Ghost in the machine: digital death in the age of algorithms

In February 2025, South Korean actress Kim Sae-ron committed suicide. Private photos and videos of her with male star Kim Soo-hyun appeared on social media one after another after her death. The private content triggered an angry public rebuke of Kim Soo-hyun in Asia, as well as sympathy and regret for Kim Sae-ron. This brings to light the harsh reality of privacy invasion in the context of the digital age. Moreover, this tragedy reveals a worrying truth: death does not end the possibility of privacy invasion. Death simply transfers control of our digital selves to corporations, relatives, and algorithms.

Figure1: After Kim Sae Ron’s death, Kim Soo Hyun faces controversy over alleged past relationship when she was a minor.(Chirag, April 4, 2025)

The story of Kim Sae-ron is not an uncommon one. Every day people leave this world for different reasons, leaving their digital footprint behind. Imagine who will take over those social media accounts full of memories, precious photos stored on cloud-based web drives, or important files locked in online accounts when we ourselves or someone we love passes away? Who decides what happens to them?

Figure2: Over 30 Million Facebook Accounts Belong to Dead Users, with Numbers Expected to Rise(famous.pulse, November 17, 2024)

Meta currently has over 30 million memorial accounts, a number that is so staggering (Öhman & Watson, 2019). Öhman and Watson(2019) predict that if Meta stops attracting new users, the platform could have more deceased users than living users by around 2070. Realistic and predictive data forces us to ponder the question: will we lose our digital privacy when we die?

The digital age has left us with a rich but worrying legacy. As we display and store more and more of our personal lives, information on digital platforms, the question of who inherits these digital legacies after we die becomes even more important to explore.

The issue is not simple. It involves legal, ethical and commercial interests. It exposes loopholes in the global legal framework and the dominance of tech companies in digital legacy decisions. In recent decades, science and technology have advanced faster than anyone could have imagined. And the law has often struggled to keep pace with it. The law currently lacks the relevant institutions and regulations when it comes to the emergence of a large number of deceased users and the associated digital privacy issues.

In this blog, I will look at the current challenges facing digital heritage, such as: legal deficiencies, ethical issues, and more. These factors will largely determine exactly how digital heritage should be controlled. And, I will also provide real-world case studies through which these dilemmas and challenges can be better understood. The goal of exploring this topic is to hopefully create a more robust, human-centered approach to digital heritage management.

What do we leave behind when we die? The value of digital legacy

Because we are so used to the digital age, we occasionally forget that digital has fundamentally changed the way we live and remember. At the same time, as this era continues to advance, it has brought with it the new concept of digital heritage. What is digital heritage? It refers to the vast amount of data and digital assets that we store in our networks. From social media profiles and emails to digital photos, videos, and even encrypted files, these all fall under the category of digital legacy. As we all know, these assets are rich in the emotions of their owners. At the same time, they also have considerable commercial value.

Figure3: https://cialisgf.com/digital-legacy-management-preserving-your-online-presence-for-the-future/

For families, digital legacies often hold particular emotional significance. Social media profiles become virtual memorials for the deceased, holding precious memories and giving loved ones the opportunity to connect with the deceased. Photos and videos in the cloud can provide some comfort in times of remembrance. In essence, digital legacy becomes an important link to the deceased, helping people to have an emotional outlet in times of need.

However, the value of digital legacies does not only exist in emotional terms. As Crawford (2021) argues that even the data of the deceased can have value. For tech companies, user data is a valuable asset that can be used for user behavior analysis, market trend prediction, and so on, which in turn can contribute to the development of their business models. This creates a paradox: on the one hand, families want to inherit the digital legacy of their loved ones; on the other hand, companies need to protect user privacy and maintain their business value.

What’s more, there is a big difference between different countries on how to deal with the issue of digital legacy. Some countries allow the inheritance of digital assets. Others, on the other hand, prohibit relatives from accessing the data of the deceased. Such differences complicate the issue, especially where international families are involved or where digital assets are stored in different jurisdictions.

The privacy paradox: who owns the data of the deceased?

The paradox between the right of privacy and the right of inheritance becomes acute when considering that it is the data of the deceased. This is because the line between ownership and control is blurred in this case.

Fogure4: “Right to be Forgotten” of GDPR (James, February 23, 2018)

At the heart of this contradiction lies the conflict between legal frameworks such as the GDPR and the policies of digital platforms. Article 17 of the GDPR, “Right to be Forgotten”, gives users the power to request the deletion of their personal data (Politou et al., 2018). However, the applicability of this provision to deceased users remains controversial. Karppinen (2017) points out that in the digital age, the ability to control personal information is seen as one of the new types of fundamental human rights, especially in the context of widespread data collection and processing. This raises the following questions: if living people have the right to decide how their data is used (informational self-determination), should this right also be respected and continued after death? And does the right to privacy extend beyond life?

These questions are compounded by the initiatives of some technology companies. While they offer users options on how to manage their accounts after death, such as Facebook’s Memorialization, Apple’s “Digital Legacy” program, and Google’s Inactive Account Manager, users still don’t have fully control the flow of their data. Besides, these initiatives do not fully address the complex needs of bereaved families. The current lack of well-established and standardized controls has left many users concerned about the insecurity of their digital information after they have passed away.

Digital platforms hold far more power than we realize. They can even determine the ultimate ownership of digital heritage. As Suzor (2019) puts it, platform rules have effectively taken on the role of law. These rules not only influence user behavior, but also determine the information that users can access. The power that digital platforms wield makes the need for greater accountability and transparency all the more urgent.

Case Study: Facebook Memorial Accounts and Family Inheritance Rights

The landmark Facebook inheritance case in Germany (2018, Federal Supreme Court ruling) is a vivid illustration of the complexity of digital legacy. The case involved a tragic accident and a family’s search for answers.

In 2012, a 15-year-old German girl died in a tragic accident at a Berlin subway station. The girl’s parents wanted to find out why she died and wondered if their daughter’s death was due to online violence. They asked Facebook for access to her account, but Facebook refused. The official reason given was that the user agreement clearly states that user data is not inheritable. They also stated that if the parents were allowed to access the deceased’s chat logs, the privacy of other users who had conversations with the deceased would be violated (Fuchs, 2021).

Through this case, we see the tension between the parents’ urgent desire to inherit their daughter’s digital assets and the platform’s obligation to protect users’ privacy. The girl’s family argued that a digital inheritance is the same as a physical inheritance. In their view, social media accounts are of the same nature as ordinary diaries or letters and should be treated equally. They emphasize that these digital assets contain emotional value and are important to them (Fuchs, 2021). However, Facebook still claims that social media accounts contain data about the deceased user’s interactions with other users and that they have a responsibility to protect their privacy. No one else has the right to access it without the consent of the user in question.

Ultimately, the German Federal Court of Justice (BGH) ruled that the family of the deceased could inherit the Facebook account and that the parents had the right to access the contents of their daughter’s account. The court held that the digital assets contained in a Facebook account are not fundamentally different from traditional forms of communication and should therefore be inherited in the same way as letters. This decision sets a precedent for the inheritance of digital assets in Germany.

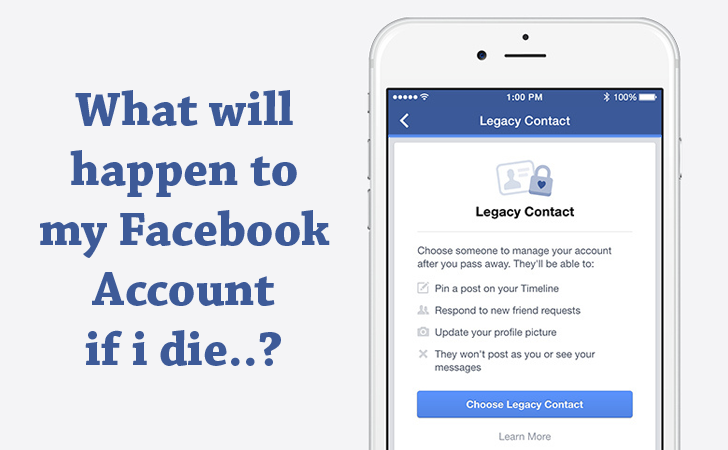

Figure5: Facebook’s Legacy Contact (Meta, February 12, 2015)

And then, in response to this judgment, Facebook introduced the “Legacy Contacts” feature. This feature allows users to choose to appoint someone else to manage their account after their death.

Taking back control: how to protect your digital legacy

With the previous discussion, you should have understood the complexities and challenges of digital legacy. Next, then, we need to discuss the solution, one that empowers individuals and protects their rights. Taking back control of your digital heritage requires a multi-faceted approach.

The individual level

At the individual level, one possible solution is to utilize Google’s “inactive account manager” tool. This feature allows users to create “digital wills” that specify what will happen to their data if the account is inactive for a certain period of time. For example, users can select 10 trustees that Google will notify once the account becomes inactive and allow them to access certain data (e.g., Gmail, Drive, photos, etc.) specified by the user. Alternatively, the user can choose to automatically delete the entire account and the data in it.The above approach allows us to take some control over our digital footprint and ensure that our digital legacy is organized the way we want it to be.

Long-term social and systemic change

However, individual action alone is not enough. At the governmental level, the relevant legislature can be urged to introduce legal provisions related to “data sovereignty”, explicitly granting users the right to decide the fate of their data, both before and after their death. In this way, the right to manage the digital heritage is handed over from the platform to the individual user, respecting the user’s due rights while protecting their privacy. At the enterprise level, tech companies need to provide more comprehensive and transparent programs for users to manage their digital legacy.

On an organizational level, international oversight committees independent of government businesses could be established. These committees would regulate businesses to prevent them from misusing private data and to protect the rights of the deceased and their families. In addition, we need a comprehensive international framework for the protection of digital rights. For example, international conventions related to digital human rights should be developed to establish globally applicable standards of judgment. In this way the digital heritage of individuals can be respected and protected globally.

The Data That Outlives Us

The length of life of our data selves is likely to exceed the length of our actual lives, and the duration of the rights we have should also exceed the length of our actual lives. The digital age has given us the opportunity to leave a large digital footprint. These digital footprints are more than just memories; they are collections of information and assets that have tremendous value.

Figure6: https://www.telegraphindia.com/science-tech/sorting-out-ones-digital-legacy-is-more-important-today-than-ever/cid/1847754

If you passed away today, would you wonder where your data would go? Who would have the right to manage that data? This remains an unanswered question.

In short, it is hoped that in the future, technology companies will empower users with the right to a “digital will”. Giving users the right to decide the fate of their digital legacy ensures that their wishes will be honored and that they will no longer have to worry about the security of their digital identity. Let’s shape a digital future where our rights extend beyond our lifetimes.

References:

Acronis. (2018, February 23). Backups and the GDPR right to be forgotten: What to expect? Acronis. Retrieved April 12, 2025, from https://www.acronis.com/en-sg/blog/posts/backups-and-gdpr-right-be-forgotten-what-expect/

Amazon. (n.d.). Digital legacy: Take control of your online afterlife [Kindle eBook]. Retrieved April 13, 2025, from https://www.amazon.com.au/Digital-Legacy-Take-Control-Afterlife-ebook/dp/B08NWHWHPG

Crawford, K. (2021). The atlas of AI: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press.

Cialisgf. (n.d.). Digital legacy management: Preserving your online presence for the future. Retrieved April 13, 2025, from https://cialisgf.com/digital-legacy-management-preserving-your-online-presence-for-the-future/

Fuchs, A. (2021, April). What happens to your social media account when you die? The first German judgments on digital legacy. ERA Forum, 22(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12027-021-00652-x

Famous Pulse. (2024, November 17). [Breakup post screenshot]. Instagram. Retrieved April 12, 2025, from https://www.instagram.com/famous.pulse/p/DCdr3hrJddA/

Karppinen, K. (2017). Human rights and the digital. In H. Tumber & S. Waisbord (Eds.), The Routledge companion to media and human rights (pp. 95–103). Routledge.

Meta. (2015, February 12). Adding a legacy contact. Meta Newsroom. https://about.fb.com/news/2015/02/adding-a-legacy-contact/

News18. (2025, April 4). Kim Sae Ron’s breakup message to Kim Soo Hyun goes viral: ‘It bothers me that…’. https://www.news18.com/movies/kim-sae-ron-breakup-message-to-kim-soo-hyun-goes-viral-it-bothers-me-that-ws-l-9286162.html

Öhman, C. J., & Watson, D. (2019). Are the dead taking over Facebook? A Big Data approach to the future of death online. Big Data & Society, 6(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951719842540

Politou, E., Michota, A., Alepis, E., Pocs, M., & Patsakis, C. (2018). Backups and the right to be forgotten in the GDPR: An uneasy relationship. Computer Law & Security Review, 34(6), 1247–1257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2018.08.006

Suzor, N. P. (2019). Lawless: The secret rules that govern our digital lives. Cambridge University Press.

Telegraph India. (2025, April 13). Sorting out one’s digital legacy is more important today than ever. https://www.telegraphindia.com/science-tech/sorting-out-ones-digital-legacy-is-more-important-today-than-ever/cid/1847754

Be the first to comment