controversial material, their reach is automatically enhanced by engagement metrics. This means that their harmful messages are likely to be seen more, not less, simply because they generate attention.

In the context of hate speech, this is particularly dangerous. It creates a feedback loop where outrage feeds exposure, exposure fuels repetition, and repetition begins to normalise harm. Algorithms do not just passively reflect what people are talking about—they shape what people talk about. If platforms do not take algorithmic amplification seriously, efforts to regulate harmful content will always be one step behind.

4. Free Speech vs Harmful Speech: Rethinking Responsibility

Since the early days of the internet, platforms have positioned themselves as champions of free speech. In 1996, John Perry Barlow famously published the “Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” asserting that governments and institutions had no place in regulating online expression. His vision imagined the internet as a borderless, democratic space where speech would flow freely, unimpeded by authority or censorship (Barlow, 1996).

But the digital landscape today looks very different. Platforms like Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook are no longer fringe forums for open discourse—they are powerful gatekeepers of public communication, with billions of users and enormous influence over what voices are heard. When hate speech enters this environment, its effects can no longer be dismissed as part of the “marketplace of ideas.” In practice, certain voices are amplified, others are marginalised, and not all speech carries the same weight or consequence.

This imbalance becomes especially pronounced when the speaker is a celebrity or influencer. Public figures like Kanye West do not simply “post” on social media—they broadcast to massive audiences, often with global reach. Their words are not equal in impact to those of ordinary users. When they engage in hate speech, the harm is intensified, legitimised, and often echoed by their followers.

Yet platforms continue to invoke the rhetoric of “free speech” when defending inaction. This framing ignores the reality that some expressions inflict structural harm, particularly against marginalised communities. It also assumes a level playing field that does not exist. Free speech, in this context, becomes a shield—used to deflect responsibility rather than to promote open and respectful dialogue.

The challenge, then, is not to abandon free expression, but to distinguish between speech that contributes to democratic exchange and speech that undermines it. When expression perpetuates inequality, incites hatred, or threatens the safety of others, it ceases to be a neutral act. It becomes a form of violence—symbolic, social, and, at times, material.

Reconsidering the responsibilities of platforms and public figures is therefore crucial. Should highly influential users be held to a higher standard? Should platforms apply stricter pre-emptive moderation to accounts with large audiences? These are uncomfortable questions, but they are necessary ones if we are to create safer and more equitable digital spaces.

5. Conclusion: From Individual Words to Systemic Harm

Hate speech is not merely a matter of personal offence. As this blog has shown, it functions as a discursive tool of exclusion—reinforcing existing hierarchies and legitimising discrimination, particularly when voiced by powerful public figures. Understanding hate speech as structural harm shifts the conversation away from emotional sensitivity and toward meaningful accountability, both for individuals and for the platforms that enable them.

Cases like Kanye West’s do not exist in isolation. They reflect a broader pattern in which harmful speech, when delivered by high-profile users, is moderated inconsistently, amplified by algorithms, and often shielded by free speech rhetoric. Meanwhile, those targeted by such speech—Jewish communities in this case, but also women, LGBTQ+ people, racial minorities, and other marginalised groups—are left to bear the consequences in silence.

As digital platforms continue to shape public discourse, their responsibilities must evolve accordingly. Content governance can no longer rely on reactive, reputation-driven enforcement. It must include proactive strategies: transparent moderation policies, algorithmic accountability, and community-informed definitions of harm. Influential users should also be held to higher standards, recognising that their reach magnifies the social impact of their words.

At the same time, we as users must move beyond simplistic understandings of free speech. Protecting democratic exchange means confronting the ways in which language can harm—not just through intent, but through structure, repetition, and scale.

So what happens when hate speech is amplified by design, protected by influence, and delayed in moderation?

More importantly, what should we, as a society, demand in return?

Perhaps the first step is this: to stop asking whether platforms can intervene—and start asking why they so often choose not to.

References

Brison, S. J. (1998). The autonomy defense of free speech. Ethics, 108(2), 312–339. https://doi.org/10.1086/233807

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. Polity Press.

Langton, R. (2012). Beyond belief: Pragmatics in hate speech and pornography. In I. Maitra & M. K. McGowan (Eds.), Speech and harm: Controversies over free speech (pp. 72–93). Oxford University Press.

Maitra, I., & McGowan, M. K. (2012). Introduction. In I. Maitra & M. K. McGowan (Eds.), Speech and harm: Controversies over free speech (pp. 1–24). Oxford University Press.

Massanari, A. (2017). #Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures. New Media & Society, 19(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815608807

Parekh, B. (2012). Hate speech. In M. Herz & P. Molnar (Eds.), The content and context of hate speech: Rethinking regulation and responses (pp. 40–41). Cambridge University Press.

Hoffmann, M. (2022, November 7). Kanye West & antisemitism. Create OU. https://sites.create.ou.edu/madelinehoffmann/2022/11/07/kanye-west-antisemitism/

Reuters. (2022, October 11). Kanye West’s Twitter, Instagram accounts restricted after anti-Semitic posts. https://www.reuters.com/world/kanye-wests-twitter-instagram-accounts-restricted-after-alleged-anti-semitic-2022-10-09/

Allyn, B. (2022, October 25). Adidas cuts ties with Ye over antisemitic remarks that caused an uproar. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2022/10/25/1131285970/adidas-ye-kanye-west-antisemitic

Be the first to comment